That Which We Call Indica, by Any Other Name Would Smell As Sweet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cannabis Cultivation in the Ancient World (China)

5/23/2019 Cannabis Cultivation in the Ancient World (China) This diagram may be a simplification of the origins of cannabis domestication. Fossil pollen studies may be a better indication of where and when hemp cultivation originated. Cannabis Plant, Hemp Plants and Marijuana plants used Interchangeably. https://friendlyaussiebuds.com/cannabis-resources/education/blazes-throughout-the-ages-episode-i-getting-stoned-in-the-stone-age/ 1 5/23/2019 Approximately 2500 year old cannabis from The Yanghai Tombs in the Turpan Basin (Xinjiang Autonomous Region) of northwest China Approximately 1.7 lbs. of cannabis (A) was found to have characteristic marijuana trichomes (B and C) and a characteristic seed (D). This cannabis contained THC and was presumably employed by this culture as a medicinal or psychoactive agent, or an aid to divination (religious ritual). Ethan Russo et al. Journal of Experimental Botany, Volume 59, Issue 15, 1 November 2008, Pages 4171–4182 Archeological Excavations Yangshao hemp-cordmarked Amphora, Banpo Phase 4800 BCE, Shaanxi. Photographed at the Musee Guimet An amphora is used for storage, usually of liquids 2 5/23/2019 Discovery of Ancient Cannabis cloth Hemp Shoe from China ~ 100CE First hemp-weaved fabric in the World found wrapped around baby in 9,000-year-old house in Turkey The Scythians – the Greeks' name for this initially nomadic people – inhabited Scythia from at least the 11th century BC to the 2nd century AD. In the seventh century BC, the Scythians controlled large swaths of territory throughout Eurasia, from the Black Sea across Siberia to the borders of China. Herodotus[a] (484 BC – 425 BC) was an ancient Greek historian. -

Dispensary Selection Information

______________________________________________________________________________________ State of Vermont Department of Public Safety Marijuana Registry [phone] 802-241-5115 45 State Drive [fax] 802-241-5230 Waterbury, Vermont 05671-1300 [email] [email protected] www.medicalmarijuana.vermont.gov Dispensary Selection Information IMPORTANT INFORMATION CONTAINED BELOW WHEN COMPLETING THE FORMS TO REGISTER AS A PATIENT WITH THE VERMONT MARIJUANA REGISTRY (VMR). Materials provided by each dispensary are attached to assist patient applicants designating a dispensary. Registered patients may purchase marijuana, marijuana infused products, seeds, and clones from a registered dispensary. Registered patients who designate a dispensary may purchase marijuana products and cultivate marijuana in a single secure indoor facility. Registered patients who elect to cultivate marijuana in a single secure indoor facility must provide the address and location to the VMR on his or her application. Any updates to the address and/or location of the single secure indoor facility must be submitted in writing via email or mail to the contact information below. Registered patients may only purchase marijuana, marijuana infused products, seeds, and clones from one dispensary and must designate the dispensary of his or her choice on their application. Registered patients may only change dispensaries every 30 days. After 30 days, a registered patient may change his or her designated dispensary by submitting a completed Cardholder Information Notification form and a $25 processing fee. The VMR will issue the registered patient a new registry identification card with a new registry identification number. ALL registered patients and caregivers MUST schedule appointments prior to going to their designated dispensary to obtain marijuana, this includes seed and clones. -

Big-Catalogue-English-2020.Pdf

PAS CH SIO UT N D ® CATALOGUE English SEED COMPANY Feminized, autoflower and regular cannabis seeds AMSTERDAM, ESTABLISHED 1987 for recreational and medical use. Amsterdam - Maastricht YOUR PASSION OUR PASSION DUTCH PASSION 02 Contents Welcome to Dutch Passion Welcome to Dutch Passion 02 Dutch Passion was the second Cannabis Seed Company in the world, established in Amsterdam in 1987. It is our mission to supply Bestsellers 2019 02 the recreational and medical home grower with the highest quality cannabis products available in all countries where this is legally Regular, Feminized and Autoflower 03 allowed. Cannabinoids 03 Medical use of cannabis 03 After many years of dedication Dutch Passion remains a leading supplier of the world’s best cannabis genetics. Our experienced Super Sativa Seed Club 04 team do their utmost to maintain the quality of our existing varieties and constantly search for new ones from an extensive network Special Cannabinoids / THC-Victory 05 of worldwide sources. We supply thousands of retailers and seed distributors around the world. Dutch Outdoor 06 High Altitude 09 CBD Rich 10 Dutch Passion have never been afraid to upset conventional thinking; we invented feminized seeds in the 1990’s and more recently Latin America 13 have pioneered the introduction of 10-week Autoflower seeds which have helped make life even easier for the self-sufficient Classics 14 cannabis grower. CBD-rich medical cannabis genetics is a new area that we are proud to be leading. Skunk Family 19 Orange Family 21 The foundation of our success is the genetic control we have over our strains and the constant influx of new genetics that we obtain Blue Family 24 worldwide. -

A Multifaceted Approach to Address Variation in Cannabis Sativa

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 5-2019 A Multifaceted Approach to Address Variation in Cannabis Sativa Anna Louise Schwabe Follow this and additional works at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Schwabe, Anna Louise, "A Multifaceted Approach to Address Variation in Cannabis Sativa" (2019). Dissertations. 554. https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations/554 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2019 ANNA LOUISE SCHWABE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School A MULTIFACETED APPROACH TO ADDRESS VARIATION IN CANNABIS SATIVA A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anna Louise Schwabe College of Natural and Health Sciences School of Biological Sciences Biological Education May 2019 This Dissertation by: Anna Louise Schwabe Entitled: A Multifaceted Approach to Address Variation in Cannabis sativa has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in College of Natural and Health Sciences in School of Biological Sciences, Program of Biological Education. Accepted by the Doctoral Committee ____________________________________________________ -

Legalization of Cannabis in India

A Creative Connect International Publication 53 LEGALIZATION OF CANNABIS IN INDIA Written by Bhavya Bhasin 2nd year BALLB Student, Kirit P. Mehta School of Law, NMIMS ABSTRACT The underlying object of this research paper is to study and analyze why there is need to legalize cannabis in India. As it deals with the benefit that India will gain by legalizing cannabis as to how government would able to earn more revenue and would able to decrease the unemployment rate, how it would help in decreasing the crime rates in the country and it also explains the medical usage of cannabis. These aspects have been proven in research paper by comparing India with the other countries that have legalized cannabis. This research paper also deals with the current legal status of cannabis in India. ASIAN LAW & PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW ISSN 2581 6551 [VOLUME 3] DECEMBER 2018 A Creative Connect International Publication 54 INTRODUCTION Cannabis, commonly known as marijuana is a drug which is made up from Indian hemp plants like cannabis sativa and cannabis indica. The main active chemical in cannabis is Tetrahydrocannabinol(THC). Cannabis plant is used for medical purposes and recreational purposes. Cannabis is the plants that have played a vital role in the development of agriculture, which had great impact on both human beings and planet. Since many years cannabis has been used as medicinal drug, as an intoxicant and it has also been used in some religious rituals. The Hindu God Shiva is the lord of the bhang as in ‘Mahashivratri’ there is Prasad mixed with bhang and it still plays a very symbolic role in the religious practices of Hindus. -

The Official High Times Cannabis Cookbook: More Than 50 Irresistible Recipes That Will Get You High

CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INTRODUCTION TO CANNABIS COOKERY CHAPTER 1: Active Ingredients Basic Recipes THC Oil (Cannabis-Infused Oil) Cannacoconut Oil Cannabis-Infused Mayonnaise Simple Cannabutter Long-Simmering Cannabutter Wamm Marijuana Flour Tinctures Quick Cannabis Glycerite Long-Simmering Ganja Glycerin Green Avenger Cannabis Tincture CHAPTER 2: Irie Appetizers Roasted Ganja Garlic Cannellini Dip Hookah Lounge Hummus Green Leafy Kale Salad in Brown Cannabutter Vinaigrette Obama’S Sativa Samosas Stuffed Stoned JalapeñO Poppers Sativa Shrimp Spring Rolls with Mango Sauce Ganja Guacamole Mini Kind Veggie Burritos Pico de Ganja and Nachos Kind Bud Bruschetta with Pot Pesto Stoner Celebrity Favorite: Lil’ Snoop Hot Doggy Doggs CHAPTER 3: Munchie Meals Reggae Rice and Bean Soup Cream of Sinsemilla Soup Tom Yum Ganja Stoner Celebrity Favorite: Texas Cannabis Chili Shroomin’ Broccoli Casserole Om Circle Stuffed Butternut Squash Chicken and Andouille Ganja Gumbo Time-Warp Tamales Red, Green, and Gold Rasta Pasta Potato Gnocchi with Wild Mushroom Ragu Big Easy Eggplant Alfredo Ganja Granny’s Smoked Mac ‘n’ Cheese Psychedelic Spanakopita Sour Diesel Pot Pie Cheeto Fried Chicken Bacon-Wrapped Pork Tenderloin with Mango Chipotle Glaze Pot-and-Pancetta-Stuffed Beef Tenderloin with Port Mushrooms CHAPTER 4: High Holidays Valentine’s Day, February 14: Sexy Ganja–Dipped Strawberries St. Patrick’s Day, March 17: Green Ganja Garlic Smashed Potatoes 4/20, Cannabis Day, April 20: 420 Farmers’ Market Risotto Independence Day, July 4: Sweet and Tangy Bar–B–Cannabis -

An Ayurvedic Approach to the Use of Cannabis to Treat Anxiety By: Danielle Bertoia at (Approximately) Nearly 5000 Years Old, Ay

An Ayurvedic Approach to the use of Cannabis to treat Anxiety By: Danielle Bertoia At (approximately) nearly 5000 years old, Ayurveda is touted as being one of, if not the oldest healing modality on the planet. The word Ayurveda translates from Sanskrit to “The Science of Life” and is based on the theory that each of us are a unique blend of the 5 elements that make up the known Universe and our planet. Earth, air, fire, water and ether all combine together to create our physical form. When living in harmony with the rhythms of nature and in accordance to our unique constitution, health prevails. When we step outside of our nature by eating foods that are not appropriate, exposing ourselves to outside stressors, and by ignoring the power of our internal knowing, we then leave ourselves vulnerable to dis-ease. Doshic theory reveals to us that these 5 elements then combine with one another to create 3 Doshas. Air and Ether come together to create Vata, Fire and Water to create Pitta and Earth and Water to create Kapha. As we take our first breath upon birth, we settle into our Primary, Secondary and Tertiary doshas, also known as our Prakruti. This becomes our initial blueprint, our Health Touchstone if you will, which we will spend our lifetimes endeavoring to preserve. As time and experience march on, we may begin to experience a distancing from this initial blueprint, a disconnect from our true health, also known as our Vikruti. Outside stress, incorrect food choices, our personal karma and incorrect seasonal diet can all contribute to an imbalanced state within the doshas. -

Cannabis in the Ancient World Chris Bennet

Cannabis in the Ancient World Chris Bennet The role of cannabis in the ancient world was manifold, a food, fiber, medicine and as a magically empowered religious sacrament. In this paper the focus will be on archaic references to cannabis use as both a medicine and a sacrament, rather than as a source of food or fiber, and it’s role in a variety of Ancient cultures in this context will be examined. Unfortunately, due to the deterioration of plant matter archeological evidence is sparse and “Pollen records are frequently unreliable, due to the difficulty in distinguishing between hemp and hop pollen” (Scott, Alekseev, Zaitseva, 2004). Despite these difficulties in identification some remains of cannabis fiber, cannabis beverages utensils, seeds of cannabis and burnt cannabis have been located (burnt cannabis has been carbonized and this preserves identifiable fragments of the species). Fortunately other avenues of research regarding the ancient use of cannabis remain open, and etymological evidence regarding cannabis use in a number of cultures has been widely recognized and accepted. After nearly a lifetime of research into the role of psychoactive plants in human history the late Harvard University Professor of ethnobotany, Richard Evans Schultes commented: "Early man experimented with all plant materials that he could chew and could not have avoided discovering the properties of cannabis (marijuana), for in his quest for seeds and oil, he certainly ate the sticky tops of the plant. Upon eating hemp, the euphoric, ecstatic and hallucinatory aspects may have introduced man to the other-worldly plane from which emerged religious beliefs, perhaps even the concept of deity. -

ARMENIA: COUNTRY REPORT to the FAO INTERNATIONAL TECHNICAL CONFERENCE on PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES (Leipzig,1996)

ARMENIA: COUNTRY REPORT TO THE FAO INTERNATIONAL TECHNICAL CONFERENCE ON PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES (Leipzig,1996) Prepared by: Ministry of Agriculture Yerevan, June 1995 ARMENIA country report 2 Note by FAO This Country Report has been prepared by the national authorities in the context of the preparatory process for the FAO International Technical Conference on Plant Genetic Resources, Leipzig, Germany, 17-23 June 1996. The Report is being made available by FAO as requested by the International Technical Conference. However, the report is solely the responsibility of the national authorities. The information in this report has not been verified by FAO, and the opinions expressed do not necessarily represent the views or policy of FAO. The designations employed and the presentation of the material and maps in this document do not imply the expression of any option whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ARMENIA country report 3 Table of contents CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE REPUBLIC OF ARMENIA AND ITS AGRICULTURAL SECTOR 4 1.1 MAJOR TYPES OF FORESTS 6 1.2 AGRICULTURAL SECTOR 6 CHAPTER 2 INDIGENOUS PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES 8 2.1 FOREST GENETIC RESOURCES 8 2.2 CEREALS 10 2.3 GRAIN LEGUMES 12 2.4 FORAGE GRASSES 12 2.5 FRUIT AND BERRY PLANTS 13 2.6 VEGETABLES AND MELONS 14 2.7 WILD EDIBLE PLANTS 14 CHAPTER 3 NATIONAL EFFORTS IN PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES CONSERVATION -

Medicinal Cannabis Samples

המחקר של השוני הכימי של חשיש ממקורות שונים שנתפס בישראל לומיר הנוש המכון למדעי התרופה בית הספר לרוקחות 2014 1 The study of chemical differences of hashish from different sources seized in Israel. Lumír Hanuš Institute for Drug Research School of Pharmacy 2014 2 תקציר קנאביס, בצורת הצמח והשרף, הוא הסם הפופולרי ביותר בישראל בשנים האחרונות. עד 5002, היו המקורות העיקריים של שרף הקנביס )הידוע גם כחשיש( בשוק הסמים הישראלי לבנון והודו. החשיש ממקורות אלה יכול להיות מובחן על ידי המראה החיצוני שלו. מטרת מחקר זה הייתה לבדוק האם יש הבדל באיכות החשיש מכל מקור .לצורך כך, כימתנו את הקנבינואידים הראשיים, קנבידיול )CBD(, תתרהידרוקנבינול )THC( וקנבינול )CBN( של חשיש שנתפס בתפיסות משטרה ממקורות ידועים - לבנון, הודו ומרוקו, שהועברו למעבדה לכימיה אנליטית של המחלקה לזיהוי פלילי במטה הארצי של משטרת ישראל, ולאחר מכן לאוניברסיטה העברית לאנליזה כמותית. התוצאות, המבוססות על תפיסות רבות ושונות, הראו כי CBD של חשיש מלבנון השתנה מ26.5%- ל95625%- )ממוצע של THC , )8658 ± 0625% של חשיש מלבנון השתנה מ0650%- ל0650%- )ממוצע של 0652% ± 5608) , CBD של חשיש ממרוקו השתנה מ9625%- ל2690%- )ממוצע של THC ,)0625 ± 0695% של חשיש ממרוקו השתנה מ2608%- ל90609%- )ממוצע של CBD ,)5659 ± 0600% של חשיש מהודו השתנה מ0628%- ל- 90690% )ממוצע של % 9602 ± 0625(, ו-THC של חשיש מהודו השתנה מ0620%- ל9.602%- )ממוצע של .(.602 ± 9620% באותו זמן, זוהו כמה קנבינואידים אחרים, שנמצאו בדגימות בכמות נמוכה יותר )זוהו - cannabidivarol , CBDV 9-tetrahydrocannabivarol - 9-THCV , cannabivarol - CBV , cannabichromene - CBC , monomethyl cannabigerol - CBGM , 8- tetrahydrocannabinol - 8 -THC , cannabielsoin - CBE ו- cannabigerol – CBG( . הדגימות, בעיקר מלבנון, מרוקו והודו, הוערכו לפנוטיפ הכימי )סוג תרופה וסוג סיבים( במטרה לקבוע את המקור הגיאוגרפי של דגימות אלה. -

Edible Marijuana: a New Frontier in the Culinary World Ariella H

Johnson & Wales University ScholarsArchive@JWU Honors Theses - Providence Campus College of Arts & Sciences Fall 2012 Edible Marijuana: A New Frontier in the Culinary World Ariella H. Wolkowicz Johnson & Wales University - Providence, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.jwu.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Alternative and Complementary Medicine Commons, Arts and Humanities Commons, Chemicals and Drugs Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Repository Citation Wolkowicz, Ariella H., "Edible Marijuana: A New Frontier in the Culinary World" (2012). Honors Theses - Providence Campus. 8. https://scholarsarchive.jwu.edu/student_scholarship/8 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ScholarsArchive@JWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses - Providence Campus by an authorized administrator of ScholarsArchive@JWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Edible Marijuana: A New Frontier in the Culinary World Ariella Wolkowicz Johnson & Wales University-Providence Dr. Scott Smith, Dr. Cheryl Almeida Fall 2012 Wolkowicz 2 Abstract Cannabis, commonly known as marijuana, has a rich history as a source of fiber, food and medicine (Li 437). Since 1785, physicians and scientists alike have worked to discover the active chemical components and medical effectiveness of this plant (Touw 2; Aldrich). Despite its complicated legal history, marijuana has retained a place culturally and, in some countries, scientifically as an effective medical agent. As a medically edible ingredient, cannabis has also been more recently heralded as a new, even cutting edge flavor, opening a new frontier to the culinary community. -

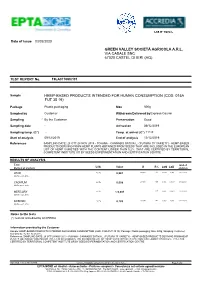

Hemp-Based Products Intended for Human Consumption (Cod

LAB N°0282 L Date of issue 03/02/2020 GREEN VALLEY SOCIETÀ AGRICOLA A.R.L. VIA CASALE SNC 67020 CASTEL DI IERI (AQ) TEST REPORT No. 19LA0110807/01 Sample HEMP-BASED PRODUCTS INTENDED FOR HUMAN CONSUMPTION (COD. 015A FUT 35 19) Package Plastic packaging Size 500g Sampled by Customer Withdrawn/Delivered byExpress Courier Sampling * By the Customer Preservation Good Sampling date - Arrived on 06/12/2019 Sampling temp. (C°) - Temp. at arrival (C°) +11.0 Start of analysis 09/12/2019 End of analysis 13/12/2019 References SAMPLING DATE: 28 OTT-28 NOV 2019 - POJANA - CANNABIS SATIVA L. ('FUTURA 75' VARIETY) - HEMP-BASED PRODUCTS DERIVING FROM HEMP PLANTS OBTAINED FROM SEEDS THAT ARE INCLUDED IN THE EUROPEAN LIST OF HEMP VARIETIES WITH THC CONTENT LOWER THAN 0,2%, THAT ARE CERTIFIED BY TERRITORIAL COMPETENT INSTITUTE OR BY SEEDS EXPERIMENTATION AND CERTIFICATION CENTRE RESULTS OF ANALYSIS Test End of Method of analysis U.M. Value U R% LoQ LoD analysis LEAD mg/Kg 0,661 ±0,066 99 0,010 0,005 13/12/2019 MI 979 rev 21 2019 CADMIUM mg/Kg 0,008 ±0,001 109 0,001 0,0005 13/12/2019 MI 979 rev 21 2019 MERCURY mg/Kg < 0,001 117 0,001 0,0003 13/12/2019 MI 979 rev 21 2019 ARSENIC mg/Kg 0,188 ±0,019 90 0,005 0,003 13/12/2019 MI 979 rev 21 2019 Notes to the tests (*): test not accredited by ACCREDIA Information provided by the Customer Sample: HEMP-BASED PRODUCTS INTENDED FOR HUMAN CONSUMPTION (COD.