The USDA Forest Service— the First Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Summer 2019

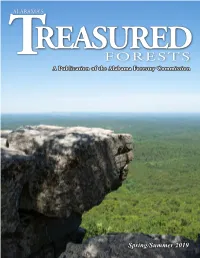

ALABAMA’S REASURED T FORESTS A Publication of the Alabama Forestry Commission Spring/Summer 2019 Message from the GOVERNOR STATE FORESTER Kay Ivey ALABAMA FORESTRY COMMISSION n my letter for this magazine, I want to take a different Katrenia Kier, Chairman approach than I normally do. A little-known responsibili- Robert N. Turner, Vice Chair ty of the Alabama Forestry Commission is helping the Robert P. Sharp state in times of disaster. Sure, when a tornado, hurricane, Stephen W. May III Ior ice storm hits, we are on the scene with chainsaws and Jane T. Russell equipment to clear the roads, but we offer much more than Dr. Bill Sudduth Joseph Twardy that. Through our training to fight wildfires, we have an inci- dent management team ready at all times to serve the state. I STATE FORESTER want to take this opportunity to brag on the men and women Rick Oates who make up this team and agency. As everyone knows, on March 3rd a series of tornadoes Rick Oates, State Forester ASSISTANT STATE FORESTER devastated parts of Lee County. Twenty-three people were Bruce Springer killed, and the homes of many more were destroyed. It was total devastation in parts of the county. As is often the case, the Alabama Forestry Commission was FOREST MANAGEMENT DIVISION DIRECTOR called in to assist the citizens of Lee County. Through this effort, my eyes were Will Brantley opened to the true capabilities of the Alabama Forestry Commission. PROTECTION DIVISION DIRECTOR Our team, led by James “Moto” Williams, jumped into action and took over John Goff the coordination of volunteers; at first in Smiths Station, and later in Beauregard. -

Lakes Basin Bibliography

Lakes Basin Bibliography OREGON STATE UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES Lakes Basin Bibliography Bonnie E. Avery 4/2/2010 The Lakes Basin Bibliography consists of over 600 references relating to the natural resources of Oregon‘s Lakes Basin. Forty percent of the items listed are available to anyone online though not all links are persistent. The remaining sixty percent are held in at least one library either in print or via subscriptions to e-journal content. This set is organized in groups related issues associated with digitization and contribution to an institutional repository such as the ScholarsArchive@OSU which provide for persistent URLs. Also identified are ―key‖ documents as identified by Lakes Basin Explorer project partners and topical websites. i Lakes Basin Bibliography Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 I-a: Resources available online: Documents .............................................................................. 2 I-b: Resources available online: Streaming Video .................................................................... 30 II-a. Candidates for digitization: Print-only OSU Theses and Dissertations ............................. 33 II-b. Candidates for digitization: Government and other reports ............................................... 39 II-c: Candidates for digitization: Local archive collections ........................................................ 53 II-d. Candidates for digitization: Maps -

Health Guidelines Vegetation Fire Events

HEALTH GUIDELINES FOR VEGETATION FIRE EVENTS Background papers Edited by Kee-Tai Goh Dietrich Schwela Johann G. Goldammer Orman Simpson © World Health Organization, 1999 CONTENTS Preface and acknowledgements Early warning systems for the prediction of an appropriate response to wildfires and related environmental hazards by J.G. Goldammer Smoke from wildland fires, by D E Ward Analytical methods for monitoring smokes and aerosols from forest fires: Review, summary and interpretation of use of data by health agencies in emergency response planning, by W B Grant The role of the atmosphere in fire occurrence and the dispersion of fire products, by M Garstang Forest fire emissions dispersion modelling for emergency response planning: determination of critical model inputs and processes, by N J Tapper and G D Hess Approaches to monitoring of air pollutants and evaluation of health impacts produced by biomass burning, by J P Pinto and L D Grant Health impacts of biomass air pollution, by M Brauer A review of factors affecting the human health impacts of air pollutants from forest fires, by J Malilay Guidance on methodology for assessment of forest fire induced health effects, by D M Mannino Gaseous and particulate emissions released to the atmosphere from vegetation fires, by J S Levine Basic fact-determining downwind exposures and their associated health effects, assessment of health effects in practice: a case study in the 1997 forest fires in Indonesia, by O Kunii Smoke episodes and assessment of health impacts related to haze from forest -

George M. Leader, 1918-2013 Michael J

Gettysburg College Faculty Books 2014 George M. Leader, 1918-2013 Michael J. Birkner Gettysburg College Charles H. Glatfelter Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/books Part of the Cultural History Commons, Oral History Commons, Public History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Birkner, Michael J. and Charles H. Glatfelter. George M. Leader, 1918-2013. Musselman Library, 2014. Second Edition. This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/books/78 This open access book is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. George M. Leader, 1918-2013 Description George M. Leader (1918-2013), a native of York, Pennsylvania, rose from the anonymous status of chicken farmer's son and Gettysburg College undergraduate to become, first a State Senator, and then the 36th governor of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. A steadfast liberal in a traditionally conservative state, Leader spent his brief time in the governor's office (1955-1959) fighting uphill battles and blazing courageous trails. He overhauled the state's corrupt patronage system; streamlined and humanized its mental health apparatus; and, when a black family moved into the white enclave of Levittown, took a brave stand in favor of integration. -

IMBCR Report

Integrated Monitoring in Bird Conservation Regions (IMBCR): 2015 Field Season Report June 2016 Bird Conservancy of the Rockies 14500 Lark Bunting Lane Brighton, CO 80603 303-659-4348 www.birdconservancy.org Tech. Report # SC-IMBCR-06 Bird Conservancy of the Rockies Connecting people, birds and land Mission: Conserving birds and their habitats through science, education and land stewardship Vision: Native bird populations are sustained in healthy ecosystems Bird Conservancy of the Rockies conserves birds and their habitats through an integrated approach of science, education and land stewardship. Our work radiates from the Rockies to the Great Plains, Mexico and beyond. Our mission is advanced through sound science, achieved through empowering people, realized through stewardship and sustained through partnerships. Together, we are improving native bird populations, the land and the lives of people. Core Values: 1. Science provides the foundation for effective bird conservation. 2. Education is critical to the success of bird conservation. 3. Stewardship of birds and their habitats is a shared responsibility. Goals: 1. Guide conservation action where it is needed most by conducting scientifically rigorous monitoring and research on birds and their habitats within the context of their full annual cycle. 2. Inspire conservation action in people by developing relationships through community outreach and science-based, experiential education programs. 3. Contribute to bird population viability and help sustain working lands by partnering with landowners and managers to enhance wildlife habitat. 4. Promote conservation and inform land management decisions by disseminating scientific knowledge and developing tools and recommendations. Suggested Citation: White, C. M., M. F. McLaren, N. J. -

Municipal Pension Reporting Program (Formerly Perc) Harrisburg 17120

March 2021 A Summary of 2018 Municipal Pension Plan Data Based on the January 1, 2019, Actuarial Valuation Reports Submitted Pursuant to Act 205 of 1984 & 2017 County Pension Plan Data Based on the January 1, 2018, Actuarial Valuation Reports Submitted Pursuant to Act 293 of 1972 COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA MUNICIPAL PENSION REPORTING PROGRAM (FORMERLY PERC) HARRISBURG 17120 March 2021 Members of the Pennsylvania General Assembly and Governor Wolf: Pursuant to Act 100 of 2016, the Department of the Auditor General took over responsibility for collection and biennial reporting of the commonwealth’s municipal pension plans status. I am pleased to submit the Municipal Pension Reporting Program’s (formerly the Public Employee Retirement Commission) biennial report on the status of the commonwealth’s local government pension plans for your review and information. Similar to prior years, my department will be providing additional analysis of this data in early 2021. Pennsylvania’s pension plans for local government employees in total represent one of the largest retirement systems in the nation. Currently, there are more than 3,300 local government pension plans in Pennsylvania and the number continues to grow. Unfortunately, the struggle to properly fund the plans also continues to grow. Many municipalities face financial hardships as well as the reality of more retired members drawing from pension plans than active members contributing to the plans. This status report provides a snapshot of the condition of local government pension plans throughout the commonwealth. Reported data shows that 98 percent of the pension plans in Pennsylvania are considered small (fewer than 100 members). -

Lincoln National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan September 1986 Table of Contents

Lincoln National Forest Land and Resource Management Plan September 1986 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION Page Purpose of the Plan 1 Organization of the Proposed Forest Plan Document 2 2. PUBLIC ISSUES AND MANAGEMENT CONCERNS Overview 3 Issues 3 Dispersed, Cave and Developed Recreation 3 Wilderness 4 Range 4 Timber 5 Fuelwood 5 Minerals 6 Lands 6 Fire 6 Insects and Diseases 6 Law Enforcement 6 Transportation 6 Local Residents and Regional Users 7 3. SUMMARY OF THE ANALYSIS OF THE MANAGEMENT SITUATION Overview 9 4. MANAGEMENT DIRECTION Mission 11 Goals 1l Timber 1l Wilderness 1l Wildlife and Fish 1l Range 12 Recreation 12 Minerals 12 Water and Soils 12 Human and Community Development 13 Lands 13 Facilities 13 Protection 13 Objectives 14 Management Prescriptions 25 Management Area Description 25 Management Description 25 Activities 25 Standards and Guidelines 25 How to Apply the Prescriptions 26 Management Prescriptions 28 5. MONITORING PLAN Introduction 155 Timber 1- Acres of Regeneration Harvest 156 Timber 2- Acres of Intermediate Harvest 156 Timber 3- Adequate Restocking of Regeneration Harvests and Other Reforestation Projects 157 Timber 4- Timber Stand Improvement Acres 157 Timber 5- Board Feet of Net Sawtimber Offered 157 Timber 6- Size Limits for Harvest Areas 158 Timber 7- Re-evaluation of Unsuitable Timber Lands 158 Timber 8- Cords of Fuelwood Made Available 159 Range 1- Acres of Overstory Modification in Woodland Type 159 Range 2- Acres of Brush Conservation and/or Reseeding 159 Range 3- Range Development 160 Range 4- Permitted -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1972 HON. RON PAUL HON. THOMAS G. TANCREDO HON. DANNY K. DAVIS HON. MICHAEL N. CA

E1972 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks September 29, 2006 and values. Not those of the enemy. In the PAYING TRIBUTE TO LAURA Diabetes Research Foundation Galas, Chil- meantime, if we continue to defile our inter- LONDONO dren’s Congress, Walk for a Cure, the fight for national agreements by blatantly disregarding stem cell research and many others. She has them, it will only mean our profile abroad will HON. THOMAS G. TANCREDO told me her stories of low and high blood sug- continue to suffer, potentially to the great det- OF COLORADO ars, she has shown me how she pricks her riment of our men and women in uniform, and IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES fingers and takes her insulin and she has al- ultimately to our goal of successfully defeating ways demonstrated a positive attitude through our enemy. Friday, September 29, 2006 it all. I would ask my colleagues, and I would ask Mr. TANCREDO. Mr. Speaker, I rise today Most of all, I am proud to call her my friend. the American people, do we really believe that to pay tribute to one of my constituents, Ms. Recently, we shared the podium at an event we must betray our moral standard in order to Laura Londono of Highlands Ranch, Colorado. at Alfred I. DuPont Hospital for Children, and defeat our enemies? We are fighting a dif- Ms. Londono has been accepted to the Peo- it is safe to say that Allie stole the show! Allie ferent enemy, one espousing a radical ide- ple to People World Leadership Forum here in is surrounded by loving parents and two won- ology and using blatant violence as a vehicle our Nation’s Capital. -

The Teacher and the Forest: the Pennsylvania Forestry Association, George Perkins Marsh, and the Origins of Conservation Education

The Teacher and The ForesT: The Pennsylvania ForesTry associaTion, GeorGe Perkins Marsh, and The oriGins oF conservaTion educaTion Peter Linehan ennsylvania was named for its vast forests, which included well-stocked hardwood and softwood stands. This abundant Presource supported a large sawmill industry, provided hemlock bark for the tanning industry, and produced many rotations of small timber for charcoal for an extensive iron-smelting industry. By the 1880s, the condition of Pennsylvania’s forests was indeed grim. In the 1895 report of the legislatively cre- ated Forestry Commission, Dr. Joseph T. Rothrock described a multicounty area in northeast Pennsylvania where 970 square miles had become “waste areas” or “stripped lands.” Rothrock reported furthermore that similar conditions prevailed further west in north-central Pennsylvania.1 In a subsequent report for the newly created Division of Forestry, Rothrock reported that by 1896 nearly 180,000 acres of forest had been destroyed by fire for an estimated loss of $557,000, an immense sum in those days.2 Deforestation was also blamed for contributing to the pennsylvania history: a journal of mid-atlantic studies, vol. 79, no. 4, 2012. Copyright © 2012 The Pennsylvania Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.118.152.206 on Wed, 14 Mar 2018 16:19:01 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms PAH 79.4_16_Linehan.indd 520 26/09/12 12:51 PM the teacher and the forest number and severity of damaging floods. Rothrock reported that eight hard-hit counties paid more than $665,000 to repair bridges damaged from flooding in the preceding four years.3 At that time, Pennsylvania had few effective methods to encourage forest conservation. -

Table of Contents

TABLEGUIDELINES OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 12: CONTACT INFORMATION AND MAPS 12.1 ADOT CONTACT INFORMATION……………………………………………….......122 12.2 BLM CONTACT INFORMATION…………………………………………………......123 12.3 USFS CONTACT INFORMATION………………………………………………….....124 12.4 FHWA CONTACT INFORMATION…………………………………………………....130 12.5 GIS INFORMATION..............................................................................................131 12.6 MAPS...................................................................................................................132 121 12.1 ADOT CONTACT INFORMATION ADOT web link azdot.gov/ ADOT maps azdot.gov/maps General Information 602-712-7355 OFFICE ADOT DIRECTOR 602.712.7227 Deputy Director of Transportation 602.712.7391 Deputy Director of Policy 602.712.7550 Deputy Director of Business Operations 602.712.7228 Multimodal Planning Division (MPD) Director 602.712.7431 MPD Planning and Programming Director 602.712.8140 MPD Planning and Environmental Linkages Manager 602.712.4574 Infrastructure Delivery and Operations Division (IDO) 602.712.7391 State Engineer, Sr. Deputy State Engineer and Deputy State Engineer Offices 602.712.7391 DISTRICT ENGINEERS Northcentral azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/northcentral 928.774.1491 Northeast azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/northeast 928.524.5400 Central Construction District azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/central 602.712.8965 Central Maintenance District azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/central 602.712.6664 Northwest azdot.gov/business/district-contacts/northwest 928.777.5861 -

National Monuments and the Forest Service

NATIONAL MONUMENTS AND THE FOREST SERVICE Gerald W. Williams, Ph.D., (Retired) USDA Forest Service Washington, DC National monuments are areas of federal land set aside by the Congress or most often by the president, under authority of the American Antiquities Act of June 8, 1906, to protect or enhance prominent or important features of the national landscape. Such important national features include those land areas that have historic cultural importance (sites and landmarks), prehistoric prominence, or those of scientific or ecological significance. Today, depending on how one counts, there are 81 national monuments administered by the USDI National Park Service, 13 more administered by the USDI Bureau of Land Management (BLM), five others administered by the USDA Forest Service, two jointly managed by the BLM and the National Park Service, one jointly administered by the BLM and the Forest Service, one by the USDI Fish & Wildlife Service, and another by the Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home in Washington, D.C. In addition, one national monument is under National Park Service jurisdiction, but managed by the Forest Service while another is on USDI Bureau of Reclamation administered land, but managed by the Park Service. The story of the national monuments and the Forest Service also needs to cover briefly the creation of national parks from national forest and BLM lands. More new national monuments and national parks are under consideration for establishment. ANTIQUITIES ACT OF 1906 Shortly after the turn of the century, many citizens’ groups and organizations, as well as members of Congress, believed it was necessary that an act of Congress be passed to combat the increasing acts of vandalism and even destruction of important cultural (historic and prehistoric), scenic, physical, animal, and plant areas around the country (Rothman 1989). -

A Bill to Designate Certain National Forest System Lands in the State of Oregon for Inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System and for Other Purposes

97 H.R.7340 Title: A bill to designate certain National Forest System lands in the State of Oregon for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System and for other purposes. Sponsor: Rep Weaver, James H. [OR-4] (introduced 12/1/1982) Cosponsors (2) Latest Major Action: 12/15/1982 Failed of passage/not agreed to in House. Status: Failed to Receive 2/3's Vote to Suspend and Pass by Yea-Nay Vote: 247 - 141 (Record Vote No: 454). SUMMARY AS OF: 12/9/1982--Reported to House amended, Part I. (There is 1 other summary) (Reported to House from the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs with amendment, H.Rept. 97-951 (Part I)) Oregon Wilderness Act of 1982 - Designates as components of the National Wilderness Preservation System the following lands in the State of Oregon: (1) the Columbia Gorge Wilderness in the Mount Hood National Forest; (2) the Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness in the Mount Hood National Forest; (3) the Badger Creek Wilderness in the Mount Hood National Forest; (4) the Hidden Wilderness in the Mount Hood and Willamette National Forests; (5) the Middle Santiam Wilderness in the Willamette National Forest; (6) the Rock Creek Wilderness in the Siuslaw National Forest; (7) the Cummins Creek Wilderness in the Siuslaw National Forest; (8) the Boulder Creek Wilderness in the Umpqua National Forest; (9) the Rogue-Umpqua Divide Wilderness in the Umpqua and Rogue River National Forests; (10) the Grassy Knob Wilderness in and adjacent to the Siskiyou National Forest; (11) the Red Buttes Wilderness in and adjacent to the Siskiyou