Walking the Talk: Reflections on Indigenous Media Audience Research Methods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 26, 2014 (Series 29: 1) D.W

August 26, 2014 (Series 29: 1) D.W. Griffith, BROKEN BLOSSOMS, OR THE YELLOW MAN AND THE GIRL (1919, 90 minutes) Directed, written and produced by D.W. Griffith Based on a story by Thomas Burke Cinematography by G.W. Bitzer Film Editing by James Smith Lillian Gish ... Lucy - The Girl Richard Barthelmess ... The Yellow Man Donald Crisp ... Battling Burrows D.W. Griffith (director) (b. David Llewelyn Wark Griffith, January 22, 1875 in LaGrange, Kentucky—d. July 23, 1948 (age 73) in Hollywood, Los Angeles, California) won an Honorary Academy Award in 1936. He has 520 director credits, the first of which was a short, The Adventures of Dollie, in 1908, and the last of which was The Struggle in 1931. Some of his other films are 1930 Abraham Lincoln, 1929 Lady of the Pavements, 1928 The Battle of the Sexes, 1928 Drums of Love, 1926 The Sorrows of Satan, 1925 That Royle Girl, 1925 Sally of the Sawdust, 1924 Darkened Vales (Short), 1911 The Squaw's Love (Short), 1911 Isn't Life Wonderful, 1924 America, 1923 The White Rose, 1921 Bobby, the Coward (Short), 1911 The Primal Call (Short), 1911 Orphans of the Storm, 1920 Way Down East, 1920 The Love Enoch Arden: Part II (Short), and 1911 Enoch Arden: Part I Flower, 1920 The Idol Dancer, 1919 The Greatest Question, (Short). 1919 Scarlet Days, 1919 The Mother and the Law, 1919 The Fall In 1908, his first year as a director, he did 49 films, of Babylon, 1919 Broken Blossoms or The Yellow Man and the some of which were 1908 The Feud and the Turkey (Short), 1908 Girl, 1918 The Greatest Thing in Life, 1918 Hearts of the World, A Woman's Way (Short), 1908 The Ingrate (Short), 1908 The 1916 Intolerance: Love's Struggle Throughout the Ages, 1915 Taming of the Shrew (Short), 1908 The Call of the Wild (Short), The Birth of a Nation, 1914 The Escape, 1914 Home, Sweet 1908 Romance of a Jewess (Short), 1908 The Planter's Wife Home, 1914 The Massacre (Short), 1913 The Mistake (Short), (Short), 1908 The Vaquero's Vow (Short), 1908 Ingomar, the and 1912 Grannie. -

British Film Journalism

Good of its kind? British film journalism HALL, Sheldon <http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0950-7310> Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/12366/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version HALL, Sheldon (2017). Good of its kind? British film journalism. In: HUNTER, Ian Q., PORTER, Laraine and SMITH, Justin, (eds.) The Routledge History of British Cinema. London, Routledge, 271-281. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk GOOD OF ITS KIND? BRITISH FILM JOURNALISM Sheldon Hall In his introduction to the 1986 collection All Our Yesterdays: 90 Years of British Cinema, Charles Barr noted that successive phases in the history of minority film culture in the UK have been signposted by the appearance of a series of small-circulation journals, each of which in turn represented “the ‘leading edge’ or growth point of film criticism in Britain” (5). These journals were, in order of their appearance: Close-Up, first published in 1927; Cinema Quarterly (1932) and its direct successors World Film News (1936) and Documentary News Letter (1940), all linked to the documentary movement; Sequence (1947); Sight and Sound (1949, the date when the longstanding BFI house journal’s editorship was assumed by Sequence alumnus Gavin Lambert); Movie (1962); and Screen (1971, again the date of a change in editorial direction rather than a first issue as such). -

Flávia Alessandra Final- (Alessandra Negrini) Com Os Fi- Personalidade Ficará Definida Mente Poderá Circular Lhos Na Escola, Juntos C Felizes, Para O Público

Catalogo de "Personalidades" da "Coleção Clipping da Editora Abril": Os Intelectuais. Volume I 10 FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS E LETRAS DE ASSIS CEDAP - CENTRO DE DOCUMENTAÇÃO E APOIO À PESQUISA Prof» Dr» Anna Maria Martínez Corrêa Reitor: Júlio Cezar Durigan Vice Reitor: Marilza Vieira Rudge Cunha Diretor: Ivan Esperança Rocha Vice Diretor: Ana Maria Rodrigues de Carvalhc Supervisora: Zélia Lopes da Silva Equipe: Tânia Regina de Luca (coordenação geral) Carolina Monteiro - historiógrafa e coordenadora técnica da equipe Bolsistas e voluntários: Aline de Jesus Nascimento Israel Alves Dias Neto João Lucas Poiani Trescentti Juliana Ubeda Busat Lucas Aparecido Mota Luciano Caetano Carneiro 2014 Sumário Apresentação: 17 Descrição da Coleção 23 Descrição do Tema 25 Gabriela Ri vero Abaroa 26 Senor Abravanel 28 Dener Pamplona de Abreu 30 Luciene Adami 32 KingSurmy Adé 34 Antônio Adolfo 36 João Albano 38 Herbert Alpert 40 Robert Burgess Aldrich 42 Flavia Alessandra 44 Dante Alighieri 46 Irwin Allen 48 WoodyAllen 50 Adriano Antônio de Almeida 52 Aracy Telles de Almeida 54 Carlos Alberto Vereza de Almeida 56 José Américo de Almeida 58 Manoel Carlos Gonçalves de Almeida 60 Maria de Medeiros 62 Paulo Sérgio de Almeida 64 12 Geraldo Alonso 66 Marco.Altberg 68 Louis Althusser 70 Robert Bernard Altman 72 José Alvarenga Júnior 74 Ataulfo Alves 76 Castro Alves 78 Francisco Alves 80 Jorge Amado 82 Andrei Amalrik 84 Suzana Amaral 86 José de Anchieta 88 Hans Christian Andersen 90 Lindsay Gordon Anderson 92 Michael Anderson 94 Roberta Joan Anderson 96 Carlos Drummond -

From Free Cinema to British New Wave: a Story of Angry Young Men

SUPLEMENTO Ideas, I, 1 (2020) 51 From Free Cinema to British New Wave: A Story of Angry Young Men Diego Brodersen* Introduction In February 1956, a group of young film-makers premiered a programme of three documentary films at the National Film Theatre (now the BFI Southbank). Lorenza Mazzetti, Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson thought at the time that “no film can be too personal”, and vehemently said so in their brief but potent manifesto about Free Cinema. Their documentaries were not only personal, but aimed to show the real working class people in Britain, blending the realistic with the poetic. Three of them would establish themselves as some of the most inventive and irreverent British filmmakers of the 60s, creating iconoclastic works –both in subject matter and in form– such as Saturday Day and Sunday Morning, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and If… Those were the first significant steps of a New British Cinema. They were the Big Screen’s angry young men. What is British cinema? In my opinion, it means many different things. National cinemas are much more than only one idea. I would like to begin this presentation with this question because there have been different genres and types of films in British cinema since the beginning. So, for example, there was a kind of cinema that was very successful, not only in Britain but also in America: the films of the British Empire, the films about the Empire abroad, set in faraway places like India or Egypt. Such films celebrated the glory of the British Empire when the British Empire was almost ending. -

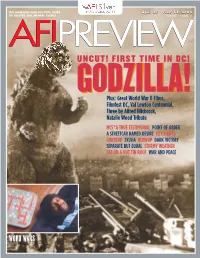

Uncut! First Time In

45833_AFI_AGS 3/30/04 11:38 AM Page 1 THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE GUIDE April 23 - June 13, 2004 ★ TO THEATRE AND MEMBER EVENTS VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 10 AFIPREVIEW UNCUT! FIRST TIME IN DC! GODZILLA!GODZILLA! Plus: Great World War II Films, Filmfest DC, Val Lewton Centennial, Three by Alfred Hitchcock, Natalie Wood Tribute MC5*A TRUE TESTIMONIAL POINT OF ORDER A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE CITY LIGHTS GODSEND SYLVIA BLOWUP DARK VICTORY SEPARATE BUT EQUAL STORMY WEATHER CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF WAR AND PEACE PHOTO NEEDED WORD WARS 45833_AFI_AGS 3/30/04 11:39 AM Page 2 Features 2, 3, 4, 7, 13 2 POINT OF ORDER MEMBERS ONLY SPECIAL EVENT! 3 MC5 *A TRUE TESTIMONIAL, GODZILLA GODSEND MEMBERS ONLY 4WORD WARS, CITY LIGHTS ●M ADVANCE SCREENING! 7 KIRIKOU AND THE SORCERESS Wednesday, April 28, 7:30 13 WAR AND PEACE, BLOWUP When an only child, Adam (Cameron Bright), is tragically killed 13 Two by Tennessee Williams—CAT ON A HOT on his eighth birthday, bereaved parents Rebecca Romijn-Stamos TIN ROOF and A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE and Greg Kinnear are befriended by Robert De Niro—one of Romijn-Stamos’s former teachers and a doctor on the forefront of Filmfest DC 4 genetic research. He offers a unique solution: reverse the laws of nature by cloning their son. The desperate couple agrees to the The Greatest Generation 6-7 experiment, and, for a while, all goes well under 6Featured Showcase—America Celebrates the the doctor’s watchful eye. Greatest Generation, including THE BRIDGE ON The “new” Adam grows THE RIVER KWAI, CASABLANCA, and SAVING into a healthy and happy PRIVATE RYAN young boy—until his Film Series 5, 11, 12, 14 eighth birthday, when things start to go horri- 5 Three by Alfred Hitchcock: NORTH BY bly wrong. -

Sport, Life, This Sporting Life, and the Hypertopia

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Sport, life, This Sporting Life, and the hypertopia AUTHORS Ewers, C JOURNAL Textual Practice DEPOSITED IN ORE 11 May 2021 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/125641 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Textual Practice ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rtpr20 Sport, life, This Sporting Life, and the hypertopia Chris Ewers To cite this article: Chris Ewers (2021): Sport, life, ThisSportingLife, and the hypertopia, Textual Practice, DOI: 10.1080/0950236X.2021.1900366 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/0950236X.2021.1900366 © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 16 Mar 2021. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 50 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rtpr20 TEXTUAL PRACTICE https://doi.org/10.1080/0950236X.2021.1900366 Sport, life, This Sporting Life, and the hypertopia Chris Ewers English Literature and Film, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK ABSTRACT Sport has classically been regarded as an ‘elsewhere’, a leisure activity set apart from the serious business of life. Sociological critiques of sport, however, emphasise its importance in transmitting ideology, and its responsiveness to historical change. The question, then, is how does this ‘elsewhere’ connect to the everyday? The article proposes that the spaces of sport generally function as a hypertopia, which involves a going beyond of the normative, rather than the Foucauldian idea of the heterotopia or utopia, which foreground difference. -

Lindsay Anderson: Sequence and the Rise of Auteurism in 1950S Britain Erik Hedling

Lindsay Anderson: Sequence and the rise of auteurism in 1950s Britain erik hedling T an upheaval in European film history. The financial losses of the Europeans, as compared to the Americans on the popular market, caused drastic changes within the European film industries, leading up to the continental government-subsidised film indus- tries of the present. Even if the historical reasons for the changes in Euro- pean film policies were mainly socio-economic, they were at the time mostly discussed and dealt with in aesthetic terms, and we saw eventually the emer- gence of the European art cinema, a new kind of film, specifically aimed at the literate and professional middle classes. One of the most important European contributions to the film history of the 1950s was, thus, undoubtedly the sudden rise of the auteur, the film director extraordinaire and the notion of the authored art film. Sweden had Ingmar Bergman, Italy had, for instance, Fellini, Rossellini, Visconti, and Antonioni, France had the Cahiers du Cinéma generation, towards the end of decade represented by the breakthrough of the nouvelle vague, with Truffaut, Godard, Rohmer and Chabrol. Traditionally, Britain has been said to have missed out on the development of auteurism and art cinema in the 1950s, instead clinging to its traditional industrial policies of trying to (albeit unsuccessfully) compete with the Americans on the popular market. (Peter Wollen’s essay on 1980s British films as ‘The Last New Wave’ is a good illustration of this attitude.)1 Even if this was true for the film industry, it is not entirely so for film culture as a whole, since Britain was at least intel- lectually at the very core of the foundation of the European art cinema in the 1950s, even if the art films as such – in the Bordwellian sense of personal vision, loose narrative structure, ambiguity and various levels of heightened realism – were not really to emerge until the 1960s (perhaps with the exception I was born in the mid-1950s and had my first overwhelming experience of the cinema watching Lindsay Anderson’s If … in 1969. -

PTFF 2006 Were Shot Digitally and Edited in a Living Room Somewhere

22 00 00 00 PP TT TT FF ~~ 22 00 00 66 22 00 00 11 22 00 00 66 PP oo r r t t TT oo ww nn ss ee nn dd FF i i l l mm FF ee ss t t i i vv aa l l - - SS ee pp t t ee mmbb ee r r 11 55 - - 11 77 , , 22 00 00 66 22 00 00 22 GGrreeeettiinnggss ffrroomm tthhee DDiirreeccttoorr 22 00 00 33 It is only human to want to improve, so each year the Port Townsend Film Festival continues to tweak its programming. In what 22 00 00 44 sometimes feels like a compulsive drive to create the perfect Festival, we add things one place, subtract in another, but mostly we 22 00 00 55 just add. Since our first year in 2000, we have added to our programming, in roughly chronological order: films of topical 22 00 00 66 interest, the extension of Taylor Street Outdoor Movies to Sunday 22 00 00 77 night, Almost Midnight movies, street musicians, Formative Films, the San Francisco-based National Public Radio program West Coast 22 00 00 88 Live!, the First Features sidebar, the continuous-run Drop-In Theatre, the Kids Film Camp, and A Moveable Fest, taking four Festival films 22 00 00 99 to the Historic Lynwood Theatre on Bainbridge Island. For 2006, we're adding two more innovations 22 00 11 00 advanced tickets sales, and 22 00 11 11 the Festival's own trailer. 22 00 11 22 The Festival has often been criticized for relying on passes and last minute "rush" tickets for box 22 00 11 33 office sales, so this year the Festival is selling a limited number of advance tickets for screenings at our largest venue, the Broughton Theatre at the high school. -

Madness in the Films of Karel Reisz, Lindsay Anderson, Sam Peckinpah and Nicolas Roeg

Journal of Alternative Perspectives in the Social Sciences (2020) Volume 10 No 4, 1413-1442 Images of Modernity: Madness in the Films of Karel Reisz, Lindsay Anderson, Sam Peckinpah and Nicolas Roeg Paul Cornelius—taught film studies and film and TV production at Mahidol University International College (Thailand), film studies and history at the University of Texas at Dallas, American studies at the University of Oldenburg (Germany), and communication arts at Southern Methodist University. Douglas Rhein—is Chair of the social science division at Mahidol University International College (Thailand), where he teaches classes in psychology and media. Abstract: This article will examine the work of four filmmakers-- Karel Reisz, Lindsay Anderson, Sam Peckinpah and Nicolas Roeg— whom have produced milestone works in the cinema that address one of the central concerns of modernity, the loss of individual identity and its replacement with a figurative disembodiment in an increasingly complex, technocratic, and specialized world. Preoccupation with the struggle for the soul and the resulting madness and the blurring and collapsing of boundaries, is what unites the four film makers. Three of the four--Reisz, Anderson and Roeg--originated in the British cinema, and thus automatically found themselves somewhat on the margins of the industry, yet the fourth, Peckinpah, is the sole American of the group. This article argues that his primary concerns in the cinema may place him more with his British counterparts than with other Hollywood filmmakers of the same era. The methodology chosen for this analysis firmly secures the films and their makers within their particular social and historical contexts. -

THE Permanent Crisis of FILM Criticism

mattias FILM THEORY FILM THEORY the PermaNENT Crisis of IN MEDIA HISTORY IN MEDIA HISTORY film CritiCism frey the ANXiety of AUthority mattias frey Film criticism is in crisis. Dwelling on the Kingdom, and the United States to dem the many film journalists made redundant at onstrate that film criticism has, since its P newspapers, magazines, and other “old origins, always found itself in crisis. The erma media” in past years, commentators need to assert critical authority and have voiced existential questions about anxieties over challenges to that author N E the purpose and worth of the profession ity are longstanding concerns; indeed, N T in the age of WordPress blogospheres these issues have animated and choreo C and proclaimed the “death of the critic.” graphed the trajectory of international risis Bemoaning the current anarchy of inter film criticism since its origins. net amateurs and the lack of authorita of tive critics, many journalists and acade Mattias Frey is Senior Lecturer in Film at film mics claim that in the digital age, cultural the University of Kent, author of Postwall commentary has become dumbed down German Cinema: History, Film History, C and fragmented into niche markets. and Cinephilia, coeditor of Cine-Ethics: riti Arguing against these claims, this book Ethical Dimensions of Film Theory, Prac- C examines the history of film critical dis tice, and Spectatorship, and editor of the ism course in France, Germany, the United journal Film Studies. AUP.nl 9789089647177 9789089648167 The Permanent Crisis of Film Criticism Film Theory in Media History explores the epistemological and theoretical founda- tions of the study of film through texts by classical authors as well as anthologies and monographs on key issues and developments in film theory. -

Tastes of Honey : the Making of Shelagh Delaney and a Cultural Revolution Pdf, Epub, Ebook

TASTES OF HONEY : THE MAKING OF SHELAGH DELANEY AND A CULTURAL REVOLUTION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Professor Selina Todd | 304 pages | 29 Aug 2019 | Vintage Publishing | 9781784740825 | English | London, United Kingdom Tastes of Honey : The Making of Shelagh Delaney and a Cultural Revolution PDF Book Jo becomes pregnant after a short-lived relationship with a black seafarer and during her pregnancy finds friendship and support from her gay friend Geoffrey. The downbeat tale of a young woman's pregnancy following a one-night stand with a black sailor, and her supportive relationship with a gay artist, verged on scandalous, but the play had successful runs in London and New York. View previous newsletters. That bombed; in contrast, her supporters advanced — above all, perhaps, when her disciple Tony Warren went on to create the Delaney-flavoured Coronation Street for Granada in even though she refused to write for the soap. Jocelyn Chatterton rated it it was amazing Jan 08, To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. Facebook Twitter Pinterest. Down in London, the advent of the Look Back in Anger generation John Osborne and Arnold Wesker above all signalled that outsiders might now barge through a few hallowed portals of drama. Paul rated it really liked it Dec 14, Jo also begins a relationship with her first love, a black sailor. Characteristics: pages, 16 unnumbered pages of plates : illustrations some color ; 23 cm. Jad Adams. Paul Robinson rated it it was amazing Mar 24, With its two generations of single mothers, its relaxed acceptance of black and gay characters, its frank and funny challenge to the prevailing taboos of race, class and sexuality, the play and its reception both marked a social upheaval, and played a major part in pushing it into fresh territory. -

Chicago Tribune

Chicago Tribune: ARTICLES ABOUT LILLIAN GISH Lillian Gish Relents, Enjoys Comedic Role May 15, 1986|By Peter B. Flint, New York Times News Service. NEW YORK — Lillian Gish`s fame is rooted in drama and tragedy, but, for her 104th film, the legendary actress has chosen a comedy. In ``Sweet Liberty,`` Alan Alda`s genial spoof of movie making, she portrays, all too briefly, the hero`s cantankerous but beguiling mother, who has slept in her living room for 11 years ``because the devil is in the bedroom.`` The hero (Alda), asked how long his mother has been crazy, replies, ``All my life.`` Gish said she was at first reluctant to portray such a quirky character but agreed to do so during a talk with Alda because he is such ``a beautiful, charming man.`` Your face, she said, mirrors your soul. ``Sweet Liberty,`` which Alda also wrote and directed, centers on a professor who is plunged into a summer of madness when a film company comes to his campus to make a movie of his book about the American Revolution. The comedy, co-starring Michelle Pfeiffer, Michael Caine and Lise Hilboldt, opens in Chicago Friday. Gish, who is 86, said her uneasiness over making a comedy faded quickly because of Alda`s ``thoughtful, gracious direction.`` ``My scenes were all amusing, and I had great fun playing the off-center woman,`` she remarked. ``The film was easier to make than most because it was shot in beautiful summer weather and nearby, around Sag Harbor, Long Island.`` ``Making the movie reminded me of D.W.