LOGOS: a Journal of Undergraduate Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christianese" and Golf! the Player Made a Tian Folks Could Learn Something from Critics Clamor for "Birdie," but Another Guy Hit an the Sports World

MAY 2016 NEWSLETTER Serving our King in 2016!! 6608 16th Street, Rio Linda, California 95673 Ph: (916) 991-5870 www.calvarybaptistchurchriolinda.org *****************************************S E R V I C ES************************************** SUNDAY:_______________________ ___ WEDNESDAY ____ __SATURDAY_ Sunday School—10:00 AM Morning Service—11:00 AM Prayer & Worship Men’s Prayer God’s Truth | Children | Missions Evening Service—6:00 PM AWANA—5:30 PM 7:00 PM 6:00 PM Pastor Robert Jupp presents: "Christianese" And golf! The player made a tian folks could learn something from Critics Clamor for "birdie," but another guy hit an the sports world. Change "eagle." He was "five under Do we have Christian terms that by Dr Shelton Smith par" (sorry he was feeling ill). Then the unsaved people don't under- somebody yelled "Fore!" What for? stand? Yes, we do! But hang on a minute. We've got Do we have a "Christianese" that PASTOR JUPP If you go to a major league baseball game, visitors in the stadium (arena) who we speak? Absolutely! you may find from twenty-five to fifty have never been here before. Do they Do we need to leave off our Chris- thousand people packed in the sta- understand all of this sports lingo? I tian verbiage in the presence of new- dium. Do you think everybody in at- assure you they do not. They don't comers? Absolutely not! tendance understands the language of know half of what we're talking about. We need to welcome them into our 'baseballese"? So does that stop the teams from "arena" (the church house) and then For example, the batter "flied out" playing the game exactly as they al- excitedly play our game. -

Design of Temperature and Humidity Control on Arabica Coffee Storage

International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) ISSN: 2278-3075, Volume-9 Issue-4, February 2020 Design of Temperature and Humidity Control on Arabica Coffee Storage Erna Kusuma Wati, Fitria Hidayanti, Aji Prasetya maintained. The DHT 11 sensor will measure temperature Abstract: Storage of coffee beans is essential to maintain the and humidity, and will be managed by Arduino-Uno so that quality of coffee in terms of water content and humidity. So we the coffee bean storage room will have a temperature and need a storage room with a stable temperature and humidity. In humidity following the expected set-points. this research, we will design a post-harvest coffee bean storage The storage room design is made of iron frame and system, by maintaining the condition of the room at a temperature of 19°-27°C with humidity of 60% -70%. The design uses block styrofoam walls and coated with plywood. Figure I (a) block diagrams and wiring diagrams, then makes a coffee bean storage diagram illustrates in general how the circuit works as a box by using a fan as an actuator, and a DHT 11 sensor to whole. measure the temperature and humidity of the room. The results of this study are the Arduino -Uno based Arabica coffee bean storage box takes 7 hours to get the expected set-point. the storage room has a temperature of 19°-27°C and humidity 60-70% Keywords : About four key words or phrases in alphabetical order, separated by commas. I. INTRODUCTION Storage of coffee beans is the next process to save the coffee from failure or loss of quality and wait for the following method. -

Religious Practices in the Workplace

Occasional Paper 3 Religious Practices in the Workplace BY SIMON WEBLEY Published by the Institute of Business Ethics 3 r e p a P l a n o i s a c c O Author Simon Webley is Research Director at the Institute of Business Ethics. He has published a number of studies on business ethics, the more recent being: Making Business Ethics Work (2006), Use of Codes of Ethics in Business (2008), and Employee Views of Ethics at Work: The 2008 National Survey (2009). Acknowledgements A number of people helped with this paper. Thank you to the research team at the Institute: Nicole Dando, Judith Irwin and Sabrina Basran. Katherine Bradshaw and Philippa Foster Back challenged my approach to the topic with constructive comments. Paul Woolley (Ethos), Denise Keating and Alan Beazley (Employers Forum on Belief) and Paul Hyman (Rolls Royce, UK) and Charles Giesting (Roll Royce, US) reviewed the penultimate draft providing suggestions all of which I think helped to root the paper in reality. Finally, I am grateful to the Tannenbaum Center for Interreligious Understanding in New York for permission to reproduce their Religious Diversity Checklist in an Appendix. Thank you to them all. All rights reserved. To reproduce or transmit this book in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, please obtain prior permission in writing from the publisher. Religious Practices in the Workplace Price £10 ISBN 978-0-9562183-5-3 © IBE www.ibe.org.uk First published March 2011 by the Institute of Business Ethics 24 Greencoat Place London SW1P 1BE The Institute’s website (www.ibe.org.uk) provides information on IBE publications, events and other aspects of its work. -

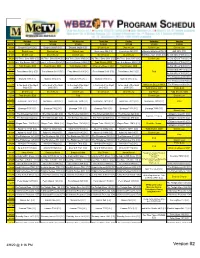

Me-TV Net Listings for 3-9-20

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday METV 3/9/20 3/10/20 3/11/20 3/12/20 3/13/20 3/14/20 3/15/20 06:00A Dragnet 30243 {CC} Dragnet 28205 {CC} Dragnet 28206 {CC} Dietrich Law Dietrich Law Dietrich Law Dietrich Law 06:30A Dietrich Law Dietrich Law Dietrich Law I Love Lucy 056 {CC} I Love Lucy 045 {CC} The Beverly Hillbillies 6705 {CC} ALF 4012 {CC} 07:00A Dietrich Law Dietrich Law Dietrich Law Dietrich Law Dietrich Law Bat Masterson 1055ASaved {CC} by the Bell (E/I) AFQ06 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 07:30A My Three Sons 0033 {CC} My Three Sons 0034 {CC} My Three Sons 0035 {CC} My Three Sons 0036 {CC} My Three Sons 0037 {CC} Dietrich LawSaved by the Bell (E/I) AFR10 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 08:00ALeave It to Beaver 0921A {CC}Leave It to Beaver 0923A {CC}Leave It to Beaver 0926A {CC} Todd Shatkin, DDS Leave It to Beaver 0929A {CC} Saved by the Bell (E/I) AFQ14 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 08:30A Todd Shatkin, DDS Todd Shatkin, DDS Todd Shatkin, DDS What's the Buzz in WNY Todd Shatkin, DDS Saved by the Bell (E/I) AFQ10 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 09:00A Saved by the Bell (E/I) AFP13 {CC} <E/I-13-16> Perry Mason 6412 {CC} Perry Mason 6413 {CC} Perry Mason 6414 {CC} Perry Mason 6415 {CC} Perry Mason 6417 {CC} Paid 09:30A Saved by the Bell (E/I) AFQ17 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 10:00A The Flintstones 006 {CC} Matlock 8801 {CC} Matlock 8804 {CC} Matlock 8805 {CC} Matlock 8806 {CC} Matlock 8807 {CC} 10:30A The Flintstones 007 {CC} 11:00A In the Heat of the Night In the Heat of the Night In the Heat of the Night In the Heat of the Night In the Heat of the Night What's the Buzz -

The Disability Drive by Anna Mollow a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree of Docto

The Disability Drive by Anna Mollow A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kent Puckett, Chair Professor Celeste G. Langan Professor Melinda Y. Chen Spring 2015 The Disability Drive © Anna Mollow, 2015. 1 Abstract The Disability Drive by Anna Mollow Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California Berkeley Professor Kent Puckett, Chair This dissertation argues that the psychic force that Freud named “the death drive” would more precisely be termed “the disability drive.” Freud‟s concept of the death drive emerged from his efforts to account for feelings, desires, and actions that seemed not to accord with rational self- interest or the desire for pleasure. Positing that human subjectivity was intrinsically divided against itself, Freud suggested that the ego‟s instincts for pleasure and survival were undermined by a competing component of mental life, which he called the death drive. But the death drive does not primarily refer to biological death, and the term has consequently provoked confusion. By distancing Freud‟s theory from physical death and highlighting its imbrication with disability, I revise this important psychoanalytic concept and reveal its utility to disability studies. While Freud envisaged a human subject that is drawn, despite itself, toward something like death, I propose that this “something” can productively be understood as disability. In addition, I contend that our culture‟s repression of the disability drive, and its resultant projection of the drive onto stigmatized minorities, is a root cause of multiple forms of oppression. -

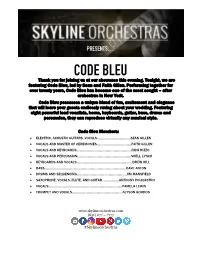

CODE BLEU Thank You for Joining Us at Our Showcase This Evening

PRESENTS… CODE BLEU Thank you for joining us at our showcase this evening. Tonight, we are featuring Code Bleu, led by Sean and Faith Gillen. Performing together for over twenty years, Code Bleu has become one of the most sought – after orchestras in New York. Code Bleu possesses a unique blend of fun, excitement and elegance that will leave your guests endlessly raving about your wedding. Featuring eight powerful lead vocalists, horns, keyboards, guitar, bass, drums and percussion, they can reproduce virtually any musical style. Code Bleu Members: • ELECTRIC, ACOUSTIC GUITARS, VOCALS………………………..………SEAN GILLEN • VOCALS AND MASTER OF CEREMONIES……..………………………….FAITH GILLEN • VOCALS AND KEYBOARDS..…………………………….……………………..RICH RIZZO • VOCALS AND PERCUSSION…………………………………......................SHELL LYNCH • KEYBOARDS AND VOCALS………………………………………..………….…DREW HILL • BASS……………………………………………………………………….….......DAVE ANTON • DRUMS AND SEQUENCING………………………………………………..JIM MANSFIELD • SAXOPHONE, VOCALS, FLUTE, AND GUITAR….……………ANTHONY POLICASTRO • VOCALS………………………………………………………………….…….PAMELA LEWIS • TRUMPET AND VOCALS……………….…………….………………….ALYSON GORDON www.skylineorchestras.com (631) 277 – 7777 #Skylineorchestras DANCE : BURNING DOWN THE HOUSE – Talking Heads BUST A MOVE – Young MC A GOOD NIGHT – John Legend CAKE BY THE OCEAN – DNCE A LITTLE LESS CONVERSATION – Elvis CALL ME MAYBE – Carly Rae Jepsen A LITTLE PARTY NEVER KILLED NOBODY – Fergie CAN’T FEEL MY FACE – The Weekend A LITTLE RESPECT – Erasure CAN’T GET ENOUGH OF YOUR LOVE – Barry White A PIRATE LOOKS AT 40 – Jimmy Buffet CAN’T GET YOU OUT OF MY HEAD – Kylie Minogue ABC – Jackson Five CAN’T HOLD US – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis ACCIDENTALLY IN LOVE – Counting Crows CAN’T HURRY LOVE – Supremes ACHY BREAKY HEART – Billy Ray Cyrus CAN’T STOP THE FEELING – Justin Timberlake ADDICTED TO YOU – Avicii CAR WASH – Rose Royce AEROPLANE – Red Hot Chili Peppers CASTLES IN THE SKY – Ian Van Dahl AIN’T IT FUN – Paramore CHEAP THRILLS – Sia feat. -

GENRE STUDIES in MASS MEDIA Art Silverblatt Is Professor of Communications and Journalism at Webster Univer- Sity, St

GENRE STUDIES IN MASS MEDIA Art Silverblatt is Professor of Communications and Journalism at Webster Univer- sity, St. Louis, Missouri. He earned his Ph.D. in 1980 from Michigan State University. He is the author of numerous books and articles, including Media Literacy: Keys to Interpreting Media Messages (1995, 2001), The Dictionary of Media Literacy (1997), Approaches to the Study of Media Literacy (M.E. Sharpe, 1999), and International Communications: A Media Literacy Approach (M.E. Sharpe, 2004). Silverblatt’s work has been translated into Japanese, Korean, Chinese, and German. GENRE STUDIES IN MASS MEDIA A HANDBOOK ART SILVERBLATT M.E.Sharpe Armonk, New York London, England Copyright © 2007 by M.E. Sharpe, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher, M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 80 Business Park Drive, Armonk, New York 10504. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Silverblatt, Art. Genre studies in mass media : a handbook / Art Silverblatt. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN: 978-0-7656-1669-2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Mass media genres. I. Title. P96.G455S57 2007 302.23—dc22 2006022316 Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z 39.48-1984. ~ BM (c) 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my “first generation” of friends, who have been supportive for so long: Rick Rosenfeld, Linda Holtzman, Karen Techner, John Goldstein, Alan Osherow, and Gary Tobin. -

1 Revelation: Unveiling Reality “Sex, Money and Jezebel” Revelation 2:18-29 Kevin Haah April 17, 2016

Revelation: Unveiling Reality “Sex, Money and Jezebel” Revelation 2:18-29 Kevin Haah April 17, 2016 Turn on Timer! [Slide 1] We are in a middle of a series entitled, “Revelation: Unveiling Reality.” Revelation was written to show us that reality is more than what we see with our eyes. That’s the thesis of the book: things are not as they seem. This book unveils reality not just of the future, but also of the present. There is more to this present moment then we can know with our unaided senses. The more we see this, the more our perspective toward life changes. We see the world differently. We see the pressures and stresses of our lives differently. So, this is a practical book. It helps us be faithful even during hardships! Today, we are going to look at one of the letters to the seven churches, the letter to the church in Thyatira. [Slide 2] Today’s sermon is entitled, “Sex, Money and Jezebel.” [Slide 3] Let’s go to Revelation 2:18-29: 18 “To the angel of the church in Thyatira write: These are the words of the Son of God, whose eyes are like blazing fire and whose feet are like burnished bronze. 19 I know your deeds, your love and faith, your service and perseverance, and that you are now doing more than you did at first. [Slide 4] 20 Nevertheless, I have this against you: You tolerate that woman Jezebel, who calls herself a prophet. By her teaching she misleads my servants into sexual immorality and the eating of food sacrificed to idols. -

Of Mainstream Religion in Australia

Is 'green' religion the solution to the ecological crisis? A case study of mainstream religion in Australia by Steven Murray Douglas Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University March 2008 ii Candidate's Declaration This thesis contains no material that has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. To the best of the author’s knowledge, it contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text. Steven Murray Douglas Date: iii Acknowledgements “All actions take place in time by the interweaving of the forces of nature; but the man lost in selfish delusion thinks he himself is the actor.” (Bhagavad Gita 3:27). ‘Religion’ remains a somewhat taboo subject in Australia. When combined with environmentalism, notions of spirituality, the practice of criticality, and the concept of self- actualisation, it becomes even harder to ‘pigeonhole’ as a topic, and does not fit comfortably into the realms of academia. In addition to the numerous personal challenges faced during the preparation of this thesis, its very nature challenged the academic environment in which it took place. I consider that I was fortunate to be able to undertake this research with the aid of a scholarship provided by the Fenner School of Environment & Society and the College of Science. I acknowledge David Dumaresq for supporting my scholarship application and candidature, and for being my supervisor for my first year at ANU. Emeritus Professor Valerie Brown took on the role of my supervisor in David’s absence during my second year. -

Religion and Attitudes to Corporate Social Responsibility in a Large Cross-Country Sample Author(S): S

Religion and Attitudes to Corporate Social Responsibility in a Large Cross-Country Sample Author(s): S. Brammer, Geoffrey Williams and John Zinkin Source: Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 71, No. 3 (Mar., 2007), pp. 229-243 Published by: Springer Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25075330 . Accessed: 11/04/2013 16:12 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Springer is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Business Ethics. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 141.161.133.194 on Thu, 11 Apr 2013 16:12:39 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Journal of Business Ethics (2007) 71:229-243 ? Springer 2006 DOI 10.1007/sl0551-006-9136-z and Attitudes to Corporate Religion S. Brammer Social in a Responsibility Large GeoffreyWilliams Cross-Country Sample John Zinkin ABSTRACT. This paper explores the relationship of the firm and that which is required by law" between denomination and individual attitudes religious (McWilliams and Siegel (2001) has become a more to Social within the Corporate Responsibility (CSR) salient aspect of corporate competitive contexts. context of a large sample of over 17,000 individuals In this climate, organised religion has sought to two drawn from 20 countries. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Disability Drive Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0bb4c3bv Author Mollow, Anna Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Disability Drive by Anna Mollow A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kent Puckett, Chair Professor Celeste G. Langan Professor Melinda Y. Chen Spring 2015 The Disability Drive © Anna Mollow, 2015. 1 Abstract The Disability Drive by Anna Mollow Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California Berkeley Professor Kent Puckett, Chair This dissertation argues that the psychic force that Freud named “the death drive” would more precisely be termed “the disability drive.” Freud‟s concept of the death drive emerged from his efforts to account for feelings, desires, and actions that seemed not to accord with rational self- interest or the desire for pleasure. Positing that human subjectivity was intrinsically divided against itself, Freud suggested that the ego‟s instincts for pleasure and survival were undermined by a competing component of mental life, which he called the death drive. But the death drive does not primarily refer to biological death, and the term has consequently provoked confusion. By distancing Freud‟s theory from physical death and highlighting its imbrication with disability, I revise this important psychoanalytic concept and reveal its utility to disability studies. While Freud envisaged a human subject that is drawn, despite itself, toward something like death, I propose that this “something” can productively be understood as disability. -

The BG News October 8, 1993

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 10-8-1993 The BG News October 8, 1993 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News October 8, 1993" (1993). BG News (Student Newspaper). 5585. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/5585 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ^ The BG News Friday, October 8, 1993 Bowling Green, Ohio Volume 76, Issue 32 Briefs Somalia gets more U.S. backup by Terence Hunt months" to complete the mission ness and chaos. He noted Clin- Weather The Associated Press but he hoped to wrap it up before ton's statement that there la no then. guarantee Somalia will rid itself Aspin said he hoped Clinton's of violence or suffering "but at Friday: Mostly sunny. WASHINGTON - President "We started this mission for the High 75 to 80. Winds south 5 decision would lead other nations least we will have given Somalia Clinton told the American people right reasons and we are going to to beef up their forces in Soma- a reasonable chance." to IS mph. Thursday he was sending 1,700 Friday night: Partly lia. "We believe the allies will Aspin defended himself more troops, heavy armor and finish it in the right way.