Oocyte Production, Fecundity, and Size at the Onset of Reproduction Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARINE FAUNA and FLORA of BERMUDA a Systematic Guide to the Identification of Marine Organisms

MARINE FAUNA AND FLORA OF BERMUDA A Systematic Guide to the Identification of Marine Organisms Edited by WOLFGANG STERRER Bermuda Biological Station St. George's, Bermuda in cooperation with Christiane Schoepfer-Sterrer and 63 text contributors A Wiley-Interscience Publication JOHN WILEY & SONS New York Chichester Brisbane Toronto Singapore ANTHOZOA 159 sucker) on the exumbrella. Color vari many Actiniaria and Ceriantharia can able, mostly greenish gray-blue, the move if exposed to unfavorable condi greenish color due to zooxanthellae tions. Actiniaria can creep along on their embedded in the mesoglea. Polyp pedal discs at 8-10 cm/hr, pull themselves slender; strobilation of the monodisc by their tentacles, move by peristalsis type. Medusae are found, upside through loose sediment, float in currents, down and usually in large congrega and even swim by coordinated tentacular tions, on the muddy bottoms of in motion. shore bays and ponds. Both subclasses are represented in Ber W. STERRER muda. Because the orders are so diverse morphologically, they are often discussed separately. In some classifications the an Class Anthozoa (Corals, anemones) thozoan orders are grouped into 3 (not the 2 considered here) subclasses, splitting off CHARACTERISTICS: Exclusively polypoid, sol the Ceriantharia and Antipatharia into a itary or colonial eNIDARIA. Oral end ex separate subclass, the Ceriantipatharia. panded into oral disc which bears the mouth and Corallimorpharia are sometimes consid one or more rings of hollow tentacles. ered a suborder of Scleractinia. Approxi Stomodeum well developed, often with 1 or 2 mately 6,500 species of Anthozoa are siphonoglyphs. Gastrovascular cavity compart known. Of 93 species reported from Ber mentalized by radially arranged mesenteries. -

Coelenterata: Anthozoa), with Diagnoses of New Taxa

PROC. BIOL. SOC. WASH. 94(3), 1981, pp. 902-947 KEY TO THE GENERA OF OCTOCORALLIA EXCLUSIVE OF PENNATULACEA (COELENTERATA: ANTHOZOA), WITH DIAGNOSES OF NEW TAXA Frederick M. Bayer Abstract.—A serial key to the genera of Octocorallia exclusive of the Pennatulacea is presented. New taxa introduced are Olindagorgia, new genus for Pseudopterogorgia marcgravii Bayer; Nicaule, new genus for N. crucifera, new species; and Lytreia, new genus for Thesea plana Deich- mann. Ideogorgia is proposed as a replacement ñame for Dendrogorgia Simpson, 1910, not Duchassaing, 1870, and Helicogorgia for Hicksonella Simpson, December 1910, not Nutting, May 1910. A revised classification is provided. Introduction The key presented here was an essential outgrowth of work on a general revisión of the octocoral fauna of the western part of the Atlantic Ocean. The far-reaching zoogeographical affinities of this fauna made it impossible in the course of this study to ignore genera from any part of the world, and it soon became clear that many of them require redefinition according to modern taxonomic standards. Therefore, the type-species of as many genera as possible have been examined, often on the basis of original type material, and a fully illustrated generic revisión is in course of preparation as an essential first stage in the redescription of western Atlantic species. The key prepared to accompany this generic review has now reached a stage that would benefit from a broader and more objective testing under practical conditions than is possible in one laboratory. For this reason, and in order to make the results of this long-term study available, even in provisional form, not only to specialists but also to the growing number of ecologists, biochemists, and physiologists interested in octocorals, the key is now pre- sented in condensed form with minimal illustration. -

Octocoral Physiology: Calcium Carbonate Composition and the Effect of Thermal Stress on Enzyme Activity

OCTOCORAL PHYSIOLOGY: CALCIUM CARBONATE COMPOSITION AND THE EFFECT OF THERMAL STRESS ON ENZYME ACTIVITY by Hadley Jo Pearson A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2014 Approved by Advisor: Dr. Tamar Goulet Reader: Dr. Gary Gaston Reader: Dr. Marc Slattery © 2014 Hadley Jo Pearson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank everyone who has helped me to make this thesis a reality. First, I would like to thank Dr. Tamar L. Goulet for her direction in helping me both to choose my topics of study, and to find the finances needed for me to participate in field research in Mexico. Her help in cleaning up my writing was greatly needed and appreciated. I would also like to thank Kartick Shirur. This project would have been completely impossible without his gracious, continuous help over the past three years. Our many late nights in the lab would have been unbearable without his patience, humor, and impeccable taste in music. Thank you for teaching me so much, while keeping my spirits high. Your contributions are invaluable. I would be remiss in not also thanking my other travel companions from my two summers in Mexico: Dr. Denis Goulet, Blake Ramsby, Mark McCauley, and Lauren Camp. Thank you for teaching and helping me along this very, very long journey. I thank my other thesis readers for their time and effort: Dr. Gary Gaston and Dr. Marc Slattery. Also, thank you to Dr. Colin Jackson for the use of his laboratory equipment. -

Observations on the Size, Predators and Tumor-Like Outgrowths of Gorgonian Octocoral Colonies in the Area of Santa Marta, Caribbean Coast of Colombia

Northeast Gulf Science Volume 11 Article 1 Number 1 Number 1 7-1990 Observations on the Size, Predators and Tumor- Like Outgrowths of Gorgonian Octocoral Colonies in the Area of Santa Marta, Caribbean Coast of Colombia Leonor Botero Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas de Punta de Betin INVEMAR DOI: 10.18785/negs.1101.01 Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/goms Recommended Citation Botero, L. 1990. Observations on the Size, Predators and Tumor-Like Outgrowths of Gorgonian Octocoral Colonies in the Area of Santa Marta, Caribbean Coast of Colombia. Northeast Gulf Science 11 (1). Retrieved from https://aquila.usm.edu/goms/vol11/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gulf of Mexico Science by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Botero: Observations on the Size, Predators and Tumor-Like Outgrowths of Northeast Gulf Science Vol. 11, No. 1 July 1990 p. 1-10 OBSERVATIONS ON THE SIZE, PREDATORS AND TUMOR-LIKE OUTGROWTHS OF GORGONIAN OCTOCORAL COLONIES IN THE AREA OF SANTA MARTA, CARIBBEAN COAST OF COLOMBIA Leonor Botero Institute de Investigaciones Marinas de Punta de Betin INVEMAR Apartado Aereo 1016 Santa Marta, Colombia South America ABSTRACT: Gorgon ian communities of the Santa Marta area are dominated by species with large numbers of large colonies (height ;;.40 em) in contrast to that reported for other Caribbean sites where species with large numbers of small (<10 em in height) colonies are predominant. -

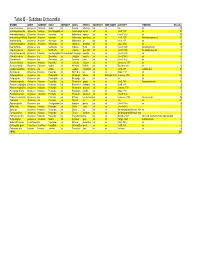

Table B – Subclass Octocorallia

Table B – Subclass Octocorallia BINOMEN ORDER SUBORDER FAMILY SUBFAMILY GENUS SPECIES SUBSPECIES COMN_NAMES AUTHORITY SYNONYMS #Records Acanella arbuscula Alcyonacea Calcaxonia Isididae n/a Acanella arbuscula n/a n/a n/a n/a 59 Acanthogorgia armata Alcyonacea Holaxonia Acanthogorgiidae n/a Acanthogorgia armata n/a n/a Verrill, 1878 n/a 95 Anthomastus agassizii Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Anthomastus agassizii n/a n/a (Verrill, 1922) n/a 35 Anthomastus grandiflorus Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Anthomastus grandiflorus n/a n/a Verrill, 1878 Anthomastus purpureus 37 Anthomastus sp. Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Anthomastus sp. n/a n/a Verrill, 1878 n/a 1 Anthothela grandiflora Alcyonacea Scleraxonia Anthothelidae n/a Anthothela grandiflora n/a n/a (Sars, 1856) n/a 24 Capnella florida Alcyonacea n/a Nephtheidae n/a Capnella florida n/a n/a (Verrill, 1869) Eunephthya florida 44 Capnella glomerata Alcyonacea n/a Nephtheidae n/a Capnella glomerata n/a n/a (Verrill, 1869) Eunephthya glomerata 4 Chrysogorgia agassizii Alcyonacea Holaxonia Acanthogorgiidae Chrysogorgiidae Chrysogorgia agassizii n/a n/a (Verrill, 1883) n/a 2 Clavularia modesta Alcyonacea n/a Clavulariidae n/a Clavularia modesta n/a n/a (Verrill, 1987) n/a 6 Clavularia rudis Alcyonacea n/a Clavulariidae n/a Clavularia rudis n/a n/a (Verrill, 1922) n/a 1 Gersemia fruticosa Alcyonacea Alcyoniina Alcyoniidae n/a Gersemia fruticosa n/a n/a Marenzeller, 1877 n/a 3 Keratoisis flexibilis Alcyonacea Calcaxonia Isididae n/a Keratoisis flexibilis n/a n/a Pourtales, 1868 n/a 1 Lepidisis caryophyllia Alcyonacea n/a Isididae n/a Lepidisis caryophyllia n/a n/a Verrill, 1883 Lepidisis vitrea 13 Muriceides sp. -

The Genetic Identity of Dinoflagellate Symbionts in Caribbean Octocorals

Coral Reefs (2004) 23: 465-472 DOI 10.1007/S00338-004-0408-8 REPORT Tamar L. Goulet • Mary Alice CofFroth The genetic identity of dinoflagellate symbionts in Caribbean octocorals Received: 2 September 2002 / Accepted: 20 December 2003 / Published online: 29 July 2004 © Springer-Verlag 2004 Abstract Many cnidarians (e.g., corals, octocorals, sea Introduction anemones) maintain a symbiosis with dinoflagellates (zooxanthellae). Zooxanthellae are grouped into The cornerstone of the coral reef ecosystem is the sym- clades, with studies focusing on scleractinian corals. biosis between cnidarians (e.g., corals, octocorals, sea We characterized zooxanthellae in 35 species of Caribbean octocorals. Most Caribbean octocoral spe- anemones) and unicellular dinoñagellates commonly called zooxanthellae. Studies of zooxanthella symbioses cies (88.6%) hosted clade B zooxanthellae, 8.6% have previously been hampered by the difficulty of hosted clade C, and one species (2.9%) hosted clades B and C. Erythropodium caribaeorum harbored clade identifying the algae. Past techniques relied on culturing and/or identifying zooxanthellae based on their free- C and a unique RFLP pattern, which, when se- swimming form (Trench 1997), antigenic features quenced, fell within clade C. Five octocoral species (Kinzie and Chee 1982), and cell architecture (Blank displayed no zooxanthella cladal variation with depth. 1987), among others. These techniques were time-con- Nine of the ten octocoral species sampled throughout suming, required a great deal of expertise, and resulted the Caribbean exhibited no regional zooxanthella cla- in the differentiation of only a small number of zoo- dal differences. The exception, Briareum asbestinum, xanthella species. Molecular techniques amplifying had some colonies from the Dry Tortugas exhibiting zooxanthella DNA encoding for the small and large the E. -

Heterotrophic Feeding by Gorgonian Corals with Symbiotic Zooxanthella

Heterotrophic feeding by gorgonian corals with symbiotic zooxanthella Marta Ribes, Rafel Coma, and Josep-Maria Gili Institut de Ciències del Mar, Passeig Joan de Borbó s/n, 08039 Barcelona, Spain Abstract Gorgonians are one of the most characteristic groups in Caribbean coral reef communities. In this study, we measured in situ rates of grazing on pico-, nano-, and microplankton, zooxanthellae release, and respiration for the ubiquitous symbiotic gorgonian coral Plexaura flexuosa. Zooplankton capture by P. flexuosa and Pseudoplexaura porosa was quantified by examination of stomach contents. In nature, both species captured zooplankton prey ranging from 100 to 700 µm, at a grazing rate of 0.09 and 0.23 prey polyp-1 d-l, respectively. Because of the greater mean size of the prey and the higher mean prey capture per polyp, P. porosa obtained 3.4 × l0-s mg C polyp-1 d-l from zooplankton, about four times the grazing rate of P. flexuosa. On average, P. flexuosa captured 7.2 ± 1.9 microorganisms polyp-1 d-l including ciliates, dinoflagellates, and diatoms, but they did not appear to graze significantly on organisms <5 µm (heterotrophic bacteria, Prochlorococcus sp., Synechococcus sp., or pi- coeukaryotes). Zooplankton and microbial prey accounted for only 0.4% of respiratory requirements in P. flexuosa, but they contributed 17% of nitrogen required annually for new production (growth and reproduction). Although the contribution of microbial prey to gorgonian energetics was low, dense gorgonian populations found on many Caribbean reefs may be important grazers of plankton communities. The role of food as a constraining factor in population and photosynthetic products are deficient in nutrients such. -

In Situ Rates of Fertilization Among Broadcast Spawning Gorgonian Corals

Reference: Biol. Bull. 190: 45-55. (February, 1996) In situ Rates of Fertilization Among Broadcast Spawning Gorgonian Corals HOWARD R. LASKER, DANIEL A. BRAZEAU1, JULIO CALDERON2, MARY ALICE COFFROTH, RAFEL COMA, AND KIHO KIM Department of Biological Sciences, State University of New York at Buffalo, g#z/o,#ew Fort 74260 Abstract. Fertilization rates among marine benthic column as gametes are diluted, spawning behavior of taxa have implicitly been assumed to be uniformly high the gorgonians, and the current regime. Fertilization in most analyses of life history evolution, but in situ rates are often low and may represent a limiting step fertilization rates during natural spawning events are in recruitment during some years. Low fertilization rates rarely measured. Fertilization rates of the Caribbean may also be an important component of the life history gorgonians Plexaura kuna and Pseudoplexaura porosa evolution of these species. were measured at a site in the San Bias Islands, Panama, by collecting eggs downstream of colonies during syn- Introduction chronous spawning events during the summer months in the years 1988-1994. Eggs collected by divers were One of the primary goals of benthic ecology has been incubated, and the proportion of eggs that developed the determination of the factors limiting populations. For was determined. Proportions of eggs developing suggest most of this century, such efforts have been concentrated fertilization rates that vary from 0% to 100%. Monthly on post-recruitment events in the life history of the or- means ranged from 0% to 60.4%. Failure of gametes to ganism (i.e., Connell, 1961, and hundreds of subsequent develop can be attributed to sperm limitation, as eggs studies). -

Deep-Sea Coral Taxa in the U. S. Caribbean Region: Depth And

Deep‐Sea Coral Taxa in the U. S. Caribbean Region: Depth and Geographical Distribution By Stephen D. Cairns1 1. National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC An update of the status of the azooxanthellate, heterotrophic coral species that occur predominantly deeper than 50 m in the U.S. Caribbean territories is not given in this volume because of lack of significant additional data. However, an updated list of deep‐sea coral species in Phylum Cnidaria, Classes Anthozoa and Hydrozoa, from the Caribbean region (Figure 1) is presented below. Details are provided on depth ranges and known geographic distributions within the region (Table 1). This list is adapted from Lutz & Ginsburg (2007, Appendix 8.1) in that it is restricted to the U. S. territories in the Caribbean, i.e., Puerto Rico, U. S. Virgin Islands, and Navassa Island, not the entire Caribbean and Bahamian region. Thus, this list is significantly shorter. The list has also been reordered alphabetically by family, rather than species, to be consistent with other regional lists in this volume, and authorship and publication dates have been added. Also, Antipathes americana is now properly assigned to the genus Stylopathes, and Stylaster profundus to the genus Stenohelia. Furthermore, many of the geographic ranges have been clarified and validated. Since 2007 there have been 20 species additions to the U.S. territories list (indicated with blue shading in the list), mostly due to unpublished specimens from NMNH collections. As a result of this update, there are now known to be: 12 species of Antipatharia, 45 species of Scleractinia, 47 species of Octocorallia (three with incomplete taxonomy), and 14 species of Stylasteridae, for a total of 118 species found in the relatively small geographic region of U. -

Tortugas Ecological Reserve

Strategy for Stewardship Tortugas Ecological Reserve U.S. Department of Commerce DraftSupplemental National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Environmental National Ocean Service ImpactStatement/ Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management DraftSupplemental Marine Sanctuaries Division ManagementPlan EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS), working in cooperation with the State of Florida, the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council, and the National Marine Fisheries Service, proposes to establish a 151 square nautical mile “no- take” ecological reserve to protect the critical coral reef ecosystem of the Tortugas, a remote area in the western part of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. The reserve would consist of two sections, Tortugas North and Tortugas South, and would require an expansion of Sanctuary boundaries to protect important coral reef resources in the areas of Sherwood Forest and Riley’s Hump. An ecological reserve in the Tortugas will preserve the richness of species and health of fish stocks in the Tortugas and throughout the Florida Keys, helping to ensure the stability of commercial and recreational fisheries. The reserve will protect important spawning areas for snapper and grouper, as well as valuable deepwater habitat for other commercial species. Restrictions on vessel discharge and anchoring will protect water quality and habitat complexity. The proposed reserve’s geographical isolation will help scientists distinguish between natural and human-caused changes to the coral reef environment. Protecting Ocean Wilderness Creating an ecological reserve in the Tortugas will protect some of the most productive and unique marine resources of the Sanctuary. Because of its remote location 70 miles west of Key West and more than 140 miles from mainland Florida, the Tortugas region has the best water quality in the Sanctuary. -

CNIDARIA Corals, Medusae, Hydroids, Myxozoans

FOUR Phylum CNIDARIA corals, medusae, hydroids, myxozoans STEPHEN D. CAIRNS, LISA-ANN GERSHWIN, FRED J. BROOK, PHILIP PUGH, ELLIOT W. Dawson, OscaR OcaÑA V., WILLEM VERvooRT, GARY WILLIAMS, JEANETTE E. Watson, DENNIS M. OPREsko, PETER SCHUCHERT, P. MICHAEL HINE, DENNIS P. GORDON, HAMISH J. CAMPBELL, ANTHONY J. WRIGHT, JUAN A. SÁNCHEZ, DAPHNE G. FAUTIN his ancient phylum of mostly marine organisms is best known for its contribution to geomorphological features, forming thousands of square Tkilometres of coral reefs in warm tropical waters. Their fossil remains contribute to some limestones. Cnidarians are also significant components of the plankton, where large medusae – popularly called jellyfish – and colonial forms like Portuguese man-of-war and stringy siphonophores prey on other organisms including small fish. Some of these species are justly feared by humans for their stings, which in some cases can be fatal. Certainly, most New Zealanders will have encountered cnidarians when rambling along beaches and fossicking in rock pools where sea anemones and diminutive bushy hydroids abound. In New Zealand’s fiords and in deeper water on seamounts, black corals and branching gorgonians can form veritable trees five metres high or more. In contrast, inland inhabitants of continental landmasses who have never, or rarely, seen an ocean or visited a seashore can hardly be impressed with the Cnidaria as a phylum – freshwater cnidarians are relatively few, restricted to tiny hydras, the branching hydroid Cordylophora, and rare medusae. Worldwide, there are about 10,000 described species, with perhaps half as many again undescribed. All cnidarians have nettle cells known as nematocysts (or cnidae – from the Greek, knide, a nettle), extraordinarily complex structures that are effectively invaginated coiled tubes within a cell. -

Reference DNA Barcodes and Other Mitochondrial Markers for Identifying Caribbean Octocorals

Biodiversity Data Journal 7: e30970 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.7.e30970 Research Article Reference DNA barcodes and other mitochondrial markers for identifying Caribbean Octocorals Jaime G. Morín‡, Dagoberto E. Venera-Pontón§, Amy C. Driskell|, Juan A. Sánchez¶, Howard R. Lasker#, Rachel Collin ¤ ‡ Laboratorio de Sistemática Molecular y Filogeografía, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Peru § Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Panama City, Panama | Laboratories of Analytical Biology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., United States of America ¶ Laboratorio de Biología Molecular Marina – BIOMMAR, Bogotá, Colombia # Department of Geology, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, United States of America ¤ Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Balboa, Panama Corresponding author: Rachel Collin ([email protected]) Academic editor: Danwei Huang Received: 31 Oct 2018 | Accepted: 04 Feb 2019 | Published: 20 Feb 2019 Citation: Morín J, Venera-Pontón D, Driskell A, Sánchez J, Lasker H, Collin R (2019) Reference DNA barcodes and other mitochondrial markers for identifying Caribbean Octocorals. Biodiversity Data Journal 7: e30970. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.7.e30970 Abstract DNA barcoding is a useful tool for documenting the diversity of metazoans. The most commonly used barcode markers, 16S and COI, are not considered suitable for species identification within some "basal" phyla of metazoans. Nevertheless metabarcoding studies of bulk mixed samples commonly use these markers and may obtain sequences for "basal" phyla. We sequenced mitochondrial DNA fragments of cytochrome oxidase c subunit I (COI), 16S ribosomal RNA (16S), NADH dehydrogenase subunits 2 (16S-ND2), 6 (ND6- ND3) and 4L (ND4L-MSH) for 27 species of Caribbean octocorals to create a reference barcode dataset and to compare the utility of COI and 16S to other markers more typically used for octocorals.