Design Lansing LANSING 2012 Comprehensive Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Primary Election Preview Free

PRIMARY ELECTION PREVIEW FREE a newspaper for the rest of us www.lansingcitypulse.com June 28 - July 4, 2017 CityPulse’s Summer of Art: "Couple at Lansing 4th of July Parade," by Carolyn Texera. See page 20 for story. Need a checking account? Need a car loan? Need a credit card? We got you. 1901 E Michigan Ave • Lansing’s Eastside • 517.484.0601 • gabrielscu.com 2 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • June 28, 2017 City Pulse • June 28, 2017 www.lansingcitypulse.com 3 4 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • June 28, 2017 VOL. 16 ISSUE 46 (517) 371-5600 • Fax: (517) 999-6061 • 1905 E. Michigan Ave. • Lansing, MI 48912 • www.lansingcitypulse.com ADVERTISING INQUIRIES: (517) 999-6704 or email [email protected] PAGE EDITOR AND PUBLISHER • Berl Schwartz 15 [email protected] • (517) 999-5061 ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER • Mickey Hirten New exhibit from 100-year-old Selma Hollander [email protected] ARTS & CULTURE EDITOR • Eve Kucharski [email protected] • (517) 999-5068 PRODUCTION MANAGER • Amanda Proscia PAGE [email protected] • (517) 999-5066 STAFF WRITERS • Lawerence Cosentino 17 [email protected] Todd Heywood Fireworks safety guide [email protected] SALES & MARKETING DIRECTOR • Rich Tupica [email protected] PAGE SALES EXECUTIVES Mandy Jackson • [email protected] Cory Hartman • [email protected] 25 Suzi Smith • [email protected] New addition to Lansing Mall food court Contributors: Andy Balaskovitz, Justin Bilicki, Daniel E. Bollman, Capital News Service, Bill Castanier, Mary C. Cusack, Tom Helma, Gabrielle Lawrence Johnson, Eve Kucharski, Terry Link, Andy McGlashen, Cover Kyle Melinn, Mark Nixon, Shawn Parker, Stefanie Pohl, Dennis Preston, Allan I. -

~ Meridian a ~ 0~~~1' ~

AGENDA ~ CHARTER TOWNSHIP OF MERIDIAN MERIDIAN A TOWNSHIP BOARD - REGULAR MEETING ~o~~s~~l; April 4, 2017 6:00 PM ~ 1. CALL MEETING TO ORDER* 2. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE/INTRODUCTIONS 3. ROLL CALL 4. PRESENTATION 5. CITIZENS ADDRESS AGENDA ITEMS AND NON-AGENDA ITEMS* 6. TOWNSHIP MANAGER REPORT A. Quarterly Report 7. BOARD MEMBER REPORTS AND ANNOUNCEMENTS 8. APPROVAL OF AGENDA 9. CONSENT AGENDA (SALMON) A. Communications B. Minutes - March 21, 2017 Regular Meeting C. Bills D. Amendment to the DDA Loan Installment Payment Schedule E. Police and Fire August Millage 2017-2026 F. Celebrate Meridian Liquor License 10. QUESTIONS FOR THE ATTORNEY 11. HEARINGS (CANARY) A. Meridian Township Brownfield Authority B. Bennett Village Phase #2 Streetlighting SAD #424 12. ACTION ITEMS (PINK) A. Rezoning #16070 (Singh) 1954 Saginaw Highway RR (Rural Residential) to RDD (Multiple Family-5 units per acre) -Final Adoption B. Rezoning# 17010 (Portnoy & Tu) north of 2476 Jolly Road from RA (Single Family-Medium Density) to PO (Professional and Office)-Introduction C. Harkness Law Firm Contract D. Sierra Ridge No. 3 Final Plat 13. BOARD DISCUSSION ITEMS (ORCHID) A. Meridian Township Brownfield Authority B. Bennett Village Phase #2 Streetlighting SAD #424 C. Recycling Center Operation Agreement 14. COMMENTS FROM THE PUBLIC* 15. OTHER MATTERS AND BOARD MEMBER COMMENTS 16. ADJOURNMENT 17. POSTSCRIPT- KATHY ANN SUNDLAND All comments limited to 3 minutes, unless prior approval for additional time for good cause is obtained from the Supervisor. Appointment of Supervisor Pro Tern and/ or Temporary Clerk if necessary. Individuals with disabilities requiring auxiliary aids or services should contact the Meridian Township Board by contacting: Township Manager Frank L. -

~ MERIDIAN a 9E ~O~~S~~Li ~ To: Board Members From: R:\L • Euann· Maisne 'R, CPRP, Director Department of Parks ~Nd Recreation

~ AGENDA MERIDIAN CHARTER TOWNSHIP OF MERIDIAN A TOWNSHIP BOARD - REGULAR MEETING ~ · JUNE 6, 2017 6:00 PM 1. CALL MEETING TO ORDERt 2. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE/INTRODUCTIONS 3. ROLL CALL 4. PRESENTATION A. Ken Plaga, Assistant Police Chief-Introduction of New Police Officer B. 2016 Township Audit-Andrew Hooper & Pavlik, PLC 5. CITIZENS ADDRESS AGENDA ITEMS AND NON-AGENDA ITEMS* 6. TOWNSHIP MANAGER REPORT 7. BOARD MEMBER REPORTS AND ANNOUNCEMENTS A. Quarterly Treasurer's Report-Julie Brixie 8. APPROVALOFAGENDA 9. CONSENT AGENDA (SALMON) A. Communications B. Minutes-May 16, 2017 Regular Meeting C. Bills D. Outdoor Gathering Permit-Gus Macker E. Outdoor Gathering Permit-Celebrate Meridian F. Summer Tax Collection Agreements G. Bennett Village Phase #2 Public Streetlighting Improvements SAD No. 424 - Resolution No. 5 10. QUESTIONS FOR THE ATTORNEY 11. HEARINGS (CANARY) 12. ACTION ITEMS (PINK) A. Commercial Planned Unit Development #17014 (Saroki), Demolish and Reconstruct Gas Station at 1619 Haslett Road B. Distributed Antennae System (DAS) C. Tank Trust Property Boundary Correction D. Urban Services Boundary E. Final Plat #05012 (Georgetown) Georgetown No.4 F. Accept 2016 Township Audit Findings G. EDC Appointment 13. BOARD DISCUSSION ITEMS (ORCHID) A. Transportation Commission Recommendations B. Mixed Use Planned Unit Development Concept Plan-2875 Northwind Drive C. 2017 Sidewalk Order to Maintain SAD #17 D. Georgetown #3 Streetlighting SAD #425 14. COMMENTS FROM THE PUBLIC* 15. OTHER MATTERS AND BOARD MEMBER COMMENTS 16. ADJOURNMENT 17. POSTSCRIPT- PATRICIA HERRING JACKSON * All comments limited to 3 minutes, unless prior approval for additional time for good cause is obtained from the Supervisor. t Appointment of Supervisor Pro Tern and/ or Temporary Clerk if necessary. -

Michigan Department of Transportation Bid Letting Results Letting of February

MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION BID LETTING RESULTS LETTING OF FEBRUARY 2, 2018 PROJECTS PENDING RELEASE The project call numbers listed below are pending release for contract award with a corresponding reason. A release date provided indicates the project is resolved. Update date: 2/22/2018; 8:45am CALL NUMBER REASON RELEASE DATE 1802 003 UBR 02/13/2018 1802 004 UBR 02/12/2018 1802 006 UBR 02/09/2018 1802 009 UBR 02/13/2018 1802 036 10% 02/22/2018 1802 055 UBR 02/09/2018 1802 059 10% 02/09/2018 1802 070 10% 02/22/2018 1802 072 10% 02/07/2018 1802 219 Other 02/14/2018-All Bids Rejected UBR-Selected for Unbalanced Bid Review Scroll down to view projects released for award. Letting of February 2, 2018 Letting Call: 1802 001 Low Bid: $1,336,750.25 Project: STUL 11000-133290 Engineer Estimate: $1,419,760.00 Local Agreement: 17-5571 Pct Over/Under Estimate: -5.85 % Start Date: June 11, 2018 Completion Date: September 7, 2018 Description: 0.48 mi of hot mix asphalt reconstruction, aggregate base, concrete curb, gutter, sidewalk and ramps, storm and sanitary sewer, drainage, machine grading, slope restoration and pavement markings on Wallace Avenue from Lakeshore Drive (BL 94) to Lakeview Avenue in the city of St. Joseph, Berrien County. This is a Local Agency Project. 4.00 % DBE participation required Bidder As-Submitted As-Checked Kalin Construction Co., Inc. $1,336,750.25 Same 1 ** Hoffman Bros., Inc. $1,428,339.40 Same 2 Kamminga & Roodvoets, Inc. -

Sunday, April 6

RED CEDAR RENAISSANCE Redevelopment of former East Side golf course could surpass $200 million | page 5 'ONE BOOK, ONE COMMUNITY' SELECTION NAMED East Lansing and MSU choose graphic novel memoir of civil rights leader | page 18 ZOOBIE’S EXPANDING Old Town bar to add wood-fired pizza extension, The Cosmos | page 23 Photo by Jeremy Daniel Photo by Jeremy SUNDAY, APRIL 6 MSU’s Wharton Center ON SALE WHARTONCENTER.COM • 1-800-WHARTON NOW! DON’T rockofagesontour.com phoenix-ent.com MISS IT! 2 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • March 19, 2014 MSU DEPARTMENT OF THEATRE WHARTONCENTER.COM OR 1-800-WHARTON PETER PAN LYRICS BY CAROLYN LEIGH, BETTY COMDEN & ADOLPH GREEN MUSIC BY MARK CHARLAP & JULE STYNE A MUSICAL BASED ON THE PLAY BY JAMES M. BARRIE APRIL 11-20, 2014 PASANT THEATRE Peter Pan is a high-flying fantasy that tells the story of the young boy who won’t grow up. This beloved musical promises a new twist on the old classic including the songs “I Won’t Grow Up,” Neverland,” and “I’ve Gotta Crow.” Join Peter, Wendy, Tinkerbell and Captain Hook as they soar over the Pasant Theatre audiences. DIRECTED BY ROB ROZNOWSKI “Peter Pan (Musical)” is presented by special arrangement with SAMUEL FRENCH, INC. City Pulse • March 19, 2014 www.lansingcitypulse.com 3 4 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • March 19, 2014 VOL. 13 Feedback ISSUE 30 ‘The Lyin’ Journal’ Facebook response to ballpark plans Back in the ‘40s, my granddad always I don't mean to be a pessimist but I have (517) 371-5600 • Fax: (517) 999-6061 • 1905 E. -

CULTURE WARS the Dark Patterns of Online Harassment

November 20 - 26, 2019 www.lansingcitypulse.com Locally owned • A newspaper for the rest of us CULTURE WARS The dark patterns of online harassment CitySee Pulse Ads.qxp_Layout page 1 11 10/27/19 4:51 PM Page 4 2 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • November 20, 2019 Benedict Auto Body Your ONE STOP shop for 246 W. Maple • Mason COLLISION, MECHANICAL & 517.676.4970 GLASS! www.benedictautobody.com FULL TIME FULLY CERTIFIED MECHANIC State Certified & Trained Computerized Auto Alignments Suspension Tune Ups Brakes “When you want AC Work quality workmanship, Exhaust Repair no mile is too far to drive.” IF YOU HIT A DEER, BRING YOUR CAR HERE! FREE LOANER CARS FOR YOU! • Be attentive from sunset to midnight and shortly before and after sunrise HAVE YOUR CAR TOWED • Drive with caution in deer-crossing zones and where roads divide agricultural fields and forest DIRECTLY TO BENEDICT • If you see one deer, there may be others nearby • Use high beams at night when there is no Save all the red tape oncoming traffic. Let us help you with your insurance • Slow down and blow your horn with a long blast to scare deer away claim • Brake firmly when a deer is in your path, but stay in your lane Personal, professional service at our • Always wear your seatbelt • Don’t rely on devices like deer whistles, deer fences and independent body shop reflectors to deter deer City Pulse • November 20, 2019 www.lansingcitypulse.com 3 Favorite Things Serving the Greater Lansing Area Since 1926 Beatles collector Viki Spector and • We are your locally owned Prescription & Compound Pharmacy and full Durable Medical Supply Retailer. -

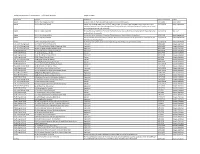

MDOT Traffic Study Summary

Michigan Department of Transportation - Traffic Study Summary August 10, 2021 Study Type Location Final Result Date Study Closed Contact Speed M-13 in the Village of Lennon Extend current 35 mph zone 600 feet south from its current location 7/17/2018 Steve Pethers Speed M-21 in the City of Lowell Revise the following speed limits on M-21: Amity Street to Hudson Street changed from 25 mph to 35 mph, 10/10/2018 Adam Vandercook Jefferson Street to James Street changed from 35 mph to 40 mph, and James Street to 0.3 miles east of James Street changed from 45 mph to 50 mph Speed M-91 in Eureka Township Change the speed limit from 45 mph to 55 mph from one mile south of the southerly limit of Greenville to the 10/10/2018 Dan Lund southerly limit of Greenville Speed M-21 in the Village of Muir Change the speed limit from 45 mph to 55 mph between Hayden Road to Hayes Road 9/20/2018 Adam Vandercook Speed M-21 in the City of Lowell Add speed limit of 40 mph between Jefferson Street and James Street and 50 mph between James Street and 10/10/2018 Adam Vandercook 0.3 mile east of James Street Parking M-79 in the Village of Nashville No Parking At Any Time allowed in the right of way of M-79 from Chapel Street to M-66 10/18/2018 Adam Vandercook Left-Turn Phasing Study M-153 (Ford Road) at Ridge Road Approved 8/13/2018 Douglas Adelman Left-Turn Phasing Study US-127 (South Meridian Road) at Jefferson Road Approved 8/15/2018 Douglas Adelman Left-Turn Phasing Study US-24 (Telegraph Road) at Newport Road Approved 8/21/2018 Douglas Adelman Traffic Signal Study