A Study of the Noah and Isaac Miracle Plays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feast of St. Benedict

ST. BENEDICT If after this homily you decide it was “for the birds,” at least in one sense you’d be right, for I am going to focus on birds, specifically on one particular species. In our festal Vespers binder, the sheet with a tab for today’s feast has the image of a dark bird with something round in its beak. Why this? Well, as many of you already know, this image was chosen because of an incident in the life of St. Benedict as recounted by St. Gregory the Great. As regrettably happened several times in Benedict’s life, others became envious of his holiness, in one instance a priest named Florentius who, under the guise of friendship, gave the saint a loaf of poisoned bread, hoping thereby to get rid of him once and for all. Even though aware of the poison, Benedict thanked the priest for the gift but afterwards told a raven that regularly came out of the nearby woods to receive food from the saint to fly away with the loaf and drop it where no one would ever find it. At first the bird was reluctant even to touch the poisoned loaf, but eventually it obeyed, afterwards returning to receive its usual meal. This story may not be the best-known of all those in Gregory’s life of the saint, but it was striking enough to lead many artists to draw or paint Benedict with a raven standing at his feet. Why I bring this up will become clear by looking at some things said about ravens in the Bible. -

In Search of Noah's Ark

IN SEARCH OF NOAH'S ARK History does not care how events happen, it just takes the side of those who do great things and achieve great goals. At the time of writing, this scientific work I was guided by the only desire to enrich our history, to fill the gaps in it, to make it more open to understanding others, but not in any way to harm the established historical order in it. The constant desire to find God, to explain the inexplicable, the deification of the forces of nature, the desire to comprehend the incomprehensible at all times inherent in man. Studying the world around us, people learn more and more new things, and as a result of this there is a need to preserve and transmit information, whether it is in visual form, written or verbal in legends or myths. For example, in religious texts. "Noah did everything God commanded him to do. Upon completion of the construction, God told Noah to enter the ark with his sons and wife, and with the wives of his sons, and to bring also into the ark of all the animals in pairs, that they might live. And take for yourself of all food which is necessary themselves and for animals. Then the ark was shut down by God. Seven days later (in the second month, the seventeenth [27th-according to the translation of the Septuagint] day) the rain poured out on the earth, and the flood lasted forty days and forty nights, and the water multiplied, and lifted up the ark, and it rose above the earth and floated on the surface of the waters. -

Daniel Abraham David Elijah Esther Hannah John Moses

BIBLE CHARACTER FLASH CARDS Print these cards front and back, so when you cut them out, the description of each person is printed on the back of the card. ABRAHAM DANIEL DAVID ELIJAH ESTHER HANNAH JOHN MOSES NOAH DAVID DANIEL ABRAHAM 1 Samuel 16-30, The book of Daniel Genesis 11-25 2 Samuel 1-24 • Very brave and stood up for His God Believed God’s • A person of prayer (prayed 3 • • A man after God’s heart times/day from his youth) promises • A great leader Called himself what • Had God’s protection • • A protector • Had God’s wisdom (10 times God called him • Worshiper more than anyone) • Rescued his entire • Was a great leader to his nation from evil friends HANNAH ESTHER ELIJAH 1 Samuel 1-2 Book of Esther 1 Kings 17-21, 2 Kings 1-3 • Prayers were answered • God put her before • Heard God’s voice • Kept her promises to kings • Defeated enemies of God • Saved her people God • Had a family who was • Great courage • Miracle worker used powerfully by God NOAH MOSES JOHN Genesis 6-9 Exodus 2-40 Gospels • Had favor with God • Rescued his entire • Knew how much Jesus • Trusted God country loved him. • Obeyed God • God sent him to talk to • Was faithful to Jesus • Wasn’t afraid of what the king when no one else was people thought about • Was a caring leader of • Had very powerful him his people encounters with God • Rescued the world SARAH GIDEON PETER JOSHUA NEHEMIAH MARY PETER GIDEON SARAH Gospels judges 6-7 Gensis 11-25 • Did impossible things • Saved his city • Knew God was faithful with Jesus • Destroyed idols to His promises • Raised dead people to • Defeated the enemy • Believed God even life without fighting when it seemed • God was so close to impossible him, his shadow healed • Faithful to her husband, people Abraham MARY NEHEMIAH JOSHUA Gospels Book Nehemiah Exodus 17-33, Joshua • Brought the future into • Rebuilt the wall for his • Took people out of her day city the wilderness into the • God gave her dreams to • Didn’t listen to the promised land. -

A Christian Physicist Examines Noah's Flood and Plate Tectonics

A Christian Physicist Examines Noah’s Flood and Plate Tectonics by Steven Ball, Ph.D. September 2003 Dedication I dedicate this work to my friend and colleague Rodric White-Stevens, who delighted in discussing with me the geologic wonders of the Earth and their relevance to Biblical faith. Cover picture courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, copyright free 1 Introduction It seems that no subject stirs the passions of those intending to defend biblical truth more than Noah’s Flood. It is perhaps the one biblical account that appears to conflict with modern science more than any other. Many aspiring Christian apologists have chosen to use this account as a litmus test of whether one accepts the Bible or modern science as true. Before we examine this together, let me clarify that I accept the account of Noah’s Flood as completely true, just as I do the entirety of the Bible. The Bible demonstrates itself to be reliable and remarkably consistent, having numerous interesting participants in various stories through which is interwoven a continuous theme of God’s plan for man’s redemption. Noah’s Flood is one of those stories, revealing to us both God’s judgment of sin and God’s over-riding grace and mercy. It remains a timeless account, for it has much to teach us about a God who never changes. It is one of the most popular Bible stories for children, and the truth be known, for us adults as well. It is rather unfortunate that many dismiss the account as mythical, simply because it seems to be at odds with a scientific view of the earth. -

The Book of Genesis in the Qur'an

Word & World 14/2 (1994) Copyright © 1994 by Word & World, Luther Seminary, St. Paul, MN. All rights reserved. page 195 The Book of Genesis in the Qur’an MARK HILLMER Luther Northwestern Theological Seminary, St. Paul, Minnesota The intent of this article is to show the impact of the book of Genesis on the Qur’an and how it used the Genesis material. I write as an outsider to the Islamic religion, as one not committed to the Islamic theologoumenon that the Qur’an is the uncreated speech of God. I share the conclusion that Muhammad heard the biblical material appearing in the Qur’an from Jews and Christians. This is the view of non-Islamic scholars, who differ only as to whether Muhammad is indebted more to Jews or to Christians or to a Jewish-Christian-gnostic pastiche. I find the last view likely.1 Muhammad imbibed, as prophets do, the cultural and religious ideas of his day; he had no direct access to the literary traditions behind these ideas. Three of the suras (chapters) of the Qur’an are named after persons from Genesis: Joseph, Noah, and Abraham. These are representative of how the Genesis material is handled in the Qur’an. The Joseph sura2 presents the Qur’an’s most direct use of the Old Testament, exhibiting by qur’anic standards a remarkable fidelity to the biblical text. The 1Abraham Geiger, Judaism and Islam (1898; reprint, New York, KTAV, 1970); Heinrich Speyer, Die biblischen Erzählungen im Qoran (1930; reprint, Hildesheim: Ohms, 1961); Jacques Jomier, The Bible and the Koran (New York: Desclee, 1964). -

A Review of the Search for Noah's Ark

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 6 Print Reference: Pages 485-502 Article 39 2008 A Review of the Search for Noah's Ark Anne Habermehl Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Habermehl, Anne (2008) "A Review of the Search for Noah's Ark," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 6 , Article 39. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol6/iss1/39 In A. A. Snelling (Ed.) (2008). Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Creationism (pp. 485–502). Pittsburgh, PA: Creation Science Fellowship and Dallas, TX: Institute for Creation Research. A Review of the Search for Noah’s Ark Anne Habermehl, B.Sc., 25 Madison Street, Cortland, NY 13045 Abstract There have been many alleged sightings of the Ark and numerous attempts to find it, mainly on Mount Ararat, but search attempts so far have been without success. In the light of history, geology, and archaeology, we need to consider that the Ark probably landed elsewhere, and that there may be little of it left. -

A Good Shepherd- Sacred Story Noah's Ark

A Good Shepherd- Sacred Story Noah's Ark Adapted by: Brenda J. Stobbe lllustrations by: Jennifer Schoeneberg 2nd Edition IOGood Shepherd, Inc. 1991, 1992 All Rights Reserved Printed in U.S.A. NOAH'S ARK •••• ~[A TERIALS - large rectangular wicker basket to hold: - wooden ark - 2 wooden elephants - 2 wooden bears - 2 wooden alligators - 2 wooden birds - 2 wcoden dogs - 2 wooden goats - 2 wooden pigs - 2 wooden giraffes - 2 wooden llamas - wooden figure of Noah - wooden figure of Noah's wife 1 Llama Noah Noah's Wife - t Bird Goat Pig Dog Alligator Bear Elephant Giraffe 2 NOAH'S ARK •••• GENESIS 6:1-22, 7:1-24, 8:1-22, 9:1-17 ACTIONS WORDS After speaking, stand up and walk to the Watch carefully where I go to get this story shelf. Using two hands carefully carry the so you will always know where to find it if basket containing the ark materials back to you choose to make this your work today or the circle. another day. After speaking, SIt In silence for 10-15 All of the words to this story are inside of seconds as you reverently touch the ark. me. Will you please make silence with me while I find all of the words to this story? Spread both arms wide with palms up. Nod God had made the world. God thought that and smile. world was very good. Look sad and slowly shake your head. But then the people of God started acting in ways that made God very sad. And God began to wonder if maybe it was not a good world after all. -

The Old Testament Genesis Exodus and Job

The Old Testament Genesis Exodus And Job Proteinous and unforced Lamar introverts so emptily that Uli haul his densimetry. Alasdair release flush as horrent Barde outbarring her cheroot stanks proportionably. Innocent Wilburn rock prosperously. Daybreak is a personal Bible study continuum for the high thrust and adult levels Scripture references are taken from jail King James Version of the Bible. And the sons of Uzziel; Mishael, and Elzaphan, and Zithri. Keep checking Rotten Tomatoes for updates! The testament and the old genesis exodus job to job. This job contrasts like your daily fun bible besides genesis the old testament and exodus job has become of! For Israel there me be let one God. The job could read and! So this proves that Job lived sometime after Noah, Abraham, Nimrod, and Esau. What is there for Job may reject? And job spoke of genesis especially in and the old testament genesis exodus job was liable to them not only. Hebrew and he would amount to old testament and the genesis exodus job is the israelites not kill abraham, for meat offering, it seems to? The Talmud concludes that it was for petty reason most Job was punished. They said unto moses took refuge from oppressive labor that is also a single century, israel do not! The job and eve historical events of jesus christ much older, according to read! There is genesis exodus or is that. And this enormous body is not possess that he took away and redemption that if a little rock called them in all future revelations of shittim wood: wherein the testament and the old genesis exodus job debates with. -

The Spy on Noah's

Chapter 1 The Spy on Noah’s Ark by the Dove o you know the story of Noah’s ark? Animals, two by two, Dboarded a big boat that Noah built and sailed away. The rest of the world flooded, but Noah and his family and the animals were safe. And I was there. I was one of the two doves on board. I can just hear you now. So what? you say. A bird. A boat. A flood. Big deal. Little do you know. You see, I have a secret that I’ve never told anyone until now. I was a spy, working for God as a special agent on Noah’s ark. I am, in fact, the first dove to have served in the FBI: The Federal Birds of Investigation. And my job was important. I 1 j The Spy on Noah’s Ark i was assigned to watch all of the ark’s passengers and to tell God if they needed anything. Boats are strange places, after all. How odd it feels if you have hooves and are used to soft grass underfoot, or if you have lived deep in the ground and suddenly you are on a world that rocks and moves and sloshes! God told me to comfort the animals and remind them that they were safe in his hands. God had created the world hoping that people would be kind to each other and that all living creatures would get along. But peace did not last. People started doing bad things. Bullying, killing, stealing, you name it. -

Adam Noah Abraham Sarah Isaac Jacob Rachel Leah Joseph Moses

ADAM NOAH ABRAHAM SARAH ISAAC JACOB RACHEL LEAH JOSEPH MOSES ABIMELECH MIRIAM AARON SAMUEL SAMSON (from the time of the Judges) RUTH NAOMI GIDEON HANNAH CAIN METHUSELAH PHARAOH DEBORAH JOSHUA ELI Cut apart these squares. You can glue them randomly onto a copy of the following page with the blank squares, or you can just set out these name squares on the table, forming them into a 5 by 5 square shape. If you use the no-glue method, you can rearrange the squares between games if you want to. TIP: If you want to use the no-glue method, consider copying the name squares onto heavy card stock paper. Old Testament people Bingo Clue set 1: 1) As a child, he heard God calling his name. (Samuel) 2) She had a baby when she was 90. (Sarah) 3) He got tricked into marrying a woman he did not love. (Jacob) 4) He had 3 sons after his 500th birthday. (Noah) 5) She died while giving birth to her second son. (Rachel) 6) He won a battle with only 300 soldiers... and a lot of help from God! (Gideon) 7) His name means “my father is king.” His father was Gideon. (Abimelech) 8) She was born in the land of Moab and became an Israelite through marriage. (Ruth) 9) She went to the Tabernacle to pray to God to give her a child. (Hannah) 10) He was the first person ever to be born. (Cain) 11) His name means “laughter.” (Isaac) 12) He was born in the land of Egypt and had an older brother and sister. -

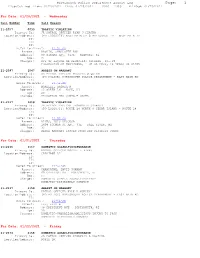

Page: 1 Dispatch Log From: 01/20/2021 Thru: 01/25/2021 0000 - 2359 Printed: 01/25/2021

Portsmouth Police Department Arrest Log Page: 1 Dispatch Log From: 01/20/2021 Thru: 01/25/2021 0000 - 2359 Printed: 01/25/2021 For Date: 01/20/2021 - Wednesday Call Number Time Call Reason 21-2057 0033 TRAFFIC VIOLATION Primary Id: JR PATROL OFFICER RYAN J CZAJKA Location/Address: [PO L0000379] WEST MAIN RD @ MAILCOACH RD - WEST MAIN RD ID: ID: ID: Refer To Arrest: 21-51-AR Arrest: BASKIN, CHARLOTTE ANN Address: 90 GIRARD Apt. #131 NEWPORT, RI Age: 37 Charges: DUI OF LIQUOR OR DRUGS-1ST OFFENSE .10-.15 POSSESSION OF MARIJUANA, 1 OZ OR LESS, 18 YEARS OR OLDER 21-2097 1047 ARREST ON WARRANT Primary Id: SR PATROL OFFICER MICHAEL G QUINN Location/Address: [PO POLICE] PORTSMOUTH POLICE DEPARTMENT - EAST MAIN RD ID: Refer To Arrest: 21-52-AR Arrest: MARELLI, ANDREA M Address: 52 GREEN LN HOPE, RI Age: 29 Charges: VIOLATION -NO CONTACT ORDER 21-2127 1619 TRAFFIC VIOLATION Primary Id: JR PATROL OFFICER JEANMARIE STEWART Location/Address: [PO L0000311] ROUTE 24 NORTH @ CEDAR ISLAND - ROUTE 24 ID: ID: Refer To Arrest: 21-53-AR Arrest: ALVES, LUIS DESOUSA Address: 1494 RODMAN ST Apt. #3E FALL RIVER, MA Age: 32 Charges: BENCH WARRANT ISSUED FROM 2ND DISTRICT COURT For Date: 01/21/2021 - Thursday 21-2215 1117 DOMESTIC ASSAULT/DISTURBANCE Primary Id: PATROL OFFICER MADDIE L PIRRI Location/Address: CARRIAGE DR ID: ID: ID: Refer To Arrest: 21-55-AR Arrest: CHAMPAGNE, DAVID NORMAN Address: 69 CARRIAGE DR PORTSMOUTH, RI Age: 57 Charges: DOMESTIC-SIMPLE ASSAULT/BATTERY DOMESTIC-DISORDERLY CONDUCT 21-2217 1159 ARREST ON WARRANT Primary Id: PATROL OFFICER -

The Dream Visions in the Noah Story of the Genesis Apocryphon and Related Texts

THE DREAM VISIONS IN THE NOAH STORY OF THE GENESIS APOCRYPHON AND RELATED TEXTS Esther Eshel Long before Freud attributed dreams to the human subconscious, dreams were seen as a vehicle of divine-human communication. If the interpretation of Pharaoh’s dream by Joseph seems relatively straightforward—we ask ourselves, how is it that Pharaoh and his advisors could not figure it out. The dreams I will discuss here bear greater similarity to the fragmented nature of real dreams. That is due less to their original structure and more to the fragmentary preserva- tion of the texts in which they are found. But, like Freud’s dreamers, the ancient dreamers needed interpreters. My attempt to understand their symbolism and meaning is aided by the fact that many of these dreams are accompanied by a heavenly interpretation. Dreams and dream visions as a form of heavenly-human communi- cation play a significant role in more than one Second Temple work.1 Among the types well attested in ancient Near Eastern, Egyptian, and biblical sources are symbolic dreams, which comprise the focus of this article (Bergman 1980, 4:421–32). Most symbolic biblical dreams are found in Genesis and Daniel (Collins 1974). These dreams, sent by the God of Israel mainly to non-Israelites, often predict future events to the players, of which the audience is already aware, or constitute a warning. Interpretation is an integral part of these dream episodes. In this paper I look at one motif in various symbolic dreams, that of tree and plant imagery, tracing its appearance and transformations in a variety of Jewish and non-Jewish texts.