Omic Secondary Panels Final Revised X

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

Alan Moore's Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics

Alan Moore’s Miracleman: Harbinger of the Modern Age of Comics Jeremy Larance Introduction On May 26, 2014, Marvel Comics ran a full-page advertisement in the New York Times for Alan Moore’s Miracleman, Book One: A Dream of Flying, calling the work “the series that redefined comics… in print for the first time in over 20 years.” Such an ad, particularly one of this size, is a rare move for the comic book industry in general but one especially rare for a graphic novel consisting primarily of just four comic books originally published over thirty years before- hand. Of course, it helps that the series’ author is a profitable lumi- nary such as Moore, but the advertisement inexplicably makes no reference to Moore at all. Instead, Marvel uses a blurb from Time to establish the reputation of its “new” re-release: “A must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” That line came from an article written by Graeme McMillan, but it is worth noting that McMillan’s full quote from the original article begins with a specific reference to Moore: “[Miracleman] represents, thanks to an erratic publishing schedule that both predated and fol- lowed Moore’s own Watchmen, Moore’s simultaneous first and last words on ‘realism’ in superhero comics—something that makes it a must-read for scholars of the genre, and of the comic book medium as a whole.” Marvel’s excerpt, in other words, leaves out the very thing that McMillan claims is the most important aspect of Miracle- man’s critical reputation as a “missing link” in the study of Moore’s influence on the superhero genre and on the “medium as a whole.” To be fair to Marvel, for reasons that will be explained below, Moore refused to have his name associated with the Miracleman reprints, so the company was legally obligated to leave his name off of all advertisements. -

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

Afraid of Bear to Zuni: Surnames in English of Native American Origin Found Within

RAYNOR MEMORIAL LIBRARIES Indian origin names, were eventually shortened to one-word names, making a few indistinguishable from names of non-Indian origin. Name Categories: Personal and family names of Indian origin contrast markedly with names of non-Indian Afraid of Bear to Zuni: Surnames in origin. English of Native American Origin 1. Personal and family names from found within Marquette University Christian saints (e.g. Juan, Johnson): Archival Collections natives- rare; non-natives- common 2. Family names from jobs (e.g. Oftentimes names of Native Miller): natives- rare; non-natives- American origin are based on objects common with descriptive adjectives. The 3. Family names from places (e.g. following list, which is not Rivera): natives- rare; non-native- comprehensive, comprises common approximately 1,000 name variations in 4. Personal and family names from English found within the Marquette achievements, attributes, or incidents University archival collections. The relating to the person or an ancestor names originate from over 50 tribes (e.g. Shot with two arrows): natives- based in 15 states and Canada. Tribal yes; non-natives- yes affiliations and place of residence are 5. Personal and family names from noted. their clan or totem (e.g. White bear): natives- yes; non-natives- no History: In ancient times it was 6. Personal or family names from customary for children to be named at dreams and visions of the person or birth with a name relating to an animal an ancestor (e.g. Black elk): natives- or physical phenominon. Later males in yes; non-natives- no particular received names noting personal achievements, special Tribes/ Ethnic Groups: Names encounters, inspirations from dreams, or are expressed according to the following physical handicaps. -

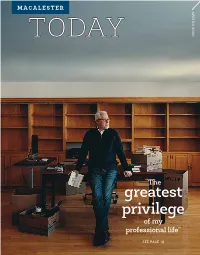

Download Issue PDF the Spring 2020 Issue of Macalester Today Is Available for Viewing In

MACALESTER SPRING 2020 TODAY “The greatest privilege of my professional life” SEE PAGE 18 MACALESTER STAFF EDITOR SPRING 2020 Rebecca DeJarlais Ortiz ’06 TODAY [email protected] ART DIRECTION The ESC Plan / theESCplan.com CLASS NOTES EDITOR Robert Kerr ’92 PHOTOGRAPHER David J. Turner CONTRIBUTING WRITER Julie Hessler ’85 ASSISTANT VICE PRESIDENT FOR MARKETING AND COMMUNICATIONS Julie Hurbanis 14 18 26 32 36 CHAIR, BOARD OF TRUSTEES Jerry Crawford ’71 PRESIDENT FEATURES DEPARTMENTS Brian Rosenberg VICE PRESIDENT FOR ADVANCEMENT New Realities 10 Points of Struggle, Correspondence 2 D. Andrew Brown The COVID-19 pandemic forced Points of Pride 26 Household Words 3 ASSISTANT VICE PRESIDENT unprecedented, and often painful, Charting Macalester’s queer history FOR ENGAGEMENT decisions at Macalester this spring. over six decades 1600 Grand 4 Katie Ladas Macalester’s next president, Open LEFT TO RIGHT: PHOTO PROVIDED; DAVID J. TURNER; PHOTO PROVIDED; LISA HANEY, TRACEY BROWN TRACEY HANEY, LISA PROVIDED; TURNER; PHOTO J. DAVID PROVIDED; PHOTO RIGHT: TO LEFT MACALESTER TODAY (Volume 108, Number 2) “I Like to Dream Big” 14 Legends of the Night 32 Pantry, and the EcoHouse is published by Macalester College. It is mailed free of charge to alumni and friends Researcher and artist Jaye Sleep experts share their best of the college four times a year. Gardiner ’11 uses comics to advice—as well as some of their Class Notes 40 Circulation is 32,000. smash stereotypes and engage own sleep practice. You Said 41 TO UPDATE YOUR ADDRESS: new scientists. Email: [email protected] Waging Peace 36 Books 43 Call: 651-696-6295 or 1-888-242-9351 Write: Alumni Engagement Office, Macalester How to Practice Medicine Two alumni collaborate to support Weddings 45 College, 1600 Grand Ave., St. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

X-Men: Age of Apocalypse Prelude Free

FREE X-MEN: AGE OF APOCALYPSE PRELUDE PDF Scott Lobdell,Jeph Loeb,Mark Waid | 264 pages | 01 Jun 2011 | Marvel Comics | 9780785155089 | English | New York, United States X-Men: Prelude to Age of Apocalypse by Scott Lobdell The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its X-Men: Age of Apocalypse Prelude packaging where packaging is applicable. Packaging should be the same as what is found in a retail store, unless the item is handmade or was packaged by the manufacturer in non-retail packaging, such as an unprinted box or plastic bag. See details for additional description. Skip to main content. About this product. New other. Make an offer:. Auction: New Other. Stock photo. Brand new: Lowest price The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Buy It Now. Add X-Men: Age of Apocalypse Prelude cart. Make Offer. Condition is Brand New. See all 3 brand new listings. About this product Product Information Legion, the supremely powerful son of Charles Xavier, wants to change the world, and he's travelled back in time to kill Magneto to do it Can the X-Men stop him, or will the world as we know it cease to exist? Additional Product Features Dewey Edition. Show X-Men: Age of Apocalypse Prelude Show Less. Add to Cart. Any Condition Any Condition. See all 13 - All listings for this product. Ratings and Reviews Write a review. Most relevant reviews. Thanks Thanks Verified purchase: Yes. Suess Beginners Book Collection by Dr. SuessHardcover 4. -

8 Redefining Zorro: Hispanicising the Swashbuckling Hero

Redefining Zorro: Hispanicising the Swashbuckling Hero Victoria Kearley Introduction Such did the theatrical trailer for The Mask of Zorro (Campbell, 1998) proclaim of Antonio Banderas’s performance as the masked adventurer, promising the viewer a sexier and more daring vision of Zorro than they had ever seen before. This paper considers this new image of Zorro and the way in which an iconic figure of modern popular culture was redefined through the performance of Banderas, and the influence of his contemporary star persona, as he became the first Hispanic actor ever to play Zorro in a major Hollywood production. It is my argument that Banderas’s Zorro, transformed from bandit Alejandro Murrieta into the masked hero over the course of the film’s narrative, is necessarily altered from previous incarnations in line with existing Hollywood images of Hispanic masculinity when he is played by a Hispanic actor. I will begin with a short introduction to the screen history of Zorro as a character and outline the action- adventure hero archetype of which he is a prime example. The main body of my argument is organised around a discussion of the employment of three of Hollywood’s most prevalent and enduring Hispanic male types, as defined by Latino film scholar, Charles Ramirez Berg, before concluding with a consideration of how these ultimately serve to redefine the character. Who is Zorro? Zorro was originally created by pulp fiction writer, Johnston McCulley, in 1919 and first immortalised on screen by Douglas Fairbanks in The Mark of Zorro (Niblo, 1920) just a year later. -

Batman Year One Proprosal by Larry and Andy

BATMAN YEAR ONE PROPROSAL BY LARRY AND ANDY WACHOWSKI The scene is Gotham City, in the past. A party is going on and from it descends Thomas Wayne with his wife Martha, and son Bruce. They are talking, with Bruce chatting away about how he wants to see The Mark of Zorro again. Obviously they have just come from a movie premiere. As they turn a corner to their car, they are met by a hooded gunman who tries holding them up. There is a struggle and the Wayne parents are murdered in a bloodbath. Bruce is left there, when he is met by a police officer. There is a screech and a bat flies overhead... Twenty years have passed. Bruce is now twenty‐eight and quite dynamic. The main character has been travelling the world, training for a war on crime, to avenge his parents' deaths. He is at the Ludlow International Airport, where his butler Alfred picks him up. The two drive to Wayne Manor, just outside of Gotham. Bruce watches the city from the distance. The scene moves to downtown Gotham, where Bruce is wearing a hockey mask and black clothes. A fight breaks out between him and a pimp which leads to Bruce escaping to a rotting building. Bleeding badly, he doesn't know whether to continue his crusade against crime. A screech fills the area and a bat dives at him, knocking him onto an old chair. Bruce realises his destiny... The opening credits feature Bruce at Wayne Manor, slamming down a hammer on scrap metal, moulding it into shape. -

Masquerade, Crime and Fiction

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more popular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and over- worked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discern- ing readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true- crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Published titles include: Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Ed Christian (editor) THE POST-COLONIAL DETECTIVE Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Lee Horsley THE NOIR THRILLER Fran Mason AMERICAN GANGSTER CINEMA From Little Caesar to Pulp Fiction Linden Peach MASQUERADE, CRIME AND FICTION Criminal Deceptions Susan Rowland FROM AGATHA CHRISTIE TO RUTH RENDELL British Women Writers in Detective and Crime Fiction Adrian Schober POSSESSED CHILD NARRATIVES IN LITERATURE AND FILM Contrary States Heather Worthington THE RISE OF THE DETECTIVE IN EARLY NINETEENTH-CENTURY POPULAR FICTION Crime Files Series Standing Order ISBN 978-0–333–71471–3 (Hardback) 978-0–333–93064–9 (Paperback) (outside North America only) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. -

Enchantress Ebook, Epub

ENCHANTRESS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Maxwell | 624 pages | 29 Jul 2014 | Amazon Publishing | 9781477823521 | English | Seattle, United States Enchantress PDF Book Who dares summon forth the Bible-black ephemeral energies of the Enchantress?! Cara Delevingne as Enchantress in Suicide Squad. Well, the June half of the character, anyway. Enjoy unlimited streaming access to original DC series with new episodes available weekly. This wiki All wikis. She was very mystical a kind of priestess, an enchantress. She turns into the Enchantress but the Enchantress ends up scheming with the demon to escape Amanda Waller and destroy the world. Free word lists and quizzes from Cambridge. June Moone lets the Enchantress out who also remains unaffected due to being a magical entity. People who perform magic or have paranormal abilities. Stepping outside, she begins channeling arcs of lightning into the sky. Her defences were formidable, easily seeing off Superman , Wonder Woman and Cyborg with a storm of old human teeth and later beating Zatanna off with a host of zombies. When mild-mannered June Moone inadvertently opened herself up to possession by a powerful magical entity known as the Enchantress, her life was forever changed. While Incubus continues to wreak havoc in the city and destroy the military's attacks against them, he also contributes to the superweapon by lifting the wreckage of buildings and destroyed military equipment to the "ring" now hovering above Midway City. Enchantress was known to have extreme pride in her status as one of the oldest living metahumans. Doorway to Nightmare Strange Adventures. Back in the '80s, writer Jack C. -

Graphic Novel Titles

Comics & Libraries : A No-Fear Graphic Novel Reader's Advisory Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives February 2017 Beginning Readers Series Toon Books Phonics Comics My First Graphic Novel School Age Titles • Babymouse – Jennifer & Matthew Holm • Squish – Jennifer & Matthew Holm School Age Titles – TV • Disney Fairies • Adventure Time • My Little Pony • Power Rangers • Winx Club • Pokemon • Avatar, the Last Airbender • Ben 10 School Age Titles Smile Giants Beware Bone : Out from Boneville Big Nate Out Loud Amulet The Babysitters Club Bird Boy Aw Yeah Comics Phoebe and Her Unicorn A Wrinkle in Time School Age – Non-Fiction Jay-Z, Hip Hop Icon Thunder Rolling Down the Mountain The Donner Party The Secret Lives of Plants Bud : the 1st Dog to Cross the United States Zombies and Forces and Motion School Age – Science Titles Graphic Library series Science Comics Popular Adaptations The Lightning Thief – Rick Riordan The Red Pyramid – Rick Riordan The Recruit – Robert Muchamore The Nature of Wonder – Frank Beddor The Graveyard Book – Neil Gaiman Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children – Ransom Riggs House of Night – P.C. Cast Vampire Academy – Richelle Mead Legend – Marie Lu Uglies – Scott Westerfeld Graphic Biographies Maus / Art Spiegelman Anne Frank : the Anne Frank House Authorized Graphic Biography Johnny Cash : I See a Darkness Peanut – Ayun Halliday and Paul Hope Persepolis / Marjane Satrapi Tomboy / Liz Prince My Friend Dahmer / Derf Backderf Yummy : The Last Days of a Southside Shorty