Review of Gender, Child, and LGBTI Asylum Guidelines and Case Law in Foreign Jurisdictions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

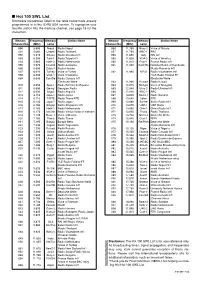

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

A Channel Guide

Intelsat is the First MEDIA Choice In Africa Are you ready to provide top media services and deliver optimal video experience to your growing audiences? With 552 channels, including 50 in HD and approximately 192 free to air (FTA) channels, Intelsat 20 (IS-20), Africa’s leading direct-to- home (DTH) video neighborhood, can empower you to: Connect with Expand Stay agile with nearly 40 million your digital ever-evolving households broadcasting reach technologies From sub-Saharan Africa to Western Europe, millions of households have been enjoying the superior video distribution from the IS-20 Ku-band video neighborhood situated at 68.5°E orbital location. Intelsat 20 is the enabler for your TV future. Get on board today. IS-20 Channel Guide 2 CHANNEL ENC FR P CHANNEL ENC FR P 947 Irdeto 11170 H Bonang TV FTA 12562 H 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11514 H Boomerang EMEA Irdeto 11634 V 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11674 H Botswana TV FTA 12634 V 1485 Radio Today Irdeto 11474 H Botswana TV FTA 12657 V 1KZN TV FTA 11474 V Botswana TV Irdeto 11474 H 1KZN TV Irdeto 11594 H Bride TV FTA 12682 H Nagravi- Brother Fire TV FTA 12562 H 1KZN TV sion 11514 V Brother Fire TV FTA 12602 V 5 FM FTA 11514 V Builders Radio FTA 11514 V 5 FM Irdeto 11594 H BusinessDay TV Irdeto 11634 V ABN FTA 12562 H BVN Europa Irdeto 11010 H Access TV FTA 12634 V Canal CVV International FTA 12682 H Ackermans Stores FTA 11514 V Cape Town TV Irdeto 11634 V ACNN FTA 12562 H CapeTalk Irdeto 11474 H Africa Magic Epic Irdeto 11474 H Capricorn FM Irdeto 11170 H Africa Magic Family Irdeto -

Download This PDF File

internet resources John H. Barnett Global voices, global visions International radio and television broadcasts via the Web he world is calling—are you listening? used international broadcasting as a method of THere’s how . Internet radio and tele communicating news and competing ideologies vision—tuning into information, feature, during the Cold War. and cultural programs broadcast via the In more recent times, a number of reli Web—piqued the interest of some educators, gious broadcasters have appeared on short librarians, and instructional technologists in wave radio to communicate and evangelize the 1990s. A decade ago we were still in the to an international audience. Many of these early days of multimedia content on the Web. media outlets now share their programming Then, concerns expressed in the professional and their messages free through the Internet, literature centered on issues of licensing, as well as through shortwave radio, cable copyright, and workable business models.1 television, and podcasts. In my experiences as a reference librar This article will help you find your way ian and modern languages selector trying to to some of the key sources for freely avail make Internet radio available to faculty and able international Internet radio and TV students, there were also information tech programming, focusing primarily on major nology concerns over bandwidth usage and broadcasters from outside the United States, audio quality during that era. which provide regular transmissions in What a difference a decade makes. Now English. Nonetheless, one of the benefi ts of with the rise of podcasting, interest in Web tuning into Internet radio and TV is to gain radio and TV programming has recently seen access to news and knowledge of perspec resurgence. -

Death by Policy

List of 33.305 documented deaths of refugees and migrants due to the restrictive policies of Fortress Europe Documentation as at 15 June 2017 by UNITED Death by Policy - Time for Change! Campaign information: Facebook - UNITED Against Refugee Deaths, UnitedAgainstRefugeeDeaths.eu, [email protected], Twitter: @UNITED__Network #AgainstRefugeeDeaths UNITED for Intercultural Action, European network against nationalism, racism, fascism and in support of migrants and refugees Postbus 413 NL-1000 AK Amsterdam phone +31-20-6834778, fax 31-20-6834582, [email protected], www.unitedagainstracism.org The UNITED List of Deaths can be freely re-used, translated and re-distributed, provided source (www.unitedagainstracism.org) is mentioned. Researchers can obtain this list with more data in xls format from UNITED. name region of origin cause of death source number found dead 29/05/2017 30 N.N. (1 small child) unknown 2 bodies found, 28 missing, drowned or trampled in panic, when boat sank off Libya VOA/USNews 27/05/2017 10 N.N. unknown drowned, during 24 hours of rescue operations between Libya and Italy, 2200 rescued DailySabah 24/05/2017 82 N.N. unknown missing, after falling into the water when their rubber boat deflated between Libya and Italy USNews 23/05/2017 34 N.N. (7 children, 13 women) unknown drowned, when boat of 500 suddenly capsized off Libya, sending 200 people into the sea DailyStar/USNews/Xinhua 22/05/2017 2 N.N. West Africa/unknown 1 drowned, 1 missing, in the Mediterranean Sea on the way to Italy IOM 22/05/2017 2 N.N. (men) unknown bodies found in Al Maya (Libya) IOM 19/05/2017 1 N.N. -

South Africa 2018/19 Communications

OFFICIAL GUIDE TO South Africa 2018/19 Communications 53 Official Guide to South Africa 2018/19 Communications 54 Department of Communications (DoC) and Digital Technologies (DCDT) Following the reconfiguration of government departments in June 2019, the DoC was merged with the Department of Telecommunications and Postal Services (DTPS) to form the new DCDT. The then DoC was spearheading the process of migrating broadcasting signals from analogue to digital. South Africa’s national digital network coverage comprises DTT transmission coverage of 84% of the population with the remaining 16% to be covered by satellite network. DTT is a reliable and cost-efficient means to distribute linear TV content and has many advantages over the analogue broadcasting system. One of its major advantages for communities is that it clears the analogue spectrum for the delivery of broadband mobile Internet and Wi-fi services. To view digital TV signals on an ordinary analogue TV set, consumers will need a set-top box (STB). Government will provide about five million poor TV-owning households with free STBs. Once the migration is complete, high definition TV telecast facilities would be available, along with expanded community, FM and satellite radio services to the entire population. During the 2017/18 financial year, the then DoC developed the White Paper on Audio-Visual and Digital Content Policy for South Africa, which provides enabling mechanisms to facilitate ownership of the new audio-visual digital content value chain by previously disadvantaged communities and small, medium and micro enterprises. Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) In 2018, Communications (and Digital Technologies) Minister Stella Ndabeni-Abrahams announced the “Building a Capable 4IR Army” capacity development programme to ensure that communities are equipped to take advantage of new digital technologies, unlock future jobs and drive competitiveness. -

Communications

Vote 26 Communications 2005/06 2006/07 2007/08 To be appropriated MTEF allocations R1 017 503 000 R1 128 951 000 R1 182 499 000 of which: Current Transfers Capital payments payments R247 141 000 R763 882 000 R6 480 000 Statutory amounts – – – Responsible minister Minister of Communications Administering department Department of Communications Accounting officer Director-General of Communications Aim The aim of the Department of Communications is to develop Information and Communication Technology (ICT) policies and legislation that stimulate and enhance the sustainable economic development of the South African 1st and 2nd economy and positively impact on the social well- being of all our people and to exercise oversight on state-owned telecommunications entities. Programme purpose and measurable objective Programme 1: Administration Purpose: Provide strategic leadership and overall management of the department, and provide professional support and administrative services. Programme 2: Strategic Policy Co-ordination and Integration Purpose: Give strategic direction to international relations, stakeholder relations, intergovernmental relations and empowerment. Measurable objective: Improve stakeholder relations and service delivery by timeously developing and co-ordinating strategic business plans. Programme 3: Policy Unit Purpose: Develop ICT and related policies that will create optimal conditions for investment and the rollout of ICT infrastructure and services, and contribute to nation-building and social cohesion to achieve sustainable economic development. Measurable objective: Promote investment and rollout of infrastructure and services in the ICT sector by continuously developing, reviewing and implementing ICT policies. Programme 4: Finance and Shareholder Management Purpose: Provide support services to stakeholders and manage government's shareholding interest in ICT related state-owned entities. -

200 8 Report T O Contribut Ors Puget Sound Public Radio

CAR TALK WEEKEND EDITION THE DIANE REHM SHOW BBC WORLD SERVICE A PRAIRIE HOME COMPANION MARKETPLACE KUOW NEWS KUOW PRESENTS WEEKDAY THE CONVERSATION SPEAKER’S FORUM SOUND FOCUS THE SWING YEARS AND BEYOND KUOW PUGET SOUND PUBLIC RADIO MORNING EDITION 2008 REPORT TO CONTRIBUTORS TO THE POINT DAY TO DAY ALL THINGS CONSIDERED AS IT HAPPENS WAIT, WAIT…DON’T TELL ME! THIS AMERICAN LIFE THE WORLD KUOW’S MISSION IS TO CREATE A MORE INFORMED PUBLIC, ONE CHALLENGED AND INVIGORATED BY A DEEPER UNDERSTANDING AND APPRECIATION OF EVENTS, IDEAS AND CULTURES. Left, Wayne C. Roth, General Manager. Right, Frank Woodruff, KUOW Puget Sound Public Radio Board President. kuow puget sound public radio board of directors Frank Woodruff, president Jennifer O’Connor, vice president Stephanie Ellis-Smith, secretary Allan Steinman, treasurer Norm Arkans, ex officio Katharine Barrett Lee Daneker Christine Deavel Nelson Dong Jon Eastlake Joan Enticknap Robert Flennaugh II Alden Garrett Steven Gilbert Arif Gursel Jany Jacob Dennis Kenny Pauline Reiter, past president Wayne Roth, ex officio Veronica Smith David Valdez Thank you to our friends Jon Bridge, Ritajean Butterworth and Sturges Dorrance (Past President), who concluded their service as KUOW Puget Sound Public Radio board members in 2007. 1 As I think about the state of public radio in general and KUOW Puget Sound Public Radio in particular, two memorable programming events come to mind. Both are examples of the power and intimacy of a well-told story. These are stories that provide local-to-global context, stories that strengthen the value of our public service, stories that define public radio. -

Proceedings of the World Summit on Television for Children. Final Report.(2Nd, London, England, March 9-13, 1998)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 433 083 PS 027 309 AUTHOR Clarke, Genevieve, Ed. TITLE Proceedings of the World Summit on Television for Children. Final Report.(2nd, London, England, March 9-13, 1998). INSTITUTION Children's Film and Television Foundation, Herts (England). PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 127p. AVAILABLE FROM Children's Film and Television Foundation, Elstree Studios, Borehamwood, Herts WD6 1JG, United Kingdom; Tel: 44(0)181-953-0844; e-mail: [email protected] PUB TYPE Collected Works - Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Children; *Childrens Television; Computer Uses in Education; Foreign Countries; Mass Media Role; *Mass Media Use; *Programming (Broadcast); *Television; *Television Viewing ABSTRACT This report summarizes the presentations and events of the Second World Summit on Television for Children, to which over 180 speakers from 50 countries contributed, with additional delegates speaking in conference sessions and social events. The report includes the following sections:(1) production, including presentations on the child audience, family programs, the preschool audience, children's television role in human rights education, teen programs, and television by kids;(2) politics, including sessions on the v-chip in the United States, the political context for children's television, news, schools television, the use of research, boundaries of children's television, and minority-language television; (3) finance, focusing on children's television as a business;(4) new media, including presentations on computers, interactivity, the Internet, globalization, and multimedia bedrooms; and (5) the future, focusing on anticipation of events by the time of the next World Summit in 2001 and summarizing impressions from the current summit. -

Sabc Timeline

SABC TIMELINE 1936 1 August the SABC is established through the Act of Parliament and the first meeting of the SABC Board of Governors. 1937 An Afrikaans radio service is established to run parallel to the English service as A and B programmes. The Broadcast House in Johannesburg is opened and remains the headquarters of the SABC until it moves to Auckland Park in 1975. 1938 The broadcaster tables its first Annual Report for the period 1 August 1936 to 31 December 1937. 1939 The SABC openly supports the World War two under the tutelage of Rene’s Caprara, who was the Director General of the SABC. 1940 The first broadcast of isiZulu, isiXhosa and Sesotho are relayed for war support. 1942 Direct broadcasts in African languages are introduced on medium wave. 1945 The ‘U Eie Keuse’ was first broadcast and until this day it’s still running on RSG. 1950 The successful story of Springbok Radio begins as the first commercial radio service, that ruled the airwaves for more than 35 years. 1952 The first market research survey is done and showed that Springbok had 632 000 adult listenership, bringing in a Million Rand worth of advertising revenue. 1953 A rediffusion service relaying the African language broadcasts is introduced to metropolitan areas and townships throughout South Africa. 1960 African language service called Radio Bantu is launched and attracted massive listener reaction, leading to the creation of Radio Zulu, Radio Xhosa and Radio Sesotho. 1961 25 December, the first FM transmission is made from the SABC tower in Johannesburg broadcasting in English, Afrikaans and Springbok radio. -

Satellite Radio Guide

SATELLITE RADIO GUIDE T` INTERNATIONAL SHORTWAVE BROADCASTERS (via satellite) By Larry Van Horn, MTAssistant Editor WRN One English to North America 0900 Radio Prague - Prague, Czech Republic (Programming in Czech) 0927 Interval signal Galaxy 5, 125 degrees West, transponder 6 (TBS) 3.820 GHz, V-Pol, audio 1000 YLE Radio Finland - Helsinki, Finland (Regional broadcasts from various subcarrier 6.80 MHz. WRN programme details can be heard at 0625, 1525 and 1955 parts of Finland in Finnish) Eastern. Program information is also available on TBS Text page 204. You can reach 1030 YLE Radio Finland - Helsinki, Finland (News in Finnish) WRN by email at online @wrn.org or through their website the internet http: /1 on at 1100 YLE Radio Finland - Helsinki, Finland (Variable programming in Finnish - www.wrn.org. Many programs can also be heard in Canada on CBC English often light music) Overnight. WRN is relayed 24 hours a day on many cable systems via the CSPAN 1200 Interval signal Audio One Network. All times are U.S. Eastern Time and all programs in English. 1300 Voice of Russia - Moscow, Russia (Russian Programming) 1400 Radio Vlaanderen International - Brussels, Belgium (Brussels Calling with ET Station Dutch programming) 0000 Radio Telefis Eireann (RTE) - Dublin, Ireland (Irish Collection) 1430 Identification tone Radio International Berne, 0100 Swiss - Switzerland 1630 Radio Austria International - Vienna, Austria (German Programming) 0130 Monday -Friday: Channel Africa Auckland Park, - South Africa 1700 Radio Budapest - Budapest, Hungary -

British DX Club

British DX Club Africa on Mediumwave and Shortwave Guide to radio stations in Africa broadcasting on mediumwave and shortwave September 2021 featuring schedules for the A21 season Africa on Mediumwave and Shortwave This guide covers mediumwave and shortwave broadcasting in Africa, as well as target broadcasts to Africa. Contents 2-36 Country-order guide to mediumwave and shortwave stations in Africa 37-40 Selected target broadcasts to Africa 41-46 Frequency-order guide to African radio stations on mediumwave Descriptions used in this guide have been taken from radio station websites and Wikipedia. This guide was last revised on 14 September 2021 The very latest edition can always be found at www.dxguides.info Compiled and edited by Tony Rogers Please send updates to: [email protected] or [email protected]. Thank you! Algeria Enterprise Nationale de Radiodiffusion Sonore The Entreprise Nationale de Radiodiffusion Sonore (ENRS, the National Sound Broadcasting Company, Algerian Radio, or Radio Algérienne) is Algeria's state-owned public radio broadcasting organisation. Formed in 1986 when the previous Algerian Radio and Television company (established in 1962) was split into four enterprises, it produces three national radio channels: Chaîne 1 in Arabic, Chaîne 2 in Berber and Chaîne 3 in French. There are also two thematic channels (Radio Culture and Radio Coran), one international station (Radio Algérie Internationale broadcasting on shortwave) and many local stations. The official languages of Algeria are Arabic and Tamazight (Berber), as specified in its constitution since 1963 for the former and since 2016 for the latter. Berber has been recognised as a "national language" by constitutional amendment since 8 May 2002. -

Channel Africa Year End Lunch by Lerato Phoofolo

Editor’s Note GM’s Note News • South Africa hosts the second summit of the Forum on China-Africa (FOCAC) by Milton Maluleque. Events/Achievements • Fun Walk by Joe Manciya. • Channel Africa Year End Lunch by Lerato Phoofolo. Feature • Fusing the old with the new (Rachel Makhura and Ntswaki Charlotte Mathoka). Matters • New Appointment (Igega-Chacell Lurhakwa Bahati) • Birthdays (Jan’ & Feb’ Babies) Contributions: Editor: Mamolefe Segakweng Main Contributor and compiler: Lerato Phoofolo Edition Contributors: - Lerato Phoofolo - Joe Manciya - Milton Maluleque Layout / Design: Neo Bogoshi Brought to you by Channel Africa Communications Channel Africa is an International Radio Service of the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC). The broadcast product is designed to address the station’s vision, which is “To be the Voice of the African Renaissance”. Our mission statement is to produce and broadcast innovative and dynamic programming that informs, educates, entertains and empowers African citizens. The programming mix covers amongst others, the areas of Governance, Health, Socio-Economics, Politics, Human interest and Environment. The station’s broadcast is carried on multi platform, i.e Shortwave, Satellite, Internet and DSTV. The station broadcasts in six (6) African languages, which are English, French, Portuguese, Kiswahili, Chinyanja and Silozi. As part of information integration and empowerment, Channel Africa is partnering with other broadcasters in the continent with the aim of exchanging programmes, staff and skills. Contact us on: Address: SABC Radio Park, Cnr Henley & Artillery Roads, Auckland Park P.O Box 91313, Auckland Park, 2006, South Africa Marketing & Communications: • Email: [email protected] • Fax +27 (0)11 714 4088 • Tel: +27(0)11 414 2014 To listen live and on demand, go to: www.channelafrica.co.za Catch us and follow us on: 50 and still going This is a BIG year for the station as it marks the at Channel Africa.