Understanding Editorial Independence and Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LOCAL NEWS IS a PUBLIC GOOD Public Pathways for Supporting Coloradans’ Civic News and Information Needs in the 21St Century

LOCAL NEWS IS A PUBLIC GOOD Public Pathways for Supporting Coloradans’ Civic News and Information Needs in the 21st Century INTRODUCTION A free and independent press was so fundamental to the founding vision of “Congress shall make no law democratic engagement and government accountability in the United States that it is called out in the First Amendment to the Constitution alongside individual respecting an establishment of freedoms of speech, religion, and assembly. Yet today, local newsrooms and religion, or prohibiting the free their ability to fulfill that lofty responsibility have never been more imperiled. At exercise thereof; or abridging the very moment when most Americans feel overwhelmed and polarized by a the freedom of speech, or of the barrage of national news, sensationalism, and social media, Colorado’s local news outlets – which are still overwhelmingly trusted and respected by local residents – press; or the right of the people are losing the battle for the public’s attention, time, and discretionary dollars.1 peaceably to assemble, and to What do Colorado communities lose when independent local newsrooms shutter, petition the Government for a cut staff, merge, or sell to national chains or investors? Why should concerned redress of grievances.” citizens and residents, as well as state and local officials, care about what’s happening in Colorado’s local journalism industry? What new models might First Amendment, U.S. Constitution transform and sustain the most vital functions of a free and independent Fourth Estate: to inform, equip, and engage communities in making democratic decisions? 1 81% of Denver-area adults say the local news media do very well to fairly well at keeping them informed of the important news stories of the day, 74% say local media report the news accurately, and 65% say local media cover stories thoroughly and provide news they use daily. -

M F Global Media Philanthropy

M F Global Media Philanthropy What Funders Need to Know About Data, Trends and Pressing Issues Facing the Field March 2019 MEDIA By Sarah Armour-Jones & Jessica Clark, IMPACT Consultants to Media Impact Funders FUNDERS Research and editorial support provided by Laura Schwartz-Henderson. Published in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 2019 by Media Impact Funders. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/us/ Or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. Individuals are encouraged to cite this report and its contents. In doing so, please include the following attribution: Global Media Philanthropy: What Funders Need to Know About Data, Trends and Pressing Issues Facing the Field, by Sarah Armour-Jones and Jessica Clark, March 2019. Questions? [email protected] Want to go deeper? We’ve embedded links throughout the PDF version of this report, available online at mediaimpactfunders.org/our-work/reports/. You’ll find them if you hover over the text. Find something interesting in this report that you’d like to share? Find us on Twitter @MediaFunders Media Impact Funders 200 W. Washington Square, Suite 220 Philadelphia, PA 19128 215-574-1322 mediaimpactfunders.org Acknowledgements We’d like to thank Candid (formerly the Foundation Center and GuideStar) for creating our media grants data map and for making their data available. This report was produced with support from the Bill & -

Reporting Facts: Free from Fear Or Favour

Reporting Facts: Free from Fear or Favour PREVIEW OF IN FOCUS REPORT ON WORLD TRENDS IN FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND MEDIA DEVELOPMENT INDEPENDENT MEDIA PLAY AN ESSENTIAL ROLE IN SOCIETIES. They make a vital contribution to achieving sustainable development – including, topically, Sustainable Development Goal 3 that calls for healthy lives and promoting well-being for all. In the context of COVID-19, this is more important than ever. Journalists need editorial independence in order to be professional, ethical and serve the public interest. But today, journalism is under increased threat as a result of public and private sector influence that endangers editorial independence. All over the world, journalists are struggling to stave off pressures and attacks from both external actors and decision-making systems or individuals in their own outlets. By far, the greatest menace to editorial independence in a growing number of countries across the world is media capture, a form of media control that is achieved through systematic steps by governments and powerful interest groups. This capture is through taking over and abusing: • regulatory mechanisms governing the media, • state-owned or state-controlled media operations, • public funds used to finance journalism, and • ownership of privately held news outlets. Such overpowering control of media leads to a shrinking of journalistic autonomy and contaminates the integrity of the news that is available to the public. However, there is push-back, and even more can be done to support editorial independence -

Who Owns the News Media?

RESEARCH REPORT July 2016 WHO OWNS THE NEWS MEDIA? A study of the shareholding of South Africa’s major media companies ANALYSTS: Stuart Theobald, CFA Colin Anthony PhibionMakuwerere, CFA www.intellidex.co.za Who Owns the News Media ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We approached all of the major media companies in South Africa for assistance with information about their ownership. Many responded, and we are extremely grateful for their efforts. We also consulted with several academics regarding previous studies and are grateful to Tawana Kupe at Wits University for guidance in this regard. Finally, we are grateful to Times Media Group who provided a small budget to support the research time necessary for this project. The findings and conclusions of this project are entirely those of Intellidex. COPYRIGHT © Copyright Intellidex (Pty) Ltd This report is the intellectual property of Intellidex, but may be freely distributed and reproduced in this format without requiring permission from Intellidex. DISCLAIMER This report is based on analysis of public documents including annual reports, shareholder registers and media reports. It is also based on direct communication with the relevant companies. Intellidex believes that these sources are reliable, but makes no warranty whatsoever as to the accuracy of the data and cannot be held responsible for reliance on this data. DECLARATION OF CONFLICTS Intellidex has, or seeks to have, business relationships with the companies covered in this report. In particular, in the past year, Intellidex has undertaken work and received payment from, Times Media Group, Independent Newspapers, and Moneyweb. 2 www.intellidex.co.za © Copyright Intellidex (Pty) Ltd Who Owns the News Media CONTENTS 1. -

A Brief History of Radio Broadcasting in Africa

A Brief History of Radio Broadcasting in Africa Radio is by far the dominant and most important mass medium in Africa. Its flexibility, low cost, and oral character meet Africa's situation very well. Yet radio is less developed in Africa than it is anywhere else. There are relatively few radio stations in each of Africa's 53 nations and fewer radio sets per head of population than anywhere else in the world. Radio remains the top medium in terms of the number of people that it reaches. Even though television has shown considerable growth (especially in the 1990s) and despite a widespread liberalization of the press over the same period, radio still outstrips both television and the press in reaching most people on the continent. The main exceptions to this ate in the far south, in South Africa, where television and the press are both very strong, and in the Arab north, where television is now the dominant medium. South of the Sahara and north of the Limpopo River, radio remains dominant at the start of the 21St century. The internet is developing fast, mainly in urban areas, but its growth is slowed considerably by the very low level of development of telephone systems. There is much variation between African countries in access to and use of radio. The weekly reach of radio ranges from about 50 percent of adults in the poorer countries to virtually everyone in the more developed ones. But even in some poor countries the reach of radio can be very high. In Tanzania, for example, nearly nine out of ten adults listen to radio in an average week. -

Rfi/It/2019/9 Sabc Digital Streaming Services

Tender Number: RFI/IT/2019/9 Title: REQUEST FOR INFORMATION: FOR SABC DIGITAL STREAMING SERVICES do REQUEST FOR INFORMATION REQUEST FOR INFORMATION TITLE: RFI/IT/2019/9 SABC DIGITAL STREAMING SERVICES This Request for Information calls for SABC Digital Streaming Services. RFI documents are obtainable from 26th April 2019 from the following websites: Government E-Portal http://www.etenders.gov.za SABC Website http://www.sabc.co.za/sabc/tenders Compulsory Briefing Session will be held Date: 10th May 2019 Time: 11:15 Venue: SABC Radio Park, Ground Floor Auditorium Closing Date: 27th May 2019at 12:00 For enquiries contact Vuyi Manentsa E-mail: [email protected] This RFI is an invitation for person(s) to submit information(s) for the provision of the services as set out in the specification contained herein. Accordingly, this RFI must not be construed, interpreted, or relied upon, whether expressly or implicitly, as an offer capable of acceptance by any person(s), or as creating any form of contractual, promissory or other rights. No binding contract or other understanding for the supply of services will exist between SABC and the respondent. Confidential and Proprietary Information Page 1 of 10 RFI Document Tender Number: RFI/IT/2019/9 Title: REQUEST FOR INFORMATION: FOR SABC DIGITAL STREAMING SERVICES doc SOUTH AFRICAN BROADCASTING SABC SOC LIMITED (“the SABC”) REQUEST FOR INFORMATION (RFI) RFI NUMBER : RFI/IT/2019/9 RFP TITLE : REQUEST FOR INFORMATION: FOR SABC DIGITAL STREAMING SERVICES EXPECTED TIMEFRAME RFI PROCESS EXPECTED DATES RFI Advertisement Date 26th May 2019 RFI document can be accessed on EPortal & RFI Available from SABC Website Compulsory Briefing Session Date & 10th May 2019 @ 11:15 Time Venue for Briefing Session SABC Radio Park, Ground Floor Auditorium RFI Closing Date and Time 27th May 2019 at 12:00 Delivery Venue SABC RADIO PARK Vuyi Manentsa E-mail: [email protected] Contact details The SABC retains the right to change the timeframe whenever necessary and for whatever reason it deems fit. -

Dynamics of Competition in Two-Sided Markets with Differentiated Products: a Case Study of the Radio Industry Following the Primedia/New Africa Investment Ltd Merger

Work in progress, not for citation purposes Dynamics of competition in two-sided markets with differentiated products: A case study of the radio industry following the Primedia/New Africa Investment Ltd merger Rantao Itumeleng1 Abstract The decision by the Competition Tribunal to unconditionally approve the Primedia/New Africa Investment Limited merger case (NAIL) is the subject of this paper. This study conducts an impact assessment of the Primedia/NAIL case. It does so using market definition as the first step in the assessment of competition in the Gauteng commercial radio industry. In markets with two different groups of customers, repositioning is fundamental in the assessment of anticompetitive effects post-merger. Utilizing tools identified in literature and international cases, the study adopts an ex post approach to assess competition in the Gauteng commercial radio industry. Findings indicate that in mergers that do not lead to join control, merging firms’ stations reposition away. Highveld and Kaya repositioned away from each other post-merger. Because of this dynamic nature of radio as well as the structure of the market in Gauteng, no effective competitors to Kaya and Highveld in the relevant market, Highveld and Kaya’s prices rose faster than other radio stations’ prices post-merger. At an industry level, competition also deteriorated post-merger as prices rose significantly mainly because of few sales house. These findings imply that the initial decision by the Competition Tribunal to approve the merger unconditionally may be incorrect. Keywords: Unilateral effects, coordinated effects, Repositioning, Partial acquisition 1. Introduction Prior to 1978, radio was the leading electronic medium in South Africa before being surpassed by television (Competition Commission, 2006:1). -

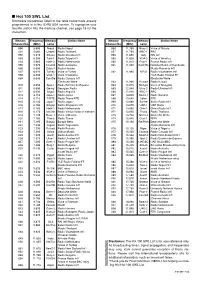

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

SABC July/August 2021 Packages in Celebration of Mandela Month XK FM 26 Breakfast Sports Show - 4 Weeks 26

SABC July/August 2021 Packages In Celebration of Mandela Month XK FM 26 Breakfast Sports Show - 4 Weeks 26 MOTSWEDING FM 27 Covid-19 Update 27 Family Health 28 Auto Feature 29 Legal, Finance & Consumer 30 contentsSABC 1 4 Movies SABC 1- Friday July @ 21h00 4 LESEDI FM 31 Movies SABC 1- Saturday July @ 20h00 5 Business Tuesdays 31 Movies SABC 1- Sunday July @ 21h00 6 Healthy Lifestyle 32 SABC 1 SHOWS - 18h00 Block 7 Diy 33 SABC 1 SHOWS - 19h30 Block 8 Transport News 34 Monthly Package 18h00-19h30 Squeeze-back and Commercial 9 Monthly Package 18h00-19h30 Squeeze-back and Commercial 10 IKWEKWEZI FM 35 Monthly Package 19h30 Tops and tails 11 National Savings Month - 4 Weeks 35 Monthly Package 18h00-19h30 Tops and tails 12 Umma Wamambala – Woman Crush Wednesday - 13 Weeks 36 Standard Terms and Conditions 13 LIGWALAGWALA FM 37 National Savings Month - 4 Weeks 37 PHALAPHALA FM 15 Business101 - 13 Weeks 38 Uplifting Vhembe Villages/Midi Na Midanani - 5 Weeks 15 Ariphalalane/Let’s Rescue Each Other - 4 Weeks 16 RADIO 2000 39 The Glenzito Super Drive 39 THOBELA FM 17 Re Go Thusha Ka Eng” / How Can We Help You - 5 Weeks 17 SAFM 40 I Am Leader (Ke Moetapele) - 5 Weeks 18 Life Happens 40 Fighting Covid With Prayer (Re Lwantšha Covid Ka Thapelo) - 4 Weeks 19 METRO FM 41 The Metro Fm Top 40 - 8 Weeks 41 MUNGHANA LONENE FM 20 Uplifting Small Local Businesses / Pfuka Uti Endlela - 5 Weeks 20 UKHOZI FM 42 Women In Business / A Hi Tshami Hi Mavoko - 4 Weeks 21 Sigiya Ngengoma - 8 Weeks 42 Round Table Discussion On Gbv With Stakeholders/Survivors 22 Round Table Discussion On Gbv With Stakeholders/Survivors 23 TRU FM 43 Mandela’s Memorable Moments 24 Trufm Top 30 - 8 Weeks 43 RSG 25 Standard Terms and Conditions 44 Praatsaam - 1 Week 25 Intro The month of July is celebrated worldwide and in South Africa as Nelson Mandela Month. -

A Channel Guide

Intelsat is the First MEDIA Choice In Africa Are you ready to provide top media services and deliver optimal video experience to your growing audiences? With 552 channels, including 50 in HD and approximately 192 free to air (FTA) channels, Intelsat 20 (IS-20), Africa’s leading direct-to- home (DTH) video neighborhood, can empower you to: Connect with Expand Stay agile with nearly 40 million your digital ever-evolving households broadcasting reach technologies From sub-Saharan Africa to Western Europe, millions of households have been enjoying the superior video distribution from the IS-20 Ku-band video neighborhood situated at 68.5°E orbital location. Intelsat 20 is the enabler for your TV future. Get on board today. IS-20 Channel Guide 2 CHANNEL ENC FR P CHANNEL ENC FR P 947 Irdeto 11170 H Bonang TV FTA 12562 H 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11514 H Boomerang EMEA Irdeto 11634 V 1 Magic South Africa Irdeto 11674 H Botswana TV FTA 12634 V 1485 Radio Today Irdeto 11474 H Botswana TV FTA 12657 V 1KZN TV FTA 11474 V Botswana TV Irdeto 11474 H 1KZN TV Irdeto 11594 H Bride TV FTA 12682 H Nagravi- Brother Fire TV FTA 12562 H 1KZN TV sion 11514 V Brother Fire TV FTA 12602 V 5 FM FTA 11514 V Builders Radio FTA 11514 V 5 FM Irdeto 11594 H BusinessDay TV Irdeto 11634 V ABN FTA 12562 H BVN Europa Irdeto 11010 H Access TV FTA 12634 V Canal CVV International FTA 12682 H Ackermans Stores FTA 11514 V Cape Town TV Irdeto 11634 V ACNN FTA 12562 H CapeTalk Irdeto 11474 H Africa Magic Epic Irdeto 11474 H Capricorn FM Irdeto 11170 H Africa Magic Family Irdeto -

Download This PDF File

internet resources John H. Barnett Global voices, global visions International radio and television broadcasts via the Web he world is calling—are you listening? used international broadcasting as a method of THere’s how . Internet radio and tele communicating news and competing ideologies vision—tuning into information, feature, during the Cold War. and cultural programs broadcast via the In more recent times, a number of reli Web—piqued the interest of some educators, gious broadcasters have appeared on short librarians, and instructional technologists in wave radio to communicate and evangelize the 1990s. A decade ago we were still in the to an international audience. Many of these early days of multimedia content on the Web. media outlets now share their programming Then, concerns expressed in the professional and their messages free through the Internet, literature centered on issues of licensing, as well as through shortwave radio, cable copyright, and workable business models.1 television, and podcasts. In my experiences as a reference librar This article will help you find your way ian and modern languages selector trying to to some of the key sources for freely avail make Internet radio available to faculty and able international Internet radio and TV students, there were also information tech programming, focusing primarily on major nology concerns over bandwidth usage and broadcasters from outside the United States, audio quality during that era. which provide regular transmissions in What a difference a decade makes. Now English. Nonetheless, one of the benefi ts of with the rise of podcasting, interest in Web tuning into Internet radio and TV is to gain radio and TV programming has recently seen access to news and knowledge of perspec resurgence. -

The Development of a Business Model for a Community Radio Station

Developing a business model for a community radio station in Port Elizabeth: A case study. By Anthony Thamsanqa “Delite” Ngcezula Student no: 20531719 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in Business Administration at the NMMU Business School Research supervisor: Dr Margaret Cullen November, 2008 DECLARATION BY STUDENT FULL NAME: Anthony Thamsanqa “Delite” Ngcezula STUDENT NUMBER: 20531719 QUALIFICATION: Masters in Business Administration DECLARATION: In accordance with Rule G4.6.3, I hereby declare that this treaties with a title “Developing a business model for a community radio station in Port Elizabeth: A case study” is my own work and that it has not previously been submitted for assessment to another University or for another qualification. SIGNITURE: __________________________ DATE: ________________________ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude and thanks to my research supervisor, Doctor Margaret Cullen, whose academic guidance and encouragement was invaluable. I wish to thank Kingfisher FM as without their cooperation this treatise would not have been possible. I would like to thank my wife, Spokazi for putting up with the long hours I spent researching and writing this treatise. I wish to thank my girls, Litha and Gcobisa for their unconditional love. I would like to thank my parents, Gladys and Wilson for the values they instilled in me. I wish to thank the following people who made listening to radio an experience and inspired my love for radio presenting and