Arxiv:Hep-Th/9411028V1 4 Nov 1994

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Conformal Field Theory and String

SLAC-PUB-5149 December 1989 m INTRODUCTION TO CONFORMAL FIELD THEORY AND STRING THEORY* Lance J. Dixon Stanford Linear Accelerator Center Stanford University Stanford, CA 94309 ABSTRACT I give an elementary introduction to conformal field theory and its applications to string theory. I. INTRODUCTION: These lectures are meant to provide a brief introduction to conformal field -theory (CFT) and string theory for those with no prior exposure to the subjects. There are many excellent reviews already available (or almost available), and most of these go in to much more detail than I will be able to here. Those reviews con- centrating on the CFT side of the subject include refs. 1,2,3,4; those emphasizing string theory include refs. 5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 I will start with a little pre-history of string theory to help motivate the sub- ject. In the 1960’s it was noticed that certain properties of the hadronic spectrum - squared masses for resonances that rose linearly with the angular momentum - resembled the excitations of a massless, relativistic string.14 Such a string is char- *Work supported in by the Department of Energy, contract DE-AC03-76SF00515. Lectures presented at the Theoretical Advanced Study Institute In Elementary Particle Physics, Boulder, Colorado, June 4-30,1989 acterized by just one energy (or length) scale,* namely the square root of the string tension T, which is the energy per unit length of a static, stretched string. For strings to describe the strong interactions fi should be of order 1 GeV. Although strings provided a qualitative understanding of much hadronic physics (and are still useful today for describing hadronic spectra 15 and fragmentation16), some features were hard to reconcile. -

Achievements, Progress and Open Questions in String Field Theory Strings 2021 ICTP-SAIFR, S˜Ao Paulo June 22, 2021

Achievements, Progress and Open Questions in String Field Theory Strings 2021 ICTP-SAIFR, S˜ao Paulo June 22, 2021 Yuji Okawa and Barton Zwiebach 1 Achievements We consider here instances where string field theory provided the answer to physical open questions. • Tachyon condensation, tachyon vacuum, tachyon conjectures The tachyon conjectures (Sen, 1999) posited that: (a) The tachyon potential has a locally stable minimum, whose energy density measured with respect to that of the unstable critical point, equals minus the tension of the D25-brane (b) Lower-dimensional D-branes are solitonic solutions of the string theory on the back- ground of a D25-brane. (c) The locally stable vacuum of the system is the closed string vac- uum; it has no open string excitations exist. Work in SFT established these conjectures by finding the tachyon vac- uum, first numerically, and then analytically (Schnabl, 2005). These are non-perturbative results. 2 • String field theory is the first complete definition of string pertur- bation theory. The first-quantized world-sheet formulation of string theory does not define string perturbation theory completely: – No systematic way of dealing with IR divergences. – No systematic way of dealing with S-matrix elements for states that undergo mass renormalization. Work of A. Sen and collaborators demonstrating this: (a) One loop-mass renormalization of unstable particles in critical string theories. (b) Fixing ambiguities in two-dimensional string theory: For the one- instanton contribution to N-point scattering amplitudes there are four undetermined constants (Balthazar, Rodriguez, Yin, 2019). Two of them have been fixed with SFT (Sen 2020) (c) Fixing the normalization of Type IIB D-instanton amplitudes (Sen, 2021). -

Chapter 9: the 'Emergence' of Spacetime in String Theory

Chapter 9: The `emergence' of spacetime in string theory Nick Huggett and Christian W¨uthrich∗ May 21, 2020 Contents 1 Deriving general relativity 2 2 Whence spacetime? 9 3 Whence where? 12 3.1 The worldsheet interpretation . 13 3.2 T-duality and scattering . 14 3.3 Scattering and local topology . 18 4 Whence the metric? 20 4.1 `Background independence' . 21 4.2 Is there a Minkowski background? . 24 4.3 Why split the full metric? . 27 4.4 T-duality . 29 5 Quantum field theoretic considerations 29 5.1 The graviton concept . 30 5.2 Graviton coherent states . 32 5.3 GR from QFT . 34 ∗This is a chapter of the planned monograph Out of Nowhere: The Emergence of Spacetime in Quantum Theories of Gravity, co-authored by Nick Huggett and Christian W¨uthrich and under contract with Oxford University Press. More information at www.beyondspacetime.net. The primary author of this chapter is Nick Huggett ([email protected]). This work was sup- ported financially by the ACLS and the John Templeton Foundation (the views expressed are those of the authors not necessarily those of the sponsors). We want to thank Tushar Menon and James Read for exceptionally careful comments on a draft this chapter. We are also grateful to Niels Linnemann for some helpful feedback. 1 6 Conclusions 35 This chapter builds on the results of the previous two to investigate the extent to which spacetime might be said to `emerge' in perturbative string the- ory. Our starting point is the string theoretic derivation of general relativity explained in depth in the previous chapter, and reviewed in x1 below (so that the philosophical conclusions of this chapter can be understood by those who are less concerned with formal detail, and so skip the previous one). -

String Field Theory, Nucl

1 String field theory W. TAYLOR MIT, Stanford University SU-ITP-06/14 MIT-CTP-3747 hep-th/0605202 Abstract This elementary introduction to string field theory highlights the fea- tures and the limitations of this approach to quantum gravity as it is currently understood. String field theory is a formulation of string the- ory as a field theory in space-time with an infinite number of massive fields. Although existing constructions of string field theory require ex- panding around a fixed choice of space-time background, the theory is in principle background-independent, in the sense that different back- grounds can be realized as different field configurations in the theory. String field theory is the only string formalism developed so far which, in principle, has the potential to systematically address questions involv- ing multiple asymptotically distinct string backgrounds. Thus, although it is not yet well defined as a quantum theory, string field theory may eventually be helpful for understanding questions related to cosmology arXiv:hep-th/0605202v2 28 Jun 2006 in string theory. 1.1 Introduction In the early days of the subject, string theory was understood only as a perturbative theory. The theory arose from the study of S-matrices and was conceived of as a new class of theory describing perturbative interactions of massless particles including the gravitational quanta, as well as an infinite family of massive particles associated with excited string states. In string theory, instead of the one-dimensional world line 1 2 W. Taylor of a pointlike particle tracing out a path through space-time, a two- dimensional surface describes the trajectory of an oscillating loop of string, which appears pointlike only to an observer much larger than the string. -

Exceptional Field Theory and Supergravity Arnaud Baguet

Exceptional Field Theory and Supergravity Arnaud Baguet To cite this version: Arnaud Baguet. Exceptional Field Theory and Supergravity. High Energy Physics - Experiment [hep-ex]. Université de Lyon, 2017. English. NNT : 2017LYSEN022. tel-01563063 HAL Id: tel-01563063 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01563063 Submitted on 17 Jul 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Numéro National de Thèse : 2017LYSEN022 Thèse de Doctorat de l’Université de Lyon opérée par l’École Normale Supérieure de Lyon École Doctorale 52 École Doctorale de Physique et d’Astrophysique de Lyon Soutenue publiquement le 30/06/2017, par : Arnaud Baguet Exceptional Field Theory and Supergravity - Théorie des Champs Exceptionnels et Supergravité Devant le jury composé de : Martin Cederwall Chalmers University of Technology Rapporteur François Delduc École Normale Supérieure de Lyon Examinateur Axel Kleinschmidt Max Planck Institute Postdam Rapporteur Michela Petrini Université Pierre et Marie Curie Examinatrice Henning Samtleben École Normale Supérieure de Lyon Directeur Contents 1 Introduction 9 1.1 String theory, dualities and supergravity . 11 1.2 The bosonic string . 13 1.3 Compactification and T-duality . 18 1.4 Double Field Theory . 21 1.5 Exceptional Field Theory . -

String Theory and the Ads/CFT Correspondence

String Theory and the AdS/CFT correspondence Matthias Gaberdiel ETH Zürich PSI 26 September 2019 Generalities What string theory is (and what it is not)? It is a promising approach towards a quantum theory incorporating high energy physics and general relativity. However, it is not a `complete’ theory: there are many conceptual problems (in particular its off-shell formulation) that are not well understood. Generalities What string theory is (and what it is not)? There are also (mainly technical) problems in understanding string theory for time-dependent and cosmological configurations, in particular for de Sitter backgrounds. On the other hand, string theory seems to provide, for example, a convincing explanation of black hole entropy in terms of microscopic states (at least for certain black holes). Generalities What string theory is (and what it is not)? String theory makes very specific and testable predictions… However, as for any theory of quantum gravity, these predictions are only `sharp’ near the Planck scale, and direct experimental verification seems currently out of reach. Generalities As a consequence, supporting evidence for string theory has appeared more indirectly, e.g. ‣ AdS/CFT correspondence has led to testable insights into conventional QFTs ‣ Triggered new developments in mathematics, e.g. mirror symmetry. ‣ Inspiration for model building, e.g. higher dimensions, supersymmetry, etc. ‣ Given rise to new techniques for perturbative and non-perturbative analysis of (susy) QFTs, e.g. Seiberg-Witten, etc. Generalities As a consequence, supporting evidence for string theory has appeared more indirectly, e.g. ‣ AdS/CFT correspondence has led to testable insights into conventional QFTs ‣ Triggered new developments in mathematics, e.g. -

Comments on Entanglement Entropy in String Theory Arxiv:1801.03517

Comments on Entanglement Entropy in String Theory Vijay Balasubramanian1,2 and Onkar Parrikar1 1David Rittenhouse Laboratory, University of Pennsylvania, 209 S.33rd Street, Philadelphia PA, 19104, U.S.A. 2Theoretische Natuurkunde, Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), and International Solvay Institutes, Pleinlaan 2, B-1050 Brussels, Belgium. January 29, 2018 Abstract Entanglement entropy for spatial subregions is difficult to define in string theory because of the extended nature of strings. Here we propose a definition for Bosonic open strings using the framework of string field theory. The key difference (compared to ordinary quantum field theory) is that the subregion is chosen inside a Cauchy surface in the \space of open string configurations”. We first present a simple calculation of this entanglement entropy in free light-cone string field theory, ignoring subtleties related to the factorization of the Hilbert space. We reproduce the answer expected from an effective field theory point of view, namely a sum over the one-loop entanglement entropies corresponding to all the particle-excitations of the string, and further show arXiv:1801.03517v2 [hep-th] 26 Jan 2018 that the full string theory regulates ultraviolet divergences in the entanglement entropy. We then revisit the question of factorization of the Hilbert space by analyzing the covariant phase-space associated with a subregion in Witten's covariant string field theory. We show that the pure gauge (i.e., BRST exact) modes in the string field become dynamical at the entanglement cut. Thus, a proper definition of the entropy must involve an extended Hilbert space, with new stringy edge modes localized at the entanglement cut. -

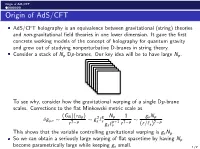

Origin of Ads/CFT Origin of Ads/CFT

Origin of AdS/CFT Origin of AdS/CFT AdS/CFT holography is an equivalence between gravitational (string) theories and non-gravitational field theories in one lower dimension. It gave the first concrete working models of the concept of holography for quantum gravity and grew out of studying nonperturbative D-branes in string theory. Consider a stack of Np Dp-branes. Our key idea will be to have large Np. To see why, consider how the gravitational warping of a single Dp-brane scales. Corrections to the flat Minkowski metric scale as (GN )(τDp) 2 8 Np 1 gs Np δgµν ∼ 7−p ∼ gs `s p+1 7−p ∼ 7−p r gs `s r (r=`s ) This shows that the variable controlling gravitational warping is gs Np. So we can obtain a seriously large warping of flat spacetime by having Np become parametrically large while keeping gs small. 1 / 7 Origin of AdS/CFT Maldacena's decoupling limit Spacetime warping can be thought of as physics of closed strings. After all, the lowest state of excitation of a closed superstring includes the graviton mode. We can also look at the open string picture of Dp-brane physics. Lowest mode of open superstring has spin-one and mass zero. Theory living 0 on worldvolume of N Dp-branes is SYMp+1 + α corrections + gs corrections. The variable controlling open string corrections when D-branes are present is actually gs Np, which is exactly what we found also controls spacetime warping. In general, dynamics of the full closed + open string sectors is unknown (c.f. -

D-Branes and Closed String Field Theory

D-branes and Closed String Field Theory N. Ishibashi (University of Tsukuba) In collaboration with Y. Baba(Tsukuba) and K. Murakami(KEK) JHEP 05(2006):029 JHEP 05(2007):020 JHEP 10(2007):008 理研シンポジウム「弦の場の理論07」 Oct. 7, 2007 1 §1 Introduction D-branes in string field theory • D-branes can be realized as soliton solutions in open string field theory • D-branes in closed string field theory? Hashimoto and Hata HIKKO ♦A BRS invariant source term ♦tension of the brane cannot be fixed 2 Tensions of D-branes = Can one fix the normalization of the boundary states without using open strings? For noncritical strings, the answer is yes. Fukuma and Yahikozawa Let us describe their construction using SFT 3 for noncritical strings. c=0 noncritical strings + + double scaling limit String Field l Describing the matrix model in terms of this field, we obtain the string field theory for c=0 noncritical strings Kawai, N.I. 4 Stochastic quantization of the matrix model Jevicki and Rodrigues joining-splitting interactions 5 correlation functions Virasoro constraints FKN, DVV Virasoro constraints Schwinger-Dyson equations for the correlation functions ~ various vacua 6 Solitonic operators Fukuma and Yahikozawa Hanada, Hayakawa, Kawai, Kuroki, Matsuo, Tada and N.I. These coefficients are chosen so that From one solution to the Virasoro constraint, one can generate another by the solitonic operator. 7 These solitonic operators correspond to D-branes amplitudes with ZZ-branes state with D(-1)-brane = ghost D-brane 8 Okuda,Takayanagi critical strings? noncritical case is simple idempotency equation Kishimoto, Matsuo, Watanabe For boundary states, things may not be so complicated 9 If we have ・SFT with length variable ・nonlinear equation like the Virasoro constraint for critical strings, similar construction will be possible. -

String Field Theory, Nuclear Physics B271 (1986) 540

Nuclear Physics B271 (1986) 540-560 North-Holland, Amsterdam STRING FIELD THEORY* D. FRIEDAN Enrico Fermi Institute and Department of Physics, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA Received 13 May 1985 A gauge invariant field theory of the bosonic string is formulated following Siegel, Banks and Peskin, and Feigin and Fuks. The free field action is constructed from the Virasoro operators assuming only locality. The propagator is very regular at short distance, The natural jointing-split- ting interaction is described abstractly and a method of construction is sketched. A way is conjectured of reformulating the theory to be independent of the vacuum geometry. 1. Introduction String theory provides self-consistent quantizations of gravity, but there is no field theory of strings which is independent of the vacuum geometry [1]. This paper is an attempt in that direction. First a free field theory is constructed from the Virasoro operators and the assumptions of locality and gauge invariance. The joining-splitting interaction is described and a method of construction is sketched. The elements of the construction which depend on the vacuum geometry are isolated and there is some speculation on how to eliminate this dependence. The basic steps were taken by Siegel [2], who wrote the gauge-fixed Lorentz covariant field theory of the bosonic string in the BRST formalism. The string field ~(x ) is a scalar function of parametrized strings x~(s). It is represented as a state q, in the Hilbert space of a single parametrized string. The free field action, omitting the ghost fields, is S(q,) = ep*(H - 1)q~. -

Strings, Links Between Conformal Field Theory, Gauge Theory and Gravity Jan Troost

Strings, links between conformal field theory, gauge theory and gravity Jan Troost To cite this version: Jan Troost. Strings, links between conformal field theory, gauge theory and gravity. Mathematical Physics [math-ph]. Université Pierre et Marie Curie - Paris VI, 2009. tel-00410720 HAL Id: tel-00410720 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00410720 Submitted on 24 Aug 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Ecole´ Normale Sup´erieure Universit´ePierre et Marie Curie Paris 6 Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique Th`esed’Habilitation Universit´ePierre et Marie Curie Paris 6 Sp´ecialit´e: Physique Th´eorique Strings Links between conformal field theory, gauge theory and gravity pr´esent´eepar Jan TROOST pour obtenir l’habilitation `adiriger des recherches Soutenance le 20 mai 2009 devant le jury compos´ede : MM. Adel Bilal Rapporteurs : Bernard Julia Costas Kounnas Dieter L¨ust Matthias Gaberdiel Marios Petropoulos Marios Petropoulos Jean-Bernard Zuber Eliezer Rabinovici Contents 1 Before entering the labyrinth 7 2 Strings as links 15 2.1 Down to earth . 15 2.2 Lofty framework . 16 3 Continuous conformal field theory 23 3.1 One motivation . -

Ashoke Sen and S-Duality Winner of Fundamental Physics Prize

GENERAL ¨ ARTICLE Ashoke Sen and S-Duality Winner of Fundamental Physics Prize Dileep Jatkar The Fundamental Physics Prize Foundation de- clared names of nine scientists in a varietyof ar- easof theoreticalphysicsas recipients of the Fun- damentalPhysicsPrize.Thisarticle is a quick introduction to Ashoke Sen's scienti¯c achieve- ments. In addition, this article containssome discussion of his S-duality proposal and the Sen Dileep Jatkar is a conjecture, which fetched him the Fundamental Professor at Harish- Physics Prize. Chandra Research Institute, Allahabad. He works in theoretical physics and his area of interest is string theory. The poor man says,\O King, both of us are Loknath; while I am theone whose masters are thepeople, you are master of thepeople". 1. Citation of the FundamentalPhysics Prize The year 2012 marks the beginning of the Fundamen- talPhysicsPrizefounded by Russianentrepreneur Yuri Milner. In the inauguralyear the Foundation announced a list of nine recipients for their outstanding contribu- tion to various disciplines in theoreticalphysics.Asper their website, http://fundamentalphysicsprize.org, TheFundamental Physics Prize recognizes transforma- tive advances in the ¯eldof fundamental physics ... in- cluding advances in closelyrelated ¯elds with deep con- nections tophysics. Ashoke Sen, a professor attheHarish-Chandra Research Keywords Institute, Allahabad, India is one of the nine recipients Fundamental Physics Prize of this Prize. The citation for which he is awarded this 2012, S-duality, Sen conjecture. RESONANCE ¨ April 2013 323 GENERAL ¨ ARTICLE Ashoke Sen prize (asstated onthewebsite) is received the [Ashoke Sen is awarded the Fundamental Physics Prize] Fundamental for uncovering strikingevidenceof strong-weakduality Physics Prize for in certain supersymmetric string theories andgauge the- providinga ories,opening thepath to therealization that all string definitiveevidence theories are di®erent limits of the same underlying in favour of S- theory.