Sheffield and Rotherham Strategic Housing Market Assessment 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Laughton-En-Le-Morthen Parish

LAUGHTON-EN-LE-MORTHEN PARISH COUNCIL Venue: Virtual Meeting Date: Wednesday, 18th November, 2020 Time: 7.15 p.m. A G E N D A 1. Agenda (Pages 1 - 4) Page 1 Agenda Item 1 Laughton-en-le-Morthen Parish Council The Village Hall Firbeck Avenue Laughton-en-le-Morthen S25 1YD Clerk: Mrs C J Havenhand Telephone - 01709 528823 Email: [email protected] Notice of an ordinary meeting of Laughton-en-le-Morthen Parish Council to be held on WEDNESDAY 18th NOVEMBER 2020 at 7.15pm. The meeting will be held remotely via a remote meeting platform. Access - The remote meeting platform can be accessed by using the following link: Join Zoom Meeting https://us02web.zoom.us/j/89433462440?pwd=RWFoTUtZcTJ2cllJeWhXdk5PaVF6dz09 Meeting ID: 894 3346 2440 Password: 661423 By Landline - By ringing any of these UK numbers and keying in your meeting ID and Password when asked: • 0203 481 5240 • 0131 460 1196 • 0203 051 2874 • 0203 481 5237 Please note you that depending on your call plan you may be charged for these numbers. Find your local number: https://us02web.zoom.us/u/kdUrPoXGWf Meeting ID: 894 3346 2440 Password: 661423 This meeting is open to the public by virtue of the Public Bodies (Administration to Meetings) Act 1960 s1 and The Local Authorities (Coronavirus) (Flexibility of Local Authority Meetings) (England) Regulations 2020. Yours Faithfully Mrs Caroline Havenhand Clerk and Financial Officer 12TH November 2020 Apologies for absence should be notified to the Clerk prior to the meeting. Page 1 of 4 Laughton-en-le-Morthen Parish Council Agenda Ordinary Meeting 18th November 2020 Page 2 PUBLIC PARTICIPATION Following completion of the first business (election of Chairperson/receipt of declarations of Acceptance of office as necessary) and information on the recording of meetings, the Parish Council will invite members of the public to put questions on relevant parish matters or to make statements appertaining to items on the agenda for the meeting, prior to the commencement of other business. -

Hundreds of Homes for Sale See Pages 3, 4 and 5

Wandsworth Council’s housing newsletter Issue 71 July 2016 www.wandsworth.gov.uk/housingnews Homelife Queen’s birthday Community Housing cheat parties gardens fined £12k page 10 and 11 Page 13 page 20 Hundreds of homes for sale See pages 3, 4 and 5. Gillian secured a role at the new Debenhams in Wandsworth Town Centre Getting Wandsworth people Sarah was matched with a job on Ballymore’s Embassy Gardens into work development in Nine Elms. The council’s Work Match local recruitment team has now helped more than 500 unemployed local people get into work and training – and you could be next! The friendly team can help you shape up your CV, prepare for interview and will match you with a live job or training vacancy which meets your requirements. Work Match Work They can match you with jobs, apprenticeships, work experience placements and training courses leading to full time employment. securing jobs Sheneiqua now works for Wandsworth They recruit for dozens of local employers including shops, Council’s HR department. for local architects, professional services, administration, beauti- cians, engineering companies, construction companies, people supermarkets, security firms, logistics firms and many more besides. Work Match only help Wandsworth residents into work and it’s completely free to use their service. Get in touch today! w. wandsworthworkmatch.org e. [email protected] t. (020) 8871 5191 Marc Evans secured a role at 2 [email protected] Astins Dry Lining AD.1169 (6.16) Welcome to the summer edition of Homelife. Last month, residents across the borough were celebrating the Queen’s 90th (l-r) Cllr Govindia and CE Nick Apetroaie take a glimpse inside the apartments birthday with some marvellous street parties. -

The List of Pharmacies Registered to Sell Ppcs on Our Behalf Is Sorted Alphabetically in Postcode Order

The list of pharmacies registered to sell PPCs on our behalf is sorted alphabetically in postcode order. 0 NAME PREMISES ADDRESS 1 PREMISES ADDRESS 2 PREMISES ADDRESS 3 PREMISES ADDRESS 4 LLOYDS PHARMACY SAINSBURYS, EVERARD CLOSE ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 2QU BOOTS UK LIMITED 9 ST PETERS STREET ST.ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 3DH FREEMAN GRIEVES LTD 111-113 ST PETERS STREET ST.ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 3ET LLOYDS PHARMACY PARKBURY HOUSE ST PETER ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 3HD IMED PHARMACY 67 HATFIELD ROAD ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL1 4JE LLOYDS PHARMACY SAINSBURYS, BARNET ROAD LONDON COLNEY ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL2 1AB LLOYDS PHARMACY 17 RUSSELL AVENUE ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL3 5ES CROWN PHAMRACY 65 HIGH STREET REDBOURN ST ALBANS HERTFORDSHIRE AL3 7LW MANOR PHARMACY (WHEATHAMPSTEAD) LTD 2 HIGH STREET WHEATHAMPSTEAD HERTFORDSHIRE AL4 8AA BOOTS UK LIMITED 23-25 HIGH STREET HARPENDEN HERTFORDSHIRE AL5 2RU LLOYDS PHARMACY 40 HIGH STREET WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL6 9EQ LLOYDS PHARMACY 84 HALDENS WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 1DD BOOTS UK LIMITED 65 MOORS WALK WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 2BQ BOOTS UK LIMITED 31 COLE GREEN LANE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 3PP PEARTREE PHARMACY 110 PEARTREE LANE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 3UJ BOOTS UK LIMITED 126 PEARTREE LANE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL7 3XY BOOTS UK LIMITED 31 THE HOWARD CENTRE WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL8 6HA LLOYDS PHARMACY SAINSBURYS, CHURCH ROAD WELWYN GARDEN CITY HERTFORDSHIRE AL8 6SA LLOYDS PHARMACY 9 SHOPLANDS WELWYN GARDEN -

JLTC Playscript

JUST LIKE THE COUNTRY BY JOYCE HOLLIDAY FOR AGE EXCHANGE THEATRE THE ACTION TAKES PLACE, FIRST IN THE CENTRE, AND THEN IN THE OUTSKIRTS, OF LONDON, IN THE MID-NINETEEN TWENTIES. THE SET IS DESIGNED FOR TOURING AND SHOULD BE VERY SIMPLE. IT GIVES THREE DIFFERENT DOUBLE SETS. THE FIRST DOUBLE SET SHOWS, ON ONE SIDE, A SLUM BEDROOM, AND, ON THE OTHER, A PUB INTERIOR. THE SECOND SHOWS TWO VERY SIMILAR COUNCIL HOUSE INTERIORS. THE THIRD SHOWS TWO COUNCIL HOUSE EXTERIORS WITH VERY DIFFERENT GARDENS. THE STAGE FURNITURE IS KEPT TO THE MINIMUM AND CONSISTS OF A SMALL TABLE, ONE UPRIGHT CHAIR, AN ORANGE BOX AND TWO DECKCHAIRS. THE PLAY IS WRITTEN SPECIFICALLY FOR A SMALL TOURING COMPANY OF TWO MEN AND TWO WOMEN, EACH TAKING SEVERAL PARTS. VIOLET, who doubles as Betty FLO, who doubles as Phyllis, Mother, and Edna LEN, who doubles as the Housing Manager, the Builder, and Charlie GEORGE, who doubles as Alf, the Organ Grinder, the Doctor, Mr. Phillips, and Jimmy. THE FIRST DOUBLE SET SHOWS, ON ONE SIDE, A SLUM BEDROOM WITH TWO B TOGETHER. THROUGH THE BROKEN WINDOW, A VIEW OF BRICK WALLS AND ROO IS A REMOVABLE PICTURE HANGING ON A NAIL. THE OTHER SCREEN SHOWS A DINGY BUT PACKED WITH LIVELY PEOPLE. THE ACTORS ENTER FROM THE PUB SIDE, CARRYING GLASSES, ETC. THEY GRE AND THE AUDIENCE INDISCRIMINATELY, MOVING ABOUT A LOT, SPEAKING TIME, USING AND REPEATING THE SAME LINES AS EACH OTHER. GENERA EXCITEMENT. ALL CAST: Hello! Hello there! Hello, love! Watcha, mate! Fancy seeing you! How are you? How're you keeping? I'm alright. -

Historical and Contemporary Archaeologies of Social Housing: Changing Experiences of the Modern and New, 1870 to Present

Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Emma Dwyer School of Archaeology and Ancient History University of Leicester 2014 Thesis abstract: Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Emma Dwyer This thesis has used building recording techniques, documentary research and oral history testimonies to explore how concepts of the modern and new between the 1870s and 1930s shaped the urban built environment, through the study of a particular kind of infrastructure that was developed to meet the needs of expanding cities at this time – social (or municipal) housing – and how social housing was perceived and experienced as a new kind of built environment, by planners, architects, local government and residents. This thesis also addressed how the concepts and priorities of the Victorian and Edwardian periods, and the decisions made by those in authority regarding the form of social housing, continue to shape the urban built environment and impact on the lived experience of social housing today. In order to address this, two research questions were devised: How can changing attitudes and responses to the nature of modern life between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries be seen in the built environment, specifically in the form and use of social housing? Can contradictions between these earlier notions of the modern and new, and our own be seen in the responses of official authority and residents to the built environment? The research questions were applied to three case study areas, three housing estates constructed between 1910 and 1932 in Birmingham, London and Liverpool. -

Birmingham City Council Report to Cabinet 14Th May 2019

Birmingham City Council Report to Cabinet 14th May 2019 Subject: Houses in Multiple Occupation Article 4 Direction Report of: Director, Inclusive Growth Relevant Cabinet Councillor Ian Ward, Leader of the Council Members: Councillor Sharon Thompson, Cabinet Member for Homes and Neighbourhoods Councillor John Cotton, Cabinet Member for Social Inclusion, Community Safety and Equalities Relevant O &S Chair(s): Councillor Penny Holbrook, Housing & Neighbourhoods Report author: Uyen-Phan Han, Planning Policy Manager, Telephone No: 0121 303 2765 Email Address: [email protected] Are specific wards affected? ☒ Yes ☐ No If yes, name(s) of ward(s): All wards Is this a key decision? ☒ Yes ☐ No If relevant, add Forward Plan Reference: 006417/2019 Is the decision eligible for call-in? ☒ Yes ☐ No Does the report contain confidential or exempt information? ☐ Yes ☒ No 1 Executive Summary 1.1 Cabinet approval is sought to authorise the making of a city-wide direction under Article 4 of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order 2015. This will remove permitted development rights for the change of use of dwelling houses (C3 Use Class) to houses in multiple occupation (C4 Use Class) that can accommodate up to 6 people. 1.2 Cabinet approval is also sought to authorise the cancellation of the Selly Oak, Harborne and Edgbaston Article 4 Direction made under Article 4(1) of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order 1995. This is to avoid duplication as the city-wide Article 4 Direction will cover these areas. Page 1 of 8 2 Recommendations 2.1 That Cabinet authorises the Director, Inclusive Growth to prepare a non- immediate Article 4 direction which will be applied to the City Council’s administrative area to remove permitted development rights for the change of use of dwelling houses (C3 use) to small houses in multiple occupation (C4 use). -

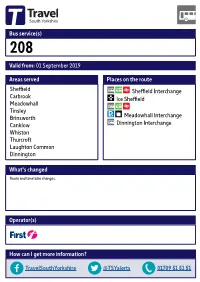

Valid From: 01 September 2019 Bus Service(S) What's Changed Areas

Bus service(s) 208 Valid from: 01 September 2019 Areas served Places on the route Sheffield Sheffield Interchange Carbrook Ice Sheffield Meadowhall Tinsley Brinsworth Meadowhall Interchange Canklow Dinnington Interchange Whiston Thurcroft Laughton Common Dinnington What’s changed Route and timetable changes. Operator(s) How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for service 208 01/02/2019 Scholes Parkgate Dalton Thrybergh Braithwell Ecclesfield Ravenfield Common Kimberworth East Dene Blackburn ! Holmes Meadowhall, Interchange Flanderwell Brinsworth, Hellaby Bonet Lane/ Bramley Wincobank Brinsworth Lane Maltby ! Longley ! Brinsworth, Meadowhall, Whiston, Worrygoose Lane/Reresby Drive ! Ñ Whitehill Lane/ Meadowhall Drive/ Hooton Levitt Bawtry Road Meadowhall Way 208 Norwood ! Thurcroft, Morthen Road/Green Lane Meadowhall, Whiston, ! Meadowhall Way/ Worrygoose Lane/ Atterclie, Vulcan Road Greystones Road Thurcroft, Katherine Road/Green Arbour Road ! Pitsmoor Atterclie Road/ Brinsworth, Staniforth Road Comprehensive School Bus Park ! Thurcroft, Katherine Road/Peter Street Laughton Common, ! ! Station Road/Hangsman Lane ! Atterclie, AtterclieDarnall Road/Shortridge Street ! ! ! Treeton Dinnington, ! ! ! Ulley ! Doe Quarry Lane/ ! ! ! Dinnington Comp School ! Sheeld, Interchange Laughton Common, Station Road/ ! 208! Rotherham Road 208 ! Aughton ! Handsworth ! 208 !! Manor !! Dinnington, Interchange Richmond ! ! ! Aston database right 2019 Swallownest and Heeley Todwick ! Woodhouse yright p o c Intake North Anston own r C Hurlfield ! data © y Frecheville e Beighton v Sur e South Anston c ! Wales dnan ! r O ! ! ! ! Kiveton Park ! ! ! ! ! ! Sothall ontains C 2019 ! = Terminus point = Public transport = Shopping area = Bus route & stops = Rail line & station = Tram route & stop 24 hour clock 24 hour clock Throughout South Yorkshire our timetables use the 24 hour clock to avoid confusion between am and pm times. -

Final General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Mary Mcleod Bethune Council House National Historic Site

Final General Management Plan Environmental Impact Statement Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site Washington, D.C. Final General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement _____________________________________________________________________________ Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site Washington, District of Columbia The National Park Service is preparing a general management plan to clearly define a direction for resource preservation and visitor use at the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site for the next 10 to 15 years. A general management plan takes a long-range view and provides a framework for proactive decision making about visitor use, managing the natural and cultural resources at the site, developing the site, and addressing future opportunities and problems. This is the first NPS comprehensive management plan prepared f or the national historic site. As required, this general management plan presents to the public a range of alternatives for managing the site, including a preferred alternative; the management plan also analyzes and presents the resource and socioeconomic impacts or consequences of implementing each of those alternatives the “Environmental Consequences” section of this document. All alternatives propose new interpretive exhibits. Alternative 1, a “no-action” alternative, presents what would happen under a continuation of current management trends and provides a basis for comparing the other alternatives. Al t e r n a t i v e 2 , the preferred alternative, expands interpretation of the house and the life of Bethune, and the archives. It recommends the purchase and rehabilitation of an adjacent row house to provide space for orientation, restrooms, and offices. Moving visitor orientation to an adjacent building would provide additional visitor services while slightly decreasing the impacts of visitors on the historic structure. -

NOTICE of POLL Election of Borough Councillors

NOTICE OF POLL Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council Election of Borough Councillors for Dinnington Ward Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of Borough Councillors for Dinnington Ward will be held on Thursday 6 May 2021, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of Borough Councillors to be elected is three. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposer (+) and Seconder (++) BARKLEY 46 New Road, Firbeck, The Green Party Wendy Hamilton (+) Anita Butcher (++) Ian David S81 8JY BOWERS 12 Nursery Crescent, Liberal Democrats Beverly A Thornley (+) Mark A Thornley (++) Phil North Anston, Sheffield, S25 4BQ CASTLEDINE-DACK (Address in Bolsover) Conservative Party Jonathan C V Hunt (+) Susan A Hunt (++) Sophie Candidate HAMILTON 46 New Road, Firbeck, The Green Party Ian D Barkley (+) David J Butcher (++) Wendy S81 8JY HART (Address in Rotherham) Independent Julie A Williams (+) Alexander A Williams Jean (++) MALLINDER (Address in Rotherham) Labour Party Judith O Dalton (+) Iain G L St. John (++) Jeanette SMITH 6 Victoria Street, Independent Emma Stanger (+) Mary P Smith (++) Dave Dinnington, Sheffield, S25 2SF VJESTICA 10 Caldbeck Place, Labour Party Judith O Dalton (+) Iain G L St. John (++) John North Anston, Sheffield, S25 4JY WATSON 6 Hillside, North Anston, Labour Party Judith O Dalton (+) Iain G L St. John (++) Gordon Sheffield, S25 4AZ WHOMERSLEY 11 Yew Tree Close, Conservative Party Jonathan C V Hunt (+) Susan A Hunt (++) Benjamin John Thurcroft, Rotherham, Candidate S66 9EY WOODING 6 Old School Walk, Conservative Party Jonathan C V Hunt (+) Susan A Hunt (++) Charlie Andrew Dinnington, Sheffield, Candidate S25 2AR 4. -

Rotherham Primary Care Estates Strategy V8

Rotherham Clinical Commissioning Group gy Amended November 2020 Intentionally Left Blank Rotherham Primary Care Estates Strategy 1 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6.4.2. Key Issues from Appraisal and Mapping 6.4.3. Central North Locality Estates Prioritisation 2. INTRODUCTION 6.5. Health Village / Central Locality 6.5.1. Property Assessment 3. STRATEGIC CONTEXT 6.5.2. Key Issues from Appraisal and Mapping 3.1. National Policy Context 6.5.3. Health Village / Central Locality Estate Prioritisation 3.2. Five Year Forward View 6.6. Maltby & Wickersley Locality 3.3. Delivering the Five Year Forward View 6.6.1. Premises Assessment 3.4. General Practice Forward View 6.6.2. Key Issues from Appraisal and Mapping 3.5. Next Steps on Five Year Forward View 6.6.3. Maltby & Wickersley Locality Estates Prioritisation 6.7. Wentworth South Locality 4. ROTHERHAM COMMISSIONING PRIORITIES, ORGANISATIONS AND 6.7.1. Premises Assessment STRATEGIC PARTNERS 6.7.2. Key Issues from Appraisal and Mapping 4.1. Health and Social Pen Picture of Rotherham 6.7.3. Wentworth South Locality Estates Prioritisation 4.1.1. Socio-economic Profile 6.8. Wath / Swinton Locality 4.1.2. Housing 6.8.1. Premises Assessment 4.1.3. Demographic Profile 6.8.2. Key Issues from Appraisal and Mapping 4.1.4. Health Needs 6.8.3. Wath / Swinton Locality Estates Prioritisation 4.2. Clinical Commissioning Groups 4.3. Local Authorities 7. FINANCIAL SUMMARY 4.4. Providers / Third Sector 4.5. South Yorkshire & Bassetlaw Integrated Care System (STP) 8. 2020 UPDATE 5. REVIEW OF THE PRIMARY CARE ESTATE ACROSS ROTHERHAM 5.1. -

School Bus Timetables and Travel Advice for Pupils Of: WALES HIGH SCHOOL 2013/14 ACADEMIC YEAR

School Bus Timetables and Travel Advice for pupils of: WALES HIGH SCHOOL 2013/14 ACADEMIC YEAR 1 Bus services to/from School School services are listed below and full timetables can be found on the following pages. Please note details are correct as at 9th July, should any changes take place prior to the start of term these will be communicated via the school. Service Number Route details Operator 632 Worksop – Lindrick – South Anston – School 633 South Anston - School Norwood – Killamarsh – Upperthorpe – High Moor – Woodall – Harthill 634 – School Carlton - Gateford – Shireoaks – Netherthorpe - Thorpe Salvin – Harthill – 635 School 636 Laughton village – Dinnington – North Anston – Todwick – School School – Harthill – Todwick – North Anston – Dinnington – Thurcroft 637 (LATE Bus) 638 Thurcroft – Brampton en le Morthen - School 639 Thurcroft – Laughton Common - School Other services which pass within 400 metres of the school are listed below and full timetables of these services are available from the Travel Information Centre in Rotherham, Sheffield or Dinnington Interchange or can be downloaded at www.travelsouthyorkshire.com/timetables. Service Number Route details Operator Rotherham - Waterthorpe - Killamarsh - Norwood - School - Todwick - 27 Dinnington 29 Rotherham – Swallownest – School – Harthill Sheffield - Swallownest – School – South Anston – North Anston - X5 Dinnington Operator Contact Details: BrightBus – 01909 550480 – www.brightbus.co.uk First – 01709 566000 – www.firstgroup.com/ukbus/south_yorkshire/ Should you need any further advice on anything in this pack then please call Traveline on 01709 515151. NB: SYPTE accept no responsibility for information provided on any other providers websites. 2 Service change details From September significant changes will be made to services to/from the school. -

Birmingham City Council City Council a G E N

BIRMINGHAM CITY COUNCIL CITY COUNCIL TUESDAY, 10 JULY 2018 AT 14:00 HOURS IN COUNCIL CHAMBER, COUNCIL HOUSE, VICTORIA SQUARE, BIRMINGHAM, B1 1BB A G E N D A 1 NOTICE OF RECORDING Lord Mayor to advise that this meeting will be webcast for live or subsequent broadcast via the Council's Internet site (www.civico.net/birmingham) and that members of the press/public may record and take photographs except where there are confidential or exempt items. 2 DECLARATIONS OF INTERESTS Members are reminded that they must declare all relevant pecuniary and non pecuniary interests arising from any business to be discussed at this meeting. If a disclosable pecuniary interest is declared a Member must not speak or take part in that agenda item. Any declarations will be recorded in the minutes of the meeting. 3 MINUTES 5 - 86 To confirm and authorise the signing of the Minutes of the meeting of the Council held on 12 June 2018. 4 LORD MAYOR'S ANNOUNCEMENTS (1400-1410) To receive the Lord Mayor's announcements and such communications as the Lord Mayor may wish to place before the Council. 5 PETITIONS (15 minutes allocated) (1410-1425) To receive and deal with petitions in accordance with Standing Order 9. As agreed by Council Business Management Committee a schedule of outstanding petitions is available electronically with the published papers for the meeting and can be viewed or downloaded. Page 1 of 118 6 QUESTION TIME (90 minutes allocated) (1425-1555) To deal with oral questions in accordance with Standing Order 10.3 A.