Contractual Rights and Duties of the Professional Athlete-Playing the Game in a Bidding War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estta1134132 05/17/2021 in the United States Patent And

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. https://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA1134132 Filing date: 05/17/2021 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Proceeding 91265831 Party Defendant Lana Sports, LLC Correspondence CRAIG E PINKUS Address BOSE MCKINNEY & EVANS LLP 111 MONUMENT CIRCLE STE #2700 INDIANAPOLIS, IN 46204 UNITED STATES Primary Email: [email protected] 317-684-5358 Submission Motion to Amend/Amended Answer or Counterclaim Filer's Name Craig E. Pinkus Filer's email [email protected], [email protected] Signature /Craig E. Pinkus/ Date 05/17/2021 Attachments Amended Answer and Counterclaim - Opposition No 91265831.pdf(647313 bytes ) Exhibit A TSDR records - Oppo No 91265831.pdf(5812950 bytes ) Exhibits B - F to Amended Answer and Counterclaim - Oppo No 91265831. pdf(4446947 bytes ) Exhibits G and H to Amended Answer and Counterclaim - Oppo No 9126583 1.pdf(1897697 bytes ) IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD NBA PROPERTIES, INC., v. Opposition No. 91265831 LANA SPORTS, LLC, Serial Nos. 88/702,750, 88/705,415, 88/703,294 AMENDED ANSWER In response to “NBA Properties, Inc.’s Motion to Dismiss Lana Sports, LLC’s Counterclaims and Strike Affirmative Defenses,” 13 TTABVUE pp. 1-19 filed April 26, 2021, and pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. Proc. Rule 15(a)(1)(B) and 37 CFR §2.107 and related provisions, Lana Sports, LLC (“Applicant”) amends its Answer, 6 TTABVUE pp. 1-14 filed February 12, 2021 to the Consolidated Notice of Opposition 1 TTABVUE pp. -

Division II Players in the Pros

NCAA DIVISION II PLAYERS WHO HAVE PLAYED PROFESSIONALLY IN U.S. (Through 2017-18 season) The following list consists of players who played NCAA Division II basketball who have or are currently playing in either the National Basketball Association or played in the American Basketball Association when that league existed. To make this list, a played has to have appeared in at least one regular season game in one of those professional leagues and played at the Division II school when the institution was affiliated in this division. PLAYER (SCHOOL) PROFESSIONAL TEAM(S) GAMES* POINTS* Darrell Armstrong (Fayetteville State) Orlando Magic 1994-03 503 5901 New Orleans Hornets 2003-04 93 982 Dallas Mavericks 2004-06 114 252 Indiana Pacers 2006-07 82 457 New Jersey Nets 2007-08 50 123 Career totals 840 7712 Carl Bailey (Tuskegee) Portland Trail Blazers 1981-82 1 2 Kenneth Bannister (St. Augustine’s) New York Knicks 1984-86 145 1110 Los Angeles Clippers 1988-91 108 391 Career totals 253 1501 Nathaniel Barnett, Jr. (Akron) Indiana Pacers (ABA) 1975-76 12 27 Billy Ray Bates (Kentucky State) Portland Trail Blazers 1979-82 168 2074 Washington Bullets/ Los Angeles Lakers 1982-93 19 123 Career totals 187 2197 Al Beard (Norfolk State) New Jersey Americans (ABA) 1967-68 12 30 Jerome Beasley (North Dakota) Miami Heat 2003-04 2 2 Spider Bennett (Winston-Salem State) Dallas Chaparrals/ Houston Mavericks (ABA) 1968-69 59 440 Delmer Beshore (California, Pa.) Milwaukee Bucks 1978-79 1 0 Chicago Bulls 1979-80 68 244 Career totals 69 244 Tom Black (South Dakota -

Examining the Evolution of Urban Multipurpose Facilities

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School July 2019 Examining the Evolution of Urban Multipurpose Facilities: Applying the Ideal-Type to the Facilities of the National Hockey League and National Basketball Association Benjamin Downs Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Other Kinesiology Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Downs, Benjamin, "Examining the Evolution of Urban Multipurpose Facilities: Applying the Ideal-Type to the Facilities of the National Hockey League and National Basketball Association" (2019). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4989. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4989 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. EXAMINING THE EVOLUTION OF URBAN MULTIPURPOSE FACILITIES: APPLYING THE IDEAL-TYPE TO THE FACILITIES OF THE NATIONAL HOCKEY LEAGUE AND NATIONAL BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Kinesiology by Benjamin Downs B.A., The College of Wooster, 2008 M.S., Mississippi State University, 2016 August 2019 This dissertation is dedicated to my daughter Stella Corinne. Thank you for being my source of inspiration and provider of levity throughout this process. I love you Birdie. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral advisor, Dr. -

Mychal Thompson

GOPHER BASKETBALL GOPHER HISTORY NCAA TOURNAMENT HISTORY 1972 MIDEAST REGION FIRST ROUND: Florida State 70, Minnesota 56 MIDEAST REGION CONSOLATION ROUND: Minnesota 77, Marquette 72 1982 MIDEAST REGION FIRST ROUND: Bye MIDEAST REGION SECOND ROUND: Minnesota 62, Tennessee-Chattanooga 61 MIDEAST REGION SEMIFINAL: Louisville 67, Minnesota 61 1989 EAST REGION FIRST ROUND: Minnesota 86, Kansas State 75 EAST REGION SECOND ROUND: Minnesota 80, Siena 67 EAST REGION SEMIFINALS: The Golden Gophers reached the “Elite Eight” of Duke 87, Minnesota 70 the 1990 NCAA tournament with victories against UTEP (64-61 OT), Northern Iowa (81-78) and 1990 Syracuse (82-75). Georgia Tech ended Minnesota’s chance of reaching the Final Four by defeating the SOUTHEAST REGION FIRST ROUND: Golden Gophers 93-91. With the help of four senior Minnesota 64, UTEP 61 (OT) starters, Minnesota finished the year with a 23-9 SOUTHEAST REGION SECOND ROUND: overall record. The four senior starters were Melvin Minnesota 81, Northern Iowa 78 Newbern (above, vs. Northern Iowa); Richard Coffey SOUTHEAST REGION SEMIFINALS: (left, vs. Syracuse); Willie Burton (lower left, vs. Georgia Tech), and Jim Shikenjanski (below, vs. Minnesota 82, Syracuse 75 UTEP). SOUTHEAST REGION FINAL: Georgia Tech 93, Minnesota 91 1999 WEST REGION FIRST ROUND: Gonzaga 75, Minnesota 63 2005 SYRACUSE REGION FIRST ROUND: #9 Iowa State 64, #8 Minnesota 53 TOTAL 7 Wins, 6 Losses (.538) Note: Minnesota appeared in the 1994, 1995 and 1997 NCAA Tournaments. Those games were later vacated due to student- athlete participation while ineligible because of a violation of NCAA rules. 152 MINNESOTA BASKETBALL 2007-08 GOPHER BASKETBALL GOPHER HISTORY NCAA TOURNAMENT RECORDS TEAM RECORDS GAME RECORDS Points: 91, vs. -

Enforceability of Professional Sports Contracts - What's the Harm in It

SMU Law Review Volume 35 Issue 3 Article 4 1981 Enforceability of Professional Sports Contracts - What's the Harm in It Bill Whitehill Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Bill Whitehill, Comment, Enforceability of Professional Sports Contracts - What's the Harm in It, 35 SW L.J. 803 (1981) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol35/iss3/4 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. ENFORCEABILITY OF PROFESSIONAL SPORTS CONTRACTS-WHAT'S THE HARM IN IT? by Bill Whitehill HE sports pages today' contain many stories of professional ath- letes and their contractual disputes.2 These disputes often arise when a new sports league is formed to compete with an already existing league. 3 Traditionally the new league offers significantly higher salaries4 to star athletes during their option year 5 to lure them to the new league and thus attract the attention and dollars of sports fans. Other con- 1. See, e.g., Bellinger Decides to Rejoin Tornado, Dallas Morning News, June 6, 1981, § B, at 5, col. I (professional soccer player who has signed contracts to play for teams in two different leagues works out arrangement to play for both during different seasons); Hill Sings Contract Blues, Earl Just Listens, Dallas Morning News, June 4, 1981, § B, at 1, col. 2 (two professional football players' contract disputes turn in different directions); Pearson Wants New Contract, Dallas Morning News, March 22, 1981, § B, at 1, col. -

BOB RASKIN: a COLORFUL and COMPLEX LIFE by Bob Howitt ([email protected])

BOB RASKIN: A COLORFUL AND COMPLEX LIFE By Bob Howitt ([email protected]) As youngsters, probably most of us have those mixed feelings about parental attendance at our sporting events. Do we want them there to see us make an error or miss the free throw or fail to make the tackle--not really, but if they are never at the game, how will they see our base hit, clutch jumper, or crucial play at the goal line. In maybe 300 games of high school baseball and basketball, Bob’s father Max was there so few times that Bob can remember the details clearly almost a half-century later. (He can also recall that, among other things, his father tried to scare Bob by saying he would be bald by 17 and that he would never do well at algebra.) “I struck out my first two times at the plate in one game, and my father left. Then I had two doubles. At a basketball game, I had two points at halftime, and Max left, which meant he missed a second half in which I scored 17 points.” The lost opportunities of his cold and distant father to create a close parental relationship in a way foretold a series of missed chances for the golden ring for Bob in his adult life. Nonetheless, as the bumper sticker says, and accurately for articulate, intelligent, energetic, personable people like Bob, when a window closes, somewhere a door opens. Bob was born in Brooklyn in 1941. At the time, Max ran a stand which sold sausage and root beer (6 cents for the combination) at 135th Street and Lenox Avenue in Harlem, a location which represented challenges to life, liberty, and the pursuit of profit. -

MINNESOTA BASKETBALL CONTACT INFORMATION 2016-17 MEDIA GUIDE Assoc

ATHLETIC COMMUNICATIONS MINNESOTA BASKETBALL CONTACT INFORMATION 2016-17 MEDIA GUIDE Assoc. Athletic Communications Director/ Men’s Basketball Contact: Dan Reisig 2016-17 TEAM INFORMATION RECORDS Office Phone: (612) 625-4389 2016-17 Roster 2 Career Records 54 Mobile Phone: (612) 419-6142 2016-17 Schedule 3 Season Records 57 Email: [email protected] Game Records 60 Fax: (612) 625-0359 PLAYER PROFILES Season Statistical Leaders 62 Web site: www.gophersports.com Gaston Diedhiou 4 1,000-Point Club 66 Ahmad Gilbert Jr. 6 Office Phone (612) 625-4090 Big Ten Career Records 69 Office Fax (612) 625-0359 Bakary Konaté 8 Big Ten Season Records 70 Website www.gophersports.com Nate Mason 10 Big Ten Game Records 72 Email [email protected] Dupree McBrayer 12 Season Big Ten Statistical Leaders 73 Jordan Murphy 14 Team Season Records 77 Mailing Address Davonte Fitzgerald 16 Team Game Records 78 Athletic Communications Darin Haugh 17 Opponent Records 80 University of Minnesota 275 Bierman Field Athletic Building Jarvis Johnson 18 Yearly Team Statistics 82 Reggie Lynch 19 516 15th Avenue SE Williams Arena Records 85 Minneapolis, Minn. 55455 Stephon Sharp 20 Williams Arena Attendance Figures 86 Akeem Springs 21 GOPHER RADIO NETWORK Amir Coffey 22 HISTORY General Manager Greg Gerlach Eric Curry 22 NCAA Tournament History 88 Play-by-Play Mike Grimm Michael Hurt 23 NIT History 90 Analyst Spencer Tollackson Brady Rudrud 23 NBA Draft History 91 All-Time NBA Roster 92 CREDITS COACHING STAFF Big Ten Awards 98 Editor: Dan Reisig Jeff Keiser Head Coach Richard Pitino -

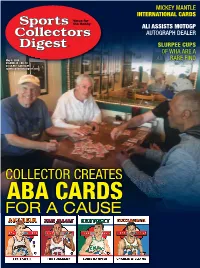

May 8, 2020 VOLUME 49 • NO. 10 US $4.99 • CAN $6.99

® May 8, 2020 VOLUME 49 • NO. 10 US $4.99 • CAN $6.99 sportscollectorsdigest.com Card Collecting by Joe Dynlacht Collector creates ABA card set Limited-edition set pays homage to players of the inaugural season and benefi ts players in fi nancial need hether you collect baseball, LIVING THE DREAM WHILE TRYING TO football, hockey or basketball HELP OTHERS Wcards, the thought of creating Many SCD readers who collect memora- your own card set has danced through your bilia, cards and autographs associated with the mind. Just admit it! But then, reality sets in ABA may recognize Scott’s name. He is the as you wonder how you would actually pull CEO of the Dropping Dimes Foundation, a off this feat. Maybe you fancy that you can do charity he co-founded in 2014 with Dr. John a better job at populating the backs of cards Abrams to raise money to provide assistance with text and stats than Company X, Y or Z. to members of the ABA family who are Maybe you have artistic tendencies and can experiencing fi nancial or medical hardships. design some gorgeous card fronts. Maybe you Abrams and Tarter recognized that many for- have access to the machinery and expertise to mer ABA players, as well as team and league print the card sheets, and cut, collate and box personnel and their families, were in need of them for delivery. And maybe you have the assistance to meet day-to-day needs because connections to players so you can include an they do not receive an NBA pension, nor were autographed card in your set. -

No Time for Excuses PBA League Opens 2Nd Season

ESPN TUESDAY NIGHT BOWLING LEAGUE S P E C I A L P O I N T S O F Kegler Chronicle INTEREST: VOLUME 1, ISSUE 9 FEBRUARY 10, 2014 “No time for excuses” Eliminated No Time for Excuses PBA League Begins. There champs Strikes for were some Reps fell 3-1, to a NBA of Bowl- interesting rejuvenated Franks ing Update results stem- and Burgers. ming from Duckpin the recently Dynasty and Danny revealed & the Miracles, who playoff struc- have been in the top ture. Was it 4 all year, have fell the pressure off playoff pace for of knowing the first time all year. that there were only 6 Black Ballers and weeks left in TFD make their first the regular appearance in the I N S I D E season? Not playoff race with THIS ISSUE: sure, but I strong performanc- know this much, if that infor- took it on the chin from the 2nd es. The difference between Week 11 mation caused this much turmoil, place Herrre’s Eliadio and Bump- 1st and last in the Roy Munson Recap I can’t wait to see the carnage ers Needed. division is a small 8 games so that makes the gap from 4th to 8th Week 12 that will ensue in the following Mine’s in the Gutter miniscule. Everyone in the RM Review weeks. Lets begin with the shocked Pick Up Artists 3-1, a leaders. Both Split Happens and team who sits atop the Power division is still alive. This should The Good, Diversity Personified surprisingly Rankings. -

33 Bob Portman (1966-69) #35 Paul Silas (1961-64) #45 Bob Gibson

RETIRED JERSEYS33 3 33 35 45 #33 #35 #45 Bob Portman Paul Silas Bob Gibson (1966-69) (1961-64) (1954-57) • Averaged a Creighton-record • Averaged 21.6 rebounds per • Led Creighton in scoring in 24.6 points per game for his game, third in NCAA history. both 1955-56 and 1956-57. career. • His 1,751 rebounds are sixth • Played for the Harlem • Averaged single-season in NCAA history and the most Globetrotters in 1957-58. school-record 29.5 points per ever by a three-year player. • Entered MVC Hall of Fame in game in 1967-68. • Scored 11,782 points and 2005 as an “Institutional Great” • Had single-game Creighton grabbed 12,357 rebounds in a • A member of the Major League record 51 points vs. Wisconsin- 16-year NBA career. Baseball Hall of Fame and All- Milwaukee on Dec. 16, 1967. • Also coached 10 seasons in Century Team. • Fourth-leading scorer in school the NBA. • Had 251 wins and won two Cy history (1,876). • Currently works for ESPN. Young Awards as a pitcher. BLUEJAY BASKETBALL33 3 105 44 4 ANNUAL LEADERS Scoring Year Player Pts. Avg. Rebounding Year Player Reb. Avg. Year Player Pts. Avg. ‘66-67 Bob Portman 457 18.3 Year Player Reb. Avg. ‘75-76 Rick Apke 202 7.7 ‘05-06 Johnny Mathies 405 13.5 ‘65-66 Tim Powers 559 21.5 ‘05-06 Anthony Tolliver 200 6.7 ‘74-75 Doug Brookins 193 7.1 ‘04-05 Nate Funk 586 17.8 ‘64-65 Elton McGriff 345 15.0 ‘04-05 Nate Funk 167 5.1 ‘73-74 Ted Wuebben 203 6.8 ‘03-04 Nate Funk 322 11.1 ‘63-64 Paul Silas 537 18.5 ‘03-04 Brody Deren 191 6.6 ‘72-73 Ted Wuebben 219 8.4 ‘02-03 Kyle Korver 604 17.8 ‘62-63 Paul Silas -

History Making

Volume 22 • No. 1 • spriNg 2013 MAKING HISTORY The Newsletter of the senator John Heinz History Center in Association with the smithsonian institution Totally Groovy! Visitors Flock to 1968 Exhibition The year 1968 represented a watershed in American history, a turning point for the nation and its people. From assassinations and conflicts, pop culture and free love, civil rights and women’s rights, the convergence of events in 1968 sent shockwaves across the country, including right here in Western Pa. Sports Artifact Spotlight: Time is running out for visitors to examine • Janis Joplin’s bellbottoms and The Pittsburgh Pipers this pivotal year as part of the Senator John feather boa, and other items Page 2 Heinz History Center’s new exhibition, from counterculture icons. 1968: The Year That Rocked America, • Interactive stations where presented by UPMC Health Plan. The visitors can cast their vote in the 8,000 square foot traveling exhibition from 1968 presidential election, test their 21st Annual History Makers the Minnesota History Center closes on knowledge of ’60s music, or design Award Dinner Preview May 12. their own psychedelic album cover. Page 3 • A special timeline which shows 1968: The Year That Rocked America how the transformative events takes visitors on a journey through the throughout the nation affected 1968: THE YEAR THAT Upcoming Exhibition: peak of the Vietnam War, assertions life here in Western Pa. ROCKED AMERICA The Civil War in Pennsylvania of Black Power at the Olympic Games, the national launch of “Mister Rogers’ Admission to the exhibition, which Page 4 PRESENTING SPONSOR Neighborhood,” stardom for musicians includes access to all six floors of the Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin, and the History Center, is $15 for adults, assassinations of Dr. -

OAAA) Cell: (505) 379-6071 [email protected] (505) 383-6214 Fax

New Mexico Office of African American Affairs Staff Directory Yvette Kaufman-Bell Executive Director Office: (505) 383-6221 Cell: (505) 690-4990 [email protected] Nicole Byrd Office staff members from (l-r), Tanya Montoya-Ramirez, Deputy Director Mbaember Joyce David-Wuam, Yvette Kaufman-Bell, Office: (505) 383-6219 Nicole Byrd, Beverly Jordan and Caleb Crump Cell: (505) 221-9171 [email protected] Beverly Jordan Executive Assistant Contact us: Office: (505) 383-6220 Cell: (505) 221-2863 New Mexico Office of [email protected] African American Affairs Tanya Montoya-Ramirez Budget Analyst Office: (505) 383-6218 310 San Pedro Dr. NE Suite 230 [email protected] Albuquerque, NM 87108 Mbaember Joyce David-Wuam Health Outreach Coordinator 1-866-747-6935 Toll-Free Office: (505) 383-6217 (505) 383-6222 (OAAA) Cell: (505) 379-6071 [email protected] (505) 383-6214 Fax Caleb Crump website: www.oaaa.state.nm.us Economics Outreach Coordinator Office: (505) 383-6216 Cell: (505) 205-0797 [email protected] www.oaaa.state.nm.us 2 Table of Contents Publication Staff Director’s Message•••4 Tavis Smiley in New Mexico•••5 Publish Layout & Design A Full House For Business Leadership Course•••6 Ron Wallace MLK Youth Commission: Foundation Building•••7 2015 New Mexico Black Expo•••8 - 13 Editor World Boxing Champion Bob Foster•••14 Delphine Dallas Basketball Hall of Famer Mel Daniels•••15 World Record Holder Adolph Plummer•••16 Contributors of Articles and NAACP State Conference•••17 Photos for this issue Sickle Cell Disease Education is Key•••18 Shammara H.