Gentriflcation and Displacement in Greater London: an Empirical and Theoretical Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HNL Appraisal Package 2 Pinn and Cannon Brook Initial Assessment Plus Document

FINAL HNL Appraisal Package 2 Pinn and Cannon Brook Initial Assessment Plus Document The Environment Agency March 2018 HNL Appraisal Package 2 Pinn and Cannon Brook IA plus document Quality information Prepared by Checked by Approved by Andy Mkandla Steve Edwards Fay Bull Engineer, Water Associate Director, Water Regional Director, Water Laura Irvine Graduate Engineer, Water Stacey Johnson Graduate Engineer, Water Revision History Revision Revision date Details Authorized Name Position Distribution List # Hard Copies PDF Required Association / Company Name Prepared for: The Environment Agency AECOM HNL Appraisal Package 2 Pinn and Cannon Brook IA plus document Prepared for: The Environment Agency Prepared by: Andy Mkandla Engineer E: [email protected] AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited Royal Court Basil Close Derbyshire Chesterfield S41 7SL UK T: +44 (1246) 209221 aecom.com © 2018 AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited. All Rights Reserved. This document has been prepared by AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited (“AECOM”) for sole use of our client (the “Client”) in accordance with generally accepted consultancy principles, the budget for fees and the terms of reference agreed between AECOM and the Client. Any information provided by third parties and referred to herein has not been checked or verified by AECOM, unless otherwise expressly stated in the document. No third party may rely upon this document without the prior and express written agreement of AECOM. Prepared for: The Environment Agency AECOM HNL -

Land at Yiewsley & West Drayton

TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 STOPPING UP OF HIGHWAY (LAND AT YIEWSLEY & WEST DRAYTON LEISURE CENTRE ROWLHEYS PLACE, WEST DRAYTON) ORDER 2020 Made 2020 The London Borough of Hillingdon makes this Order in exercise of its powers under section 247 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (“the Act “), and all other powers enabling it in that behalf: 1. The London Borough of Hillingdon authorises the stopping up of an area of the highway described in the Schedule to the Order and shown hatched blue on the attached Plan, in order to enable development to be carried out in accordance with the planning permission granted under Part III of the Act by the London Borough of Hillingdon on 27 April 2020 under application reference 75127/APP/2019/3221. 2. Where immediately before the date of this Order there is any apparatus of statutory undertakers under, in, on, over, along or across any highway authorised to be stopped up pursuant to this Order then, subject to section 261(4) of the Act those undertakers shall have the same rights as respects that apparatus after that highway is stopped up as they had immediately beforehand. 3. In this Order: “Plan” means the plan at appendix 1 marked 3478- ROWH-ICS-M2-C-Stopping Up signed by authority of the Deputy Chief Executive and Corporate Director of Resident Services and deposited at the London Borough of Hillingdon offices at Main Reception, Civic Centre, High Street, Uxbridge UB8 1UW. 4. This Order shall come into force on the date on which notice that it has been made is first published in accordance with section 252(10) of the Act, and may be cited as the “Stopping up of Highway (land at Yiewsley & West Drayton Leisure Centre Rowlheys Place, West Drayton) Order 2020”. -

The Membership of the Independent Labour Party, 1904–10

DEI AN HOP KIN THE MEMBERSHIP OF THE INDEPENDENT LABOUR PARTY, 1904-10: A SPATIAL AND OCCUPATIONAL ANALYSIS E. P. Thompson expressed succinctly the prevailing orthodoxy about the origins of the Independent Labour Party when he wrote, in his homage to Tom Maguire, that "the ILP grew from bottom up".1 From what little evidence has been available, it has been argued that the ILP was essentially a provincial party, which was created from the fusion of local political groups concentrated mainly on an axis lying across the North of England. An early report from the General Secretary of the party described Lancashire and Yorkshire as the strongholds of the movement, and subsequent historical accounts have supported this view.2 The evidence falls into three categories. In the first place labour historians have often relied on the sparse and often imperfect memoirs of early labour and socialist leaders. While the central figures of the movement have been reticent in their memoirs, very little literature of any kind has emerged from among the ordinary members of the party, and as a result this has often been a poor source. The official papers of the ILP have been generally more satisfactory. The in- evitable gaps in the annual reports of the party can be filled to some extent from party newspapers, both local and national. There is a formality, nevertheless, about official transactions which reduces their value. Minute books reveal little about the members. Finally, it is possible to cull some information from a miscellany of other sources; newspapers, electoral statistics, parliamentary debates and reports, and sometimes the memoirs of individuals whose connection 1 "Homage to Tom Maguire", in: Essays in Labour History, ed. -

TELOS CORPORATION 19986 Ashburn Road Ashburn, Virginia 20147-2358 SUPPLEMENT to INFORMATION STATEMENT for the SPECIAL MEETING of STOCKHOLDERS to BE HELD MAY 31, 2007

TELOS CORPORATION 19986 Ashburn Road Ashburn, Virginia 20147-2358 SUPPLEMENT TO INFORMATION STATEMENT FOR THE SPECIAL MEETING OF STOCKHOLDERS TO BE HELD MAY 31, 2007 On May 11, 2007, Telos Corporation (the “Company”) mailed an Information Statement (the “Information Statement”) to the holders of the Company’s 12% Cumulative Exchangeable Redeemable Preferred Stock (the “Public Preferred Stock”) as of March 8, 2007 (the “Record Date”). The Information Statement was delivered in connection with the Special Meeting of Stockholders to be held on May 31, 2007 for the purpose of electing two Class D directors to the Company’s Board of Directors. The Company is furnishing to the holders of the Public Preferred Stock on the Record Date this Supplement to Information Statement in order to provide additional information concerning Seth W. Hamot, one of the Class D director nominees. The Company believes that this additional information is material and should be considered when deciding whether to vote for Mr. Hamot. As previously reported, the Company is involved in litigation with Costa Brava Partnership III, L.P. (“Costa Brava”), a holder of the Company’s Public Preferred Stock (the “Litigation”). As disclosed in the Information Statement, Mr. Hamot is the President of Costa Brava’s general partner and also the Managing Member of Costa Brava’s investment manager. The Company discovered recently that Mr. Hamot and Costa Brava’s counsel have been communicating with Wells Fargo & Company. Wells Fargo Foothill, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Wells Fargo & Company, is the lender under the Company’s revolving credit facility (the “Credit Facility”). -

Council Agenda

Council Agenda City of Westminster Title: Council Meeting Meeting Date: Wednesday 2 May 2007 Time: 7.00pm Westminster Council House Venue: 97-113 Marylebone Road, London NW1 Members: All Councillors are hereby summoned to attend the Meeting for the transaction of the business set out below. Admission to the public gallery is by ticket, issued from the ground floor reception at Council House from 6.30pm. Please telephone if you are attending the meeting in a wheelchair or have difficulty walking up steps. There is wheelchair access by a side entrance. An Induction loop operates to enhance sound for anyone wearing a hearing aid or using a T transmitter. If you require any further information, please contact Nigel Tonkin. Tel: 020 7641 2756 Fax: 020 7641 8077 Minicom: 020 7641 5912 Email: [email protected] Corporate Website: www.westminster.gov.uk 2 1. Appointment of Relief Chairman To appoint a relief Chairman. 2. Minutes To sign the Minutes of the Meeting of the Council held on 21 March 2007. 3. Notice of Vacancy To note that Councillor Michael Vearncombe, Member for Marylebone High Street ward, resigned from the Council on Tuesday 27 March 2007. A by- election to fill the vacancy is being held on Thursday 3 May 2007. 4. Lord Mayor's Communications (a) The Lord Mayor to report that, at the invitation of Her Majesty, he attended and greeted the President of the Republic of Ghana and Mrs Kufour at their formal arrival in the UK at the start of their State Visit to this country. (b) The Lord Mayor to report that, alongside the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, he led the Walk of Witness march – starting from Whitehall Place, Westminster – to mark the 200 th anniversary of the abolition of the Slave Trade. -

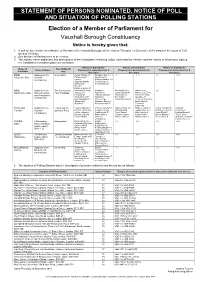

Statement of Persons Nominated, Notice of Poll and Situation of Polling Stations

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED, NOTICE OF POLL AND SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS Election of a Member of Parliament for Vauxhall Borough Constituency Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a Member of Parliament for Vauxhall Borough will be held on Thursday 12 December 2019, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. One Member of Parliament is to be elected. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Names of Signatories Names of Signatories Name of Description (if Home Address Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Candidate any) Assentors Assentors Assentors BOND (Address in the Green Party Keane Michael J(+) Sheppeck Neil A(++) (+) (++) (+) (++) Jacqueline Rose Vauxhall Picton-Howell King Robert A constituency) Indar H Wasserman Milo J G Argyropoulou Iris Prentis Roger A Wasserman Hemus Nicholas Nicola V Naylor Benjamin W BOOL (Address in the The Conservative Harmston-Gething Mawdsley Barr Stuart D(+) Gibson Best (+) (++) Sarah Anne-Marie Cities of London Party Candidate Joshua J(+) Paul M(++) Dyson Edward W Phoebe A L E(++) and Westminster Frost David Jefferson Michael Roberts Lee J Treherne Pollock constituency) Sunderland John Farrington Best Keith L Alexander B Harrison Edward J Rachael A E Tomlinson David S Trennery Thomas G Gibson Best Mawdsley Emma L Prain Alastair J Ophelia G Macgregor -

Back by Public Demand!

SEBRA NEWS W2 PROBABLY THE Back by MOST TALKED ABOUT Public Demand!GARDEN PARTY IN WESTMINSTER JOHN ZAMIT PRESENTS ISSUE No 93 A SEBRA PRODUCTION SUMMER 2018 “ “ ““ CARRYCARRY ONON NHSNHS ‘U’ THANK YOU NHS SEBRA SUMMER GARDEN PARTY 5 JULY 2018 ON THIS DAY 70 YEARS AGO THE NHS WAS BORN INTRODUCTION In this Issue From the THE GREATEST INTRODUCTION 10 BRIDGE GRAFITTI 40 LITTLE BARBER SHOP FROM THE CHAIRMAN 3 Chairman FROM THE EDITOR 4 Chairman: John Zamit SAFETY VALVE Email: [email protected] DELIVERY SCOOTER WOES 6 Phone: 020 7727 6104 BANK CLOSURE AT SHORT NOTICE 8 Mobile: 074 3825 8201 AN UNWANTED DEVELOPMENT? 9 Address: 2 Claremont Court LABOUR UPS ITS VOTE 11 Queensway, London W2 5HX AROUND BAYSWATER STATUE SPARKLING AGAIN 12 elcome to the Summer Also, we advised our local Councillors Also as you have may have read in the ON THE BUSES - HOLD ON TIGHT 13 2018 issue of SEBRA of our surprise at the publication of the press and on seen on TV, Business Rates "NOT FIT FOR PURPOSE" 17 NEWS W2. It's another report during a "purdah" period during can be crippling. (These rates are not set LUNCH IN THE SUN AT POMONA'S 21 bumper edition running to the local elections. As a result the report by Westminster Council and nor do they POLICING THE CAPITAL 24 Wover 120 pages. We delayed publishing was pulled by Stuart Love, Westminstrer receive the full amount levied). NEWCOMBE HOUSE BATTLE LINES 29 due to some late stories we wanted to City Council's Chief Executive. -

01708522666 Trusted Greenford 24HR Commercial Coffee Machine Engineers UB8 Denham UB9 Walk in Refrigertor Installation UB10 Ickenham UB18 Harmondsworth

01708522666 Trusted Greenford 24HR Commercial Coffee Machine Engineers UB8 Denham UB9 Walk In Refrigertor Installation UB10 Ickenham UB18 Harmondsworth We're THAMES WATER APPROVED plumber We are GAS SAFE (CORGI) REGISTERED plumbing, heating, gas engineers We have electrical NICEIC contractors available to you 24 HRS a day 7 days a week We are new RATIONAL SELF COOKING CATERING WHITE EFFICIENCY COMBI OVEN,COOKER APPROVED engineers We repair, maintain, service and install all commercial – domestic gas, commercial catering appliances, commercial – domestic air-conditioning, refrigeration, commercial laundry appliances services, commercial - domestic air-conditioning sytem, commercial - domestic refrigeration & freezer , commercial - domestic LPG , commercial – domestic heating, plumbing and multi trade services to all types of commercial and residential customers. All of our services are offered to types of customers. We offer various types of professional commercial services to all different types of trades customers and residential customers Commercial Air-Conditioning Repair, Air-Conditioning Installation & Ventilation Services - Air Conditioning installations -Air conditioning maintenance and repair - Domestic air-conditioning - Commercial Installations - Office Air Conditioning - Domestic Installations, Home Air Conditioning - Office commercial Air-Conditioning repair and installation - Portable Air Conditioners - R22 Gas Replacement on Air Conditioning - Air-con Gas Refill - Refrigeration Gas Refill - Air-conditioning engineer - Air-con -

No 379, July/August 2015

The Clapham Society Newsletter Issue 379 July/August 2015 Clapham Leaf Club The Club’s Grand Finale is on Saturday 4 July at Venn Street If you would like to go to the Summer Party on Market (10 am – 4 pm). Clapham Leaf Club is a project designed Thursday 9 July, and have not yet bought a ticket to enable pupils of the Clapham and Larkhall Collaborative there may still be one available. Check with Alyson primary schools (Allen Edwards, Clapham Manor, Heathbrook, Wilson on 020 7622 6360. Larkhall, Macaulay CE) to learn all aspects of growing their own food from preparing the soil using organic matter, to sowing seeds We have no regular meetings at Omnibus during July and and culturing their crops which will be harvested and sold as fruit August. The next meeting will be on Monday 21 September and vegetables or used in a cuisine and cooked and sold at the when Nobby Clark, photographer will talk about his work Market every year in July. as production photographer for many major theatre directors Now in its fifth year, the Grand Finale will show the great and for newspapers. Full details are on our website at efforts made by the schools over the past two terms. Each year claphamsociety.com/clapsocevents.html. Larkhall Primary deliver the best hanging baskets along with a Meanwhile we have the following walks during the summer: variety of fresh berries from their allotment and freshly laid eggs from their hen and duck pen! Heathbrook Primary will be showing Sunday 19 July their horticultural skills selling fresh lettuces, strawberries, spring Beware of the Flowers, ’Cos I’m Sure They’re Going to Get onions, peas and tomatoes and Allen Edwards Primary have been You – Yeah! A tour of Clapham Common looking at plants busy planting potatoes, carrots, onions, runner beans, tomatoes and as sources of medicines and poisons, and how we have used courgettes in March and radishes and rocket just before half term. -

The London Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment 2017

The London Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment 2017 Part of the London Plan evidence base COPYRIGHT Greater London Authority November 2017 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk More London London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 Copies of this report are available from www.london.gov.uk 2017 LONDON STRATEGIC HOUSING LAND AVAILABILITY ASSESSMENT Contents Chapter Page 0 Executive summary 1 to 7 1 Introduction 8 to 11 2 Large site assessment – methodology 12 to 52 3 Identifying large sites & the site assessment process 53 to 58 4 Results: large sites – phases one to five, 2017 to 2041 59 to 82 5 Results: large sites – phases two and three, 2019 to 2028 83 to 115 6 Small sites 116 to 145 7 Non self-contained accommodation 146 to 158 8 Crossrail 2 growth scenario 159 to 165 9 Conclusion 166 to 186 10 Appendix A – additional large site capacity information 187 to 197 11 Appendix B – additional housing stock and small sites 198 to 202 information 12 Appendix C - Mayoral development corporation capacity 203 to 205 assigned to boroughs 13 Planning approvals sites 206 to 231 14 Allocations sites 232 to 253 Executive summary 2017 LONDON STRATEGIC HOUSING LAND AVAILABILITY ASSESSMENT Executive summary 0.1 The SHLAA shows that London has capacity for 649,350 homes during the 10 year period covered by the London Plan housing targets (from 2019/20 to 2028/29). This equates to an average annualised capacity of 64,935 homes a year. -

Morgan Hayes, Including a Performance Diary and News of Recent Works, May Be Found At

Stainer & Bell CONTENTS Biographical Note .............................................................2 Music for Orchestra ..........................................................5 Music for String Orchestra ................................................6 Ensemble Works ...............................................................6 Works for Solo Instrument and Ensemble .......................10 Works for Flexible Instrumentation .................................11 Instrumental Chamber Music .........................................12 Works for Solo Piano .......................................................14 Choral Works ..................................................................16 Vocal Chamber Music .....................................................16 Works for Solo Voice .......................................................17 Discography....................................................................17 Alphabetical List of Works...............................................19 Ordering Information ......................................................20 Further information about the music of Morgan Hayes, including a performance diary and news of recent works, may be found at www.stainer.co.uk/hayes.html Cover design: Joe Lau August 2019 1 Morgan Hayes Born in 1973, Morgan Hayes reflects the cultural pluralism of his generation in his open and relaxed attitude to many kinds of musical expression. At the same time, he has pursued a single-minded artistic vision that has won him admirers from among the ranks -

CHINBROOK ACTION RESIDENTS TEAM Big Local Plan September 2017 2017-2019 (Plan Years 2 and 3)

CHINBROOK ACTION RESIDENTS TEAM Big Local Plan September 2017 2017-2019 (Plan Years 2 and 3) 1 | P a g e CHINBROOK ACTION RESIDENTS TEAM BIG LOCAL PLAN 1. Introduction 2. Chinbrook Context 3. Partnership 4. Vision and Priority Areas o Priority 1 : Health & Well-being o Priority 2 : Parks & Green Spaces o Priority 3 : Education, Training & Employment o Priority 4 : Community & Belonging o Priority 5 : Routes out of Poverty o Priority 6 : Community Investment 5. Consulting the Community 6. Plan for Years 2 & 3 7. Appendices 2 | P a g e Introduction from our Vice Chairs “Welcome to Chinbrook Big Local, we call ourselves Chinbrook Action Residents Team, or ChART for short. Together we are working to make Chinbrook an even better place for people to live, work and play. We are pleased to introduce our second plan. We worked hard as a steering group to take on board the comments and view of local residents to forge our next set of priorities. There was a strong sense of the need for everybody to work together to tackle the harsh economic climate that is facing many people up and down the country which is why we have added a new priority, Routes out of Poverty. Over the last year I feel ChART has really started to make an impact in the area, doing what we intended which is galvanising local community solidarity based on what local people say they need, helping them to come together to do so. We have moved from people saying “ChART? What’s that” to “ChART, What are you up to?” and it was great to get so much positive feedback about our projects from the consultation exercise we undertook during the summer.