Epistemological Intelligence Steven Bartlett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roots of Human Resistance to Animal Rights: Psychological and Conceptual Blocks

Roots of Human Resistance to Animal Rights: Psychological and Conceptual Blocks © Steven J. Bartlett 8 Animal L. 143 (2002) Publish Date: 2002 Place of Publication: http://www.animallaw.info/articles/arussbartlett2002.htm Roots of Human Resistance to Animal Rights: Psychological and Conceptual Blocks Animal law has focused attention on such interconnected issues as the property status of nonhuman animals, juristic personhood, and standing. These subjects are undeniably central concerns that dominate discussions of animal rights, but they do not relate to the most fundamental factors that are responsible both for human resistance to animal rights and for our species' well-entrenched, cruel, and self-righteous exploitation and destruction of nonhuman animals. In this comment, the author reviews recent advocacy of animal rights and offers the first study of human psychological and conceptual blocks that stand in the way of efforts on behalf of animal law and legislation. Paying long overdue attention to these obstacles provides a realistic framework for evaluating the effectiveness of attempts to initiate meaningful change. I am in favour of animal rights as well as human rights. That is the way of a whole human being. -- Abraham Lincoln I. INTRODUCTION: ANIMALS AS PROPERTY--IS THIS THE PROBLEM? Animals are property. These three words--and their legal implications and practical ramifications--define the most significant doctrines and cases . and the realities for current practitioners of animal law. [FN1] For many people in our society, the concept of legal rights for other animals is quite "unthinkable." That is because our relationship with the majority of animals is one in which we exploit them: we eat them, hunt them and use them in a variety of ways that are harmful to the animals. -

Evil Institutions: Steven Bartlett’S Analysis of Human Evil and Its Relevance for Anarchist Alternatives

Anarchist Studies 29.1 © 2021 issn 2633 8270 www.lwbooks.co.uk/journals/anarchiststudies/ Evil Institutions: Steven Bartlett’s Analysis of Human Evil and its Relevance for Anarchist Alternatives Brian Martin ABSTRACT The study of human evil, defined in a non-religious sense as serious damage to other people, animals and the environment, can be used to assess different social arrangements. Steven Bartlett’s analysis of the pathologies of human behaviour and thought provides a fruitful starting point for examining social institutions. Systems based on hierarchy and control, notably the military, bureaucracy and the state, provide the greatest facilitation of evil. Egalitarian systems are better placed to restrain the human capacity for causing harm. The study of evil offers a useful approach for understanding both the advantages of anarchism and the obstacles to moving towards it. Keywords: evil, social institutions, anarchism, bureaucracy, the state, the family INTRODUCTION It is easy to observe that humans, as individuals and as a species, do many things damaging to each other, to other species, and to the environment that supports them all. War, torture, terrorism, dictatorship, racism and systematic exploitation are just some of the toxic features of human societies. As well, humans enslave and exploit numerous other species, while humans themselves overpopulate and destroy the ecological systems that support life on earth. This is a roll call of destructive behaviours, individual and collective. One way to try to understand the proclivity of humans to hurt each other and destroy the environment is through the concept of human evil. Because of its reli- DOI:10.3898/AS.29.1.05 AAnarchistnarchist SStudiestudies 229.1.indd9.1.indd 8888 222/02/20212/02/2021 115:12:435:12:43 Evil Institutions 89 y gious connotations, this concept may not appeal to anarchists but, nevertheless, it potentially enables an understanding of a diverse set of social phenomena in a way that offers insights for anarchism. -

The Idea of a Metalogic of Reference

THE IDEA OF A METALOGIC OF REFERENCE by Steven James Bartlett Visiting Scholar in Philosophy and Psychology, Willamette University and Senior Research Professor, Oregon State University Website: http://www.willamette.edu/~sbartlet KEYWORDS: theory of reference, transcendental philosophy, metalogic of reference, self-reference, metalogical self-reference, reflexivity This paper was originally published in the Netherlands, in Methodology and Science: Interdisciplinary Journal for the Empirical Study of the Foundations of Science and Their Methodology, Vol. 9, No. 3, 1976, pp. 85-92. Methodology and Science ceased publication in the mid-1990s and all rights to this paper reverted to the author. This electronic version supplements the original text with internet-searchable keywords and, following the paper, references to some of the author’s subsequent publications that further develop this topic. The author has chosen to re-issue this work as a free open access publication under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs license, which allows anyone to distribute this work without changes to its content, provided that both the author and the original URL from which this work was obtained are mentioned, that the contents of this work are not used for commercial purposes or profit, and that this work will not be used without the author’s or his executor’s permission in derivative works (i.e., you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work without such permission). The full legal statement of this license may be found at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/legalcode © Steven James Bartlett, 2014 Historical Note his paper sought to state in a concise and comparatively informal, unsystematic, T and more accessible form the more technical approach the author developed during a research fellowship 1974-75 at the Max-Planck-Institut in Starnberg, Germany. -

THE SPECIES PROBLEM and ITS LOGIC: Inescapable Ambiguity and Framework-Relativity Steven James Bartlett

THE SPECIES PROBLEM AND ITS LOGIC: Inescapable Ambiguity and Framework-relativity Steven James Bartlett To cite this version: Steven James Bartlett. THE SPECIES PROBLEM AND ITS LOGIC: Inescapable Ambiguity and Framework-relativity. 2015. hal-01196519 HAL Id: hal-01196519 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01196519 Preprint submitted on 10 Sep 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Available from ArXiv, HAL, CogPrints, PhilSci-Archive THE SPECIES PROBLEM AND ITS LOGIC Inescapable Ambiguity and Framework-relativity Steven James Bartlett e-mail: sbartlet [at] willamette [dot] edu KEYWORDS: species problem, species concepts, definitions of species, similarity theory, logic of commonality, Theorem of the Ugly Duckling, Satosi Watanabe, Nelson Goodman, framework-relativity, Löwenheim-Skolem Theorem, Hilary Putnam, human speciation ABSTRACT For more than fifty years, taxonomists have proposed numerous alternative definitions of species while they searched for a unique, comprehensive, and persuasive definition. This monograph shows that these efforts have been unnecessary, and indeed have provably been a pursuit of a will o’ the wisp because they have failed to recognize the theoretical impossibility of what they seek to accomplish. -

Philosophical Positions That Self-Destruct

HOISTED BY THEIR OWN PETARDS: PHILOSOPHICAL POSITIONS THAT SELF-DESTRUCT by Steven James Bartlett Visiting Scholar in Philosophy and Psychology, Willamette University and Senior Research Professor, Oregon State University Website: http://www.willamette.edu/~sbartlet KEYWORDS: self-reference, pragmatical self-referential inconsistency, projective self- referential inconsistency, metalogical self-reference, conceptual pathology, therapeutic philosophy, philosophy of quantum theory This paper was originally published in the journal Argumentation, Vol. 2, 1988, pp. 221-232. The publisher of the journal wishes to have the following statement included here: “The final publication is available at http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF00178023.” The author’s version made available here includes a number of typographical corrections and is supplemented with internet-searchable keywords and an addendum of references to some of the author’s other publications that further develop this topic. This electronic version is made available as a free open access publication under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs license, which allows anyone to distribute this work without changes to its content, provided that the author, the original publishing journal, and the original URL from which this work was obtained are credited, that the contents of this work are not used for commercial purposes or profit, and that this work will not be used without the author’s or his executor’s permission in derivative works (i.e., you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work without such permission). The full legal statement of this license may be found at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/legalcode © Steven James Bartlett, 2014 [Originally published in Argumentation 2 (1988), pp. -

THE SPECIES PROBLEM and ITS LOGIC Inescapable Ambiguity and Framework-Relativity

Available from ArXiv, BioRxiv, CogPrints, PhilSci-Archive THE SPECIES PROBLEM AND ITS LOGIC Inescapable Ambiguity and Framework-relativity Steven James Bartlett e-mail: sbartlet [at] willamette [dot] edu KEYWORDS: species problem, species concepts, definitions of species, similarity theory, logic of commonality, Theorem of the Ugly Duckling, Satosi Watanabe, Nelson Goodman, framework-relativity, Löwenheim-Skolem Theorem, Hilary Putnam, human speciation ABSTRACT For more than fifty years, taxonomists have proposed numerous alternative definitions of species while they searched for a unique, comprehensive, and persuasive definition. This monograph shows that these efforts have been unnecessary, and indeed have provably been a pursuit of a will o’ the wisp because they have failed to recognize the theoretical impossibility of what they seek to accomplish. A clear and rigorous understanding of the logic underlying species definition leads both to a recognition of the inescapable ambiguity that affects the definition of species, and to a framework-relative approach to species definition that is logically compelling, i.e., cannot not be accepted without inconsistency. An appendix reflects upon the conclusions reached, applying them in an intellectually whimsical taxonomic thought experiment that conjectures the possibility of an emerging new human species. _________________________________ The author has chosen to issue this monograph as a free open access publication under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs license, which allows anyone to distribute this work without changes to its content, provided that both the author and the original URL from which this work was obtained are mentioned, that the contents of this work are not used for commercial purposes or profit, and that this work will not be used without the author’s or his executor’s permission in derivative works (i.e., you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work without such permission). -

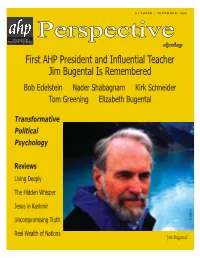

AHP Perspective OCTOBER 2008 Proof.Indd

O C T O B E R / N O V E M B E R 2 0 0 8 Association for PPerspectiveerspective Humanistic Psychology aahpweb.orghpweb.org First AHP President and Infl uential Teacher Jim Bugental Is Remembered Bob Edelstein Nader Shabagnam Kirk Schneider Tom Greening Elizabeth Bugental Transformative Political Psychology Reviews Living Deeply The Hidden Whisper Jesus in Kashmir Uncompromising Truth Tim Atkinson Real Wealth of Nations Jim Bugental OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2008 ahp PERSPECTIVE 1 ASSOCIATION for HUMANISTIC PSYCHOLOGY . since 1962, kindred spirits on the edge, where human potential and evolving consciousness meet AHP principles include integrity in personal and profes- sional interactions, authenticity, and trust in human relationships, compassion and deep listening skills, and respect for the uniqueness, value, independence, interdependence, and essential oneness of all beings. KEN EHRLICH AHP–ATP Joint Board Meeting, Calistoga, California, July 2006: back row: AHP President Cuf Ferguson, ATP Co-President Stu Sovatsky, Ray Siderius, Ray Greenleaf (ATP), Deb Oberg, Don Eulert, Colette Fleuridas (ATP), PAST PRESIDENTS AHP Past President Bruce Francis, Olga Bondarenko, Stan Charnofsky, Beth Tabakian (ATP); front row, Kathleen JAMES F. T. B UGENTAL AHP OFFICE & PERSONNEL Erickson, Bonnie Davenport, MA Bjarkman, Ken Ehrlich, Chip Baggett, ATP Co-President David Lukoff. SIDNEY M. JOURARD 510/769-6495; Fax: 510/769-6433, E. J. SHOBEN, JR. [email protected], 1516 Oak St., Suite #317, CHARLOTTE BÜHLER Alameda, CA 94501-2947, ahpweb.org Membership Director: Bonnie Davenport, S. STANSFELD SARGENT [email protected] AHP MEMBERSHIP JACK R. GIBB Web Producer: John Harnish, [email protected] connect with conscious community, GERARD V. -

Sappho's Journal

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Christ's Journal, by Paul Alexander Bartlett This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org ** This is a COPYRIGHTED Project Gutenberg eBook, Details Below ** ** Please follow the copyright guidelines in this file. ** Title: Christ's Journal Author: Paul Alexander Bartlett Editor: Steven James Bartlett Illustrator: Paul Alexander Bartlett Release Date: April 8, 2012 [EBook #39400] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CHRIST'S JOURNAL *** Produced by Al Haines FROM THE COVER OF CHRIST’S JOURNAL: In Christ’s Journal, the author takes a daring step in this unique novel and places the reader for the first time in the shoes of The Fisherman. In this finely crafted and historically realistic portrait of the ancient Biblical world, Bartlett recreates the moving story of the last months of Christ’s life as Jesus Himself may have experienced them when He brought to mankind a message of love and enduring hope. Bartlett’s writing has been praised by many leading authors, reviewers, and critics, among them: JAMES MICHENER, novelist: “I am much taken with Bartlett’s work and commend it highly.” CHARLES POORE in The New York Times: “...believable characters who are stirred by intensely personal concerns.” GRACE FLANDRAU, author and historian: “...Characters and scenes are so right and living...it is so beautifully done, one finds oneself feeling it is not fiction but actually experienced fact.” JAMES PURDY, novelist: “An important writer.. -

Encounters with Intellectual Suppression

ENCOUNTERS WITH INTELLECTUAL SUPPRESSION STEVEN JAMES BARTLETT s I stood in front of the elementary school class, my back to the A other students, my nose pressed in the center of a small circle drawn in chalk on the blackboard, my arms held out horizontally parallel to the floor, my palms facing down, the teacher began piling books on top of my extended hands. She warned me in a loud and harsh voice not to move!, and to keep my nose firmly pressed inside the circle she’d drawn on the black- board. She put a heavy book on one of my outstretched hands, and then another on my other hand, and warned me to balance the books and not, under any circumstances, to let them drop! Then she piled other books on until my arms shook and it was obvious that I could hold no more. Then, she was satisfied. She told me to stay in this position, and if my nose lost con- tact with the blackboard, or if I dropped my arms and any of the books, I would be punished more severely. I don’t remember how long I had to stand there—angry, humiliated and degraded—in front of the silent class, but it was long enough to leave an impression that has remained with me. I had asked an innocent and, I thought, interesting question. We were being taught Roman numerals. I had begun to wonder how it was possible for the Romans to add and subtract, multiply and divide, since apparently this would require a different technique from the one we were taught us- ing our system of writing numbers. -

Download Download

Sappho’s Journal — A Voice from the Past STEVEN JAMES BARTLETT Oregon State University and Willamette University Sappho’s Journal by Paul Alexander Bartlett. Foreword by Willis Barnstone. Autograph Editions, 2007. 172 pp., illustrated. $12.95 ISBN 978-0615156460 One of the most personally engaging ways to keep the classics alive is to enter into the world as it was experienced by a unique and fascinating indi- vidual from long ago. To be able to do this across the intervening rift of many centuries, when that person did not leave behind a detailed autobiography, can only be done, with vividness and authenticity, through the art of fiction. If we rely only on Sappho’s fragments of poetry that have escaped the gradual obliteration of time most of us can only vaguely glimpse the extraordinary woman who wrote some 2,600 years ago. In Sappho’s Journal, novelist and artist Paul Alexander Bartlett allows us to enter into the poet’s inner world, to experience her sense of beauty, her loves and fears, reflections, and dedica- tion. Based on a careful study of an- cient Greece and Sappho’s surviving fragments of poetry, Bartlett has re- created Sappho in a lyrical account of the life, passion, and faith of this re- Ancient Narrative, Volume 7, 97–103 98 STEVEN JAMES BARTLETT markable woman whose intimate journal takes us back to 642 B.C. Perhaps we could let Sappho speak here for herself in a sample passage from Sappho’s Journal: Villa Poseidon, Mytilene 642 B.C. Fog, as grey as a shepherd’s cloak, ruffled the bay for a day and a night. -

A Relativistic Theory of Phenomenological Constitution

A RELATIVISTIC THEORY OF PHENOMENOLOGICAL CONSTITUTION A Self-referential, Transcendental Approach to Conceptual Pathology STEVEN JAMES BARTLETT Copies of this Ph.D. dissertation —in print (hardbound or softbound), in PDF format, or microform— are available through ProQuest 789 E. Eisenhower Pkwy. Ann Arbor, MI 48108 734.997.4630 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.proquest.com/en-US/products/dissertations/orderingres.shtml Please refer to dissertation number 7905583 © Steven James Bartlett, 1970, 2013 This publication is made available by the author as an open access publication, freely downloadable to readers through any non-profit online depository under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs license, which allows anyone to distribute this work without changes to its content, provided that both the author and the original URL from which this work was obtained are mentioned, that the contents of this work are not used for commercial purposes or profit, and that this work will not be used without the copyright holder’s written permission in derivative works (i.e., you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work without such permission). The full legal statement of this license may be found at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/legalcode Volume I: French Volume II: English A RELATIVISTIC THEORY OF PHENOMENOLOGICAL CONSTITUTION: A SELF-REFERENTIAL, TRANSCENDENTAL APPROACH TO CONCEPTUAL PATHOLOGY A Dissertation submitted to the Faculte des Lettres et Sciences Humaines, Universite de Paris (X), Nanterre in a double-language format -- French (Vol. I) and English (Vol. II) -- in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Steven James Bartlett, B. -

The Worldview of Phenomenology

THE WORLDVIEW OF PHENOMENOLOGY . Steven James Bartlett An invited High Table Address given before the students and faculty of Raymond College, University of the Pacific, Stockton, California, December 10, 1969 INTRODUCTORY COMMENTS, NEARLY A HALF-CENTURY LATER Raymond College was an unusual experiment in American higher education, one that unfortunately was not to endure. I learned of the school thanks to the interest that Robert Maynard Hutchins took in my education. He was then the head of the Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions in Santa Barbara. Hutchins admired the poetry of my mother, American poet Elizabeth Bartlett; it was she who introduced me to Hutchins, toward the end of my sophomore year as a student in the Honors Division of the University of Santa Clara. Hutchins described to me the unique curriculum that was being offered by Raymond College, begun in 1962 and in its second year of operation. He urged me to give education at Raymond a try. Raymond College was a “cluster college” established by the University of the Pacific. The College offered a privileged, Oxford-style, close-community environment for learning, an extremely small faculty-to-student ratio, with many of the faculty living on campus in the student dormitories, an academic year consisting of three full-length semesters, and a bachelor’s degree obtainable in three years upon passing several days of comprehensive exams. The program of study consisted of some 27 courses, 22 of these required. Classes were very small, often consisting of half a dozen students or fewer; independent study courses, i.e., tutorials, were common and permitted a student to develop a certain level of specialization within a curriculum focused on the liberal arts.