The History of Sheep Breeds in Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 'Wild' Sheep of Britain

The 'Wild' Sheep of Britain </. C. Greig and A. B. Cooper Primitive breeds of sheep and goats, such as the Ronaldsay sheep of Orkney, could be in danger of disappearing with the present rapid decline in pastoral farming. The authors, both members of the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources in Edinburgh University, point out that, quite apart from their historical and cultural interest, these breeds have an important part to play in modern livestock breeding, which needs a constant infusion of new genes from unimproved breeds to get the benefits of hybrid vigour. Moreover these primitive breeds are able to use the poor land and live in the harsh environment which no modern hybrid sheep can stand. Recent work on primitive breeds of sheep and goats in Scotland has drawn attention not only to the necessity for conserving them, but also to the fact that there is no organisation taking a direct scientific in- terest in them. Primitive livestock strains are the jetsam of the Agricul- tural Revolution, and they tend to survive in Europe's peripheral regions. The sheep breeds are the best examples, such as the sheep of Ushant, off the Brittany coast, the Ronaldsay sheep of Orkney, the Shetland sheep, the Soay sheep of St Kilda, and the Manx Loaghtan breed. Presumably all have survived because of their isolation in these remote and usually infertile areas. A 'primitive breed' is a livestock breed which has remained relatively unchanged through the last 200 years of modern animal-breeding techniques. The word 'primitive' is perhaps unfortunate, since it implies qualities which are obsolete or undeveloped. -

Animal Nutrition

GCSE Agriculture and Land Use Animal Nutrition Food production and Processing For first teaching from September 2013 For first award in Summer 2015 Food production and Processing Key Terms Learning Outcomes Intensive farming Extensive farming • Explain the differences between intensive and Stocking rates extensive farming. Organic methods • Assess the advantages and disadvantages of intensive and extensive farming systems, Information including organic methods The terms intensive and extensive farming refer to the systems by which animals and crops are grown and Monogastric Digestive Tract prepared for sale. Intensive farming is often called ‘factory farming’. Intensive methods are used to maximise yields and production of beef, dairy produce, poultry and cereals. Animals are kept in specialised buildings and can remain indoors for their entire lifetime. This permits precise control of their diet, breeding , behaviour and disease management. Examples of such systems include ‘barley beef’ cattle units, ‘battery’ cage egg production, farrowing crates in sow breeding units, hydroponic tomato production in controlled atmosphere greenhouses. The animals and crops are often iStockphoto / Thinkstock.com fertilised, fed, watered, cleaned and disease controlled by Extensive beef cattle system based on pasture automatic and semi automatic systems such as liquid feed lines, programmed meal hoppers, milk bacterial count, ad lib water drinkers and irrigation/misting units. iStockphoto / Thinkstock.com Extensive farming systems are typically managed outdoors, for example with free-range egg production. Animals are free to graze outdoors and are able to move around at will. Extensive systems often occur in upland farms with much lower farm stocking rates per hectare. Sheep and beef farms will have the animals grazing outdoors on pasture and only brought indoors and fed meals during lambing season and calving season or during the part of winter when outdoor conditions are too harsh. -

Implications of Agri-Environment Schemes on Hefting in Northern England

Case Study 3 Implications of Agri-environment Schemes on Hefting in Northern England This case study demonstrates the implications of agri-environmental schemes in the Lake District National Park. This farm is subject of an ESA (Environmentally Sensitive Area) agreement. The farm lies at the South Eastern end of Buttermere lake in the Cumbrian Mountains. This is a very hard fell farm in the heart of rough fell country, with sheer rock face and scree slopes and much inaccessible land. The family has farmed this farm since 1932 when the present farmer’s grandfather took the farm, along with its hefted Herdwick flock, as a tenant. The farm was bought, complete with the sheep in 1963. The bloodlines of the present flock have been hefted here for as long as anyone can remember. A hard fell farm The farmstead lies at around 100m above sea level with fell land rising to over 800m. There are 20ha (50 acres) of in-bye land on the farm, and another 25ha (62 acres) a few miles away. The rest of the farm is harsh rough grazing including 365ha (900 acres) of intake and 1944ha (4,800acres) of open fell. The farm now runs two and a half thousand sheep including both Swaledales and Herdwicks. The farmer states that the Herdwicks are tougher than the Swaledales, producing three crops of lambs to the Swaledale’s two. At present there are 800 ewes out on the fell. Ewes are not tupped until their third year. Case Study 3 Due to the ESA stocking restriction ewe hoggs and gimmer shearlings are sent away to grass keep for their first two winters, from 1 st November to 1 st April. -

CATAIR Appendix

CBP and Trade Automated Interface Requirements Appendix: PGA April 24, 2020 Pub # 0875-0419 Contents Table of Changes ............................................................................................................................................4 PG01 – Agency Program Codes .................................................................................................................... 18 PG01 – Government Agency Processing Codes ............................................................................................. 22 PG01 – Electronic Image Submitted Codes.................................................................................................... 26 PG01 – Globally Unique Product Identification Code Qualifiers .................................................................... 26 PG01 – Correction Indicators* ...................................................................................................................... 26 PG02 – Product Code Qualifiers.................................................................................................................... 28 PG04 – Units of Measure .............................................................................................................................. 30 PG05 – Scie nt if ic Spec ies Code .................................................................................................................... 31 PG05 – FWS Wildlife Description Codes ..................................................................................................... -

English Nature Research Report

3.2 Grazing animals used in projects 3.2.1 Species of gradng animals Some sites utilised more than one species of grazing animals so the results in Table 5 are based on 182 records. The majority of sites used sheep and/or cattle and these species were used on an almost equal number of sites, Ponies were also widely used but horses and goats were used infrequently and pigs were used on just 2 sites. No other species of grazing livestock was recorded (a mention of rabbits was taken to refer to wild populations). Table 5. Species of livestock used for grazing Sheep Cattle Equines Goats Pigs Number of Sites 71 72 30 7 2 Percentage of Records 39 40 16 4 I 3.2.2 Breeds of Sheep The breeds and crosses of sheep used are shown in Table 6. A surprisingly large number of 46 breeds or crosses were used on the 71 sites; the majority can be considered as commercial, although hardy, native breeds or crosses including hill breeds such as Cheviot, Derbyshire Gritstone, Herdwick, Scottish Blackface, Swaledale and Welsh Mountain, grassland breeds such as Beulah Speckled Face, Clun Forest, Jacob and Lleyn and down breeds such as Dorset (it was not stated whether this was Dorset Down or Dorset Horn), Hampshire Down and Southdown. Continental breeds were represented by Benichon du Cher, Bleu du Maine and Texel. Rare breeds (i.e. those included on the Rare Breeds Survival Trust’s priority and minority lists) were well represented by Hebridean, Leicester Longwool, Manx Loghtan, Portland, Shetland, Soay, Southdown, Teeswater and Wiltshire Horn. -

Sheep Newz #14 Autumn 2019

Sheep NewZ #14 Autumn 2019 Hello Members, ASSOCIATION NEWS & VIEWS Thanks to all who have supported this issue of “Sheep NewZ”. It would be good to have some more photos/articles From The President each time other than those on the feature breed. I wonder how much money is being spent on bureaucracy in Hope everyone has had a great time over the the wool research, development and promotion sectors? holiday season. The weather was great here There seem to be several companies with great mission in the south over the summer and everyone statements but is anything much actually happening out seemed to be having lots of fun. there? NZ Merino seems to be achieving the most in both Lambs and ewes are bringing record prices this season advertising their product and developing new uses. which is very pleasing. However the same old fiddle plays Some of the Companies and their mission statements are: - the same old tune to try and bring prices down such as the Wool Research Organisation of New Zealand, “To uncertainty of the Brexit deal, Trump, and the Chinese promote, encourage and fund scientific or industry research economy which shows how we can be exposed so quickly. and information transfer that relates to the post harvest wool Hopefully common sense will prevail and our prices stay up industry” Several projects on going from 2013 – results?? at a reasonable level. Wool Industry Research Ltd – a subsidiary of the above “Focus on investment in research which increases the value It is really disappointing to see our farm training institutes and competiveness of commercial NZ wool based activity facing difficult times. -

"First Report on the State of the World's Animal Genetic Resources"

Country Report of Australia for the FAO First Report on the State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................5 CHAPTER 1 ASSESSING THE STATE OF AGRICULTURAL BIODIVERSITY THE FARM ANIMAL SECTOR IN AUSTRALIA.................................................................................7 1.1 OVERVIEW OF AUSTRALIAN AGRICULTURE, ANIMAL PRODUCTION SYSTEMS AND RELATED ANIMAL BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY. ......................................................................................................7 Australian Agriculture - general context .....................................................................................7 Australia's agricultural sector: production systems, diversity and outputs.................................8 Australian livestock production ...................................................................................................9 1.2 ASSESSING THE STATE OF CONSERVATION OF FARM ANIMAL BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY..............10 Major agricultural species in Australia.....................................................................................10 Conservation status of important agricultural species in Australia..........................................11 Characterisation and information systems ................................................................................12 1.3 ASSESSING THE STATE OF UTILISATION OF FARM ANIMAL GENETIC RESOURCES IN AUSTRALIA. ........................................................................................................................................................12 -

30297-Nidderdale 2012 Schedule 5:Layout 1

P R O G R A M M E (Time-table will be strictly adhered to where possible) ORDER OF JUDGING: Approx. 08.00 a.m. Breeding Hunters (commencing with Ridden Hunter Class) 09.00 a.m. Sheep Dog Trials 09.00 a.m. Carcass Class 09.00 a.m. Dogs Approx. 09.00 a.m. Riding and Turnout Approx. 09.00 a.m. Coloured Horse/Pony In-hand 09.15 a.m. Young Farmers’ Cattle 09.30 a.m. Dry Stone Walling Ballot 09.30 a.m. Beef Cattle (Local) 09.45 a.m. Sheep Approx. 10.00 a.m. All Other Cattle Judging commences Approx. 10.00 a.m. Children’s Riding Classes Approx. 10.00 a.m. Heavy Weight Agricultural Horses 10.00 a.m. Goats 10.00 a.m. Produce, Home Produce and Crafts (Benching 09.45 a.m.) 10.00 a.m. Flowers, Vegetables and Farm Crops (Benching 09.45 a.m.) 10.00 a.m. Poultry, Pigeons and Rabbits 10.30 a.m. ‘Pateley Pantry’ Stands Approx. 10.45 a.m. Mountain & Moorland 11.00 a.m. Pigs Approx. 11.00 a.m. Ridden Coloured 11.00 a.m. Trade Stands 1.15 p.m. Junior Shepherd/Shepherdess Classes (judged at the sheep pens) Approx. 2.00 p.m. Childrens’ Pet Classes (judged in the cattle rings) 2.00 p.m. Sheep - Supreme Championship MAIN RING ATTRACTIONS: 08.00-12.00 Judging - Horse and Pony classes 12.00-12.35 Inch Perfect Trials Display Team 12.35-12.55 Terrier Racing 12.55-1.30 ATV Manoeuvrability Test 1.30-2.00 Young Farmers Mascot Football 2.00-2.20 Parade of Fox Hounds by West of Yore Hunt & Claro Beagles 2.20-3.00 Inch Perfect Trials Display Team 3.00-3.30 GRAND PARADE AND PRESENTATION OF TROPHIES (Excluding Sheep, Goats, Pigs, Produce and WI) Parade of Tractors celebrating 8 decades of Nidderdale Young Farmers Club 3.30- Show Jumping OTHER ATTRACTIONS: Meltham & Meltham Mills Band playing throughout the day 12.00-12.15 St Cuthbert’s Primary School Band 12.15-1.15 Lofthouse & Middlesmoor Silver Band Forestry Exhibition Heritage Marquee Small Traders/Craft Marquee Pateley Pantry Marquee with Cookery Demonstrations 11.00 a.m. -

St.Kilda Soay Sheep & Mouse Projects

ST. KILDA SOAY SHEEP & MOUSE PROJECTS: ANNUAL REPORT 2009 J.G. Pilkington 1, S.D. Albon 2, A. Bento 4, D. Beraldi 1, T. Black 1, E. Brown 6, D. Childs 6, T.H. Clutton-Brock 3, T. Coulson 4, M.J. Crawley 4, T. Ezard 4, P. Feulner 6, A. Graham 10 , J. Gratten 6, A. Hayward 1, S. Johnston 6, P. Korsten 1, L. Kruuk 1, A.F. McRae 9, B. Morgan 7, M. Morrissey 1, S. Morrissey 1, F. Pelletier 4, J.M. Pemberton 1, 6 6 8 9 10 1 M.R. Robinson , J. Slate , I.R. Stevenson , P. M. Visscher , K. Watt , A. Wilson , K. Wilson 5. 1Institute of Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburgh. 2Macaulay Institute, Aberdeen. 3Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge. 4Department of Biological Sciences, Imperial College. 5Department of Biological Sciences, Lancaster University. 6 Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield. 7 Institute of Maths and Statistics, University of Kent at Canterbury. 8Sunadal Data Solutions, Edinburgh. 9Queensland Institute of Medical Research, Australia. 10 Institute of Immunity and Infection research, University of Edinburgh POPULATION OVERVIEW ..................................................................................................................................... 1 REPORTS ON COMPONENT STUDIES .................................................................................................................... 4 Vegetation ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 Weather during population -

Ewe Lamb in the Local Village Show Where Most of the Exhibits Were Taken from the Fields on the Day of the Show

Cotswold Sheep Society Newsletter Registered Charity No. 1013326 ` Autumn 2011 Hampton Rise, 1 High Street, Meysey Hampton, Gloucestershire, GL7 5JW [email protected] www.cotswoldsheepsociety.co.uk Council Officers Chairman – Mr. Richard Mumford Vice-Chairman – Mr. Thomas Jackson Secretary - Mrs. Lucinda Foster Treasurer- Mrs. Lynne Parkes Council Members Mrs. M. Pursch, Mrs. C. Cunningham, The Hon. Mrs. A. Reid, Mr. R Leach, Mr. D. Cross. Mr. S. Parkes, Ms. D. Stanhope Editors –John Flanders, The Hon. Mrs. Angela Reid Pat Quinn and Joe Henson discussing the finer points of……….? EDITORIAL It seems not very long ago when I penned the last editorial, but as they say time marches on and we are already into Autumn, certainly down here in Wales the trees have shed many of their leaves, in fact some began in early September. In this edition I am delighted that Joe Henson has agreed to update his 1998 article on the Bemborough Flock and in particular his work with the establishment to the RBST. It really is fascinating reading and although I have been a member of the Society since 1996 I have learnt a huge amount particularly as one of my rams comes from the RASE flock and Joe‟s article fills in a number of gaps in my knowledge. As you will see in the AGM Report, Pat Quinn has stepped down as President and Robert Boodle has taken over that position with Judy Wilkie becoming Vice President. On a personal basis, I would like to thank Pat Quinn for her willing help in supplying articles for the Newsletter and the appointment of Judy Wilkie is a fitting tribute to someone who has worked tirelessly over many years for the Society – thank you and well done to you both. -

Gwartheg Prydeinig Prin (Ba R) Cattle - Gwartheg

GWARTHEG PRYDEINIG PRIN (BA R) CATTLE - GWARTHEG Aberdeen Angus (Original Population) – Aberdeen Angus (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Belted Galloway – Belted Galloway British White – Gwyn Prydeinig Chillingham – Chillingham Dairy Shorthorn (Original Population) – Byrgorn Godro (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol). Galloway (including Black, Red and Dun) – Galloway (gan gynnwys Du, Coch a Llwyd) Gloucester – Gloucester Guernsey - Guernsey Hereford Traditional (Original Population) – Henffordd Traddodiadol (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Highland - Yr Ucheldir Irish Moiled – Moel Iwerddon Lincoln Red – Lincoln Red Lincoln Red (Original Population) – Lincoln Red (Poblogaeth Wreiddiol) Northern Dairy Shorthorn – Byrgorn Godro Gogledd Lloegr Red Poll – Red Poll Shetland - Shetland Vaynol –Vaynol White Galloway – Galloway Gwyn White Park – Gwartheg Parc Gwyn Whitebred Shorthorn – Byrgorn Gwyn Version 2, February 2020 SHEEP - DEFAID Balwen - Balwen Border Leicester – Border Leicester Boreray - Boreray Cambridge - Cambridge Castlemilk Moorit – Castlemilk Moorit Clun Forest - Fforest Clun Cotswold - Cotswold Derbyshire Gritstone – Derbyshire Gritstone Devon & Cornwall Longwool – Devon & Cornwall Longwool Devon Closewool - Devon Closewool Dorset Down - Dorset Down Dorset Horn - Dorset Horn Greyface Dartmoor - Greyface Dartmoor Hill Radnor – Bryniau Maesyfed Leicester Longwool - Leicester Longwool Lincoln Longwool - Lincoln Longwool Llanwenog - Llanwenog Lonk - Lonk Manx Loaghtan – Loaghtan Ynys Manaw Norfolk Horn - Norfolk Horn North Ronaldsay / Orkney - North Ronaldsay / Orkney Oxford Down - Oxford Down Portland - Portland Shropshire - Shropshire Soay - Soay Version 2, February 2020 Teeswater - Teeswater Wensleydale – Wensleydale White Face Dartmoor – White Face Dartmoor Whitefaced Woodland - Whitefaced Woodland Yn ogystal, mae’r bridiau defaid canlynol yn cael eu hystyried fel rhai wedi’u hynysu’n ddaearyddol. Nid ydynt wedi’u cynnwys yn y rhestr o fridiau prin ond byddwn yn eu hychwanegu os bydd nifer y mamogiaid magu’n cwympo o dan y trothwy. -

Hefted Flocks on the Lake District Commons and Fells

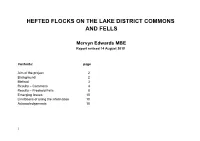

HEFTED FLOCKS ON THE LAKE DISTRICT COMMONS AND FELLS Mervyn Edwards MBE Report revised 14 August 2018 Contents: page Aim of the project 2 Background 2 Method 3 Results – Commons 4 Results – Freehold Fells 8 Emerging Issues 10 Limitations of using the information 10 Acknowledgements 10 1 HEFTED FLOCKS ON THE LAKE DISTRICT COMMONS AND FELLS Mervyn Edwards MBE Report revised 14 August 2018 Aim of the project The aim was to strengthen the knowledge of sheep grazing practices on the Lake District fells. The report is complementary to a series of maps which indicate the approximate location of all the hefted flocks grazing the fells during the summer of 2016. The information was obtained by interviewing a sample of graziers in order to illustrate the practice of hefting, not necessarily to produce a strictly accurate record. Background The basis for grazing sheep on unenclosed mountain and moorland in the British Isles is the practice of hefting. This uses the homing and herding instincts of mountain sheep making it possible for individual flocks of sheep owned by different farmers to graze ‘open’ fells with no physical barriers between these flocks. Shepherds have used this as custom and practice for centuries. Hefted sheep, or heafed sheep as known in the Lake District, have a tendency to stay together in the same group and on the same local area of land (the heft or heaf) throughout their lives. These traits are passed down from the ewe to her lambs when grazing the fells – in essence the ewes show their lambs where to graze.