The Weary Blues Droning a Drowsy Syncopated Tune, Rocking Back And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Solo Style of Jazz Clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 – 1938

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 The solo ts yle of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938 Patricia A. Martin Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Patricia A., "The os lo style of jazz clarinetist Johnny Dodds: 1923 - 1938" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1948. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1948 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SOLO STYLE OF JAZZ CLARINETIST JOHNNY DODDS: 1923 – 1938 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music By Patricia A.Martin B.M., Eastman School of Music, 1984 M.M., Michigan State University, 1990 May 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This is dedicated to my father and mother for their unfailing love and support. This would not have been possible without my father, a retired dentist and jazz enthusiast, who infected me with his love of the art form and led me to discover some of the great jazz clarinetists. In addition I would like to thank Dr. William Grimes, Dr. Wallace McKenzie, Dr. Willis Delony, Associate Professor Steve Cohen and Dr. -

AND ELECTIONS! Perby D"Ch* I Fraternity Sponsors Simi

m Derby Day Today-In The 'Oqmte^ Sororitiesn ^Vi'^c ~~ MAR 25 1960 *es, fo 'Strip' VOL. XXXV, No. urriccane Qn Field UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI CORAL GABLES, FLA. MAKCH 25,1960 A in "outhouses" on the St3t5 Sd- Id,, UM's 1122 sorori- ^^ vie this afternafternooo n for rLTm the Hth annual honors top AND ELECTIONS! perby D"Ch* i fraternity sponsors simi. iddv Spring Derby Day for I! &Ws sororities. ^ „,ritv will be stationed ^So^on the field in USG Week: in an ss wit*h~ th e "Day in the ^-throughout "Snatch Tinted members of Sigma Jazz, Races, rf'ote their top hats C «Tcamims. Girls are sup- ^i^atch them away, and STliS must then try to Lecture, Etc. recover them. By BARBARA McALPINE i .ls0 a variety of events are in 1 Activities ranging from student elections to bike Lr participants on the m- races, from Drew Pearson's lecture to Kai Winding's p.m. horn will highlight Undergraduate Student Govern I A four-legged race, strip ment Week, beginning Monday. {ease obstacle course and Strip The elections will be held Thursday and Friday for Tease are among the events positions on the USG Council and for school govern planned. ment offices. 4- from Miller Drive to Dickinson, I An egg and pepper contest, ALSO ON the ballot will be a to Walsh. The course whips on mystery event and baby-bottle referendum issue giving stu around to Ponce de Leon and sucking contests are also on the dents the opportunity to choose back up Miller Drive. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Download Booklet

559136 Hughes bk 17/06/2003 4:03 pm Page 1 de Hughes, le travail de l’auteur commença à attirer encore Hughes était fier de ces collaborations bien que ses davantage de musiciens dont les compositeurs noirs-américains préférences musicales continuèrent à se porter sur le blues et le Margaret Bonds et William Grant Still. On citera, pour mémoire, jazz et, dans les dernières années de sa vie, sur le gospel. Il inventa la mise en musique par Bonds de plusieurs poèmes de Hughes, d’ailleurs le théâtre musical gospel où une intrigue simple relie AMERICAN CLASSICS dont son fameux The Negro Speaks of River (Le Noir parle des entre-eux des gospels émouvants interprétés par d’éminents fleuves) de 1921. William Grant Still collabora avec lui à l’opéra chanteurs. Il connut tant le succès critique que commercial avec Troubled Island, d’après la pièce de Hughes sur la révolution qui des œuvres comme The Prodigal Son et, notamment, Black fut à l’origine de l’avènement de la république noire de Haïti. Nativity. Cette dernière fut peut-être volontairement conçue par L’opéra fut créé en 1949 à New York et reçut des critiques Hughes en réaction au classique de Noël de Gian Carlo Menotti, DREAMER mitigées. Ahmal and the Night Visitors. Les musiciens blancs furent également captivés par les Qu’il s’agisse de formes populaires ou plus exigeantes, tels œuvres de Hughes. La relation la plus étroite qu’entretint Hughes que le jazz ou le répertoire classique, Langston Hughes trouva A Portrait of Langston Hughes en tant que librettiste fut sans doute avec le compositeur immigré l’inspiration dans les œuvres des musiciens. -

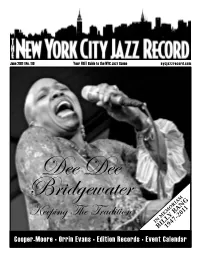

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

Old Wine New Bottles

Why must he waste his talent and the Wilber was never able to command a sit talent of his sidemen on an outmoded uation as could Bechet. He evidently conception that was hardly necessary in lacked Bechet’s utter self-confidence His the first place? (D.DeM.) vibrato, while similar to his mentor’s, uiiiimiimiimiimitiimiimmitiiiiiiiiimiiitiiiiiiiiiiiuiiimiiiiimiiitiiiimutimiiiM sounded nervous; Bechet’s was an indis pensable adjunct to his playing and en hanced his expressiveness rather than de OLD WINE tracted from it, as Wilber’s did. The HRS Bechet-Spanier sides are not NEW BOTTLES only Bechet gems, but are some of the best mimiiiiiiHiiuuiiimimimmmimiiiiumiitiiitiHiiiiiiitmitiiiitiiiimiiuHmiiiuiiiiM jazz records ever made, though collectors have tended to ignore them. There was no Sidney Bechet effort to re-create days beyond recall Four « IN MEMOR1AM—Riverside RLP 138/139; Sweet Lorraine; Up the Lazy River; China Boy; excellent jazzmen got together and just Four or Five Times; That's Aplenty; If / Could played. Of course, some of the intros and Be with You; Squeeze Me; Sweet Sue; I Got Rhythm; September Song; Whot; Love Me with endings were no doubt rehearsed, but the Feeling; Baby, Won't You Please Come Hornet; lasting value of these records lies in the Blues Improvisation; I’m Through, Goodbye; Waste No Tears; Dardanella; I Never knew; breathless Bechet solos and the driving Broken Windmill; Without a Home. ensembles. And if any of the kiddies com Personnel: Tracks 1-8: Bechet, clarinet, soprano ing along these days think that drums are saxophone; Muggsy Spanier, cornet; Carmen Mas tern. guitar; Wellman Braud, bass. -

Savoy and Regent Label Discography

Discography of the Savoy/Regent and Associated Labels Savoy was formed in Newark New Jersey in 1942 by Herman Lubinsky and Fred Mendelsohn. Lubinsky acquired Mendelsohn’s interest in June 1949. Mendelsohn continued as producer for years afterward. Savoy recorded jazz, R&B, blues, gospel and classical. The head of sales was Hy Siegel. Production was by Ralph Bass, Ozzie Cadena, Leroy Kirkland, Lee Magid, Fred Mendelsohn, Teddy Reig and Gus Statiras. The subsidiary Regent was extablished in 1948. Regent recorded the same types of music that Savoy did but later in its operation it became Savoy’s budget label. The Gospel label was formed in Newark NJ in 1958 and recorded and released gospel music. The Sharp label was formed in Newark NJ in 1959 and released R&B and gospel music. The Dee Gee label was started in Detroit Michigan in 1951 by Dizzy Gillespie and Divid Usher. Dee Gee recorded jazz, R&B, and popular music. The label was acquired by Savoy records in the late 1950’s and moved to Newark NJ. The Signal label was formed in 1956 by Jules Colomby, Harold Goldberg and Don Schlitten in New York City. The label recorded jazz and was acquired by Savoy in the late 1950’s. There were no releases on Signal after being bought by Savoy. The Savoy and associated label discography was compiled using our record collections, Schwann Catalogs from 1949 to 1982, a Phono-Log from 1963. Some album numbers and all unissued album information is from “The Savoy Label Discography” by Michel Ruppli. -

The Recordings

Appendix: The Recordings These are the URLs of the original locations where I found the recordings used in this book. Those without a URL came from a cassette tape, LP or CD in my personal collection, or from now-defunct YouTube or Grooveshark web pages. I had many of the other recordings in my collection already, but searched for online sources to allow the reader to hear what I heard when writing the book. Naturally, these posted “videos” will disappear over time, although most of them then re- appear six months or a year later with a new URL. If you can’t find an alternate location, send me an e-mail and let me know. In the meantime, I have provided low-level mp3 files of the tracks that are not available or that I have modified in pitch or speed in private listening vaults where they can be heard. This way, the entire book can be verified by listening to the same re- cordings and works that I heard. For locations of these private sound vaults, please e-mail me and I will send you the links. They are not to be shared or downloaded, and the selections therein are only identified by their numbers from the complete list given below. Chapter I: 0001. Maple Leaf Rag (Joplin)/Scott Joplin, piano roll (1916) listen at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9E5iehuiYdQ 0002. Charleston Rag (a.k.a. Echoes of Africa)(Blake)/Eubie Blake, piano (1969) listen at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R7oQfRGUOnU 0003. Stars and Stripes Forever (John Philip Sousa, arr. -

The Weary Blues” and “Jazztet Muted” by Langston Hughes

Department of English Putting Jazz on the Page: “The Weary Blues” and “Jazztet Muted” by Langston Hughes Ralph Hertzberg McKnight Bachelor’s degree Project Literature Fall, 2018 Supervisor: Magnus Ullén Abstract The goal of this essay is to look at the poems “The Weary Blues” and “JAZZTET MUTED” (hereafter to be referred to as “JAZZTET”) by Langston Hughes and examine their relationships to both the blues and jazz structurally, lyrically, and thematically. I examine the relationship of blues and jazz to the African-American community of Harlem, New York in the 1920’s and the 1950’s when the poems were respectively published. Integral to any understanding of what Hughes sought to accomplish by associating his poetry so closely with these music styles are the contexts, socially and politically, in which they are produced, particularly with respect to the African-American experience. I will examine Hughes’ understanding of not only the sound of the two styles of music but of what the music represents in the context of African-American history and how he combines these to effectively communicate blues and jazz to the page. Keywords: Langston Hughes; “The Weary Blues”; “JAZZTET MUTED”; the blues; jazz; Harlem; be-bop; the “Jazz-Age”; African-American history; “jazz poetry” Hertzberg McKnight 1 The poetry of Langston Hughes is inextricably linked to the new music he heard pouring out of the apartment windows and nightclub doorways of 1920s, and later, 1940s Harlem. Hughes was quick to identify the significance of this truly original art form and used it as a means to express the emotions and lived realities of the mostly African-American residents he saw on Harlem streets. -

The Influence of Louis Armstrong on the Harlem Renaissance 1923-1930

ABSTRACT HUMANITIES DECUIR, MICHAEL B.A. SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY AT NEW ORLEANS, 1987 M.A. THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, 1989 THE INFLUENCE OF LOUIS ARMSTRONG ON THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE 1923–1930 Committee Chair: Timothy Askew, Ph.D. Dissertation dated August 2018 This research explores Louis Armstrong’s artistic choices and their impact directly and indirectly on the African-American literary, visual and performing arts between 1923 and 1930 during the period known as the Harlem Renaissance. This research uses analyses of musical transcriptions and examples of the period’s literary and visual arts to verify the significance of Armstrong’s influence(s). This research also analyzes the early nineteenth century West-African musical practices evident in Congo Square that were present in the traditional jazz and cultural behaviors that Armstrong heard and experienced growing up in New Orleans. Additionally, through a discourse analysis approach, this research examines the impact of Armstrong’s art on the philosophical debate regarding the purpose of the period’s art. Specifically, W.E.B. Du i Bois’s desire for the period’s art to be used as propaganda and Alain Locke’s admonitions that period African-American artists not produce works with the plight of blacks in America as the sole theme. ii THE INFLUENCE OF LOUIS ARMSTRONG ON THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE 1923–1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY MICHAEL DECUIR DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA AUGUST 2018 © 2018 MICHAEL DECUIR All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My greatest debt of gratitude goes to my first music teacher, my mother Laura. -

![Palm Garden. DH Says B^/Was Fourteen Then, That the Year Was 192 0 F ^0^ [?]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5519/palm-garden-dh-says-b-was-fourteen-then-that-the-year-was-192-0-f-0-1165519.webp)

Palm Garden. DH Says B^/Was Fourteen Then, That the Year Was 192 0 F ^0^ [?]

OARNELL HOWARD 1 I [of 3]-Digest-Re typed April 21, 1957 Also present: Nesuhi Ertegun, Robert Campbell Darnell Howard was born July 25, 1906, in Chicago [Illinois]. NE says Muggsy [Spanier] told him he [also] was born that year, but DH says Muggsy is older. DH was born at 3528 Federal Street (two bloclcs from Armour Institute, which is now Illinois Institute of Technology). DH began studying his first instrument, violin,, at age seven; he studied with the same teacher who gave his father some lessons; his fatlaer played ciolin, comet and piano, and worked in night clubs around Chicago; he was working at [Pony?] Moore's at 21st and Wabash/ when he became il-1. DH says Bob Scobey or Turk [Murphy] told him that NE was a first-rate photographer. DH's father played all kinds of music, as DH has. EH studied violin until he was fourteen years old, when he ran away from home. His violin teacher was anj:,old man named Jol-inson. DH joined the union when he was twelve; h^s was sponsored by Clarence Jones; DH wente to worX [with Jones?] at the Panorama Theater; instumnentation was violin, pianc^ comet and drums. The school board made DH i^uit because of his age. The band played for motion pictures; they read their music. DH made 1-iis musical debut when he was nine years old, playing in a chsrch/ with his mother playing fhe piano. DH was induced to run away from 'home because be couldn't work in Chicago; to went with John Wycliffe's [c£. -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron.