Gully-And-Headcut-Repair.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Biology and Management of the River Dee

THEBIOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OFTHE RIVERDEE INSTITUTEofTERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY NATURALENVIRONMENT RESEARCH COUNCIL á Natural Environment Research Council INSTITUTE OF TERRESTRIAL ECOLOGY The biology and management of the River Dee Edited by DAVID JENKINS Banchory Research Station Hill of Brathens, Glassel BANCHORY Kincardineshire 2 Printed in Great Britain by The Lavenham Press Ltd, Lavenham, Suffolk NERC Copyright 1985 Published in 1985 by Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Administrative Headquarters Monks Wood Experimental Station Abbots Ripton HUNTINGDON PE17 2LS BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATIONDATA The biology and management of the River Dee.—(ITE symposium, ISSN 0263-8614; no. 14) 1. Stream ecology—Scotland—Dee River 2. Dee, River (Grampian) I. Jenkins, D. (David), 1926– II. Institute of Terrestrial Ecology Ill. Series 574.526323'094124 OH141 ISBN 0 904282 88 0 COVER ILLUSTRATION River Dee west from Invercauld, with the high corries and plateau of 1196 m (3924 ft) Beinn a'Bhuird in the background marking the watershed boundary (Photograph N Picozzi) The centre pages illustrate part of Grampian Region showing the water shed of the River Dee. Acknowledgements All the papers were typed by Mrs L M Burnett and Mrs E J P Allen, ITE Banchory. Considerable help during the symposium was received from Dr N G Bayfield, Mr J W H Conroy and Mr A D Littlejohn. Mrs L M Burnett and Mrs J Jenkins helped with the organization of the symposium. Mrs J King checked all the references and Mrs P A Ward helped with the final editing and proof reading. The photographs were selected by Mr N Picozzi. The symposium was planned by a steering committee composed of Dr D Jenkins (ITE), Dr P S Maitland (ITE), Mr W M Shearer (DAES) and Mr J A Forster (NCC). -

Cumulative Effective Stream Power and Bank Erosion on the Sacramento River, California, Usa1

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN WATER RESOURCES ASSOCIATION AUGUST AMERICAN WATER RESOURCES ASSOCIATION 2006 CUMULATIVE EFFECTIVE STREAM POWER AND BANK EROSION ON THE SACRAMENTO RIVER, CALIFORNIA, USA1 Eric W. Larsen, Alexander K. Fremier, and Steven E. Greco2 ABSTRACT: Bank erosion along a river channel determines the INTRODUCTION pattern of channel migration. Lateral channel migration in large alluvial rivers creates new floodplain land that is essential for Natural rivers and their surrounding areas consti- riparian vegetation to get established. Migration also erodes tute some of the world’s most diverse, dynamic, and existing riparian, agricultural, and urban lands, sometimes complex terrestrial ecosystems (Naiman et al., 1993). damaging human infrastructure (e.g., scouring bridge founda- Land deposition on the inside bank of a curved river tions and endangering pumping facilities) in the process. channel is a process that creates opportunities for Understanding what controls the rate of bank erosion and asso- vegetation to colonize the riparian corridor (Hupp and ciated point bar deposition is necessary to manage large allu- Osterkamp, 1996; Mahoney and Rood, 1998). Point vial rivers effectively. In this study, bank erosion was bar deposition and outside bank erosion are tightly proportionally related to the magnitude of stream power. Linear coupled. These physical processes (which constitute regressions were used to correlate the cumulative stream channel migration) maintain ecosystem heterogeneity power, above a lower flow threshold, with rates of bank erosion in floodplains over space and time (Malanson, 1993). at 13 sites on the middle Sacramento River in California. Two Channel migration structures and sustains riparian forms of data were used: aerial photography and field data. -

VOLCANIC INFLUENCE OVER FLUVIAL SEDIMENTATION in the CRETACEOUS Mcdermott MEMBER, ANIMAS FORMATION, SOUTHWESTERN COLORADO

VOLCANIC INFLUENCE OVER FLUVIAL SEDIMENTATION IN THE CRETACEOUS McDERMOTT MEMBER, ANIMAS FORMATION, SOUTHWESTERN COLORADO Colleen O’Shea A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE August: 2009 Committee: James Evans, advisor Kurt Panter, co-advisor John Farver ii Abstract James Evans, advisor Volcanic processes during and after an eruption can impact adjacent fluvial systems by high influx rates of volcaniclastic sediment, drainage disruption, formation and failure of natural dams, changes in channel geometry and changes in channel pattern. Depending on the magnitude and frequency of disruptive events, the fluvial system might “recover” over a period of years or might change to some other morphology. The goal of this study is to evaluate the preservation potential of volcanic features in the fluvial environment and assess fluvial system recovery in a probable ancient analog of a fluvial-volcanic system. The McDermott Member is the lower member of the Late Cretaceous - Tertiary Animas Formation in SW Colorado. Field studies were based on a southwest-northeast transect of six measured sections near Durango, Colorado. In the field, 13 lithofacies have been identified including various types of sandstones, conglomerates, and mudrocks interbedded with lahars, mildly reworked tuff, and primary pyroclastic units. Subsequent microfacies analysis suggests the lahar lithofacies can be subdivided into three types based on clast composition and matrix color, this might indicate different volcanic sources or sequential changes in the volcanic center. In addition, microfacies analysis of the primary pyroclastic units suggests both surge and block-and-ash types are present. -

Defining the Moment of Erosion

Earth Surface Processes and Landforms EarthDefining Surf. the Process. moment Landforms of erosion 30, 1597–1615 (2005) 1597 Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/esp.1234 Defining the moment of erosion: the principle of thermal consonance timing D. M. Lawler* School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, The University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK *Correspondence to: Abstract D. M. Lawler, School of Geography, Earth and Geomorphological process research demands quantitative information on erosion and deposi- Environmental Sciences, tion event timing and magnitude, in relation to fluctuations in the suspected driving forces. University of Birmingham, This paper establishes a new measurement principle – thermal consonance timing (TCT) Birmingham B15 2TT. – which delivers clearer, more continuous and quantitative information on erosion and E-mail: [email protected] deposition event magnitude, timing and frequency, to assist understanding of the controlling mechanisms. TCT is based on monitoring the switch from characteristically strong tempera- ture gradients in sediment, to weaker gradients in air or water, which reveals the moment of erosion. The paper (1) derives the TCT principle from soil micrometeorological theory; (2) illustrates initial concept operationalization for field and laboratory use; (3) presents experimental data for simple soil erosion simulations; and (4) discusses initial application of TCT and perifluvial micrometeorology principles in the delivery of timing solutions for two bank erosion events on the River Wharfe, UK, in relation to the hydrograph. River bank thermal regimes respond, as soil temperature and energy balance theory pre- dicts, with strong horizontal thermal gradients (often >>>1Kcm−−−1 over 6·8 cm). -

Classifying Rivers - Three Stages of River Development

Classifying Rivers - Three Stages of River Development River Characteristics - Sediment Transport - River Velocity - Terminology The illustrations below represent the 3 general classifications into which rivers are placed according to specific characteristics. These categories are: Youthful, Mature and Old Age. A Rejuvenated River, one with a gradient that is raised by the earth's movement, can be an old age river that returns to a Youthful State, and which repeats the cycle of stages once again. A brief overview of each stage of river development begins after the images. A list of pertinent vocabulary appears at the bottom of this document. You may wish to consult it so that you will be aware of terminology used in the descriptive text that follows. Characteristics found in the 3 Stages of River Development: L. Immoor 2006 Geoteach.com 1 Youthful River: Perhaps the most dynamic of all rivers is a Youthful River. Rafters seeking an exciting ride will surely gravitate towards a young river for their recreational thrills. Characteristically youthful rivers are found at higher elevations, in mountainous areas, where the slope of the land is steeper. Water that flows over such a landscape will flow very fast. Youthful rivers can be a tributary of a larger and older river, hundreds of miles away and, in fact, they may be close to the headwaters (the beginning) of that larger river. Upon observation of a Youthful River, here is what one might see: 1. The river flowing down a steep gradient (slope). 2. The channel is deeper than it is wide and V-shaped due to downcutting rather than lateral (side-to-side) erosion. -

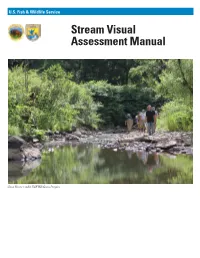

Stream Visual Assessment Manual

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Stream Visual Assessment Manual Cane River, credit USFWS/Gary Peeples U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Conasauga River, credit USFWS Table of Contents Introduction ..............................................................................................................................1 What is a Stream? .............................................................................................................1 What Makes a Stream “Healthy”? .................................................................................1 Pollution Types and How Pollutants are Harmful ........................................................1 What is a “Reach”? ...........................................................................................................1 Using This Protocol..................................................................................................................2 Reach Identification ..........................................................................................................2 Context for Use of this Guide .................................................................................................2 Assessment ........................................................................................................................3 Scoring Details ..................................................................................................................4 Channel Conditions ...........................................................................................................4 -

Drainage Basin Morphology in the Central Coast Range of Oregon

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF WENDY ADAMS NIEM for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in GEOGRAPHY presented on July 21, 1976 Title: DRAINAGE BASIN MORPHOLOGY IN THE CENTRAL COAST RANGE OF OREGON Abstract approved: Redacted for privacy Dr. James F. Lahey / The four major streams of the central Coast Range of Oregon are: the westward-flowing Siletz and Yaquina Rivers and the eastward-flowing Luckiamute and Marys Rivers. These fifth- and sixth-order streams conform to the laws of drain- age composition of R. E. Horton. The drainage densities and texture ratios calculated for these streams indicate coarse to medium texture compa- rable to basins in the Carboniferous sandstones of the Appalachian Plateau in Pennsylvania. Little variation in the values of these parameters occurs between basins on igneous rook and basins on sedimentary rock. The length of overland flow ranges from approximately i mile to i mile. Two thousand eight hundred twenty-five to 6,140 square feet are necessary to support one foot of channel in the central Coast Range. Maximum elevation in the area is 4,097 feet at Marys Peak which is the highest point in the Oregon Coast Range. The average elevation of summits in the thesis area is ap- proximately 1500 feet. The calculated relief ratios for the Siletz, Yaquina, Marys, and Luckiamute Rivers are compara- ble to relief ratios of streams on the Gulf and Atlantic coastal plains and on the Appalachian Piedmont. Coast Range streams respond quickly to increased rain- fall, and runoff is rapid. The Siletz has the largest an- nual discharge and the highest sustained discharge during the dry summer months. -

Modification of Meander Migration by Bank Failures

JournalofGeophysicalResearch: EarthSurface RESEARCH ARTICLE Modification of meander migration by bank failures 10.1002/2013JF002952 D. Motta1, E. J. Langendoen2,J.D.Abad3, and M. H. García1 Key Points: 1Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois, USA, • Cantilever failure impacts migration 2National Sedimentation Laboratory, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Oxford, Mississippi, through horizontal/vertical floodplain 3 material heterogeneity USA, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA • Planar failure in low-cohesion floodplain materials can affect meander evolution Abstract Meander migration and planform evolution depend on the resistance to erosion of the • Stratigraphy of the floodplain floodplain materials. To date, research to quantify meandering river adjustment has largely focused on materials can significantly affect meander evolution resistance to erosion properties that vary horizontally. This paper evaluates the combined effect of horizontal and vertical floodplain material heterogeneity on meander migration by simulating fluvial Correspondence to: erosion and cantilever and planar bank mass failure processes responsible for bank retreat. The impact of D. Motta, stream bank failures on meander migration is conceptualized in our RVR Meander model through a bank [email protected] armoring factor associated with the dynamics of slump blocks produced by cantilever and planar failures. Simulation periods smaller than the time to cutoff are considered, such that all planform complexity is Citation: caused by bank erosion processes and floodplain heterogeneity and not by cutoff dynamics. Cantilever Motta, D., E. J. Langendoen, J. D. Abad, failure continuously affects meander migration, because it is primarily controlled by the fluvial erosion at and M. -

Streams and Running Water Streams Are Part of the Hydrologic Cycle (Figure 10.1)

Streams and Running Water Streams are part of the hydrologic cycle (Figure 10.1) Stream: body of running water that is confined in a channel and moves downhill under the influence of gravity. Cross-section of a typical stream (Figure 10.2) 1) Channel Flow 2) Sheet Flow Drainage Basin: area of a stream and its’ tributaries. Tributary: small stream flowing into a large one. Divide: ridge seperating drainage basins. Drainage Patterns 1) Dendritic: resembles tree branches > occurs on uniformly resistant rock 2) Radial: streams diverge outward from a central point > occurs on conic shapes, like volcanoes 3) Rectangular: steams have sharp bends ¾ due to presence of faulting, river follows the fault 4) Trellis: Parallel main streams with right angle tributaries > occurs on valley and ridge geomorphologies Factors Affecting Stream Erosion and Deposition 1) Velocity = distance/time Fast = 5km/hr or 3mi/hr Flood = 25 km/hr or 15 mi/hr Figure 10.6: Fastest in the middle of the channel a) Gradient: downhill slope of the bed of the stream ¾ very high near the mountains ¾ 50-200 feet/ mile in highlands, 0.5 ft/mile in floodplain b) Channel Shape and Roughness (Friction) > Figure 10.9 ¾ Lots of fine particles – low roughness, faster river ¾ Lots of big particles – high roughness, slower river (more friction) High Velocity = erosion (upstream) Low Velocity = deposition (downstream) Figure 10.7 > Hjulstrom Diagram What do these lines represent? Salt and clay are hard to erode, and typically stay suspended 2) Discharge: amount of flow Q = width x depth -

East Osage River Watershed Inventory and Assessment

EAST OSAGE RIVER WATERSHED INVENTORY AND ASSESSMENT Prepared by Alex L. S. Schubert Missouri Department of Conservation West Central Region-Fisheries Division Clinton, MO November 30, 2001 Acknowledgments Thank you's are in order to numerous individuals who provided assistance on this document. Thanks to Mike Bayless and Tom Groshens for information gathering and the compilation of numerous tables, and to Ron Dent for his guidance on, and editing of early drafts of this document. Mike was also a tremendous help in getting me started and making final changes to this document. Thanks to Bill Turner for the guidance he provided throughout this process. Thanks to Mark Caldwell for assistance with ArcView GIS software, his assistance in the field, and his dedication to providing the best data and information possible in GIS format. Thanks to Del Lobb for extensive help throughout the draft process. Thanks also to Missouri Department of Conservation, Missouri Department of Natural Resources, Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and U.S. Geological Survey personnel and to other contributors too numerous to mention. Executive Summary The East Osage River Basin is found in central Missouri in the Missouri counties of Osage, Maries, Cole, Pulaski, Miller, Camden, Morgan, Benton, and Hickory and encompasses 2,474.52 mi2. This basin has been divided into two 8-digit hydrologic units (HUCs) and fourteen 11-digit HUCs. Lake of the Ozarks was formed in 1931 in the western half of the East Osage River Basin. Geomorphology This basin lies within a dissected plateau known as the Salem Plateau and is represented by four of Missouri’s natural divisions. -

Fluvial Geomorphic Assessment of the South River Watershed, MA

Fluvial Geomorphic Assessment of the South River Watershed, MA Prepared for Franklin Regional Council of Governments Greenfield, MA South River Prepared by John Field Field Geology Services Farmington, ME February 2013 South River geomorphic assessment - February 2013 Page 2 of 108 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 6 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 8 2.0 FLUVIAL GEOMORPHIC ASSESSMENT ............................................................... 8 2.1 Reach and segment delineation ................................................................................. 9 2.2 Review of existing studies ...................................................................................... 10 2.3 Watershed characterization ..................................................................................... 11 2.4 Historical aerial photographs and topographic maps .............................................. 12 2.5 Mapping of channel features ................................................................................... 13 2.5a Mill dams and impoundment sediments ............................................................ 14 2.5b Bar deposition ................................................................................................... 15 2.5c Bank erosion, mass wasting, and bank armoring ............................................. 15 2.5c Wood -

Us Department of the Interior Us Geological Survey

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY QUATERNARY GEOLOGY OF THE GRANITE PARK AREA, GRAND CANYON, ARIZONA: AGGRADATION-DOWNCUTTING CYCLES, CALIBRATION OF SOILS STAGES, AND RESPONSE OF FLUVIAL SYSTEM TO VOLCANIC ACTIVITY By Ivo Lucchitta1 , G.H. Curtis2, M.E. Davis3, S.W. Davis3, and Brent Turrin4. With an Appendix by Christopher Coder, Grand Canyon National Park, Grand Canyon, AZ 86040 Open-file Report 95-591 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. J U.S. Geological Survey, Flagstaff, AZ 86001 2 Berkeley Geochronology Center, Berkeley, CA 94709 3 Davis2, Georgetown, CA 95634 4 U.S. Geological Survey, MenLo Park, CA 94025 nr ivv ^^^^t^^^^^'^S:^ ';;.; ;.:;. .../r. - '.''^.^.v*'' ^.vj v'""/^"i"%- 'JW" A- - - - -- - * GLEN CANYON ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES QUATERNARY GEOLOGY-GEOMORPHOLOGY PROGRAM REPORT 2 QUATERNARY GEOLOGY OF THE GRANITE PARK AREA, GRAND CANYON, ARIZONA: DOWNCUTTING- AGGRADATION CYCLES, CALIBRATION OF SOIL STAGES, AND RESPONSE OF FLUVIAL SYSTEM TO VOLCANIC ACTIVITY CONTENTS ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION PURPOSE METHODS RESULTS Geology and geomorphology Soils Geo chronology SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS Geochronology Geology and geomorphology Soils Soil-stage calibration Processes REFERENCES ACKOWLEDGMENTS APPENDICES A Synopsis of Granite Park Archeology B Representative Soil Profile Descriptions C Step-heating spectra, isochrons and sampling comments for 39Ar-40Ar age determinations on Black Ledge basalt flow, Granite Park area, Grand Canyon FIGURES PLATES AND FIGURES Plate 1. View at mile 207.5 Plate 2. View of section at mile 208.9 Figure 1.