Eastwood's Unforgiven As a Reading of the Odyssey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cancel Culture: Posthuman Hauntologies in Digital Rhetoric and the Latent Values of Virtual Community Networks

CANCEL CULTURE: POSTHUMAN HAUNTOLOGIES IN DIGITAL RHETORIC AND THE LATENT VALUES OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITY NETWORKS By Austin Michael Hooks Heather Palmer Rik Hunter Associate Professor of English Associate Professor of English (Chair) (Committee Member) Matthew Guy Associate Professor of English (Committee Member) CANCEL CULTURE: POSTHUMAN HAUNTOLOGIES IN DIGITAL RHETORIC AND THE LATENT VALUES OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITY NETWORKS By Austin Michael Hooks A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of English The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee August 2020 ii Copyright © 2020 By Austin Michael Hooks All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT This study explores how modern epideictic practices enact latent community values by analyzing modern call-out culture, a form of public shaming that aims to hold individuals responsible for perceived politically incorrect behavior via social media, and cancel culture, a boycott of such behavior and a variant of call-out culture. As a result, this thesis is mainly concerned with the capacity of words, iterated within the archive of social media, to haunt us— both culturally and informatically. Through hauntology, this study hopes to understand a modern discourse community that is bound by an epideictic framework that specializes in the deconstruction of the individual’s ethos via the constant demonization and incitement of past, current, and possible social media expressions. The primary goal of this study is to understand how these practices function within a capitalistic framework and mirror the performativity of capital by reducing affective human interactions to that of a transaction. -

T Urnerarrives New Bill to Revive 4-Year Alien

Micronesia’s Leading Newspaper Since 1972 Vol. 22 No. 80 ; ' · ■/·"■ Saipan, MP 96950 ©1993 Marianas Variety Môndiiÿ ■ July 5 > Serving CNMI for 20 Years . T u r n e r a r r i v e s ASSISTANT Interior Secretary for Turner came from a three-day Territorial and International Af visit to Hawaii, where she met fairs Leslie Turner arrived Satur with Governor John Waihee and day for a series of meetings local officials of the US Navy’s re officials. gional command stationed in Turner will also visit of Saipan Honolulu. garment factories after a scheduled Early yesterday, Turner Joined luncheon meeting with Tinian Governor Lorenzo I. DL. Mayor James Mendiola and other Guerrero and other officials in Tinian officials. celebrating the 49th anniversary ASSISTANT Interior Secretary Leslie Turner (center) views Liberation Day parade with First Lady Matilda She is then scheduled to fly to of Liberation Day. Guerrero and Lt. Gov. Benjamin T. Manglona yesterday. Rota for a luncheon meeting with By 2 p.m. that same day, Turner Rota officials Tuesday after which will start her tour of garment fac she will go to Guam and Palau, and tories prior to an evening recep back to Honolulu, her first stop in tion to be hosted by Governor Tan issues reminder on PL 8-11 her 13-day Pacific island tour. Guerrero. (RHA) WHILE it is not a violation of the administrators and chiefs. after working hours, if it came law for a political to send cam The memorandum dated June from a government employee in a paign materials to government 17 invited all agency heads to a supervisory position. -

Songs by Artist 08/29/21

Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Alexander’s Ragtime Band DK−M02−244 All Of Me PM−XK−10−08 Aloha ’Oe SC−2419−04 Alphabet Song KV−354−96 Amazing Grace DK−M02−722 KV−354−80 America (My Country, ’Tis Of Thee) ASK−PAT−01 America The Beautiful ASK−PAT−02 Anchors Aweigh ASK−PAT−03 Angelitos Negros {Spanish} MM−6166−13 Au Clair De La Lune {French} KV−355−68 Auld Lang Syne SC−2430−07 LP−203−A−01 DK−M02−260 THMX−01−03 Auprès De Ma Blonde {French} KV−355−79 Autumn Leaves SBI−G208−41 Baby Face LP−203−B−07 Beer Barrel Polka (Roll Out The Barrel) DK−3070−13 MM−6189−07 Beyond The Sunset DK−77−16 Bill Bailey, Won’t You Please Come Home? DK−M02−240 CB−5039−3−13 B−I−N−G−O CB−DEMO−12 Caisson Song ASK−PAT−05 Clementine DK−M02−234 Come Rain Or Come Shine SAVP−37−06 Cotton Fields DK−2034−04 Cry Like A Baby LAS−06−B−06 Crying In The Rain LAS−06−B−09 Danny Boy DK−M02−704 DK−70−16 CB−5039−2−15 Day By Day DK−77−13 Deep In The Heart Of Texas DK−M02−245 Dixie DK−2034−05 ASK−PAT−06 Do Your Ears Hang Low PM−XK−04−07 Down By The Riverside DK−3070−11 Down In My Heart CB−5039−2−06 Down In The Valley CB−5039−2−01 For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow CB−5039−2−07 Frère Jacques {English−French} CB−E9−30−01 Girl From Ipanema PM−XK−10−04 God Save The Queen KV−355−72 Green Grass Grows PM−XK−04−06 − 1 − Songs by Artist 09/24/21 As Sung By Song Title Track # Greensleeves DK−M02−235 KV−355−67 Happy Birthday To You DK−M02−706 CB−5039−2−03 SAVP−01−19 Happy Days Are Here Again CB−5039−1−01 Hava Nagilah {Hebrew−English} MM−6110−06 He’s Got The Whole World In His Hands -

Compound AABA Form and Style Distinction in Heavy Metal *

Compound AABA Form and Style Distinction in Heavy Metal * Stephen S. Hudson NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.21.27.1/mto.21.27.1.hudson.php KEYWORDS: Heavy Metal, Formenlehre, Form Perception, Embodied Cognition, Corpus Study, Musical Meaning, Genre ABSTRACT: This article presents a new framework for analyzing compound AABA form in heavy metal music, inspired by normative theories of form in the Formenlehre tradition. A corpus study shows that a particular riff-based version of compound AABA, with a specific style of buildup intro (Aas 2015) and other characteristic features, is normative in mainstream styles of the metal genre. Within this norm, individual artists have their own strategies (Meyer 1989) for manifesting compound AABA form. These strategies afford stylistic distinctions between bands, so that differences in form can be said to signify aesthetic posing or social positioning—a different kind of signification than the programmatic or semantic communication that has been the focus of most existing music theory research in areas like topic theory or musical semiotics. This article concludes with an exploration of how these different formal strategies embody different qualities of physical movement or feelings of motion, arguing that in making stylistic distinctions and identifying with a particular subgenre or style, we imagine that these distinct ways of moving correlate with (sub)genre rhetoric and the physical stances of imagined communities of fans (Anderson 1983, Hill 2016). Received January 2020 Volume 27, Number 1, March 2021 Copyright © 2021 Society for Music Theory “Your favorite songs all sound the same — and that’s okay . -

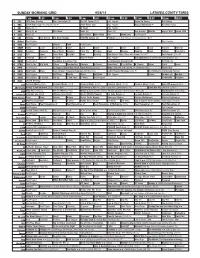

Sunday Morning Grid 9/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Tunnel to Towers Bull Riding 4 NBC 2014 Ryder Cup Final Day. (4) (N) Å 2014 Ryder Cup Paid Program Access Hollywood Å Red Bull Series 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Sea Rescue Wildlife Exped. Wild Exped. Wild 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Green Bay Packers at Chicago Bears. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Italy: Cities of Dreams (TVG) Å Over Hawai’i (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program The Specialist ›› (1994) Sylvester Stallone. (R) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) La Arrolladora Banda Limón Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue (2012) Baby’s Day Out ›› (1994) Joe Mantegna. -

Pro Wrestling Over -Sell

TTHHEE PPRROO WWRREESSTTLLIINNGG OOVVEERR--SSEELLLL™ a newsletter for those who want more Issue #1 Monthly Pro Wrestling Editorials & Analysis April 2011 For the 27th time... An in-depth look at WrestleMania XXVII Monthly Top of the card Underscore It's that time of year when we anything is responsible for getting Eddie Edwards captures ROH World begin to talk about the forthcoming WrestleMania past one million buys, WrestleMania, an event that is never it's going to be a combination of Tile in a shocker─ the story that makes the short of talking points. We speculate things. Maybe it'll be the appearances title change significant where it will rank on a long, storied list of stars from the Attitude Era of of highs and lows. We wonder what will wrestling mixed in with the newly Shocking, unexpected surprises seem happen on the show itself and gossip established stars that generate the to come few and far between, especially in the about our own ideas and theories. The need to see the pay-per-view. Perhaps year 2011. One of those moments happened on road to WreslteMania 27 has been a that selling point is the man that lit March 19 in the Manhattan Center of New York bumpy one filled with both anticipation the WrestleMania fire, The Rock. City. Eddie Edwards became the fifteenth Ring and discontent, elements that make the ─ So what match should go on of Honor World Champion after defeating April 3 spectacular in Atlanta one of the last? Oddly enough, that's a question Roderick Strong in what was described as an more newsworthy stories of the year. -

British Bulldogs, Behind SIGNATURE MOVE: F5 Rolled Into One Mass of Humanity

MEMBERS: David Heath (formerly known as Gangrel) BRODUS THE BROOD Edge & Christian, Matt & Jeff Hardy B BRITISH CLAY In 1998, a mystical force appeared in World Wrestling B HT: 6’7” WT: 375 lbs. Entertainment. Led by the David Heath, known in FROM: Planet Funk WWE as Gangrel, Edge & Christian BULLDOGS SIGNATURE MOVE: What the Funk? often entered into WWE events rising from underground surrounded by a circle of ames. They 1960 MEMBERS: Davey Boy Smith, Dynamite Kid As the only living, breathing, rompin’, crept to the ring as their leader sipped blood from his - COMBINED WT: 471 lbs. FROM: England stompin’, Funkasaurus in captivity, chalice and spit it out at the crowd. They often Brodus Clay brings a dangerous participated in bizarre rituals, intimidating and combination of domination and funk -69 frightening the weak. 2010 TITLE HISTORY with him each time he enters the ring. WORLD TAG TEAM Defeated Brutus Beefcake & Greg With the beautiful Naomi and Cameron Opponents were viewed as enemies from another CHAMPIONS Valentine on April 7, 1986 dancing at the big man’s side, it’s nearly world and often victims to their bloodbaths, which impossible not to smile when Clay occurred when the lights in the arena went out and a ▲ ▲ Behind the perfect combination of speed and power, the British makes his way to the ring. red light appeared. When the light came back the Bulldogs became one of the most popular tag teams of their time. victim was laying in the ring covered in blood. In early Clay’s opponents, however, have very Originally competing in promotions throughout Canada and Japan, 1999, they joined Undertaker’s Ministry of Darkness. -

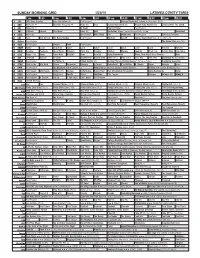

Sunday Morning Grid 1/25/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/25/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Indiana at Ohio State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Paid Detroit Auto Show (N) Mecum Auto Auction (N) Lindsey Vonn: The Climb 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Miami Heat at Chicago Bulls. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 700 Club Telethon 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Paid Program Big East Tip-Off College Basketball Duke at St. John’s. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program The Game Plan ›› (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Cold. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Aging Backwards Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Superman III ›› (1983) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Toluca República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Pink Floyd - Dark Side of the Moon Speak to Me Breathe on the Run Time the Great Gig in the Sky Money Us and Them Any Colour You Like Brain Damage Eclipse

Pink Floyd - Dark Side of the Moon Speak to Me Breathe On the Run Time The Great Gig in the Sky Money Us and Them Any Colour You Like Brain Damage Eclipse Pink Floyd – The Wall In the Flesh The Thin Ice Another Brick in the Wall (Part 1) The Happiest Days of our Lives Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2) Mother Goodbye Blue Sky Empty Spaces Young Lust Another Brick in the Wall (Part 3) Hey You Comfortably Numb Stop The Trial Run Like Hell Laser Queen Bicycle Race Don't Stop Me Now Another One Bites The Dust I Want To Break Free Under Pressure Killer Queen Bohemian Rhapsody Radio Gaga Princes Of The Universe The Show Must Go On 1 Laser Rush 2112 I. Overture II. The Temples of Syrinx III. Discovery IV. Presentation V. Oracle: The Dream VI. Soliloquy VII. Grand Finale A Passage to Bangkok The Twilight Zone Lessons Tears Something for Nothing Laser Radiohead Airbag The Bends You – DG High and Dry Packt like Sardine in a Crushd Tin Box Pyramid song Karma Police The National Anthem Paranoid Android Idioteque Laser Genesis Turn It On Again Invisible Touch Sledgehammer Tonight, Tonight, Tonight Land Of Confusion Mama Sussudio Follow You, Follow Me In The Air Tonight Abacab 2 Laser Zeppelin Song Remains the Same Over the Hills, and Far Away Good Times, Bad Times Immigrant Song No Quarter Black Dog Livin’, Lovin’ Maid Kashmir Stairway to Heaven Whole Lotta Love Rock - n - Roll Laser Green Day Welcome to Paradise She Longview Good Riddance Brainstew Jaded Minority Holiday BLVD of Broken Dreams American Idiot Laser U2 Where the Streets Have No Name I Will Follow Beautiful Day Sunday, Bloody Sunday October The Fly Mysterious Ways Pride (In the Name of Love) Zoo Station With or Without You Desire New Year’s Day 3 Laser Metallica For Whom the Bell Tolls Ain’t My Bitch One Fuel Nothing Else Matters Master of Puppets Unforgiven II Sad But True Enter Sandman Laser Beatles Magical Mystery Tour I Wanna Hold Your Hand Twist and Shout A Hard Day’s Night Nowhere Man Help! Yesterday Octopus’ Garden Revolution Sgt. -

101 Films for Filmmakers

101 (OR SO) FILMS FOR FILMMAKERS The purpose of this list is not to create an exhaustive list of every important film ever made or filmmaker who ever lived. That task would be impossible. The purpose is to create a succinct list of films and filmmakers that have had a major impact on filmmaking. A second purpose is to help contextualize films and filmmakers within the various film movements with which they are associated. The list is organized chronologically, with important film movements (e.g. Italian Neorealism, The French New Wave) inserted at the appropriate time. AFI (American Film Institute) Top 100 films are in blue (green if they were on the original 1998 list but were removed for the 10th anniversary list). Guidelines: 1. The majority of filmmakers will be represented by a single film (or two), often their first or first significant one. This does not mean that they made no other worthy films; rather the films listed tend to be monumental films that helped define a genre or period. For example, Arthur Penn made numerous notable films, but his 1967 Bonnie and Clyde ushered in the New Hollywood and changed filmmaking for the next two decades (or more). 2. Some filmmakers do have multiple films listed, but this tends to be reserved for filmmakers who are truly masters of the craft (e.g. Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick) or filmmakers whose careers have had a long span (e.g. Luis Buñuel, 1928-1977). A few filmmakers who re-invented themselves later in their careers (e.g. David Cronenberg–his early body horror and later psychological dramas) will have multiple films listed, representing each period of their careers. -

Guitar Hero® Metallica® Thrashes Its Way Into the Guitar Hero® Music Library

Guitar Hero® Metallica® Thrashes its Way Into the Guitar Hero® Music Library --For One Week Only, Buy Guitar Hero(R): Warriors of Rock and Import Your Guitar Hero(R) Metallica(R) Tracks for Free --Select Tracks From Guitar Hero(R) World Tour, Guitar Hero(R) Smash Hits, Guitar Hero (R) 5 and Band Hero(R) Also Importable Into This Fall's Guitar Hero: Warriors of Rock SANTA MONICA, Calif., Sept 14, 2010 /PRNewswire via COMTEX News Network/ -- Legendary musical icons and heavy metal pioneers, Metallica, are returning for an encore this fall by bringing their skill, intensity and passion to the Guitar Hero(R) music library. In conjunction with the launch of Guitar Hero(R): Warriors of Rock, fans who own Guitar Hero(R) Metallica(R) will be able to import 39 of the game's on-disc tracks directly into their Guitar Hero music library beginning September 28. Additionally, head-banging, guitar-shredding rockers who buy Guitar Hero: Warriors of Rock between September 28 and October 5 will be able to import these tracks from their copy of Guitar Hero Metallica for free*. The disc import will feature the following tracks: ● Bob Seger & the Silver Bullet Band - "Turn The Page (Live)" ● Diamond Head - "Am I Evil?" ● Kyuss - "Demon Cleaner" ● Lynyrd Skynyrd - "Tuesday's Gone" ● Machine Head - "Beautiful Mourning" ● Mastodon - "Blood & Thunder" ● Mercyful Fate - "Evil" ● Metallica - "Battery" ● Metallica - "Creeping Death" ● Metallica - "Disposable Heroes" ● Metallica - "Dyers Eve" ● Metallica - "Enter Sandman" ● Metallica - "Fade To Black" ● Metallica -

2020 WWE Transcendent

BASE ROSTER BASE CARD 1 Adam Cole NXT 2 Andre the Giant WWE Legend 3 Angelo Dawkins WWE 4 Bianca Belair NXT 5 Big Show WWE 6 Bruno Sammartino WWE Legend 7 Cain Velasquez WWE 8 Cameron Grimes WWE 9 Candice LeRae NXT 10 Chyna WWE Legend 11 Damian Priest NXT 12 Dusty Rhodes WWE Legend 13 Eddie Guerrero WWE Legend 14 Harley Race WWE Legend 15 Hulk Hogan WWE Legend 16 Io Shirai NXT 17 Jim "The Anvil" Neidhart WWE Legend 18 John Cena WWE 19 John Morrison WWE 20 Johnny Gargano WWE 21 Keith Lee NXT 22 Kevin Nash WWE Legend 23 Lana WWE 24 Lio Rush WWE 25 "Macho Man" Randy Savage WWE Legend 26 Mandy Rose WWE 27 "Mr. Perfect" Curt Hennig WWE Legend 28 Montez Ford WWE 29 Mustafa Ali WWE 30 Naomi WWE 31 Natalya WWE 32 Nikki Cross WWE 33 Paul Heyman WWE 34 "Ravishing" Rick Rude WWE Legend 35 Renee Young WWE 36 Rhea Ripley NXT 37 Robert Roode WWE 38 Roderick Strong NXT 39 "Rowdy" Roddy Piper WWE Legend 40 Rusev WWE 41 Scott Hall WWE Legend 42 Shorty G WWE 43 Sting WWE Legend 44 Sonya Deville WWE 45 The British Bulldog WWE Legend 46 The Rock WWE Legend 47 Ultimate Warrior WWE Legend 48 Undertaker WWE 49 Vader WWE Legend 50 Yokozuna WWE Legend AUTOGRAPH ROSTER AUTOGRAPHS A-AA Andrade WWE A-AB Aleister Black WWE A-AJ AJ Styles WWE A-AK Asuka WWE A-AX Alexa Bliss WWE A-BC King Corbin WWE A-BD Diesel WWE Legend A-BH Bret "Hit Man" Hart WWE Legend A-BI Brock Lesnar WWE A-BL Becky Lynch WWE A-BR Braun Strowman WWE A-BT Booker T WWE Legend A-BW "The Fiend" Bray Wyatt WWE A-BY Bayley WWE A-CF Charlotte Flair WWE A-CW Sheamus WWE A-DB Daniel Bryan WWE A-DR Drew