Organised Religion in Axminster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colyton Neighbourhood Plan Local Evidence Report Aug 2017

Colyton Parish Neighbourhood Plan Local Evidence Report August 2017 Introduction Neighbourhood planning policy and proposals need to be based on a proper understanding of the place they relate to, if it they are to be relevant, realistic and to address local issues effectively. It is important that our Neighbourhood Plan is based on robust information and analysis of the local area; this is called the evidence base. Unless policy is based on firm evidence and proper community engagement, then it is more likely to reflect the assumptions and prejudices of those writing it than to reflect the needs of the wider area and community. This report endeavours to bring together recent information and informed opinion about the Parish that may have some relevance in preparing a Colyton Neighbourhood Plan. Together with its companion document, which sets out the strategic framework in which we must prepare the Neighbourhood Plan, it provides us with a shared base of knowledge and understanding about Colyton parish on which we can build. Topics: Natural Environment Built Environment and Heritage Housing Community Services and Facilities Transport and Travel Local Economy Leisure and Recreation Compiled by: Carol Rapley Caroline Collier Colin Pady David Page Elaine Stratford Helen Parr Lucy Dack Robert Griffin Steve Real Steve Selby Maps in this report are reproduced under the Public Sector Mapping Agreement © Crown copyright [and database rights] (2016) OS license 100057548 Colyton NP Local Evidence Base 2 Natural Environment Introduction Colyton Parish comprises some 10 square miles (6,400 acres) in area and is situated in East Devon- 2 miles inland. -

Uplyme Neighbourhood Plan 2017-2031

Uplyme Neighbourhood Plan Uplyme Neighbourhood Plan 2017-2031 Uplyme Parish Council July 2017 Uplyme village centre seen from Horseman's Hill Page 1 of 62 July 2017 Uplyme Neighbourhood Plan Foreword Welcome to the Uplyme Neighbourhood Plan! Neighbourhood Development Plans were introduced by the 2011 Localism Act, to give local people more say about the scale and nature of development in their area, within the context of both strategic planning policy in the National Planning Policy Framework 2012, and local plans – in our case, the adopted East Devon Local Plan 2013-2031. The Uplyme Neighbourhood Plan relates to the whole of the Parish and includes a wide range of topics: housing, employment, community facilities, transport, and the built and natural environment. The Plan will run until 2031 to coincide with the end date of the Local Plan, but may need to be reviewed before then. The Plan has been drafted by local people in the Uplyme Neighbourhood Plan Group, following extensive community consultation and engagement over a period of years, followed by an examination by an independent Planning Inspector. We believe that the plan represents a broad consensus of local opinion. Chris James Chair Uplyme Parish Council & Neighbourhood Plan Group July 2017 Dedication This Plan is dedicated to the memory of Peter Roy Whiting, former Chairman of both the Parish Council and the Neighbourhood Plan Group. Without his encyclopaedic technical knowledge of planning and civil engineering, his puckish wit, enthusiasm and dedication, the project would have struggled in its formative stage. Peter – your presence is sadly missed. Page 2 of 62 July 2017 Uplyme Neighbourhood Plan Conventions Policies in this Plan are included in blue-shaded boxes thus: The policy number and title are shown at the top The policy wording appears here as the main body. -

Excursion to Lyme Regis, Easter, 1906

320 EXCURSION TO LYME REGIS, EASTER, 1906. pebbles and bed NO.3 seemed, however, to be below their place. The succession seemed, however,to be as above, and, if that be so, the beds below bed I are probably Bagshot Beds. "The pit at the lower level has been already noticed in our Proceedings; cj. H. W. Monckton and R. S. Herries 'On some Bagshot Pebble Beds and Pebble Gravel,' Proc. Ceol. Assoc., vol. xi, p. 13, at p. 22. The pit has been worked farther back, and the clay is now in consequence thicker. Less of the under lying sand is exposed than it was in June, 1888. "The casts of shells which occur in this sand were not abundant, but several were found by members of the party on a small heap of sand at the bottom of the pit." Similarly disturbed strata were again observed in the excavation for the new reservoir close by. A few minutes were then profitably spent in examining Fryerning Church, and its carved Twelfth Century font, etc. At the Spread Eagle a welcome tea awaited the party, which, after thanking the Director, returned by the 7.55 p.m. train to London. REFERENCES. Geological Survey Map, Sheet 1 (Drift). 1889. WHITAKER, W.-I< Geology of London," vol. i, pp. 259, 266. &c. 1889. MONCKTON, H. W., and HERRIES, R. S.-I< On Some Bagshot Pebble Beds and Pebble Gravel," Proc, Geo], Assoc., vol, xi, p. 13. 1904. SALTER, A. E.-" On the Superficial Deposits of Central and Southern England," Proc. Ceo!. Assoc., vol. -

Here It Became Obvious That Hollacombe Crediton and Not Hollacombe Winkleigh Was Implied and Quite a Different Proposition

INTRODUCTION In 1876 Charles Worthy wrote “The History of the Manor and Church of Winkleigh”, the first and only book on Winkleigh to be published. Although this valuable little handbook contains many items of interest, not all of which fall within the range of its title, it is not a complete history and consequently fails to meet the requirements of the Devonshire Association. More than a dozen years ago a friend remarked to me that the monks of Crediton at one time used to walk to Hollacombe in order to preach at the ancient chapel of Hollacombe Barton. I was so surprised by this seemingly long trek that I made enquiries of the Devonshire Association. I was referred to the Tower Library of Crediton Church where it became obvious that Hollacombe Crediton and not Hollacombe Winkleigh was implied and quite a different proposition. Meantime the Honorary General Editor of the Parochial Section (Hugh R. Watkins Esq.) suggested that I should write a history of Winkleigh. The undertaking was accepted although it was clear that my only qualification for the task was a deep regard for the associations of the parish combined with a particularly intense love for the hamlet of Hollacombe. The result of this labour of love, produced in scanty spare time, and spread over the intervening years should be considered with these points in view. The proof of this present pudding will be measured by the ease with which the less immediately interesting parts can be assimilated by the general reader. Due care has been taken to verify all the subject matter. -

Diocese News March 20

SERVING WITH JOY GOOD NEWS FROM THE DIOCESE OF EXETER | march 2020 Reverend Nick Haigh talks about JOY 2020 Inside: and the need to engage with people outside JOY 2020 our church walls KEY DATES FAMILY FUN COOKING CLUB “We have been looking for and recipe cards for families to ways in which we can support pop in and collect for free during families in the holidays with food. the school holidays or at other “We talked to foodbanks and times of the year. schools and found out that A #familyfuncookingclub some families aren’t going to Instagram account has been foodbanks because that’s not set-up for families to share their what they do. culinary creations. “Others can’t get to them Tatiana says: “We are hoping because of the distance they Family Fun Cooking Club will have to travel. It’s preventing enable all families, wherever they them from accessing food for are in Devon, to access good The recipes include: Baked their families.” ingredients to cook a family meal Porridge, Lentil Dhal, Hot Dog Tatiana Wilson is the Education together.” Spaghetti, Green Pasta Bake Advisor for projects and For more information and to and Microwave Mug Cake. vulnerable pupils at the Church download recipe cards go to: Merenna says: “All the recipes of England in Devon. https://exeter.anglican.org/ have been developed using She has taken a pilot project resources/faith-action/family- really basic ingredients which from the West Exmoor Federation fun-cooking-club/ or email are readily available in shops and of schools in North Devon and [email protected] foodbanks. -

Westwood, Land Adjoining Junction 27 on M5, Mid Devon

WESTWOOD, LAND ADJOINING JUNCTION 27 ON M5, MID DEVON ARCHAEOLOGICAL DESK BASED ASSESSMENT Prepared for GL HEARN Mills Whipp Projects Ltd., 40, Bowling Green Lane, London EC1R 0NE 020 7415 7044 [email protected] October 2014 WESTWOOD, LAND ADJOINING JUNCTION 27 ON M5 ARCHAEOLOGICAL DESK BASED ASSESSMENT Contents 1. Introduction & site description 2. Report Specification 3. Planning Background 4. Archaeological & Historical Background 5. List of Heritage Assets 6. Landscape Character Assessment 7. Archaeological Assessment 8. Impact Assessment 9. Conclusions Appendix 1 Archaeological Gazetteer Appendix 2 Sources Consulted Figures Fig.1 Site Location Fig.2 Archaeological Background Fig.3 Saxton 1575 Fig.4 Donn 1765 Fig.5 Cary 1794 Fig.6 Ordnance Survey 1802 Fig.7 Ordnance Survey 1809 Fig.8 Ordnance Survey 1830 (Unions) Fig.9 Ordnance Survey 1850 (Parishes) Fig.10 Ordnance Survey 1890 Fig.11 Ordnance Survey 1906 Fig.12 Ordnance Survey 1945 (Landuse) Fig.13 Ordnance Survey 1962 Fig.14 Ordnance Survey 1970 Fig.15 Ordnance Survey 1993 Fig.16 Site Survey Plan 1. INTRODUCTION & SITE DESCRIPTION 1.1 Mills Whipp Projects has been commissioned by GL Hearn to prepare a Desk Based Assessment of archaeology for the Westwood site on the eastern side of Junction 27 of the M5 (Figs.1, 2 & 17). 1.2 The site is centred on National Grid Reference ST 0510 1382 and is approximately 90 ha (222 acres) in area. It lies immediately to the east of the Sampford Peverell Junction 27 of the M5. Its northern side lies adjacent to Higher Houndaller Farmhouse while the southern end is defined by Andrew’s Plantation, the lane leading to Mountstephen Farm and Mountstephen Cottages (Fig.16). -

DEVONSHIRE. [KELLY's Sliutlis,BLACKSMITHS &FARRIERS Con

880 SMI DEVONSHIRE. [KELLY'S SlIUTlIs,BLACKSMITHS &FARRIERS con. RichardsJ.BeerAlston,Roborough RS.O Stawt Damel, Horsebridge, Sydenham. Nott & Cornish, Chapel street, Tiverton Ridge Robt. Petrockstow,Beaford RS.O Damerel, Tavistock Oatway Hy.jun.Yarnscombe,Barnstaple RobertsJ.Brattn.Clovlly.LewDwn.RS.O Stear John, Loddiswell, Kingsbridge Oke William, Bradwortby, Holswortby RobertsJ.Brattn.Clovlly.LewDwn.RS.O Stear Philip, Cole's cross, Mounts R.S.() Oldridge Timothy, Seaton Roberts John, 3 Finewell st. Plymouth Steer George, Mill street, }'{ingsbridge Oliver Brothers, West.leigh, Bideford Roberts Thomas, Lew Down RS.O Steer Joseph, Lincombe, Ilfracombe Oliver James, Queen street, Barnstaple Robins Thomas, Hemyoek, Cullompton Stidwell James, Luffincott, Launceston OliveI' James B. Queen st. Barnstaple Rockett William, Whitford, Axminster Stoneman George, Shooting Marsh stile,. Osborn William, North Tawton R.S.O Rogers Thomas, Pinhoe, Exeter St. Thomas, Exeter Pady John, Colyton, Axminster Rottenbury R. Parracombe, Barnstaple Stott John, Chagford, Newton Abbot Paimer Lionel, Church lane, Torrington Rowland Fras. Virginstowe, Launceston Strawbridge R. Hemyock, Cullompton Parish John, Goodleigh, Barnstaple Rowland Richard, Lew Down RS.O Strawbridge Wm. Rawridge, Honiton Parnell Henry, Langdon, North Pether- Rundle Philip, Colebrook, Plympton Stuart E. Marsh gn. Rockbeare, l<:xeter win, Launeeston Rnndle Philip, Galmpton, Kingsbridge Stnart Mrs. Elizth. ~ockbeare, Exeter Parrett Henry, Branscombe, Sidmouth Rundle Thomas, Sampford Spiney, Hor- Stndley Henry, Castle hill, Axminster ParsonsJas.SydenhamDamerel,Tavistck rabridge RS.O Summers James, Membury, Chard Parsons John, Lyme street, Axminster Salter Henry, Talaton, Ottery SI. Mary Summers William, West Anstey, Dulver Patch William,Northmostown,Otterton, SampsonWm.Princess St.ope,Plymonth ton RS.O Ottery St. Mary Sandercock William, Clubworthy, North Surcombe John, Bridestowe R.8.0 Paul Mrs. -

Ferndale Cottage Whitford Road, Musbury, Axminster, Devon

Ferndale Cottage Whitford Road, Musbury, Axminster, Devon Ferndale Cottage, Whitford A fabulous, well presented attached two bedroom period cottage situated in a delightful Road, Musbury, Axminster, semi rural location, which is being sold with no onward chain. Devon, EX13 7AP Guide Price £210,000 Axminster: 3.5 miles. Seaton: 4.1 miles. Honiton: 9.4 miles DESCRIPTION On the first floor a hallway has doors will find the well known River Cottage towards Axminster. After passing This delightful cottage can currently be off to two double bedrooms. canteen and deli, the train station is on Kilmington, ignore the turning left found on Air B&B as an up and running The property further benefits from the main line to Exeter and to London towards Axminster, stay on the A35 for business with many of the features one UPVC double glazing and gas central Waterloo; the M5 and A303 are also a further 1/2 mile then take the next left would like to see such as exposed heating with radiators in all principle easily accessible. It is only 3 miles signposted Musbury/ Seaton. At the T beams, thick walls and views across rooms. from the town of Colyton with the junction turn left onto the A358 towards open countryside. renowned Colyton Grammar School, Seaton and follow the road for 2 miles. SITUATION one of the highest ranked schools in Upon entering Musbury take the right The accommodation includes on the Musbury is a pretty East Devon village the country. The picturesque Jurassic hand turn at the T junction (by the ground floor, a charming living room situated in an Area of Outstanding coast is nearby at Beer, Branscombe Golden Hind public house) into with Charnwood wood-burning stove in Natural Beauty. -

Draft Scheme and a Glossary of All Terms Used

Revd Dr Adrian Hough Exeter Diocesan Mission and Pastoral Secretary The Old Deanery Exeter EX1 1HS 01392 294910 [email protected] 22nd October 2020 Mission and Pastoral Measure 2011 Diocese of Exeter The Benefice of Honiton, Gittisham, Combe Raleigh, Monkton, Awliscombe and Buckerell The Benefice of Offwell, Northleigh, Farway, Cotleigh and Widworthy The Benefice of Colyton, Musbury, Southleigh and Branscombe The Benefice of Broadhembury, Dunkeswell, Luppitt, Plymtree, Sheldon, and Upottery The Bishop of Exeter has asked me to publish a draft Pastoral Scheme in respect of pastoral proposals affecting the above parishes. I attach a copy of the draft Scheme and a glossary of all terms used. I am sending a copy to all the statutory interested parties, as the Mission and Pastoral Measure requires, and any others with an interest in the proposals. Anyone may make representations for or against all or any part or parts of the Draft Scheme and should send them so as to reach the Church Commissioners at the following address no later than midnight on Monday 7th December 2020. Rex Andrew Church Commissioners Church House Great Smith Street London SW1P 3AZ (email [email protected]) (tel 020 7898 1743) Representations may be sent by post or e-mail (although e-mail is preferable at present) and should be accompanied by a statement of your reasons for making the representation. If the Church Commissioners have not acknowledged receipt of your representation before the above date, please ring or e-mail them to ensure it has been received. For administrative purposes, a petition will be classed as a single representation and they will only correspond with the sender of the petition, if known, or otherwise the first signatory – “the primary petitioner”. -

Environment Agency South West Region

ENVIRONMENT AGENCY SOUTH WEST REGION 1997 ANNUAL HYDROMETRIC REPORT Environment Agency Manley House, Kestrel Way Sowton Industrial Estate Exeter EX2 7LQ Tel 01392 444000 Fax 01392 444238 GTN 7-24-X 1000 Foreword The 1997 Hydrometric Report is the third document of its kind to be produced since the formation of the Environment Agency (South West Region) from the National Rivers Authority, Her Majesty Inspectorate of Pollution and Waste Regulation Authorities. The document is the fourth in a series of reports produced on an annua! basis when all available data for the year has been archived. The principal purpose of the report is to increase the awareness of the hydrometry within the South West Region through listing the current and historic hydrometric networks, key hydrometric staff contacts, what data is available and the reporting options available to users. If you have any comments regarding the content or format of this report then please direct these to the Regional Hydrometric Section at Exeter. A questionnaire is attached to collate your views on the annual hydrometric report. Your time in filling in the questionnaire is appreciated. ENVIRONMENT AGENCY Contents Page number 1.1 Introduction.............................. .................................................... ........-................1 1.2 Hydrometric staff contacts.................................................................................. 2 1.3 South West Region hydrometric network overview......................................3 2.1 Hydrological summary: overview -

Chardstock Baptisms to 1879

CHARDSTOCK ST. ANDREWS CHURCH - BAPTISMS Source: Chardstock Parish Registers and Bishop’s Transcripts Dates: 1579 to 1582 from Bishop’s Transcripts 1597 to 1846 transcripts from Parish Registers, except periods March 1707 to April 1713, July 1713 to August 1714 and August 1714 to June 1716 for which no records are available. 1847 to 1879 transcripts have been taken from photocopies of the Bishop’s Transcripts of the Chardstock Parish Registers, held in Wiltshire Records Office. Where these were unclear, they have been checked against microfiches of the originals, held in Devon Records Office, and altered as appropriate. There are a number of inconsistencies between the two versions; for instance Susan Cozins in the Bishop’s Transcript appears as Susan Cousins in the Parish Register. The Wiltshire records for years 1850, 1856, 1858 1862, 1864, 1865, 1868, 1871, 1873 and 1876 are missing, either because they were not copied originally or because they have been lost. These gaps have been made good from the Devon Records Office, and are included within this transcript. Both Parish Registers and Bishop’s Transcripts are given for the years 1847, 1848, 1849 and 1850. The researcher is strongly advised to consult the original copies at Wiltshire or Devon Record Office, and use these transcriptions only as a guide to what these sources contain. When using this site, the following points should also be borne in mind: Abbreviations have been avoided wherever possible and full stops have not been used in names, thus Wm C. Watts in the register appears as William C Watts. This measure is designed to assist word search software programmes. -

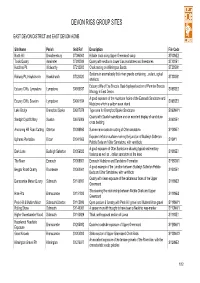

Devon Rigs Group Sites Table

DEVON RIGS GROUP SITES EAST DEVON DISTRICT and EAST DEVON AONB Site Name Parish Grid Ref Description File Code North Hill Broadhembury ST096063 Hillside track along Upper Greensand scarp ST00NE2 Tolcis Quarry Axminster ST280009 Quarry with section in Lower Lias mudstones and limestones ST20SE1 Hutchins Pit Widworthy ST212003 Chalk resting on Wilmington Sands ST20SW1 Sections in anomalously thick river gravels containing eolian ogical Railway Pit, Hawkchurch Hawkchurch ST326020 ST30SW1 artefacts Estuary cliffs of Exe Breccia. Best displayed section of Permian Breccia Estuary Cliffs, Lympstone Lympstone SX988837 SX98SE2 lithology in East Devon. A good exposure of the mudstone facies of the Exmouth Sandstone and Estuary Cliffs, Sowden Lympstone SX991834 SX98SE3 Mudstone which is seldom seen inland Lake Bridge Brampford Speke SX927978 Type area for Brampford Speke Sandstone SX99NW1 Quarry with Dawlish sandstone and an excellent display of sand dune Sandpit Clyst St.Mary Sowton SX975909 SX99SE1 cross bedding Anchoring Hill Road Cutting Otterton SY088860 Sunken-lane roadside cutting of Otter sandstone. SY08NE1 Exposed deflation surface marking the junction of Budleigh Salterton Uphams Plantation Bicton SY041866 SY0W1 Pebble Beds and Otter Sandstone, with ventifacts A good exposure of Otter Sandstone showing typical sedimentary Dark Lane Budleigh Salterton SY056823 SY08SE1 features as well as eolian sandstone at the base The Maer Exmouth SY008801 Exmouth Mudstone and Sandstone Formation SY08SW1 A good example of the junction between Budleigh