Teodor Mateoc Editor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solar Writer Report for Abraham Lincoln

FIXED STARS A Solar Writer Report for Abraham Lincoln Written by Diana K Rosenberg Compliments of:- Stephanie Johnson Seeing With Stars Astrology PO Box 159 Stepney SA 5069 Australia Tel/Fax: +61 (08) 8331 3057 Email: [email protected] Web: www.esotech.com.au Page 2 Abraham Lincoln Natal Chart 12 Feb 1809 12:40:56 PM UT +0:00 near Hodgenville 37°N35' 085°W45' Tropical Placidus 22' 13° 08°ˆ ‡ 17' ¾ 06' À ¿É ‰ 03° ¼ 09° 00° 06° 09°06° ˆ ˆ ‡ † ‡ 25° 16' 41'08' 40' † 01' 09' Œ 29' ‰ 9 10 23° ¶ 8 27°‰ 11 Ï 27° 01' ‘ ‰02' á 7 12 ‘ áá 23° á 23° ¸ 23°Š27' á Š à „ 28' 28' 6 18' 1 10°‹ º ‹37' 13° 05' ‹ 5 Á 22° ½ 27' 2 4 01' Ü 3 07° Œ ƒ » 09' 23° 09° Ý Ü 06° 16' 06' Ê 00°ƒ 13° 22' Ý 17' 08°‚ Page 23 Astrological Summary Chart Point Positions: Abraham Lincoln Planet Sign Position House Comment The Moon Capricorn 27°Cp01' 12th The Sun Aquarius 23°Aq27' 12th read into 1st House Mercury Pisces 10°Pi18' 1st Venus Aries 7°Ar27' 1st read into 2nd House Mars Libra 25°Li29' 8th Jupiter Pisces 22°Pi05' 1st Saturn Sagittarius 3°Sg08' 9th read into 10th House Uranus Scorpio 9°Sc40' 8th Neptune Sagittarius 6°Sg41' 9th read into 10th House Pluto Pisces 13°Pi37' 1st The North Node Scorpio 6°Sc09' 8th The South Node Taurus 6°Ta09' 2nd The Ascendant Aquarius 23°Aq28' 1st The Midheaven Sagittarius 8°Sg22' 10th The Part of Fortune Capricorn 27°Cp02' 12th Chart Point Aspects Planet Aspect Planet Orb App/Sep The Moon Square Mars 1°32' Separating The Moon Conjunction The Part of Fortune 0°00' Applying The Sun Trine Mars 2°02' Applying The Sun Conjunction The Ascendant -

The Blue Planet Report from Stellafane Perspective on Apollo How to Gain and Retain New Members

Published by the Astronomical League Vol. 71, No. 4 September 2019 THE BLUE PLANET REPORT FROM STELLAFANE 7.20.69 5 PERSPECTIVE ON APOLLO YEARS APOLLO 11 HOW TO GAIN AND RETAIN NEW MEMBERS mic Hunter h Cos h 4 er’s 5 t h Win 6 7h +30° AURIG A +30° Fast Facts TAURUS Orion +20° χ1 χ2 +20° GE MIN I ated winter nights are domin ο1 Mid ξ ν 2 ORIO N ο tion Orion. This +10° by the constella 1 a π Meiss λ 2 μ π +10° 2 φ1 attended by his φ 3 unter, α γ π cosmic h Bellatrix 4 Betelgeuse π d ω Canis Major an ψ ρ π5 hunting dogs, π6 0° intaka aurus the M78 δ M , follows T 0° ε and Minor Alnitak Alnilam What’s Your Pleasure? ζ h σ η vens eac EROS ross the hea MONOC M43 M42 Bull ac θ τ ι υ ess pursuit. β –10° night in endl Saiph Rigel –10° κ The showpiece of the ANI S C LEPU S ERIDANU S ion MAJOR constellation is the Or ORION (Constellation) –20° wn here), –20° Nebula (M42,sho ion 5 hr; Location: Right Ascens a region of nebulosity ° north 4h Declination 5 5h 6h 7h 2 square degrees th just 1,300 a: 594 and starbir Are 3 4 5 6 0 1 2 0 -2 -1 he Hunter 2 Symbol: T 0 t-years away that is M42 (Orion Nebula); C ligh Notable Objects: a la); NG C 2024 laked eye as a tary nebu e M78 (plane visible to the n n la) d. -

GTO Keypad Manual, V5.001

ASTRO-PHYSICS GTO KEYPAD Version v5.xxx Please read the manual even if you are familiar with previous keypad versions Flash RAM Updates Keypad Java updates can be accomplished through the Internet. Check our web site www.astro-physics.com/software-updates/ November 11, 2020 ASTRO-PHYSICS KEYPAD MANUAL FOR MACH2GTO Version 5.xxx November 11, 2020 ABOUT THIS MANUAL 4 REQUIREMENTS 5 What Mount Control Box Do I Need? 5 Can I Upgrade My Present Keypad? 5 GTO KEYPAD 6 Layout and Buttons of the Keypad 6 Vacuum Fluorescent Display 6 N-S-E-W Directional Buttons 6 STOP Button 6 <PREV and NEXT> Buttons 7 Number Buttons 7 GOTO Button 7 ± Button 7 MENU / ESC Button 7 RECAL and NEXT> Buttons Pressed Simultaneously 7 ENT Button 7 Retractable Hanger 7 Keypad Protector 8 Keypad Care and Warranty 8 Warranty 8 Keypad Battery for 512K Memory Boards 8 Cleaning Red Keypad Display 8 Temperature Ratings 8 Environmental Recommendation 8 GETTING STARTED – DO THIS AT HOME, IF POSSIBLE 9 Set Up your Mount and Cable Connections 9 Gather Basic Information 9 Enter Your Location, Time and Date 9 Set Up Your Mount in the Field 10 Polar Alignment 10 Mach2GTO Daytime Alignment Routine 10 KEYPAD START UP SEQUENCE FOR NEW SETUPS OR SETUP IN NEW LOCATION 11 Assemble Your Mount 11 Startup Sequence 11 Location 11 Select Existing Location 11 Set Up New Location 11 Date and Time 12 Additional Information 12 KEYPAD START UP SEQUENCE FOR MOUNTS USED AT THE SAME LOCATION WITHOUT A COMPUTER 13 KEYPAD START UP SEQUENCE FOR COMPUTER CONTROLLED MOUNTS 14 1 OBJECTS MENU – HAVE SOME FUN! -

The Blue Planet Report from Stellafane Perspective on Apollo How to Gain and Retain New Members

Published by the Astronomical League Vol. 71, No. 4 September 2019 THE BLUE PLANET REPORT FROM STELLAFANE 7.20.69 5 PERSPECTIVE ON APOLLO YEARS APOLLO 11 HOW TO GAIN AND RETAIN NEW MEMBERS What’s Your Pleasure? From Famous Observatories to Solar Eclipse Take Your Pick From These Tours Travel Down Under to visit top Australian Observatories observatories, including Siding October 1–9, 2019 Spring and “The Dish” at Parkes. Go wine-tasting, hike in nature reserves, and explore eclectic Syd- ney and Australia’s capital, Can- berra. Plus: Stargaze under south- ern skies. Options to Great Barrier Reef and Uluru or Ayers Rock. skyandtelescope.com/australia2019 Uluru & Sydney Opera House: Tourism Australia; observatory: Winton Gibson Astronomy Across Italy May 3–11, 2020 As you travel in comfort from Rome to Florence, Pisa, and Padua, visit the Vatican Observatory, the Galileo Museum, Arcetri Observatory, and more. Enjoy fine food, hotels, and other classic Italian treats. Extensions in Rome and Venice available. skyandtelescope.com/italy2020 S&T’s 2020 solar eclipse cruise offers 2 2020 Eclipse Cruise: Chile, Argentina, minutes, 7 seconds of totality off the and Antarctica coast of Argentina and much more: Nov. 27–Dec. 19, 2020 Chilean fjords and glaciers, the legendary Drake Passage, and four days amid Antarctica’s waters and icebergs. skyandtelescope.com/chile2020 Patagonian Total Solar Eclipse December 9–18, 2020 Come along with Sky & Telescope to view this celestial spectacle in the lakes region of southern Argentina. Experience breathtaking vistas of the lush landscape by day — and the southern sky’s incompa- rable stars by night. -

The Universe of Marvel: the Milky Way Galaxy

The Universe of Marvel: The Milky Way Galaxy Our galaxy is contains over a hundred billion stars. It measures 100,000 light years across and has an average depth of several thopusand light years. Earth's home, the Sol System, is 27,000 light years from the galactic center. The Milky Way is home to a myriad of races and cultures ranging from primitive tribes to interstellar empires. Unlike other galaxies in the Marvel Universe, such as Andromeda or the Greater Magellanic Cloud, no single race or culture dominates this galaxy. There are several interstellar empires in existence (Badoon, Interplaneteur Inc., Quists, Rigellians, Sagittarians, Sneepers, Stonians, Vegans), a few in decline (The Charter, The Universal Church of Truth), and some now represented only by ruins or a handful of survivors (Dionists). Getting Along With the Neighbors Earth has a peculiar place in the Milky Way. It is located near a nexus of naturally-occuring space warps and is thus relatively easy to get to. It is also home to the Human race, a race that is rapidly developing a reputation as a world to be reckoned with. It is also the source of the largest concentration of superpowered beings in the galaxy. Despite Earth's reputation and army of defenders, it remains a tempting target for would-be conquerors. In the past, Earth has been the target of attacks by such galactic neighbors as the A-Chiltarians, Alpha Centaurians, Autocrons, Fromans, Kronans, Quists, Stonians, Tribbites, Vegans, and Zn'rx. Passing as Terran Humans and humanoid races dominate the Milky Way. -

June 2017 BRAS Newsletter

June 2017 Issue Next Meeting: Monday, June 12th at 7PM at HRPO nd (2 Mondays, Highland Road Park Observatory) Presenter: Dr. Gabriela Gonzalez, spokesperson for the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, on “Einstein, Gravitational Waves and Black Holes”. What's In This Issue? President’s Message Secretary's Summary Outreach Report - FAE Event Photos Light Pollution Committee Report Recent Forum Entries 20/20 Vision Campaign Messages from the HRPO American Radio Relay League Field Day Observing Notes – Corvus –The Crow & Mythology Like this newsletter? See past issues back to 2009 at http://brastro.org/newsletters.html Newsletter of the Baton Rouge Astronomical Society June 2017 President’s Message Summer is upon us. On June 21st, at 11:24 AM CDT, summer officially begins for the Northern Hemisphere. We have a lot of outreach requests for June; the July BRAS meeting will be our annual picnic at LIGO; and one week after the August BRAS meeting is the total eclipse of the Sun. What are your plans for the summer? Will you go somewhere to see the eclipse? The band of totality runs from Georgia across the continental US to Oregon. Last month we did outreach at the Bluebonnet Swamp’s FAE Fest/20th Anniversary event. Due to a cloud cover most of the day, there was little solar viewing, but we did interact with close to 300 people, including a former member of BRAS (about 20 years ago) who expressed interest in re-joining us. The Astronomical League has awarded Comet Observing (#91) to Coy Wagoner. Congratulations Coy! In step with the April BRAS meeting’s speaker, Dr. -

AST 1A INTRODUCTION to the SOLAR SYSTEM Fall 2016 1 CH 2 Vocabulary ALL (DUE 2/23) Constellation Asterism Magnitude Scale Ap

AST 1A INTRODUCTION TO THE SOLAR SYSTEM Fall 2016 CH 2 Vocabulary ALL (DUE 2/23) constellation asterism magnitude scale apparent visual magnitude, mv flux celestial sphere scientific model north celestial pole south celestial pole horizon north point south point east point west point zenith nadir celestial equator angular distance arc minute arc second angular diameter circumpolar constellation precession rotation revolution ecliptic vernal equinox summer solstice autumnal equinox winter solstice perihelion aphelion evening star morning star zodiac horoscope pseudoscience scientific argument 1 AST 1A INTRODUCTION TO THE SOLAR SYSTEM Fall 2016 Review Questions 1-3, 10-12 (DUE 2/28) 1. Why are most modern constellations composed of faint stars or located in the southern sky? 2. How does the Greek-letter designation of a star give you clues both to its location and its brightness? 3. From your knowledge of star names and constellations, which of the following stars in each pair is the brighter? Explain your answers. a. Alpha Ursae Majoris; Epsilon Ursae Majoris b. Epsilon Scorpii; Alpha Pegasi c. Alpha Telescopii; Alpha Orionis 10. Why does the number of circumpolar constellations depend on the latitude of the observer? 11. Explain the two reasons why winter days are colder than summer days. 12. How do the seasons in Earth’s southern hemisphere differ from those in the northern hemisphere? Problems 2-4, 7 (DUE 2/28) 2. If one star is 6.3 times brighter than another star, how many magnitudes brighter is it? 3. If light from one star is 40 times brighter (has 40 times more flux) than light from another star, what is their difference in magnitude? 4. -

1455189355674.Pdf

THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN Cover by: Peter Bradley LEGAL PAGE: Every effort has been made not to make use of proprietary or copyrighted materi- al. Any mention of actual commercial products in this book does not constitute an endorsement. www.trolllord.com www.chenaultandgraypublishing.com Email:[email protected] Printed in U.S.A © 2013 Chenault & Gray Publishing, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Storyteller’s Thesaurus Trademark of Cheanult & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Chenault & Gray Publishing, Troll Lord Games logos are Trademark of Chenault & Gray Publishing. All Rights Reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS THE STORYTeller’S THESAURUS 1 FANTASY, HISTORY, AND HORROR 1 JAMES M. WARD AND ANNE K. BROWN 1 INTRODUCTION 8 WHAT MAKES THIS BOOK DIFFERENT 8 THE STORYTeller’s RESPONSIBILITY: RESEARCH 9 WHAT THIS BOOK DOES NOT CONTAIN 9 A WHISPER OF ENCOURAGEMENT 10 CHAPTER 1: CHARACTER BUILDING 11 GENDER 11 AGE 11 PHYSICAL AttRIBUTES 11 SIZE AND BODY TYPE 11 FACIAL FEATURES 12 HAIR 13 SPECIES 13 PERSONALITY 14 PHOBIAS 15 OCCUPATIONS 17 ADVENTURERS 17 CIVILIANS 18 ORGANIZATIONS 21 CHAPTER 2: CLOTHING 22 STYLES OF DRESS 22 CLOTHING PIECES 22 CLOTHING CONSTRUCTION 24 CHAPTER 3: ARCHITECTURE AND PROPERTY 25 ARCHITECTURAL STYLES AND ELEMENTS 25 BUILDING MATERIALS 26 PROPERTY TYPES 26 SPECIALTY ANATOMY 29 CHAPTER 4: FURNISHINGS 30 CHAPTER 5: EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 ADVENTurer’S GEAR 31 GENERAL EQUIPMENT AND TOOLS 31 2 THE STORYTeller’s Thesaurus KITCHEN EQUIPMENT 35 LINENS 36 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS -

Lists and Charts of Autostar Named Stars

APPENDIX A Lists and Charts of Autostar Named Stars Table A.I provides a list of named stars that are stored in the Autostar database. Following the list, there are constellation charts which show where the stars are located. The names are in alphabetical orderalong with their Latin designation (see Appendix B for complete list ofconstellations). Names in brackets 0 in the table denote a different spelling to one that is known in the list. The star's co-ordinates are set to the same as accuracy as the Autostar co-ordinates i.e. the RA or Dec 'sec' values are omitted. Autostar option: Select Item: Object --+ Star --+ Named 215 216 Appendix A Table A.1. Autostar Named Star List RA Dec Named Star Fig. Ref. latin Designation Hr Min Deg Min Mag Acamar A5 Theta Eridanus 2 58 .2 - 40 18 3.2 Achernar A5 Alpha Eridanus 1 37.6 - 57 14 0.4 Acrux A4 Alpha Crucis 12 26.5 - 63 05 1.3 Adara A2 EpsilonCanis Majoris 6 58.6 - 28 58 1.5 Albireo A4 BetaCygni 19 30.6 ++27 57 3.0 Alcor Al0 80 Ursae Majoris 13 25.2 + 54 59 4.0 Alcyone A9 EtaTauri 3 47.4 + 24 06 2.8 Aldebaran A9 Alpha Tauri 4 35.8 + 16 30 0.8 Alderamin A3 Alpha Cephei 21 18.5 + 62 35 2.4 Algenib A7 Gamma Pegasi 0 13.2 + 15 11 2.8 Algieba (Algeiba) A6 Gamma leonis 10 19.9 + 19 50 2.6 Algol A8 Beta Persei 3 8.1 + 40 57 2.1 Alhena A5 Gamma Geminorum 6 37.6 + 16 23 1.9 Alioth Al0 EpsilonUrsae Majoris 12 54.0 + 55 57 1.7 Alkaid Al0 Eta Ursae Majoris 13 47.5 + 49 18 1.8 Almaak (Almach) Al Gamma Andromedae 2 3.8 + 42 19 2.2 Alnair A6 Alpha Gruis 22 8.2 - 46 57 1.7 Alnath (Elnath) A9 BetaTauri 5 26.2 -

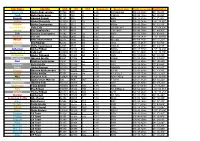

Star Name Identity SAO HD FK5 Magnitude Spectral Class Right Ascension Declination Alpheratz Alpha Andromedae 73765 358 1 2,06 B

Star Name Identity SAO HD FK5 Magnitude Spectral class Right ascension Declination Alpheratz Alpha Andromedae 73765 358 1 2,06 B8IVpMnHg 00h 08,388m 29° 05,433' Caph Beta Cassiopeiae 21133 432 2 2,27 F2III-IV 00h 09,178m 59° 08,983' Algenib Gamma Pegasi 91781 886 7 2,83 B2IV 00h 13,237m 15° 11,017' Ankaa Alpha Phoenicis 215093 2261 12 2,39 K0III 00h 26,283m - 42° 18,367' Schedar Alpha Cassiopeiae 21609 3712 21 2,23 K0IIIa 00h 40,508m 56° 32,233' Deneb Kaitos Beta Ceti 147420 4128 22 2,04 G9.5IIICH-1 00h 43,590m - 17° 59,200' Achird Eta Cassiopeiae 21732 4614 3,44 F9V+dM0 00h 49,100m 57° 48,950' Tsih Gamma Cassiopeiae 11482 5394 32 2,47 B0IVe 00h 56,708m 60° 43,000' Haratan Eta ceti 147632 6805 40 3,45 K1 01h 08,583m - 10° 10,933' Mirach Beta Andromedae 54471 6860 42 2,06 M0+IIIa 01h 09,732m 35° 37,233' Alpherg Eta Piscium 92484 9270 50 3,62 G8III 01h 13,483m 15° 20,750' Rukbah Delta Cassiopeiae 22268 8538 48 2,66 A5III-IV 01h 25,817m 60° 14,117' Achernar Alpha Eridani 232481 10144 54 0,46 B3Vpe 01h 37,715m - 57° 14,200' Baten Kaitos Zeta Ceti 148059 11353 62 3,74 K0IIIBa0.1 01h 51,460m - 10° 20,100' Mothallah Alpha Trianguli 74996 11443 64 3,41 F6IV 01h 53,082m 29° 34,733' Mesarthim Gamma Arietis 92681 11502 3,88 A1pSi 01h 53,530m 19° 17,617' Navi Epsilon Cassiopeiae 12031 11415 63 3,38 B3III 01h 54,395m 63° 40,200' Sheratan Beta Arietis 75012 11636 66 2,64 A5V 01h 54,640m 20° 48,483' Risha Alpha Piscium 110291 12447 3,79 A0pSiSr 02h 02,047m 02° 45,817' Almach Gamma Andromedae 37734 12533 73 2,26 K3-IIb 02h 03,900m 42° 19,783' Hamal Alpha -

Brightest Stars : Discovering the Universe Through the Sky's Most Brilliant Stars / Fred Schaaf

ffirs.qxd 3/5/08 6:26 AM Page i THE BRIGHTEST STARS DISCOVERING THE UNIVERSE THROUGH THE SKY’S MOST BRILLIANT STARS Fred Schaaf John Wiley & Sons, Inc. flast.qxd 3/5/08 6:28 AM Page vi ffirs.qxd 3/5/08 6:26 AM Page i THE BRIGHTEST STARS DISCOVERING THE UNIVERSE THROUGH THE SKY’S MOST BRILLIANT STARS Fred Schaaf John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.qxd 3/5/08 6:26 AM Page ii This book is dedicated to my wife, Mamie, who has been the Sirius of my life. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2008 by Fred Schaaf. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada Illustration credits appear on page 272. Design and composition by Navta Associates, Inc. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copy- right.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. -

The COLOUR of CREATION Observing and Astrophotography Targets “At a Glance” Guide

The COLOUR of CREATION observing and astrophotography targets “at a glance” guide. (Naked eye, binoculars, small and “monster” scopes) Dear fellow amateur astronomer. Please note - this is a work in progress – compiled from several sources - and undoubtedly WILL contain inaccuracies. It would therefor be HIGHLY appreciated if readers would be so kind as to forward ANY corrections and/ or additions (as the document is still obviously incomplete) to: [email protected]. The document will be updated/ revised/ expanded* on a regular basis, replacing the existing document on the ASSA Pretoria website, as well as on the website: coloursofcreation.co.za . This is by no means intended to be a complete nor an exhaustive listing, but rather an “at a glance guide” (2nd column), that will hopefully assist in choosing or eliminating certain objects in a specific constellation for further research, to determine suitability for observation or astrophotography. There is NO copy right - download at will. Warm regards. JohanM. *Edition 1: June 2016 (“Pre-Karoo Star Party version”). “To me, one of the wonders and lures of astronomy is observing a galaxy… realizing you are detecting ancient photons, emitted by billions of stars, reduced to a magnitude below naked eye detection…lying at a distance beyond comprehension...” ASSA 100. (Auke Slotegraaf). Messier objects. Apparent size: degrees, arc minutes, arc seconds. Interesting info. AKA’s. Emphasis, correction. Coordinates, location. Stars, star groups, etc. Variable stars. Double stars. (Only a small number included. “Colourful Ds. descriptions” taken from the book by Sissy Haas). Carbon star. C Asterisma. (Including many “Streicher” objects, taken from Asterism.