Pushback: Democracies Delegitimising a Free Press the Beginnings of Tampering with an Open Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf Dokument

Udskriftsdato: 2. oktober 2021 2017/1 BTB 91 (Gældende) Betænkning over Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om en uvildig undersøgelse af udlændinge og integrationsministerens håndtering af adskilt indkvartering af mindreårige gifte eller samlevende asylansøgere Ministerium: Folketinget Betænkning afgivet af Udvalget for Forretningsordenen den 23. maj 2018 Betænkning over Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om en uvildig undersøgelse af udlændinge- og integrationsministerens håndtering af adskilt indkvartering af mindreårige gifte eller samlevende asylansøgere [af Mattias Tesfaye (S), Nikolaj Villumsen (EL), Josephine Fock (ALT), Sofie Carsten Nielsen (RV) og Holger K. Nielsen (SF)] 1. Udvalgsarbejdet Beslutningsforslaget blev fremsat den 14. marts 2018 og var til 1. behandling den 26. april 2018. Be- slutningsforslaget blev efter 1. behandling henvist til behandling i Udvalget for Forretningsordenen. Møder Udvalget har behandlet beslutningsforslaget i 2 møder. 2. Indstillinger og politiske bemærkninger Et flertal i udvalget (DF, V, LA og KF) indstiller beslutningsforslaget til forkastelse. Flertallet konstaterer, at sagen om udlændinge- og integrationsministerens håndtering af adskilt ind- kvartering af mindreårige gifte eller samlevende asylansøgere er blevet diskuteret i mange, lange samråd, og at sagen derfor er belyst. Flertallet konstaterer samtidig, at ministeren flere gange har redegjort for forløbet. Det er sket både skriftligt og mundtligt. Flertallet konstaterer også, at den kritik, som Folketingets Ombudsmand rettede mod forløbet i 2017, er en kritik, som udlændinge- og integrationsministeren har taget til efterretning. Det gælder både kritikken af selve ordlyden i pressemeddelelsen og kritikken af, at pressemeddelelsen medførte en risiko for forkerte afgørelser. Flertallet mener, at det afgørende har været, at der blev lagt en så restriktiv linje som muligt. For flertallet ønsker at beskytte pigerne bedst muligt, og flertallet ønsker at bekæmpe skikken med barnebru- de. -

Kandidattest Fv15

KANDIDATTEST FV15 SPØRGSMÅL HELT UENIG DELVIST UENIG HVERKEN/ELLER DELVIST ENIG HELT ENIG Efter folkeskolereformen får eleverne for lange skoledage CCCC IIIIII KKKKKKKKKK OOO AAA B F O VVVVVV AAAAA BBB C FFFFF O VV O B C I OOOO V ØØ ÅÅ ØØØØØØØ Å Afgiften på cigaretter skal sættes op AAAAA B CC F KKK O V ØØØØ C IIIIII K OOOOO VV F I O VVVVV A B C KK O V ØØ Å AA BBB CC FFFF KKKK O ØØØ ÅÅ Et besøg hos den praktiserende læge skal koste eksempelvis 100 kr. AAAAAAA CCCC FFFFFF KKKKKK OOOOOOOO V ØØØØØØØØØ ÅÅ A BB C KKK OO VVVV C V B II K VVV Å BB IIIII Mere af ældreplejen skal udliciteres til private virksomheder AAAA BB FFFFFF KKK OOO ØØØØØØØØØ ÅÅ AAAA BB KKK OOOO C KKK OO Å B CCCCC I K O VVVVVVVV IIIIII V Man skal hurtigere kunne genoptjene retten til dagpenge AAAAA B FFFFFF KKKKKK OOOOOOO BBB CCCC IIIIIII K VV CC O VVV AA B K O VV A KK OO VV Å ØØØØØØØØØ ÅÅ Virksomheder skal kunne drages til ansvar for, om deres udenlandske underleverandører i Danmark overholder danske regler om løn, moms og skat AAAAA BBB CC FFFFFF KKK B CC IIIIIII KK O VVV A C KKK O VVVV C O AA B KK O VV Å OOOOOO ØØØØØØØØØ ÅÅ Vækst i den offentlige sektor er vigtigere end skattelettelser B CCCCCC IIIIIII O VVVVVVVVV BB KK OO KKKK OO ÅÅ AAAAAA BB KKK OO Å AA FFFFFF K OOO ØØØØØØØØØ Investeringer i kollektiv trafik skal prioriteres højere end investeringer til fordel for privatbilisme III KK OOOOO VVV Ø CCC IIII OO VVVV AAA BB CC KKKK O V AAA BB C FFF KKKK O V Ø Å AA FFF O ØØØØØØØ ÅÅ Straffen for grov vold og voldtægt skal skærpes CCCC IIIIIII KKKK OOOOOOOOOO BBB F ØØØ A B -

Opskriften På Succes Stort Tema Om Det Nye Politiske Landkort

UDGAVE NR. 5 EFTERÅR 2016 Uffe og Anders Opskriften på succes Stort tema om det nye politiske landkort MAGTDUO: Metal-bossen PORTRÆT: Kom tæt på SKIPPER: Enhedslistens & DI-direktøren Dansk Flygtningehjælps revolutionære kontrolfreak topchef www.mercuriurval.dk Ledere i bevægelse Ledelse i balance Offentlig ledelse + 150 85 250 toplederansættelser konsulenter over ledervurderinger og i den offentlige sektor hele landet udviklingsforløb på over de sidste tre år alle niveauer hvert år Kontakt os på [email protected] eller ring til os på 3945 6500 Fordi mennesker betyder alt EFTERÅR 2016 INDHOLD FORDOMME Levebrød, topstyring og superkræfter 8 PORTRÆT Skipper: Enhedslistens nye profil 12 NYBRUD Klassens nye drenge Anders Samuelsen og Uffe Elbæk giver opskriften på at lave et nyt parti. 16 PARTIER Nyt politisk kompas Hvordan ser den politiske skala ud i dag? 22 PORTRÆT CEO for flygningehjælpen A/S Kom tæt på to-meter-manden Andreas Kamm, som har vendt Dansk Flygtningehjælp fra krise til succes. 28 16 CIVILSAMFUND Danskerne vil hellere give gaver end arbejde frivilligt 34 TOPDUO Spydspidserne 52 Metal-bossen Claus Jensen og DI-direktøren Karsten Dybvad udgør et umage, men magtfuldt par. 40 INDERKREDS Topforhandlerne Mød efterårets centrale politikere. 44 INTERVIEW Karsten Lauritzen: Danmark efter Brexit 52 BAGGRUND Den blinde mand og 12 kampen mod kommunerne 58 KLUMME Klumme: Jens Christian Grøndahl 65 3 ∫magasin Efterår 2016 © �∫magasin er udgivet af netavisen Altinget ANSVARSHAVENDE CHEFREDAKTØR Rasmus Nielsen MAGASINREDAKTØR Mads Bang REDAKTION Anders Jerking Erik Holstein Morten Øyen Jensen Klaus Ulrik Mortensen Kasper Frandsen Mads Bang Hjalte Kragesteen Sine Riis Lund Kim Rosenkilde Rikke Albrechtsen Anne Justesen Frederik Tillitz Erik Bjørn Møller Toke Gade Crone Kristiansen Søren Elkrog Friis Emma Qvirin Holst Carsten Terp Rasmus Løppenthin Amalie Bjerre Christensen Tyson W. -

Bilag 1: Kodning

Bilag 1: Kodning Artikel Forfatter Medie Dato Gruppe Udtaler sig Professorer: Lavere kontanthjælp vil sende unge i uddannelse Casper Dall Information 07.08.12 Incitament Lars Barfoed (K) Morten Skjoldager, Kenneth Lund, Oliver Bærentsen, Flere unge ryger på kontanthjælp Jesper Hvass Politiken 18.01.13 pastoral Mette Frederiksen (S) Minister vil skrue bissen på over for Henrik unge på kontanthjælp Dannemand Berlingske 16.01.12 pastoral Mette Frederiksen (S) Morten Skjoldager, Kenneth Lund, Regeringen: Flere unge skal fra Oliver Bærentsen, Nadeem Faroq (R), kontanthjælp til SU Jesper Hvass Politiken 18.01.13 X Jesper Jespersen (SF) Annette Bonde, Magrethe Vestager (R), Unge skal glemme alt om kontanthjælp Peter Burhøi Berlingske 25.02.13 X Mette Frederiksen (S) Mie Raatz, Interview: Det er blevet et livsvilkår, at Tanja Astrup man er på kontanthjælp Parker Politiken 15.12.13 Pastoral Mette Frederiksen (S) Chris Kjær Jessen, Ulla Tørnæs (V), Unge får råd til mere på kontanthjælp Carl Emil Arnfred Berlingske 30.08.12 X Mette Frederiksen (S) Tusindvis af unge barberes i Sanne Rubinke (SF), kontanthjælp Jesper Vangkilde Politiken 24.02.13 X Sofie Carlsen Nielsen (R) mfl. Chris Kjær Jessen, Jesper Thobo- Ulla Tørnæs (V), Vil halvere dagpenge for unge Carlsen BT 16.02.12 Incitament Leif Lahn Jensen (S) Unge på kontanthjælp: Danskerne vil Mette Frederiksen (S) tvinge unge i arbejdstøjet Ritzau Information 18.02.12 X Bent Bøgsted (DF) mfl. Minister: Usundt at tjene på Carl Emil Arnfred, Berlingske 30.08.12 Disciplin, Nadeem Faroq (R), kontanthjælp Chris Kjær Jessen incitament Ulla Tørnæs (V) mfl. Rekordmange uuddannede unge på Rasmus Bøttcher Ulla Tørnæs (V), kontanthjælp Christensen Politiken 21.12.11 X Mai Henriksen (K) mfl. -

EUI RSCAS Working Paper 2020

RSCAS 2020/88 Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Integrating Diversity in the European Union (InDivEU) The Politics of Differentiated Integration: What do Governments Want? Country Report - Denmark Viktor Emil Sand Madsen European University Institute Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Integrating Diversity in the European Union (InDivEU) The Politics of Differentiated Integration: What do Governments Want? Country Report - Denmark Viktor Emil Sand Madsen EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2020/88 Terms of access and reuse for this work are governed by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC- BY 4.0) International license. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper series and number, the year and the publisher. ISSN 1028-3625 © Viktor Emil Sand Madsen, 2020 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC-BY 4.0) International license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Published in December 2020 by the European University Institute. Badia Fiesolana, via dei Roccettini 9 I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual author(s) and not those of the European University Institute. This publication is available in Open Access in Cadmus, the EUI Research Repository: https://cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, created in 1992 and currently directed by Professor Brigid Laffan, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research on the major issues facing the process of European integration, European societies and Europe’s place in 21st century global politics. -

Røde Kvinder Mod Blå Mænd

BERLINGSKE / 1.SEKTION / TIRSDAG 11.09.2012 08. / NATIONALT / REDIGERET AF METTE VOSGERAU . LAYOUT: FINN MIKALSKI Køn. Med en kvinde som sandsynlig ny SF-formand vil rød blok have fire kvindelige partiledere. Omvendt er der nu i blå blok lutter mænd i spidsen. Spørgsmålet er, hvem der har størst fordel af kønssammensætningen ved næste valg? LARS LØKKE RASMUSSEN Røde kvinder HELLE THORNING-SCHMIDT mod blå mænd Af Morten Henriksen // [email protected] har nogle meget »mandlige« holdninger, og Peter Burhøi // [email protected] om man vil, om den økonomiske politik. Og man har også en spredning i alder. De fire Næste valg kan blive ikke bare partiernes mandlige partiledere minder meget om hin- kamp, men også kønnenes kamp. Med anden – fire bankfuldmægtige,« siger han. udsigten til, at SFs medlemmer vælger enten Hvis nogle fra blå blok skulle føle sig fri- Astrid Krag eller en anden kvindelig kandi- stet til at slå på, at mandlige partiledere er det dat som ny partiformand, kan samtlige par- mere sikre, mere gennemprøvede valg, kan tier i rød blok have en kvindelig partileder det give bagslag, vurderer Anette Borchorst. om nogle måneder. Og med den kommende »Virkeligheden dementerer det jo også: weekends landsmøde i Dansk Folkeparti, Villy Søvndal har eksempelvis haft større hvor Kristian Thulesen Dahl overtager for- problemer end Helle Thorning,« siger hun. ANDERS SAMUELSEN mandsposten efter Pia Kjærsgaard, vil blå Blå blok har da heller ikke tænkt sig at MARGRETHE VESTAGER blok omvendt mønstre fire mandlige parti- spille »kønskortet« i den kommende valg- formænd. kamp. »Billedet med fire kvinder over for fire »Det mener jeg slet ikke er en diskussion. -

High-Level Statement1

HIGH-LEVEL STATEMENT1 We made promises which we intend to keep. We promised that women and girls would be at the center of many of the Sustainable Development Goals which the world came together to agree in 2016. America’s Global Gag Rule breaks that promise as it has a chilling effect on health services for the world’s most vulnerable women and girls. It will imperil millions of women and girls’ lives by increasing unintended pregnancies and unsafe abortions. It will also reverse decades of progress on reproductive, maternal and child health by putting critical health and family planning services and supplies out of reach for those who most need them. There are currently 225 million women in developing countries who want to avoid pregnancy but are not using modern contraception. Maternal mortality is the second‐leading cause of death for girls aged 15 to 19 years old, and the burden of unsafe abortion also falls overwhelmingly on the poorest. The evidence shows that access to contraception is transformative for girls, women and their families and communities. It is linked to greater gender equality, educational attainment and economic development. Health providers around the world face a painful choice between losing their US funding and losing the freedom to offer a full range of reproductive health services. We’ve been here before. Since its inception in 1984, the Global Gag Rule has been put into place at the start of every Republican administration and promptly rescinded under each Democratic administration. It’s time to take politics out of gender rights. -

Betænkning\ 1\.\

Folketinget 2007-08 (2. samling) Til beslutningsforslag nr. B 26 Betænkning afgivet af Trafikudvalget den 0. maj 2008 1. udkast Betænkning over Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om genforhandling af aftalen af 29. juni 2007 mellem Kongeriget Danmark og Forbundsrepublikken Tyskland vedrørende den faste forbindelse over Femern Bælt [af Kim Christiansen (DF) m.fl.] 1. Udvalgsarbejdet Beslutningsforslaget blev fremsat den 14. december 2007 og var til 1. behandling den 31. januar 2008. Beslutningsforslaget blev efter 1. behandling henvist til behandling i Trafikudvalget. Møder Udvalget har behandlet beslutningsforslaget i <> møder. Spørgsmål Udvalget har stillet 3 spørgsmål til transportministeren til skriftlig besvarelse, som denne har be- svaret. 2. Indstillinger og politiske bemærkninger <> Ny Alliance, Inuit Ataqatigiit, Siumut, Tjóðveldisflokkurin og Sambandsflokkurin var på tids- punktet for betænkningens afgivelse ikke repræsenteret med medlemmer i udvalget og havde der- med ikke adgang til at komme med indstillinger eller politiske udtalelser i betænkningen. En oversigt over Folketingets sammensætning er optrykt i betænkningen.[ Der gøres opmærksom på, at et flertal eller et mindretal i udvalget ikke altid vil afspejle et flertal/mindretal ved afstemning i Folketingssalen.] Jens Vibjerg (V) Flemming Damgaard Larsen (V) fmd. Kristian Pihl Lorentzen (V) Hans Christian Schmidt (V) Karsten Nonbo (V) Kim Christiansen (DF) Pia Adelsteen (DF) Henriette Kjær (KF) nfmd. Lars Barfoed (KF) Magnus Heunicke (S) Jens Christian Lund (S) Poul Andersen -

Betænkning Over Forslag Til Lov Om Ændring Af Værnepligtsloven (Fritagelse for Værnepligtstjeneste for Visse Personer, Der Er Blevet Udskrevet Til Tjeneste Før 2010)

Udskriftsdato: 27. september 2021 2018/1 BTL 4 (Gældende) Betænkning over Forslag til lov om ændring af værnepligtsloven (Fritagelse for værnepligtstjeneste for visse personer, der er blevet udskrevet til tjeneste før 2010) Ministerium: Folketinget Betænkning afgivet af Forsvarsudvalget den 22. november 2018 Betænkning over Forslag til lov om ændring af værnepligtsloven (Fritagelse for værnepligtstjeneste for visse personer, der er blevet udskrevet til tjeneste før 2010) [af forsvarsministeren (Claus Hjort Frederiksen)] 1. Indstilling Udvalget indstiller lovforslaget til vedtagelse uændret. Nunatta Qitornai, Tjóðveldi og Javnaðarflokkurin havde ved betænkningsafgivelsen ikke medlemmer i udvalget og dermed ikke adgang til at komme med indstillinger eller politiske bemærkninger i betænknin- gen. En oversigt over Folketingets sammensætning er optrykt i betænkningen. 2. Politiske bemærkninger Enhedslisten og Inuit Ataqatigiit Enhedslistens og Inuit Ataqatigiits medlemmer af udvalget bemærker, at der er en principiel udfordring i, at regeringen fremsætter ændringslovforslag til en lov, der gælder i hele rigsfællesskabet. Det fremgår i høringsoversigten, at regeringen har til hensigt at udarbejde en kongelig anordning for Grønland og Færøerne senere. Når dette sker, vil Inatsisartut komme med en udtalelse, jf. selvstyreloven, men det er uskøn proces, når der er tale om en lov, der omhandler hele rigsfællesskabet, som ændres i forskellige tempi, afhængigt af hvor i rigsfællesskabet man som borger befinder sig. 3. Udvalgsarbejdet Lovforslaget blev fremsat den 3. oktober 2018 og var til 1. behandling den 11. oktober 2018. Lovfor- slaget blev efter 1. behandling henvist til behandling i Forsvarsudvalget. Oversigt over lovforslagets sagsforløb og dokumenter Lovforslaget og dokumenterne i forbindelse med udvalgsbehandlingen kan læses under lovforslaget på Folketingets hjemmeside www.ft.dk. -

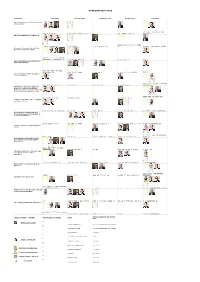

Det Offentlige Danmark 2018 © Digitaliseringsstyrelsen, 2018

Det offentlige Danmark 2018 © Digitaliseringsstyrelsen, 2018 Udgiver: Finansministeriet Redaktion: Digitaliseringsstyrelsen Opsætning og layout: Rosendahls a/s ISBN 978-87-93073-23-4 ISSN 2446-4589 Det offentlige Danmark 2018 Oversigt over indretningen af den offentlige sektor Om publikationen Den første statshåndbog i Danmark udkom på tysk i Oversigt over de enkelte regeringer siden 1848 1734. Fra 1801 udkom en dansk udgave med vekslende Frem til seneste grundlovsændring i 1953 er udelukkende udgivere. Fra 1918 til 1926 blev den udgivet af Kabinets- regeringscheferne nævnt. Fra 1953 er alle ministre nævnt sekretariatet og Indenrigsministeriet og derefter af Kabi- med partibetegnelser. netssekretariatet og Statsministeriet. Udgivelsen Hof & Stat udkom sidste gang i 2013 i fuld version. Det er siden besluttet, at der etableres en oversigt over indretningen Person- og realregister af den offentlige sektor ved nærværende publikation, Der er ikke udarbejdet et person- og realregister til som udkom første gang i 2017. Det offentlige Danmark denne publikation. Ønsker man at fremfnde en bestem indeholder således en opgørelse over centrale instituti- person eller institution, henvises der til søgefunktionen oner i den offentlige sektor i Danmark, samt hvem der (Ctrl + f). leder disse. Hofdelen af den tidligere Hof- og Statskalen- der varetages af Kabinetssekretariatet, som stiller infor- mationer om Kongehuset til rådighed på Kongehusets Redaktionen hjemmeside. Indholdet til publikationen er indsamlet i første halvår 2018. Myndighederne er blevet -

Day by Day Summary of the Election Campaign

Day by Day Summary of the Election Campaign Friday, 26 August It was Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen’s plan to introduce a bonus to people purchasing a house. This bonus has been criticized for artificially inflating house prices and therefore for being a bad way to instigate growth. On Saturday 20 August the Social Democrats (S) somehow learned about the plan and decided to launch it themselves, despite Helle Thorning-Schmidt having said on Friday that she did not want to introduce measures to stimulate the housing market. This led to a chaotic Saturday where Løkke Rasmussen and the Liberal Party (V) tried to do damage control. Quickly the Danish People’s Party (DF) declared their opposition to the plan due to a lot of their voters not being house owners. Liberal Alliance (LA) is as a general rule opposed to state subsidies so they were opposed as well leaving V and the Conservative Party (K) alone with the plan on the blue wing. On the red wing the situation was similar. S and the Socialist People’s Party (SF) agreed on the idea while the Unity List (EL) represents the left wing and therefore does not believe in the state funding those with the means to buy a house – plus a lot of their voters rent their homes. The Social Liberal Party (R) is opposed with the argument that the plan is a shortsighted one which will probably not do much for the economy anyway. Thus S-SF and VK were alone and they did not want to cooperate to get a majority for the plan. -

Betænkning Forslag Til Lov Om Ændring Af Lov Om

Til lovforslag nr. L 136 Folketinget 2015-16 Betænkning afgivet af Social- og Indenrigsudvalget den 28. april 2016 Betænkning over Forslag til lov om ændring af lov om Offentlig Digital Post (Bemyndigelse til at fastsætte regler om størrelse på filer m.v.) [af finansministeren (Claus Hjort Frederiksen)] 1. Udvalgsarbejdet 2. Indstilling Lovforslaget blev fremsat den 25. februar 2016 og var til Udvalget indstiller lovforslaget til vedtagelse uændret. 1. behandling den 15. marts 2016. Lovforslaget blev efter 1. Inuit Ataqatigiit, Siumut, Tjóðveldi og Javnaðarflokkurin behandling henvist til behandling i Social- og Indenrigsud- var på tidspunktet for betænkningens afgivelse ikke repræ- valget. senteret med medlemmer i udvalget og havde dermed ikke adgang til at komme med indstillinger eller politiske udtalel- Møder ser i betænkningen. Udvalget har behandlet lovforslaget i 2 møder. En oversigt over Folketingets sammensætning er optrykt i betænkningen. Høring Et udkast til lovforslaget har inden fremsættelsen været sendt i høring. Den 15. marts 2016 sendte finansministeren de indkomne høringssvar og et notat herom til udvalget. Karin Nødgaard (DF) nfmd. Susanne Eilersen (DF) Karina Adsbøl (DF) Jan Rytkjær Callesen (DF) Dorthe Ullemose (DF) Karina Due (DF) Jakob Engel-Schmidt (V) Carl Holst (V) Jane Heitmann (V) Hans Andersen (V) Thomas Danielsen (V) Anni Matthiesen (V) Henrik Dahl (LA) Laura Lindahl (LA) Anders Johansson (KF) Karen J. Klint (S) Malte Larsen (S) Orla Hav (S) Pernille Rosenkrantz-Theil (S) fmd. Troels Ravn (S) Trine Bramsen (S) Yildiz Akdogan (S) Rune Lund (EL) Pernille Skipper (EL) Torsten Gejl (ALT) Marianne Jelved (RV) Andreas Steenberg (RV) Trine Torp (SF) Karsten Hønge (SF) Inuit Ataqatigiit, Siumut, Tjóðveldi og Javnaðarflokkurin havde ikke medlemmer i udvalget.