Analysis of the Petroleum Systems of the Lusitanian Basin (Western Iberian Margin)—A Tool for Deep Offshore Exploration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. the Western Iberia Margin: a Geophysical and Geological Overview1

Whitmarsh, R.B., Sawyer, D.S., Klaus, A., and Masson, D.G. (Eds.), 1996 Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Program, Scientific Results, Vol. 149 1. THE WESTERN IBERIA MARGIN: A GEOPHYSICAL AND GEOLOGICAL OVERVIEW1 L.M. Pinheiro,2 R.C.L. Wilson,3 R. Pena dos Reis,4 R.B. Whitmarsh,5 A. Ribeiro6 ABSTRACT This paper presents a general overview of the geology and geophysics of western Iberia, and in particular of the western Portuguese Margin. The links between the onshore and offshore geology and geophysics are especially emphasized. The west Iberia Margin is an example of a nonvolcanic rifted margin. The Variscan basement exposed on land in Iberia exhibits strike- slip faults and other structural trends, which had an important effect on the development, in time and space, of subsequent rift- ing of the continental margin and even perhaps influences the present-day offshore seismicity. The margin has had a long tec- tonic and magmatic history from the Late Triassic until the present day. Rifting first began in the Late Triassic; after about 70 Ma, continental separation began in the Tagus Abyssal Plain. Continental breakup then appears to have progressively migrated northwards, eventually reaching the Galicia Bank segment of the margin about 112 Ma. Although there is onshore evidence of magmatism throughout the period from the Late Triassic until 130 Ma and even later, this was sporadic and of insignificant vol- ume. Important onshore rift basins were formed during this period. Offshore, the record is complex and fragmentary. An ocean/ continent transition, over 150 km wide, lies beyond the shelf edge and is marked on its western side by a peridotite ridge and thin oceanic crust characterized by seafloor spreading anomalies. -

Call for Bids NL13-02, Area “C” - Carson Basin, Parcels 1 to 4

Petroleum Exploration Opportunities in the Carson Basin, Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Area; Call for Bids NL13-02, Area “C” - Carson Basin, Parcels 1 to 4. Government of Newfoundland Department of Natural Resources 1200 m WB 4 km NW SE By Dr. Michael Enachescu, P Geoph., P Geo. November 2013 Call for Bids NL13-02 Carson Basin Dr. Michael Enachescu Foreword This report has been prepared on behalf of the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Natural Resources (NL-DNR) to provide information on land parcels offered in the Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Offshore Petroleum Board’s (C-NLOPB) 2013 Call for Bids NL13-02. This year the C-NLOPB has issued three separate Calls for Bids, including: 1. Call for Bids NL13-01 (Flemish Pass Basin) consisting of one parcel, 2. Call for Bids NL13-02 (Carson Basin) consisting of four parcels, and 3. Call for Bids NL13-03 (Western Newfoundland) consisting of four parcels. These nine parcels on offer comprise a total of 2,409,020 hectares (5,952,818 acres) distributed in four regions of the NL Offshore area situated in the Flemish Pass, Carson, Anticosti and Magdalen basins (http://www.cnlopb.nl.ca/news/nr20130516.shtml). Call for Bids NL13-02. This report focuses on Call for Bids NL13-02 Area “C” - Carson Basin that includes four large parcels with a total area of 1,138,399 hectares (2,813,034 acres) (http://www.cnlopb.nl.ca/pdfs/nl1302.pdf). The parcels lay in shallow to deep water of the basin, east of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland and south of the Flemish Cap bathymetric features. -

Beyond Time and Space—The Aspiring Jurassic Geopark of Figueira Da Foz

geosciences Article Beyond Time and Space—The Aspiring Jurassic Geopark of Figueira da Foz Paulo Trincão 1,2,3,*, Estefânia Lopes 4, Jorge de Carvalho 1,3, Sebastião Ataíde 1 and Margarida Perrolas 1 1 City Council of Figueira da Foz, 3084-501 Figueira da Foz, Portugal; [email protected] (J.d.C.); [email protected] (S.A.); margarida.perrolas@cm-figfoz.pt (M.P.) 2 Exploratório Centro Ciência Viva de Coimbra, 3040-255 Coimbra, Portugal 3 Geoscience Center, University of Coimbra, 3030-790 Coimbra, Portugal 4 Institute of Earth Sciences—Geology Centre, University of Porto, 4169-007 Porto, Portugal; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-239-703-897 Received: 1 April 2018; Accepted: 15 May 2018; Published: 24 May 2018 Abstract: Figueira da Foz municipality has a very important geoheritage significance and the local authorities, the population and the academics recognize it. Even though it is a small-scale coast, unique geological and geomorphological features are found. It is well-known due to its international stratigraphic relevance given by the establishment of two stratotypes. The rocks of the region are well exposed along the shore, the archaeological patrimony, the cultural heritage and the biodiversity complete the region with high quality, and provide a global classroom. It is a catalogue of scientific, touristic and educational values that is being used for a long time. Because of all this became officially by UNESCO an Aspiring Jurassic Geopark of Figueira da Foz in 2018. Keywords: Aspiring Geopark; Figueira da Foz; Jurassic; culture; Mezo-Cenozoic; GSSP; ASSP 1. -

Petroleum Systems of the Central Atlantic Margins, from Outcrop and Subsurface Data

Petroleum Systems of the Central Atlantic Margins, from Outcrop and Subsurface Data Wach, Grant Pena dos Reis, Rui Dalhousie University Centro de Geociências, Faculdade de Ciências e 1355 Oxford Street Tecnologia da Universidade de Coimbra Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, B3H 4R2 Lg Marquês de Pombal e-mail: [email protected] 3000-272 Coimbra, Portugal Pimentel, Nuno e-mail: [email protected] Centro de Geologia, Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade Lisboa Campo Grande C-6 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Coastal exposures of Mesozoic sediments in the tional environments from terrigenous and non-marine, Wessex basin and Channel subbasin (southern UK), shallow siliciclastic and carbonate sediments, through and the Lusitanian basin (Portugal) provide keys to the to deep marine sediments, and clarify key stratigraphic petroleum systems being exploited for oil and gas off- surfacesGCSSEPM representing conformable and non-conform- shore Atlantic Canada. These coastal areas have able surfaces. Validation of these analog sections and striking similarities to the Canadian offshore region surfaces can help predict downdip, updip, and lateral and provide insight to controls and characteristics of potential of the petroleum systems, especially source the reservoirs. Outcrops demonstrate a range of deposi- rock and reservoir. Introduction 2014 Outcrops from analogous outcrop sections along The Wessex and Channel basins lie on Paleozoic the UK and European margins may provide new play basement deformed during the Variscan Orogeny, opportunities when the petroleum systems of the Cen- which culminated during the late Carboniferous. In tral Atlantic margin are explored and developed early Mesozoic, north-south extension created a series (Fig. -

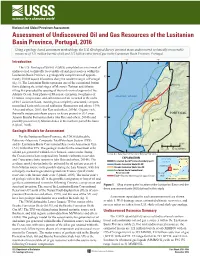

Assessment of Undiscovered Oil and Gas Resources of the Lusitanian Basin Province, Portugal, 2016 Using a Geology-Based Assessment Methodology, the U.S

National and Global Petroleum Assessment Assessment of Undiscovered Oil and Gas Resources of the Lusitanian Basin Province, Portugal, 2016 Using a geology-based assessment methodology, the U.S. Geological Survey assessed mean undiscovered, technically recoverable resources of 121 million barrels of oil and 212 billion cubic feet of gas in the Lusitanian Basin Province, Portugal. Introduction –10° –9° The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) completed an assessment of undiscovered, technically recoverable oil and gas resources within the Lusitanian Basin Province, a geologically complex area of approxi- 40° mately 20,000 square kilometers along the western margin of Portugal (fig. 1). The Lusitanian Basin represents one of the extensional basins Coimbra formed during the initial stages of Mesozoic Tethyan and Atlantic rifting that preceded the opening of the north-central segment of the T Atlantic Ocean. Four phases of Mesozoic extension, two phases of UL FA ATLANTIC OCEAN RÉ Cenozoic compression, and salt movement are recorded in the rocks NAZA of the Lusitanian Basin, resulting in a complexly structured, compart- mentalized basin with several subbasins (Rasmussen and others, 1998; Alves and others, 2003; dos Reis and others, 2014a). Organic-rich, thermally mature petroleum source rocks are present in (1) Lower PORTUGAL Jurassic Brenha Formation shales (dos Reis and others, 2014b) and 39° Santarém possibly present in (2) Silurian shales in the northern part of the basin (Uphoff, 2005). Geologic Models for Assessment LISBON For the Lusitanian Basin Province, the USGS defined the Paleozoic–Mesozoic Composite Total Petroleum System (TPS) 0 25 50 MILES and the Lusitanian Basin Conventional Reservoirs Assessment Unit Setúbal (AU) within this TPS. -

On the Tectonic Origin of Iberian Topography

On the tectonic origin of Iberian topography A.M. Casas-Sainz a,?, G. de Vicente b a Departamento de Ciencias de la Tierra, Universidad de Zaragoza, Spain b Grupo de Tectonofísica Aplicada UCM. F.C. Geológicas, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: The present-day topography of the Iberian peninsula can be considered as the result of the MesozoicCenozoic– Received 28 January 2008 tectonic evolution of the Iberian plate (including rifting and basin formation during the Mesozoic and Accepted 26 January 2009 compression and mountain building processes at the borders and inner part of the plate, during the Tertiary, Available online xxxx followed by Neogene rifting on the Mediterranean side) and surface processes acting during the Quaternary. The northern-central part of Iberia (corresponding to the geological units of the Duero Basin, the Iberian Chain, Keywords: and the Central System) shows a mean elevation close to one thousand meters above sea level in average, some Iberia Planation surface hundreds of meters higher than the southern half of the Iberian plate. This elevated area corresponds to (i) the Landscape top of sedimentation in Tertiary terrestrial endorheic sedimentary basins (Paleogene and Neogene) and Meseta (ii) planation surfaces developed on Paleozoic and Mesozoic rocks of the mountain chains surrounding the Crustal thickening Tertiary sedimentary basins. Both types of surfaces can be found in continuity along the margins of some of the Tectonics Tertiary basins. The Bouguer anomaly map of the Iberian peninsula indicates negative anomalies related to thickening of the continental crust. -

Deep Geological Conditions and Constrains for CO2 Storage in The

Proceedings of the Global Conference on Global Warming 2011 11-14 July, 2011, Lisbon, Portugal Deep Geological Conditions and Constrains for CO2 Storage in the Setúbal Peninsula, Portugal S. Machado1, J. Sampaio2, C. Rosa1, D. Rosa1, J. Carvalho3, H. Amaral2, J. Carneiro4, A. Costa2 Abstract — This paper describes the research conducted in order to identify potential CO2 storage reservoirs in the Setúbal Peninsula, Portugal. The studied area is located in the southern sector of the Lusitanian Basin, the largest Portuguese Mesozoic sedimentary basin. Data from deep geological conditions was collected from oil and gas exploration wells and structural maps of the target geological horizons were processed from seismic reflection profiles. A potential reservoir for CO2 storage in the Lower Cretaceous was identified and its volume was calculated based on kriging interpolation methods. Net-to-gross ratio and porosities were determined from geological logs. A total CO2 storage capacity of 42 Mt was estimated. However, the lack of data about the lateral continuity of the seal, the presence of the most important Portuguese groundwater resources at shallower depths and the relatively high earthquake hazard, hinders the studied reservoir from offering the necessary geological conditions for a safe CO2 storage in the studied area. Keywords — CO2 storage, reservoir and cap-rock, groundwater resources, seismicity, Portugal. ________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 INTRODUCTION existing geophysical logs, from oil and gas well The research described in this paper was carried data, from seismic reflection profiles and from out as part of the ‘COMET’ project launched reported geological studies of the reservoir under the European 7th Framework Programme, horizons where they outcrop. -

Abbreviation Kiel S. 2005, New and Little Known Gastropods from the Albian of the Mahajanga Basin, Northwestern Madagaskar

1 Reference (Explanations see mollusca-database.eu) Abbreviation Kiel S. 2005, New and little known gastropods from the Albian of the Mahajanga Basin, Northwestern Madagaskar. AF01 http://www.geowiss.uni-hamburg.de/i-geolo/Palaeontologie/ForschungImadagaskar.htm (11.03.2007, abstract) Bandel K. 2003, Cretaceous volutid Neogastropoda from the Western Desert of Egypt and their place within the noegastropoda AF02 (Mollusca). Mitt. Geol.-Paläont. Inst. Univ. Hamburg, Heft 87, p 73-98, 49 figs., Hamburg (abstract). www.geowiss.uni-hamburg.de/i-geolo/Palaeontologie/Forschung/publications.htm (29.10.2007) Kiel S. & Bandel K. 2003, New taxonomic data for the gastropod fauna of the Uzamba Formation (Santonian-Campanian, South AF03 Africa) based on newly collected material. Cretaceous research 24, p. 449-475, 10 figs., Elsevier (abstract). www.geowiss.uni-hamburg.de/i-geolo/Palaeontologie/Forschung/publications.htm (29.10.2007) Emberton K.C. 2002, Owengriffithsius , a new genus of cyclophorid land snails endemic to northern Madagascar. The Veliger 45 (3) : AF04 203-217. http://www.theveliger.org/index.html Emberton K.C. 2002, Ankoravaratra , a new genus of landsnails endemic to northern Madagascar (Cyclophoroidea: Maizaniidae?). AF05 The Veliger 45 (4) : 278-289. http://www.theveliger.org/volume45(4).html Blaison & Bourquin 1966, Révision des "Collotia sensu lato": un nouveau sous-genre "Tintanticeras". Ann. sci. univ. Besancon, 3ème AF06 série, geologie. fasc.2 :69-77 (Abstract). www.fossile.org/pages-web/bibliographie_consacree_au_ammon.htp (20.7.2005) Bensalah M., Adaci M., Mahboubi M. & Kazi-Tani O., 2005, Les sediments continentaux d'age tertiaire dans les Hautes Plaines AF07 Oranaises et le Tell Tlemcenien (Algerie occidentale). -

New Finds of Stegosaur Tracks from the Upper Jurassic Lourinhã Formation, Portugal

New finds of stegosaur tracks from the Upper Jurassic Lourinhã Formation, Portugal OCTÁVIO MATEUS, JESPER MILÀN, MICHAEL ROMANO, and MARTIN A. WHYTE Eleven new tracks from the Upper Jurassic of Portugal are the central−western part of Portugal and especially in the vicinity described and attributed to the stegosaurian ichnogenus of the small town of Lourinhã approximately 70 km north of Deltapodus. One track exhibits exceptionally well−preserved Lisboa (Fig. 1). The sediments of the Lourinhã Formation were impressions of skin on the plantar surface, showing the deposited in the Lusitanian Basin and comprise in excess of 400 stegosaur foot to be covered by closely spaced skin tubercles m of terrestrial sediments, deposited during the latest Jurassic of ca. 6 mm in size. The Deltapodus specimens from the (Late Kimmeridgian–Early Tithonian), during the initial rifting Aalenian of England represent the oldest occurrence of stage of the Atlantic Ocean (Hill 1989). stegosaurs and imply an earlier cladogenesis than is recog− The sediments predominantly consist of thick beds of red and nized in the body fossil record. green clay, interbedded with massive, fluvial sandstone bodies and heterolithic beds. The Lourinhã Formationhasyieldedanex− Introduction tensive vertebrate fauna (Lapparent and Zbyszewski 1957; Galton 1980; Antunes 1998; Antunes et al. 1998; Mateus et al. 1998, The European stegosaur track record is scarce, compared to the 2006; Antunes and Mateus 2003; Pereda−Superbiola et al. 2005; number of tracks described for other dinosaur groups. The Mateus 2006; Escaso et al. 2007) and abundant carbonized frag− track Deltapodus brodricki Whyte and Romano, 1994, descri− ments of plants and large fossilized logs (Pais 1998). -

The Lourinhã Formation: the Upper Jurassic to Lowermost Cretaceous of the Lusitanian Basin, Portugal – Landscapes Where Dinosaurs Walked

O. Mateus, et al., Ciências da Terra / Earth Sciences Journal 19 (1), 2017, 75-97 The Lourinhã Formation: the Upper Jurassic to lowermost Cretaceous of the Lusitanian Basin, Portugal – landscapes where dinosaurs walked O. Mateus1, 2, J. Dinis3 & P. P. Cunha3 1 GeoBioTec, Earth Sciences Department, Faculty of Sciences and Technology, Universidade NOVA Lisboa, Campus de Caparica. 2829-516 Caparica, Portugal. [email protected] 2 Museu da Lourinhã, Lourinhã, Portugal 3 Earth Sciences Department & IMAR Marine and Environmental Research Centre, University of Coimbra, Corresponding author: Portugal. [email protected]; [email protected] O. Mateus [email protected] Abstract Journal webpage: This work, as a fieldtrip guide, aims to provide a glimpse into the palaeoenvironments, palaeon- http://cienciasdaterra.novaidfct.pt/index. tology, and diagenesis of one of the most productive areas for Late Jurassic dinosaurs and other ver- php/ct-esj/article/view/355 tebrates in Europe, namely, the sites of the Lourinhã Formation, which is coeval with the Morrison Copyright: Formation of the midwest USA. The Late Jurassic rifting phase of the Lusitanian Basin created several sub-basins separated by © 2017 O. Mateus et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms major crustal faults. In the western and central areas of the basin, the Caldas da Rainha structure sep- and conditions of the Creative Commons arates three sub-basins with different subsidence and infill characteristics (Consolação to the west, Attribution License (CC BY), which Bombarral–Alcobaça to the northeast, and Turcifal to the southeast). The Upper Jurassic–lowermost permits unrestricted use, distribution, Cretaceous succession exposed in the coastal cliffs located between Nazaré and Santa Cruz belongs and reproduction in any medium, to the Consolação Sub-basin, whereas the coastal outcrops between Santa Cruz and Ericeira show provided the original author and source units of the Turcifal Sub-basin. -

Study of the Petroleum Potential of an Onshore Region of the Lusitanian Basin: Arruda Sub-Basin, Abadia Valley, Montejunto Anticline

Study of the petroleum potential of an onshore region of the Lusitanian Basin: Arruda Sub-basin, Abadia Valley, Montejunto Anticline Pedro, Correia Pires; Azevedo, Leonardo; Email address: [email protected]; Instituto Superior Técnico Avenida Rovisco Pais, 1 1049-001 Lisboa Abstract: Hydrocarbon reservoirs are, 1. Objective normally, associated to large geologically Using, as starting point, the existing data of complex areas. Its identification and a recent 3D seismic reflection data (acquired characterization is difficult, costly and time by Mohave, 2010) from the Montejunto area, consuming. At early stages of exploration and two 2D seismic lines acquired by and characterization studies of regional Petrogal in 1980 in the same area. It is the scope the interpretation of the available purpose of this work to map spatially the data, normally seismic reflection data, allows seismic reflections that correspond to the top the development of a geological model for a and base of the main geological formations specific sedimentary basin, or prospect. All as interpreted from detailed information the available data: composed by exploration through the available data of exploration wells, outcrops, geophysical data, or even wells drilled in this region, such as, Benfeito- studies of other areas with similar geological 1, Lapaduços-2, Freixial-1, and Aldeia background, may provide, through analogy, Grande-2. valuable information to understand the geological evolution and identify areas likely Other objective of the work developed under of accumulating hydrocarbons. The the scope of this thesis is acquiring training, Lusitanian basin is a highly geologically competences and methods regarding complex region, but is also one of the seismic interpretation from an exploratory Portuguese basins with more information point of view. -

Tracking Late Jurassic Ornithopods in the Lusitanian Basin of Portugal: Ichnotaxonomic Implications

Tracking Late Jurassic ornithopods in the Lusitanian Basin of Portugal: Ichnotaxonomic implications DIEGO CASTANERA, BRUNO C. SILVA, VANDA F. SANTOS, ELISABETE MALAFAIA, and MATTEO BELVEDERE Castanera, D., Silva, B.C., Santos, V.F., Malafaia, E., and Belvedere, M. 2020. Tracking Late Jurassic ornithopods in the Lusitanian Basin of Portugal: Ichnotaxonomic implications. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 65 (2): 399–412. The Sociedade de História Natural in Torres Vedras, Portugal houses an extensive collection of as yet undescribed dino- saur tracks with ornithopod affinities. They have been collected from different Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian–Tithonian) geological formations (Praia de Amoreira-Porto Novo, Alcobaça, Sobral, and Freixial) that outcrop along the Portuguese coast, and belong to two different sub-basins of the Lusitanian Basin (the Consolação and Turcifal sub-basins). Three main morphotypes can be distinguished on the basis of size, mesaxony and the morphology of the metatarsophalan- geal pad impression. The minute to small-sized morphotype is similar to the Anomoepus-like tracks identified in other Late Jurassic areas. The small to medium-sized morphotype resembles the Late Jurassic–Early Cretaceous ichnotaxon Dinehichnus, already known in the Lusitanian Basin. Interestingly, these two morphotypes can be distinguished qualita- tively (slightly different size, metatarsophalangeal pad impression and digit morphology) but are nevertheless difficult to discriminate by quantitatively analysing their length-width ratio and mesaxony. The third morphotype is considered a large ornithopod footprint belonging to the ichnofamily Iguanodontipodidae. This ichnofamily is typical for Cretaceous tracksites but the new material suggests that it might also be present in the Late Jurassic. The three morphotypes show a negative correlation between size and mesaxony, so the smaller tracks show the stronger mesaxony, and the larger ones weaker mesaxony.