DISCONNECTION and RECONNECTION: MISCONCEPTIONS and RECOMMENDATIONS PERTAINING to VOUCHERS in WOOD SCIENCE Jennifer Barker This P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cravens Peak Scientific Study Report

Geography Monograph Series No. 13 Cravens Peak Scientific Study Report The Royal Geographical Society of Queensland Inc. Brisbane, 2009 The Royal Geographical Society of Queensland Inc. is a non-profit organization that promotes the study of Geography within educational, scientific, professional, commercial and broader general communities. Since its establishment in 1885, the Society has taken the lead in geo- graphical education, exploration and research in Queensland. Published by: The Royal Geographical Society of Queensland Inc. 237 Milton Road, Milton QLD 4064, Australia Phone: (07) 3368 2066; Fax: (07) 33671011 Email: [email protected] Website: www.rgsq.org.au ISBN 978 0 949286 16 8 ISSN 1037 7158 © 2009 Desktop Publishing: Kevin Long, Page People Pty Ltd (www.pagepeople.com.au) Printing: Snap Printing Milton (www.milton.snapprinting.com.au) Cover: Pemberton Design (www.pembertondesign.com.au) Cover photo: Cravens Peak. Photographer: Nick Rains 2007 State map and Topographic Map provided by: Richard MacNeill, Spatial Information Coordinator, Bush Heritage Australia (www.bushheritage.org.au) Other Titles in the Geography Monograph Series: No 1. Technology Education and Geography in Australia Higher Education No 2. Geography in Society: a Case for Geography in Australian Society No 3. Cape York Peninsula Scientific Study Report No 4. Musselbrook Reserve Scientific Study Report No 5. A Continent for a Nation; and, Dividing Societies No 6. Herald Cays Scientific Study Report No 7. Braving the Bull of Heaven; and, Societal Benefits from Seasonal Climate Forecasting No 8. Antarctica: a Conducted Tour from Ancient to Modern; and, Undara: the Longest Known Young Lava Flow No 9. White Mountains Scientific Study Report No 10. -

Kingdom Class Family Scientific Name Common Name I Q a Records

Kingdom Class Family Scientific Name Common Name I Q A Records plants monocots Poaceae Paspalidium rarum C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida latifolia feathertop wiregrass C 3/3 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida lazaridis C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Astrebla pectinata barley mitchell grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cenchrus setigerus Y 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Echinochloa colona awnless barnyard grass Y 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida polyclados C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cymbopogon ambiguus lemon grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Digitaria ctenantha C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Enteropogon ramosus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon avenaceus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eragrostis tenellula delicate lovegrass C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Urochloa praetervisa C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Heteropogon contortus black speargrass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Iseilema membranaceum small flinders grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Bothriochloa ewartiana desert bluegrass C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Brachyachne convergens common native couch C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon lindleyanus C 3/3 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon polyphyllus leafy nineawn C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sporobolus actinocladus katoora grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cenchrus pennisetiformis Y 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sporobolus australasicus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eriachne pulchella subsp. dominii C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Dichanthium sericeum subsp. humilius C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Digitaria divaricatissima var. divaricatissima C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eriachne mucronata forma (Alpha C.E.Hubbard 7882) C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sehima nervosum C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eulalia aurea silky browntop C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Chloris virgata feathertop rhodes grass Y 1/1 CODES I - Y indicates that the taxon is introduced to Queensland and has naturalised. -

Pandorea Pandorana

Created by Caring for ENVIRONMENTAL Denmark’s bushland Denmark Weed Action Group Inc. for over 20 years 2014. WEED OF DENMARK SHIRE, WA Bush regeneration work on Wonga-wonga Vine public & private land Pandorea pandorana Weed identification Advice on weed control Advice on native bushland management Input into preparation of management plans Assistance with accredited training COMPILATION: Melissa Howe and Diane Harwood Preparation of successful PHOTOS: Melissa Howe grant applications Training & supervision of D e n m a r k volunteers W e e d Denmark Weed A c t i o n G r o u p I n c . Denmark Weed Action Group Inc. Action Group Inc. Street address: Denmark Weed Action 33 Strickland Street, Denmark WA 6333 Group Inc. is a not-for- Postal address: profit, community based organisation dedicated PO Box 142, Denmark WA 6333 to caring for Denmark's Phone: 0448 388 720 natural bushland. Email: [email protected] ENVIRONMENTAL WEED ENVIRONMENTAL WEED ENVIRONMENTAL WEED OF DENMARK SHIRE, WA OF DENMARK SHIRE, WA OF DENMARK SHIRE, WA Wonga-wonga vine Wonga-wonga vine Wonga-wonga vine Pandorea pandorana Pandorea pandorana Pandorea pandorana F a m i l y: BIGNONIACEAE Removal techniques I m p a c t s Cut vine stems with secateurs and, if Can form dense layers in shrub and tree Weed description practicable, locate the roots and dig them out canopy which can smother and ultimately Native to northern Western Australia, with a garden fork minimising soil kill native vegetation, dominate and Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland and disturbance. Mature plant roots can be much displace native vegetation, prevent Malaysia. -

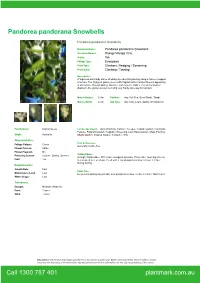

Pandorea Pandorana Snowbells

Pandorea pandorana Snowbells Pandorea pandorana Snowbells Botanical Name: Pandorea pandorana Snowbells Common Names: Wonga Wonga Vine, Native: Yes Foliage Type: Evergreen Plant Type: Climbers, Hedging / Screening Plant Habit: Climbing / Twining Description: A Vigorous and hardy native climbing vine ideal for planting along a fence or support structure. The foliage is glossy green with fragrant white trumpet flowers appearing in abundance through Spring, Summer and Autumn. Adds a very pretty tropical display to the garden as well as being very hardy and easy to maintain. Mature Height: 2-4m Position: Any, Full Sun, Semi Shade, Shade Mature Width: 2-4m Soil Type: Any, Clay, Loam, Sandy, Well Drained Family Name: Bignoniaceae Landscape Use(s): Bird Attracting, Climber / Creeper, Coastal Garden, Courtyard, Feature, Fragrant Garden, Hedging / Screening, Low Water Garden, Mass Planting, Origin: Australia Shady Garden, Tropical Garden, Container / Pot Characteristics: Pest & Diseases: Foliage Colours: Green Generally trouble free Flower Colours: White Flower Fragrant: No Cultural Notes: Flowering Season: Autumn, Spring, Summer A tough, hardy native. Will require a support structure. Prune after flowering to keep Fruit: Yes to a desired size or shape. Feed with a low phosphorus slow-release fertiliser during Spring. Requirements: Growth Rate: Fast Plant Care: Maintenance Level: Low Keep moist during dry periods, Low phosphorus slow release fertiliser, Mulch well Water Usage: Low Tolerances: Drought: Medium / Moderate Frost: Tender Wind: Tender Disclaimer: Information and images provided is to be used as a guide only. While every reasonable effort is made to ensure accuracy and relevancy of all information, any decisions based on this information are the sole responsibility of the viewer. -

Impacts of Land Clearing

Impacts of Land Clearing on Australian Wildlife in Queensland January 2003 WWF Australia Report Authors: Dr Hal Cogger, Professor Hugh Ford, Dr Christopher Johnson, James Holman & Don Butler. Impacts of Land Clearing on Australian Wildlife in Queensland ABOUT THE AUTHORS Dr Hal Cogger Australasian region” by the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union. He is a WWF Australia Trustee Dr Hal Cogger is a leading Australian herpetologist and former member of WWF’s Scientific Advisory and author of the definitive Reptiles and Amphibians Panel. of Australia. He is a former Deputy Director of the Australian Museum. He has participated on a range of policy and scientific committees, including the Dr Christopher Johnson Commonwealth Biological Diversity Advisory Committee, Chair of the Australian Biological Dr Chris Johnson is an authority on the ecology and Resources Study, and Chair of the Australasian conservation of Australian marsupials. He has done Reptile & Amphibian Specialist Group (IUCN’s extensive research on herbivorous marsupials of Species Survival Commission). He also held a forests and woodlands, including landmark studies of Conjoint Professorship in the Faculty of Science & the behavioural ecology of kangaroos and wombats, Mathematics at the University of Newcastle (1997- the ecology of rat-kangaroos, and the sociobiology of 2001). He is a member of the International possums. He has also worked on large-scale patterns Commission on Zoological Nomenclature and is a in the distribution and abundance of marsupial past Secretary of the Division of Zoology of the species and the biology of extinction. He is a member International Union of Biological Sciences. He is of the Marsupial and Monotreme Specialist Group of currently the John Evans Memorial Fellow at the the IUCN Species Survival Commission, and has Australian Museum. -

Post-Fire Recovery of Woody Plants in the New England Tableland Bioregion

Post-fire recovery of woody plants in the New England Tableland Bioregion Peter J. ClarkeA, Kirsten J. E. Knox, Monica L. Campbell and Lachlan M. Copeland Botany, School of Environmental and Rural Sciences, University of New England, Armidale, NSW 2351, AUSTRALIA. ACorresponding author; email: [email protected] Abstract: The resprouting response of plant species to fire is a key life history trait that has profound effects on post-fire population dynamics and community composition. This study documents the post-fire response (resprouting and maturation times) of woody species in six contrasting formations in the New England Tableland Bioregion of eastern Australia. Rainforest had the highest proportion of resprouting woody taxa and rocky outcrops had the lowest. Surprisingly, no significant difference in the median maturation length was found among habitats, but the communities varied in the range of maturation times. Within these communities, seedlings of species killed by fire, mature faster than seedlings of species that resprout. The slowest maturing species were those that have canopy held seed banks and were killed by fire, and these were used as indicator species to examine fire immaturity risk. Finally, we examine whether current fire management immaturity thresholds appear to be appropriate for these communities and find they need to be amended. Cunninghamia (2009) 11(2): 221–239 Introduction Maturation times of new recruits for those plants killed by fire is also a critical biological variable in the context of fire Fire is a pervasive ecological factor that influences the regimes because this time sets the lower limit for fire intervals evolution, distribution and abundance of woody plants that can cause local population decline or extirpation (Keith (Whelan 1995; Bond & van Wilgen 1996; Bradstock et al. -

South West Queensland QLD Page 1 of 89 21-Jan-11 Species List for NRM Region South West Queensland, Queensland

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

Problem Climbing Plants of Sydney's Northern Beaches

PROBLEM CLIMBING PLANTS OF SYDNEY’S NORTHERN BEACHES CONTENTS PAGE The Climbers and How to Control them, Useful Tools 1 Control Techniques 4 How Climbers Climb 4 WoNS Weeds 4 About Pittwater Natural Heritage Association 5 Some Local Native Climbers for your Garden 5 A Pittwater Natural Heritage Association publication 2018 CLIMBERS OR VINES NEED THE SUPPORT OF OTHER PLANTS TO REACH THE LIGHT Most are introduced plants gone wild, THE CLIMBERS AND HOW TO CONTROL THEM garden escapes, often from dumped garden rubbish. Arrowhead Vine/White Weedy climbers can break down and Butterfly, Syngonium podo- smother the plants they grow on. They can phyllum. Adult foliage (left) spread into bushland, destroying native juvenile “White Butterfly” form (right). Grows roots from plants. Climbers on a tree can stop it shed- stems. Cut it back to ground, ding its bark normally, causing rot. cut and paint glyphosate on each cut stem. Stems left on ground will grow and possi- They can grow fast and spread quickly, climbing and propagating themselves in vari- bly also in compost bin, so put in green waste bin. ous ways. Balloon Vine Cardiospermum grandiflorum Three of the climbers in this booklet are Usually occurs in damp places, near on the list of Weeds of National Significance water. Bin the inflated seed pods. (WoNS) because they are so damaging and Cut back to ground, cut and paint difficult to control. stumps with glyphosate or cut back and dig out. Watch out for any side- Do you have a problem with stems with roots on the ground and many seedlings. -

Available Rapid Growing Vines for the United States

ARNOLDIA A continuation of the BULLETIN OF POPULAR INFORMATION of the Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University VOLUME 4 DF.CEMBER 8, 1944 NUMBERS 9-11I AVAILABLE RAPID GROVfIN(~ VINES FOR THE UNITED STATES play a very essential part in any garden, and rapid growing vines are VINESfrequently desired for some particular purpose which no other plant material will fulfill. Sometimes they are needed only temporarily; other times they are needed permanently. Rapid growing ines are not always the most ornamental, but, since their number is rather large, some of the best will be found among them. Nor are the most ornamental vines always the easiest to obtain. Rapid growing vines that are easily obtainable are very much of interest and are in de- mand throughout the country. Consequently, this number of Arnoldia deals with those rapid growing vines, easily obtainable, that are recommended in different areas of the C’nited States. They may not all be of prime ornamental value when <·ompared with some of the rarer ones, but their rapid habit of growth makes them of considerable value for certain screening purposes. The information in this issue of Arnoldia is taken from a report prepared a short time ago when there was a great deal of interest in the camouflaging of various installations in this country, both public and private. Various horticul- turists’t mndely separated parts of the country contributed information on the * Edgar Anderson, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, Missouri W. H. Friend, Texas Agricultural Experiment Station, Weslaco, Texas Norvell Gillespie, O.C. D., San Francisco, California John Hanley, University of Washington Arboretum, Seattle, Washington A. -

The Eucalypts of Northern Australia: an Assessment of the Conservation Status of Taxa and Communities

The Eucalypts of Northern Australia: An Assessment of the Conservation Status of Taxa and Communities A report to the Environment Centre Northern Territory April 2014 Donald C. Franklin1,3 and Noel D. Preece2,3,4 All photographs are by Don Franklin. Cover photos: Main photo: Savanna of Scarlet-flowered Yellowjacket (Eucalyptus phoenicea; also known as Scarlet Gum) on elevated sandstone near Timber Creek, Northern Territory. Insets: left – Scarlet-flowered Yellowjacket (Eucalyptus phoenicea), foliage and flowers centre – reservation status of eucalypt communities right – savanna of Variable-barked Bloodwood (Corymbia dichromophloia) in foreground against a background of sandstone outcrops, Keep River National Park, Northern Territory Contact details: 1 Ecological Communications, 24 Broadway, Herberton, Qld 4887, Australia 2 Biome5 Pty Ltd, PO Box 1200, Atherton, Qld 4883, Australia 3 Research Institute for Environment and Livelihoods, Charles Darwin University, Darwin, NT 0909, Australia 4 Centre for Tropical Environmental & Sustainability Science (TESS) & School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, James Cook University, PO Box 6811, Cairns, Qld 4870, Australia Copyright © Donald C. Franklin, Noel D. Preece & Environment Centre NT, 2014. This document may be circulated singly and privately for the purpose of education and research. All other reproduction should occur only with permission from the copyright holders. For permissions and other communications about this project, contact Don Franklin, Ecological Communications, 24 Broadway, Herberton, Qld 4887 Australia, email [email protected], phone +61 (0)7 4096 3404. Suggested citation Franklin DC & Preece ND. 2014. The Eucalypts of Northern Australia: An Assessment of the Conservation Status of Taxa and Communities. A report to Kimberley to Cape and the Environment Centre NT, April 2014. -

Long Time Is Obviously Schischkin, in Proposed, Was Homonymy. 208

Miscellaneous botanical notes XVIII C.G.G.J. van Steenis A NEW FOR GASTROCALYX 115. NAME SCHISCHKIN (CARYOPHYLLACEAE) Schischkiniella — Bull. Steen., nom. nov. Gastrocalyx Schischkin, Mus. Cauc. Tifls Gardn. in Ann. Nat. Hist. based 12 (1919) 200; non Gastrocalyx Mag. I (1838) 176, on G. connatus Gardn. l.c., descr. geti.-spec. (Gentianaceae). S. ampullata (Boiss.) Steen., comb. nov. — Silene ampullata Boiss. Diagn. sér. I, 1 (1842) 26; Fl. Orient. 1 (1867) 606. — Gastrocalyx ampullata (Boiss.) Schischk. l.c. Gardner's overlooked Index which For a long time genus was in Kewensis, is obviously the reason that Dr. Schischkin, in whose honour the new name is proposed, was not aware of the homonymy. 116. THE FRUIT AND SEED OF DELTARIA BRACHYBLASTOPHORA STEEN. (THYMELAEACEAE) In 1959 I described this New Caledonian genus (Nova Guinea, n.s., 10, pt 2, p. 208) but then only oneimmaturefruit was available to me. In his new explorations Dr. McKee first and naturally continued to have interest in the plant he detected in February 1966 he sent some mature fruits and seed. He wrote that ripe fruits open very quickly and remained attached the fruit valves but were picked up below the tree; seeds to may fruit does differ also fall off soon. As can be observed (fig. 1), the mature not very much Fruits in virious Fig. 1. Deltaria brachyblastophora Steen. stages of opening, X 1½, seeds x 3. the have in size from the immature one I used for original description. In the figure I the is attached the of depicted stages of fruit opening; each of the three seeds at apex the cell and less notchlike embedded the of two valve halves. -

D.Nicolle, Classification of the Eucalypts (Angophora, Corymbia and Eucalyptus) | 2

Taxonomy Genus (common name, if any) Subgenus (common name, if any) Section (common name, if any) Series (common name, if any) Subseries (common name, if any) Species (common name, if any) Subspecies (common name, if any) ? = Dubious or poorly-understood taxon requiring further investigation [ ] = Hybrid or intergrade taxon (only recently-described and well-known hybrid names are listed) ms = Unpublished manuscript name Natural distribution (states listed in order from most to least common) WA Western Australia NT Northern Territory SA South Australia Qld Queensland NSW New South Wales Vic Victoria Tas Tasmania PNG Papua New Guinea (including New Britain) Indo Indonesia TL Timor-Leste Phil Philippines ? = Dubious or unverified records Research O Observed in the wild by D.Nicolle. C Herbarium specimens Collected in wild by D.Nicolle. G(#) Growing at Currency Creek Arboretum (number of different populations grown). G(#)m Reproductively mature at Currency Creek Arboretum. – (#) Has been grown at CCA, but the taxon is no longer alive. – (#)m At least one population has been grown to maturity at CCA, but the taxon is no longer alive. Synonyms (commonly-known and recently-named synonyms only) Taxon name ? = Indicates possible synonym/dubious taxon D.Nicolle, Classification of the eucalypts (Angophora, Corymbia and Eucalyptus) | 2 Angophora (apples) E. subg. Angophora ser. ‘Costatitae’ ms (smooth-barked apples) A. subser. Costatitae, E. ser. Costatitae Angophora costata subsp. euryphylla (Wollemi apple) NSW O C G(2)m A. euryphylla, E. euryphylla subsp. costata (smooth-barked apple, rusty gum) NSW,Qld O C G(2)m E. apocynifolia Angophora leiocarpa (smooth-barked apple) Qld,NSW O C G(1) A.