UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

*Hr03/R48* Mississippi Legislature Fifth

MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE FIFTH EXTRAORDINARY SESSION 2005 By: Representative Miles To: Sel Cmte on Hurricane Recovery HOUSE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION NO. 3 1 A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION URGING THE UNITED STATES CONGRESS TO 2 WAIVE ALL REQUIREMENTS FOR STATE OR LOCAL MATCHING FUNDS AND ALL 3 TIME LIMITS IN WHICH TO COMPLETE EMERGENCY WORK FOR DAMAGE TO THE 4 PUBLIC INFRASTRUCTURE CAUSED BY OR RESULTING FROM HURRICANE 5 KATRINA. 6 WHEREAS, on the 29th day of August, 2005, the Gulf Coast 7 region of the State of Mississippi was devastated by Hurricane 8 Katrina, a storm of historic proportions; and 9 WHEREAS, there was great loss of life and property as a 10 result of said storm; and 11 WHEREAS, the direct and indirect damage to the public 12 infrastructure of the State of Mississippi and the local 13 communities in the affected counties was immense; and 14 WHEREAS, damage estimates are now in the hundreds of millions 15 of dollars; and 16 WHEREAS, due to the enormity of the damage, normal state and 17 local procurement processes are inadequate to allow response in a 18 timely manner; and 19 WHEREAS, the extent of the damage is such that the tax base 20 of both the local communities and the state at large will be 21 adversely affected; and 22 WHEREAS, the Governor of the State of Mississippi, Governor 23 Haley Barbour, has officially requested that the President of the 24 United States waive all requirements for state or local matching 25 funds and operating assistance restrictions for projects to 26 restore the public infrastructure within the State of Mississippi 27 and provide one hundred percent federal funding for these 28 projects; and H. -

The Emergence of Parties in the Canadian House of Commons (1867-1908)

The Emergence of Parties in the Canadian House of Commons (1867-1908). Jean-Fran¸coisGodbouty and Bjørn Høylandz y D´epartement de science polititque, Universit´ede Montr´eal zDepartment of Political Science, University of Oslo Conference on the Westminster Model of Democracy in Crisis? Comparative Perspectives on Origins, Development and Responses, May 13-14, 2013. Abstract This study analyzes legislative voting in the first ten Canadian Parliaments (1867-1908). The results demonstrate that party voting unity in the House of Commons dramati- cally increases over time. From the comparative literature on legislative organization, we identify three factors to explain this trend: partisan sorting; electoral incentives; and negative agenda control. Several different empirical analyses confirm that intra-party conflict is generally explained by the opposition between Anglo-Celtic/Protestants and French/Catholic Members of Parliament. Once members begin to sort into parties according to their religious affiliation, we observe a sharp increase in voting cohesion within the Liberal and Conservative parties. Ultimately, these finding highlight the importance of territorial and socio-cultural conflicts, as well as agenda control, in ex- plaining the emergence of parties as cohesive voting groups in the Canadian Parliament. This study explains the development of party unity in the Canadian House of Commons. We take advantage of the historical evolution of this legislature to analyze a complete set of recorded votes covering the first ten parliaments (1867-1908). This early period is of interest because it was during these years that the first national party system was established, the electoral franchise was limited, and the rules and procedures of the House were kept to a minimum. -

Phoenix History Project on November 16, 1978

Arizona Historymakers™* ORAL HISTORY In Our Own Words: Recollections & Reflections Arizona Historical League, Inc. Historical League, Inc. © 2010 Historical Society BARRY M. GOLDWATER 1909-1998 Honored as Historymaker 1992 U. S. Senator and U.S. Presidential Nominee, 1964 Barry Goldwater photograph by Kelly Holcombe The following is an oral history interview with Barry Goldwater (BG) conducted by Wesley Johnson, Jr. (WJ) for the Phoenix History Project on November 16, 1978. Transcripts for website edited by members of Historical League, Inc. Original tapes are in the collection of the Arizona Historical Society Museum Library at Papago Park, Tempe, Arizona. WJ: Today it is our pleasure to interview Senator Barry Goldwater about his remembrances of Phoenix. Senator Goldwater, what is the first thing you can remember as a child about this city? BG: Well, this may seem strange to you, but the first thing I can remember was the marriage of Joe Meltzer, Sr. because I was the ring bearer. It was being held at the old Women’s Club at Fillmore, which was about Fillmore and First Avenue. I remember I was only about four years old, standing outside waiting for the telegraph boy to bring a message saying that President Taft had signed us into statehood. It was Joe Meltzer’s determination to be the first man married in the State of Arizona. Sure enough, I can still see that dust coming up old unpaved First Avenue with the messenger with the telegram. Then we marched in and had the wedding. WJ: That’s interesting. I interviewed Mr. Meltzer and he told me that story from his perspective. -

League of Women Voters Is a National Nonpartisan Grand Traverse County Districts 4-Year Term, All Expire 1/20/21 Political Organization Established in 1920

NATIONAL OFFICIALS About the League GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS 116th Congress U.S. Congressional The League of Women Voters is a national nonpartisan Grand Traverse County Districts 4-year term, all expire 1/20/21 political organization established in 1920. League of Women Feb 2020 President: Donald Trump (R-New York)..........(202) 456-1414 1st Bergman (R) Voters encourages informed and active participation in The White House Washington, DC 20500 4th Moolenaar (R) government, works to increase understanding of major public Vice President: Michael Pence (R-Indiana) 5th Kildee (D) policy issues and influences public policy through education and advocacy. The League is financed by member dues and UNITED STATES SENATORS contributions from members and others. Membership is open 100 (47 Dem - 53 Rep) to all citizens of voting age. 6-year staggered term For more information: Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 Phone: 231-633-5819 Write: LWV-GTA, PO Box 671, Traverse City, Ml 49685 Gary C Peters (D-Bloomfield Twp) 1/3/21 ......(202) 224-6221 Website: www.lwvgta.org Fax: (313) 226-6948, (844) 506-7420, (231) 947-7773 State Senate The League of Women Voters is where www.peters.senate.gov Districts hands on work to safeguard democracy 35th Curt VanderWall (R) leads to civic improvement. Debbie Stabenow (D-Lansing) 1/3/25 .............(202) 224-4822 36th Stamas (R) Fax: (231) 929-1250, (231) 929-1031 37th Schmidt (R) Voting Information www.stabenow.senate.gov • You are elibible to register and vote if you are a US US HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Citizen, at least age 18 by election day. -

Parliaments and Legislatures Series Samuel C. Patterson

PARLIAMENTS AND LEGISLATURES SERIES SAMUEL C. PATTERSON GENERAL ADVISORY EDITOR Party Discipline and Parliamentary Government EDITED BY SHAUN BOWLER, DAVID M. FARRELL, AND RICHARD S. KATZ OHI O STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS COLUMBUS Copyright © 1999 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Party discipline and parliamentary government / edited by Shaun Bowler, David M. Farrell, and Richard S. Katz. p. cm. — (Parliaments and legislatures series) Based on papers presented at a workshop which was part of the European Consortium for Political Research's joint sessions in France in 1995. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8142-0796-0 (cl: alk. paper). — ISBN 0-8142-5000-9 (pa : alk. paper) 1. Party discipline—Europe, Western. 2. Political parties—Europe, Western. 3. Legislative bodies—Europe, Western. I. Bowler, Shaun, 1958- . II. Farrell, David M., 1960- . III. Katz, Richard S. IV. European Consortium for Political Research. V. Series. JN94.A979P376 1998 328.3/75/ 094—dc21 98-11722 CIP Text design by Nighthawk Design. Type set in Times New Roman by Graphic Composition, Inc. Printed by Bookcrafters, Inc.. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 98765432 1 Contents Foreword vii Preface ix Part I: Theories and Definitions 1 Party Cohesion, Party Discipline, and Parliaments 3 Shaun Bowler, David M. Farrell, and Richard S. Katz 2 How Political Parties Emerged from the Primeval Slime: Party Cohesion, Party Discipline, and the Formation of Governments 23 Michael Laver and Kenneth A. -

Chapter One: Postwar Resentment and the Invention of Middle America 10

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Jeffrey Christopher Bickerstaff Doctor of Philosophy ________________________________________ Timothy Melley, Director ________________________________________ C. Barry Chabot, Reader ________________________________________ Whitney Womack Smith, Reader ________________________________________ Marguerite S. Shaffer, Graduate School Representative ABSTRACT TALES FROM THE SILENT MAJORITY: CONSERVATIVE POPULISM AND THE INVENTION OF MIDDLE AMERICA by Jeffrey Christopher Bickerstaff In this dissertation I show how the conservative movement lured the white working class out of the Democratic New Deal Coalition and into the Republican Majority. I argue that this political transformation was accomplished in part by what I call the "invention" of Middle America. Using such cultural representations as mainstream print media, literature, and film, conservatives successfully exploited what came to be known as the Social Issue and constructed "Liberalism" as effeminate, impractical, and elitist. Chapter One charts the rise of conservative populism and Middle America against the backdrop of 1960s social upheaval. I stress the importance of backlash and resentment to Richard Nixon's ascendancy to the Presidency, describe strategies employed by the conservative movement to win majority status for the GOP, and explore the conflict between this goal and the will to ideological purity. In Chapter Two I read Rabbit Redux as John Updike's attempt to model the racial education of a conservative Middle American, Harry "Rabbit" Angstrom, in "teach-in" scenes that reflect the conflict between the social conservative and Eastern Liberal within the author's psyche. I conclude that this conflict undermines the project and, despite laudable intentions, Updike perpetuates caricatures of the Left and hastens Middle America's rejection of Liberalism. -

Counting Parties and Identifying Dominant Party Systems in Africa

European Journal of Political Research 43: 173–197, 2004 173 Counting parties and identifying dominant party systems in Africa MATTHIJS BOGAARDS International University Bremen, Germany Abstract. By most definitions, the third wave of democratisation has given rise to dominant parties and dominant party systems in Africa. The effective number of parties, the most widely used method to count parties, does not adequately capture this fact. An analysis of 59 election results in 18 sub-Saharan African countries shows that classifications of party systems on the basis of the effective number of parties are problematic and often flawed. Some of these problems are well known, but the African evidence brings them out with unusual clarity and force. It is found that Sartori’s counting rules, party system typology and definition of a dominant party are still the most helpful analytical tools to arrive at an accu- rate classification of party systems and their dynamics in general, and of dominant party systems in particular. Introduction Multi-party elections do not lead automatically to multi-party systems. In sub- Saharan Africa, the spread of multi-party politics in the 1990s has given rise to dominant parties. A majority of African states has enjoyed multi-party elec- tions, but no change in government (Bratton & van de Walle 1997; Baker 1998; Herbst 2001; Cowen & Laakso 2002). In some countries where a change in government did take place, the former opposition is by now well entrenched in power. This has led to the prediction of an ‘enduring relevance of the model of single-party dominance’ (O’Brien 1999: 335). -

Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential Election Matthew Ad Vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2011 "Are you better off "; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election Matthew aD vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Caillet, Matthew David, ""Are you better off"; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election" (2011). LSU Master's Theses. 2956. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2956 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ―ARE YOU BETTER OFF‖; RONALD REAGAN, LOUISIANA, AND THE 1980 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History By Matthew David Caillet B.A. and B.S., Louisiana State University, 2009 May 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people for the completion of this thesis. Particularly, I cannot express how thankful I am for the guidance and assistance I received from my major professor, Dr. David Culbert, in researching, drafting, and editing my thesis. I would also like to thank Dr. Wayne Parent and Dr. Alecia Long for having agreed to serve on my thesis committee and for their suggestions and input, as well. -

USSYP 2010 Yearbook.Pdf

THE HEARST FOUNDATIONS DIRECTORS William Randolph Hearst III UNTED STATE PESIDENTR James M. Asher Anissa B. Balson David J. Barrett S Frank A. Bennack, Jr. SE NAT E YO John G. Conomikes Ronald J. Doerfler George R. Hearst, Jr. John R. Hearst, Jr. U Harvey L. Lipton T Gilbert C. Maurer H PROGR A M Mark F. Miller Virginia H. Randt Paul “Dino” Dinovitz EXCUTIE V E DIRECTOR F ORT Rayne B. Guilford POAR GR M DI RECTOR Y - U N ITED S TATES SE NATE YOUTH PROGR A M E IGHT H A N N U A L WA S H INGTON WEEK 2010 sponsored BY THE UNITED STATES SENATE UNITED STATES SENATE YOUTH PROGRAM FUNDED AND ADMINISTERED BY THE THE HEARST FOUNDATIONS FORTY-EIGHTH ANNUAL WASHINGTON WEEK H M ARCH 6 – 1 3 , 2 0 1 0 90 NEW MONTGOMERY STREET · SUITE 1212 · SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94105-4504 WWW.USSENATEYOUTH.ORG Photography by Jakub Mosur Secondary Photography by Erin Lubin Design by Catalone Design Co. “ERE TH IS A DEBT OF SERV ICE DUE FROM EV ERY M A N TO HIS COUNTRY, PROPORTIONED TO THE BOUNTIES W HICH NATUR E A ND FORTUNE H AV E ME ASURED TO HIM.” —TA H O M S J E F F E R S ON 2010 UNITED STATES SENATE YOUTH PROGR A M SENATE A DVISORY COMMITTEE HONOR ARY CO-CH AIRS SENATOR V ICE PRESIDENT SENATOR HARRY REID JOSEPH R. BIDEN MITCH McCONNELL Majority Leader President of the Senate Republican Leader CO-CH AIRS SENATOR SENATOR ROBERT P. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2018 Remarks At

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2018 Remarks at the Ohio Republican Party State Dinner in Columbus, Ohio August 24, 2018 The President. Thank you very much, everybody. It's great to be back here. Remember, you cannot win unless you get the State of Ohio. Remember that? I heard that so many times. "You need the State of Ohio; therefore Trump can't win." I think we won by 9 points. What did we win by? Nine? We're winning. We're going to keep winning. I love this State. I worked here. During a summer, I worked here, and I loved it. Cincinnati. We like Cincinnati. Right? [Applause] We like Cincinnati. And this November, we're going to win really big. It's going to be one big Ohio family, as we've had. Special place. Helping us to achieve that victory will be our incredible Ohio GOP Chairwoman—a really incredible person and friend of mine—Jane Timken. Thank you, Jane. Great to be with you, Jane. Great job. This is your record—alltime. This is the all—that's not bad. You know, it is Ohio. All-time record. I'd say that's pretty good. We're also joined tonight by RNC Cochairman Bob Paduchik, who also ran my campaign in Ohio. And I want to tell you, he did an awfully good job. He did a great job. Thank you, Bob. Fantastic. I also want to express my gratitude to all of the county GOP chairs, grassroots activists, volunteers, and Republican women who work so hard to achieve victory for your party, your State, and for your country. -

2013 Complete List of Elected Officials Pulaski County.Xlsx

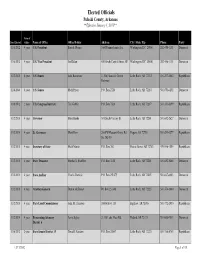

Elected Officials Pulaski County, Arkansas **Effective January 1, 2013** Term of Date Elected Office Name of Office Office Holder Address City/ State/ Zip Phone Party 11/6/2012 4 year U.S. President Barack Obama 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. Washington, DC 20500 202-456-1111 Democrat 11/6/2012 4 year U.S. Vice President Joe Biden 430 South Capitol Street, SE Washington, DC 20500 202-456-1111 Democrat 11/2/2010 6 year U.S. Senate John Boozman 11300 Financial Centre Little Rock, AR 72211 501-227-0062 Republican Parkway 11/4/2008 6 year U.S. Senate Mark Pryor P.O. Box 2720 Little Rock, AR 72203 501-551-0292 Democrat 11/6/2012 2 year U.S. Congress District 2 Tim Griffin P.O. Box 7526 Little Rock, AR 72217 501-353-0899 Republican 11/2/2010 4 year Governor Mike Beebe 301 South Victory St Little Rock, AR 72201 501-682-2627 Democrat 11/2/2010 4 year Lt. Governor Mark Darr 2605 W Pleasant Grove Rd Rogers, AR 72758 501-291-3277 Republican Ste 202-50 11/2/2010 4 year Secretary of State Mark Martin P.O. Box 700 Prairie Grove, AR 72753 479-846-1889 Republican 11/2/2010 4 year State Treasurer Martha A. Shoffner P.O. Box 3020 Little Rock, AR 72201 501-682-5888 Democrat 11/2/2010 4 year State Auditor Charlie Daniels P.O. Box 250275 Little Rock, AR 72225 501-847-0063 Democrat 11/2/2010 4 year Attorney General Dustin McDaniel PO Box 251368 Little Rock, AR 72225 501-374-6000 Democrat 11/2/2010 4 year State Land Commissioner John M. -

Twelve Elections That Shaped a Century I Tawdry Populism, Timid Progressivism, 1900-1930

Arkansas Politics in the 20th Century: Twelve Elections That Shaped a Century I Tawdry Populism, Timid Progressivism, 1900-1930 One-gallus Democracy Not with a whimper but a bellow did the 20th century begin in Arkansas. The people’s first political act in the new century was to install in the governor’s office, for six long years, a politician who was described in the most graphic of many colorful epigrams as “a carrot-headed, red-faced, loud-mouthed, strong-limbed, ox-driving mountaineer lawyer that has come to Little Rock to get a reputation — a friend of the fellow who brews forty-rod bug juice back in the mountains.”1 He was the Tribune of the Haybinders, the Wild Ass of the Ozarks, Karl Marx for the Hillbillies, the Stormy Petrel, Messiah of the Rednecks, and King of the Cockleburs. Jeff Davis talked a better populism than he practiced. In three terms, 14 years overall in statewide office, Davis did not leave an indelible mark on the government or the quality of life of the working people whom he extolled and inspired, but he dominated the state thoroughly for 1 This quotation from the Helena Weekly World appears in slightly varied forms in numerous accounts of Davis's yers. It appeared in the newspaper in the spring of 1899 and appears in John Gould Fletcher, Arkansas (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1947) p. 2. This version, which includes the phrase "that has come to Little Rock to get a reputation" appears in Raymond Arsenault, The Wild Ass of the Ozarks: Jeff Davis and the Social Bases of Southern Politics (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1984), p.