FF 2016-1 Pages @ A4 Inc Covers CUT.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valid List by Design

Date: 10/19/2012 2012 Valid List by Design, Adjustments Page 1 of 31 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish handicaps for any other boats not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap. Design Last Name Yacht Name Record Date Base LP Adj Spin Rig Prop Rec Misc Race Cruise 1 D35 Schimenti Zefiro Toma R043012 36 -9 -3 24 42 12 Metre Gregory Valiant R071212 3 +6 9 9 12 Metre Mc Millen 111 Onawa R011512 33 -6 27 33 5.5 Carney Lyric R082912 156 u156 u165 8 Metre Palm Quest N071612 111 111 117 Aerodyne 38 D' Alessandro Alexis R053112 39 39 48 Akilaria Class 40 Davis Amhas R072312 -9 -9 -3 Akilaria Class 40 Dreese Toothface R041012 -9 -9 0 Alben 54 Ketch Wiseman Legacy V R070212 57 +6 +6 69 78 Alberg 35 Prefontaine Helios R042312 201 -3 198 210 Alberg 37 Mintz L' Amarre R061612 156 +6 +3 +6 171 186 Albin Cumulus Droste Cumulus 3 R030412 189 189 204 Albin Nimbus 42 Pomfret Anne R052212 99 99 111 Alden 42 S D S M Vieira Cadence R011312 120 +6 +6 132 144 Alden 44 Rice Pilgrim N053112 111 +9 +6 126 141 Alden 44 Weisman Nostos R011312 111 +9 +6 126 132 Alden 45 Davin Querence R071912 87 +9 +6 102 108 Alden 45" Seagoer Dunne Cygnet N040212 141 141 147 Alerion 26 Lurie Mischief R040612 225 U225 U231 Alerion Express 28 Brown Lumen Solare C082212 -

C O N T E N T S

PRST STD US Postage Paid Permit, #454 THE STATE OF MAINE'S BOATING NEWSPAPER Portland, ME Maine Coastal News Volume 33 Issue 4 April 2020 FREE Another Good Year for Boatbuilders and Repair Yards! MISTER E., a Calvin Beal 44, finished off as a lobster boat for Nicko Hadlock of Cranberry Isle by S. W. Boatworks of Lamoine. She is powered with a 750-hp John Deere, with a 2.48:1 gear, and reached a speed of 23 knots. Belmont Boatworks Down in the paint shop they are Awl- Belmont gripping a number of boat parts for a local For years Belmont Boats was only customer. known for doing boat transportation, but As the winter progressed they have been now they are gaining a fine reputation in bringing in some of their storage boats and boat repairs and painting. getting them ready for the season. Most of The repair work continues on MAL- this work has been small repairs and paint. ACHI MUDGE, a 42-foot pleasure cruiser They also have several jobs coming built by Newbert & Wallace of Thomaston in. One will be in for some planking; and in 1958. They have replaced the windshield, another is on the Holland 32 they worked on put in a new cockpit hatch and the painting last winter, which will be in for some interior continues. A recent survey also showed that upgrades. she will need some refastening below the waterline and that will be done when they C. W. Hood drop the tent that is surrounding her hull Marblehead keeping her moist so she does not dry out. -

The Journal of the Ocean Cruising Club

2016/1 The Journal of the Ocean Cruising Club 1 Boatyard Or Backyard Rolling and Tipping with Epifanes Delivers Exceptional Results. Professional or amateur, once you’ve rolled and tipped a boat with Epifanes two-part Poly-urethane, it will be your go-to strategy for every paint job. The results are stunning, and Epifanes’ tech support is unsurpassed. Still great for spraying, but Epifanes roll-and-tip is the proven shortcut to a durable, mirror-like finish. Yacht Coatings AALSMEER, HOLLAND Q THOMASTON, MAINE Q ABERDEEN, HONG KONG +1 207 354 0804 Q www.epifanes.com FOLLOW US A special thank-you to the owners of Moonmaiden II. Beautiful paint job. 2 OCC FOUNDED 1954 offi cers COMMODORE Anne Hammick VICE COMMODORES Tony Gooch REAR COMMODORES Dick Guckel Peter Paternotte REGIONAL REAR COMMODORES GREAT BRITAIN Chris & Fiona Jones IRELAND John Bourke NORTH WEST EUROPE Claus Jaeckel NORTH EAST USA Denis Moonan & Pam MacBrayne SOUTH EAST USA Bob & Janellen Frantz WEST COAST NORTH AMERICA Ian Grant NORTH EAST AUSTRALIA Nick Halsey SOUTH EAST AUSTRALIA Paul & Lynn Furniss ROVING REAR COMMODORES Scott & Kitty Kuhner, John & Christine Lytle, Chris Cromey & Suzanne Hills, Simon Fraser & Janet Gayler, Martin & Elizabeth Bevan, Rick & Julie Palm, David & Juliet Fosh, Jack & Zdenka Griswold, Franco Ferrero & Kath McNulty, Jonathan & Anne Lloyd PAST COMMODORES 1954-1960 Humphrey Barton 1960-1968 Tim Heywood 1968-1975 Brian Stewart 1975-1982 Peter Carter-Ruck 1982-1988 John Foot 1988-1994 Mary Barton 1994-1998 Tony Vasey 1998-2002 Mike Pocock 2002-2006 -

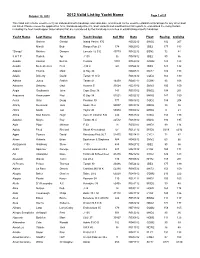

Valid List by Yacht Name Page 1 of 25

October 19, 2012 2012 Valid List by Yacht Name Page 1 of 25 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish a handicaps for any other boat not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap Yacht Name Last Name First Name Yacht Design Sail Nbr Date Fleet Racing Cruising Gartner Gerald Island Packet 370 R052212 BWS2 192 207 Minelli Bob Ranger Fun 23 174 N062012 JBE2 177 183 "Sloopy" Melcher Dwayne Lacoste 42 S E 40779 R042212 BSN2 72 84 5 H T P Rudich Api J 105 96 R081812 JBE2 90 96 Acadia Keenan Burt H. Custom 1001 R062912 GOM2 123 123 Acadia Biebesheimer Fred J 34 C 69 R052412 JBE2 123 132 Adagio Thuma Mark O Day 30 N040512 MAT2 186 198 Adajio Doherty David Tartan 31 S D R061612 COD2 165 180 Adhara Jones Patrick Tartan 41 14459 R040212 GOM2 93 108 Advance Delaney Ged Avance 33 33524 R021312 SMV2 150 159 Aegis Gaythwaite John Cape Dory 36 141 R051012 BWS2 198 201 Aequoreal Rasmussen Paul O Day 34 51521 R032212 MRN2 147 159 Aerial Gray Doug Pearson 30 777 N061612 COD2 189 204 Affinity Desmond Jack Swan 48-2 50007 R042312 MRN2 33 36 Africa Smith Jud Taylor 45 50974 R030812 MHD2 9 21 Aftica Mac Kenzie Hugh Irwin 31 Citation S D 234 R061512 COD2 183 198 Agadou Mayne Roy Tartan 34 C 22512 R061812 MAN2 180 195 Agila Piper Michael E 33 18 R050912 MHD2 -

Hinckley Sail Line Is the Sou’Wester 61

H INCKLEY SAIL THE LAUNCH of a new Sou’wester® is a much-anticipated event along the waterfront of Southwest Harbor, Maine. It marks the end of one journey: within the Hinckley workshops, where she passed through the experienced hands of Hinckley hull makers, carpenters and smiths. It signals the beginning of another: a journey upon the seas, where its competence and composure will be prized both by those who aim to race, and those who wish merely to relax. And with each launch, Henry Hinckley’s legacy of innovation and excellence is renewed. IN THE SEVEN DECADES since “The Yard” was founded, the Hinckley name has come to represent the continual advancement of nautical design and manufacturing. Each new yacht to emerge from Shore Road A TIMELINE OF NAUTICAL INNOVATION. carries with it the Hinckley symbol, Talaria, derived from the wings adorning the ankles of the Roman god, Mercury — a testament to the company’s swift pursuit of superior ideas. 1928 1944 1956 1960 1973 1991 1994 1995 1999 2005 Henry Hinckley Hinckley contributes Hinckley becomes one The Bermuda 40 is Hinckley is one of the Hinckley becomes the After four years Hinckley introduces Hinckley pioneers The art of day sailing is establishes “The Yard” to the war effort, of the first production launched — a masterful early adopters of roller first American builder of tank testing, the the Sou’wester 70, a DualGuard composite advanced to new levels in Southwest Harbor, launching the first of builders to recognize union of new fiberglass furling headsails and to convert entirely to Picnic Boat® sprints up Bruce King design that construction, the of speed and ease with Maine. -

40' Hinckley Bermuda 1970

http://www.yachtworld.com/westyachts West Yachts LLC - Russ Meixner Tel: 360-299-2526 West Yachts , West Yachts LLC , Fax: 360-299-3193 1019 Q. Ave. Suite D [email protected] Anacortes, WA 98221, United States Hinckley Bermuda 40 • Year: 1970 • Price: $ 125,000 • Location: Anacortes, WA, United States • Hull Material: Fiberglass • Fuel Type: Diesel • YachtWorld ID: 3709046 • Condition: Used New Yanmar Diesel in 2014 with Only 170 Hours!!! Mahagony interior and sleeps six in two cabins Forward owner's stateroom offers V-berths with storage and tankage below. Hanging locker aft to starboard, bureau, bookshelves and overhead opening hatch. Moving aft to port a head. Hanging locker and storage locker. Main cabin features salon amidships with straight settees forward to port and starboard,each of which slides out to make a berth and drawers under. Each with a pilot berth outboard and over. Drop leaf dining table is center-line. L-shaped galley aft to port with refrigerator compartment and locker stowage opposite to starboard. Steps inboard of galley are removable for engine access, lead up and aft to the cockpit. Navigation station is starboard of the companionway with chart storage above. Dimensions LOA: 46 ft Beam: 11 ft 9 in Number of Heads: 1 Engines Engine #1 Engine Make: Yanmar Engine Model: 3JH5E Primary Engines: Inboard Drive Type: Direct Drive Location: Center Engine Year: 2014 Hours: 170 Power: 40 hp Propeller Type: 3 Blade Propeller Material: Bronze Specifications: • LOA - 46' • LOD - 40' 9" • LWL - 28' 10" • Beam - 11' 9" • Draft - Centerboard Up 4' 1" / Centerboard Down 8' 7" • Displacement - 20,000lbs. -

Newport Bermuda 2018

BERMU RT DA O R P A W C E E N 2018 NEWPORT BERMUDA 2018 JUNE 15, 2018 OFFICIAL PROGRAM PLEASE DRINK DELICIOUSLY. BERMUDA RACE ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Jonathan Brewin - Chairman John R. “Jay” Gowell - Vice Chairman Stephen W. Kempe - Vice Chairman David Benevides V/C RBYC CONTENTS Bruce Berriman James G. Binch IPC/CCA W. Frank Bohlen John E. Brooks Peter L. Chandler CCA Treasurer THE RACE CHAIRMAN’S LETTER Jon Corless RBYC Commodore 5 Robert S. Darbee III Jonathan Brewin Frederick W. Deichmann H.L DeVore LETTERS FROM THE COMMODORES Alton J. Evans, Jr. 7 Brad Willauer, Jonathan Corless Edwin G. Fischer Jeffrey L. Eberle NBR Treasurer PREVIEW OF THE 51ST NEWPORT BERMUDA Janet Garnier 8 Ernest L. Godshalk Chris Museler Henry F. Halsted Richard S. “Rush” Hambleton III YOUNG & FAST ON BLUE WATER Paul J. Hamilton 15 John Burnham ERM Joe Harris RT B UDA O R Richard C. Holliday P A FORECAST SURPRISES, NEWPORT BERMUDA 2016 W C Bjorn R. Johnson E E 18 N Somers Kempe W. Frank Bohlen Mark R. Lenci Michael McBee SEASICKNESS: COMMON, CURABLE, PREVENTABLE Christopher J. McNally 24 Jeffrey S. Wisch, M.D. Tristan Mouligne 2018 Ralph J. Naranjo ROUND-TRIP PREPARATION OFFICIAL RUM Lester E. “Nick” Nicholson Jr. John D. Osmond III 28 Sheila McCurdy Christopher L. Otorowski CCA Secretary James D. Phyfe III SMELL THE SARGASSO John Rousmaniere 32 Gardiner L. “Garry” Schneider Andrew Burton Leslie Schneider Mark Smith RBYC Treasurer OFFICIAL NOTICE BOARD AT BERMUDARACE.COM Peter Shrubb 35 Media Team James R. Teeters W. Bradford Willauer CCA Commodore ONION PATCH SERIES REWARDS ALL-AROUNDERS John S. -

Issue I’Ve Tried to Look Back a Bit, Even Thought I’D Zealand

THE CONCORDIAN A NEWSLETTER FOR LOVERS OF CONCORDIA YacHTS SPRING 2013, NUMBER 54 JAVA No. 1 Brooklin, ME turn of the bilge. The original spars were repaired and splined where the old glue joints had failed. All new spliced rigging The 75th is here and it is important to comment on JAVA’s was installed by Concordia’s old rigger. She sported a new set legacy. As newlyweds we cruised on the Concordia White Cap of sails. A custom Concordia holding tank was installed along No. 47, now Ariadne, on Buzzards Bay and the mystique stuck with a new Concordia heating stove and a Concordia folding with us. Years later the International Yacht Restoration School pipe berth on the port side forward. Original Concordia light received JAVA as a donation; later on she was offered for sale fixtures were installed, and a new Yanmar diesel completed the by IYRS, and we subsequently agreed to buy her. JAVA was picture. still under full restoration by a team of IYRS grads and two From then on to the last couple of years we cruised JAVA skilled shipwrights. At that point her hull was complete and in Maine waters, raced in three ERR events and enjoyed the ready for decking; just about half finished. From then on were whole Concordia experience, as we knew we would. It was actively involved with her restoration. All the IYRS people always a thrill to realize that we were at the same cabin table were really wonderful to work with; it was a very nice experi- that Llewellyn Howland used when he cruised on Buzzards ence for us during the whole project. -

Good Old Boat Articles by Category

Good Old Boat articles by category Feature boats Cape Dory 30, Number 1, June 1998 Ericson 35, Number 2, Sept. 1998 Niagara 35, Number 3, Nov. 1998 Blackwatch 19, Number 4, Jan. 1999 Baba 30, Number 5, Mar. 1999 Pearson Commander/Ariel, Number 6, May 1999 Block Island 40, Number 7, July 1999 Nicholson 35, Number 8, Sept. 1999 Bayfield 40, Number 9, Nov. 1999 C&C Redwing 30, Number 10, Jan. 2000 Tanzer 22, Number 11, Mar. 2000 Morgan 38, Number 12, May 2000 Classic sailboats (Bermuda 40, Valiant 40, Cherubini 44), Number 12, May 2000 West Wight Potter, Number 13, July 2000 Allied Seabreeze, Number 14, Sept. 2000 Ericson 36C, Number 15, Nov. 2000 Seven Bells (part 1), Number 15, Nov. 2000 Seven Bells (part 2), Number 16, Jan. 2001 Catalina 22, Number 17, Mar. 2001 Cheoy Lee Offshore 40, Number 18, May 2001 Lord Nelson 35, Number 19, July 2001 Tartan 33, Number 20, Sept. 2001 Stone Horse, Number 22, Jan. 2002 Sea Sprite 34, Number 23, Mar. 2002 Sabre 30, Number 24, May 2002 Columbia 28, Number 25, July 2002 Cheoy Lee 35, Number 26, Sept. 2002 Nor'Sea 27, Number 27, Nov. 2002 Allied Seawind 30, Number 28, Jan. 2003 Bristol 24, Number 29, Mar. 2003 Montgomery 23, Number 30, May 2003 Victoria 18, Number 31, July 2003 Bristol 35.5 Number 32, September, 2003 Eastward Ho 31, Number 33, November, 2003 Ericson 29, Number 34, January 2004 Watkins 29, Number 36, May 2004 Spencer 35, Number 38, September 2004 Pacific Seacraft/Crealock 37, Number 39, November 2004 Cheoy Lee 32, Number 40, January 2005 Tayana 37, Number 41, March 2005 Bristol 29.9, Number 43, July 2005 Cape Dory 25, Number 45, November 2005 Lazy Jack 32, Number 46, January 2006 Alberg 30, Number 47, March 2006 Ranger 28, Number 50, September 2006 Allegra 24, Number 51, November 2006 Finisterre's sister, Number 52, January 2007 Islander 30, Number 53, March 2007 Review boats Albin Vega, Number 5, March 1999 Bristol Channel Cutter, Number 6, May 1999 Cal 20, Number 7, July 1999 Contessa 26, Number 8, Sept. -

Cruising with Grandkids What's New at Noroton YC? Racing Roundup

Sailing the Northeast CruisingCruising withwith GrandkidsGrandkids What’sWhat’s NewNew atat NorotonNoroton YC?YC? RacingRacing RoundupRoundup October 2018 • FREE windcheckmagazine.com MCMICHAEL YACHT BROKERS Experience counts. Mamaroneck, NY 10543 Newport, RI 02840 914-381-5900 401- 619 - 5813 List your boat with McMichael and be part of the Northeast’s largest selection of quality new and brokerage boats Six brokers, three offices and two yards mean McMichael has you covered! Since Since Since Hanse 418 in stock and on display Dehler 38 in stock and on display at the Annapolis Boat Show at the Annapolis Boat Show The MJM 40z Downeast express J/121 on order and on display at cruiser. Stock boat on order the Annapolis Boat Show Discounted winter storage available for brokerage boats! Our display of brokerage yachts is a destination for boat shoppers year round. www.mcmyacht.com publisher's log Back to work (and school)! Sailing the Northeast Issue 180 Phew! It feels like these last two months, August and September, were like a mad scramble to enjoy summer while it lasted. Junior sailing wrapped up, Publisher Benjamin Cesare family vacations happened in August, then the big, season ending or [email protected] championship regattas all went down in September. (And due to that family Publisher Emerita vacation, you may not have been as prepared as you would have liked!) Anne Hannan Cruisers and day sailors were out trying to milk the last few nice weekends [email protected] and evenings before the non-stop string of low pressure systems rolled Editor-at-Large through. -

PHRF Ratings Summary Updated: 09/05/20

FCSA - PHRF Ratings Summary Updated: 09/05/20 For your individual certificate, type in the URL Bar the following: www.sailjax.com/2020/Certs/BOAT-NAME.pdf 700 / 700 / (upper/lower case matters) (550+Spin) (550+NSpin) Sail # Boat Name Spin N-Spin TCF TCF-NsP Boat Make Base Club First Last 95 ACTAEA 183 201 0.9550 0.9321 HINCKLEY BERMUDA 40 MkII Yawl 177 Rat Island ANTHONY HARWELL 1 41038 ADVENTURE 117 138 1.0495 1.0174 C&C 38-3 CB 108 SAYC DENISE SMITH 2 4 ALCHEMIST 54 74 1.1589 1.1218 JEANNEAU SUN FAST 3300 54 SAS MIKE COE 3 49 ALLONS-Y 144 163 1.0086 0.9818 JEANNEAU 349 135 SAS CHUCK POINTS 4 386 ARIEL 156 172 0.9915 0.9695 HUNTER 386 SD 141 SAYC DANIEL FLORYAN 5 11732 AUGUSTA BELLE 270 290 0.8537 0.8333 CATALINA 22 270 SAYC LAWRENCE MacCORMACK 6 83272 AVENGER 102 120 1.0736 1.0448 CARRERA 290 (Mod) 96 NFCC GARY VAN TASSEL 7 67 BERNOULLI 144 165 1.0086 0.9790 PEARSON 36-2 CB 132 EFYC, NFCC ALLEN JONES 8 31706 BIGTIME 129 150 1.0309 1.0000 S-2 10.3 117 NFCC DAVID PARRISH 9 114 BLUE SKY 177 199 0.9629 0.9346 C&C 32 CB 171 SAYC DANA HUNTER 10 60382 BREEZING UP 144 166 1.0086 0.9777 BENETEAU OC 423 132 PCYC ROBERT MAHER 11 485 CALYPSO 264 278 0.8600 0.8454 STARWIND 223 264 None PHILIP FILIPOV 12 1969 CALYPSO BREEZE 162 182 0.9831 0.9563 MORGAN 41 CB 144 PYC CAROLYN BALL 13 81 CAPER 201 223 0.9321 0.9056 PEARSON 35 KETCH 180 NFCC PETER KOROUS 14 473 CHASSEUR 114 142 1.0542 1.0116 PETERSON 34 (Mod) 114 SAYC GEORGE FORRESTER 15 40168 CHEETAH 120 141 1.0448 1.0130 J-29 MH IB 120 RCoJ BUBBA FUTCH 16 407 COMPASS ROSE 261 279 0.8631 0.8444 CAPE -

11 Meter Od Odr *(U)* 75 1D 35 36 1D 48

11 METER OD ODR *(U)* 75 1D 35 36 1D 48 -42 30 SQUARE METER *(U)* 138 5.5 METER ODR *(U)* 156 6 METER ODR *(U)* Modern 108 6 METER ODR *(U)* Pre WW2 150 8 METER Modern 72 8 METER Pre WW2 111 ABBOTT 33 126 ABBOTT 36 102 ABLE 20 288 ABLE 42 141 ADHARA 30 90 AERODYNE 38 42 AERODYNE 38 CARBON 39 AERODYNE 43 12 AKILARIA class 40 RC1 -6/3 AKILARIA Class 40 RC2 -9/0 AKILARIA Class 40 RC3 -12/-3 ALAJUELA 33 198 ALAJUELA 38 216 ALBERG 29 225 ALBERG 30 228 ALBERG 35 201 ALBERG 37 YAWL 162 ALBIN 7.9 234 ALBIN BALLAD 30 186 ALBIN CUMULUS 189 ALBIN NIMBUS 42 99 ALBIN NOVA 33 159 ALBIN STRATUS 150 ALBIN VEGA 27 246 Alden 42 CARAVELLE 159 ALDEN 43 SD SM 120 ALDEN 44 111 ALDEN 44-2 105 ALDEN 45 87 ALDEN 46 84 ALDEN 54 57 ALDEN CHALLENGER 156 ALDEN DOLPHIN 126 ALDEN MALABAR JR 264 ALDEN PRISCILLA 228 ALDEN SEAGOER 141 ALDEN TRIANGLE 228 ALERION XPRS 20 *(U)* 249 ALERION XPRS 28 168 ALERION XPRS 28 WJ 180 ALERION XPRS 28-2 (150+) 165 ALERION XPRS 28-2 SD 171 ALERION XPRS 28-2 WJ 174 ALERION XPRS 33 120 ALERION XPRS 33 SD 132 ALERION XPRS 33 Sport 108 ALERION XPRS 38Y ODR 129 ALERION XPRS 38-2 111 ALERION XPRS 38-2 SD 117 ALERION 21 231 ALERION 41 99/111 ALLIED MISTRESS 39 186 ALLIED PRINCESS 36 210 ALLIED SEABREEZE 35 189 ALLIED SEAWIND 30 246 ALLIED SEAWIND 32 240 ALLIED XL2 42 138 ALLMAND 31 189 ALLMAND 35 156 ALOHA 10.4 162 ALOHA 30 144 ALOHA 32 171 ALOHA 34 162 ALOHA 8.5 198 AMEL SUPER MARAMU 120 AMEL SUPER MARAMU 2000 138 AMERICAN 17 *(U)* 216 AMERICAN 21 306 AMERICAN 26 288 AMF 2100 231 ANDREWS 26 144 ANDREWS 36 87 ANTRIM 27 87 APHRODITE 101 135 APHRODITE