Anselm Kiefer at the Met Breuer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jerusalem As Trauerarbeit on Two Paintings by Anselm Kiefer and Gerhard Richter

Jerusalem as Trauerarbeit 59 Chapter 3 Jerusalem as Trauerarbeit On Two Paintings by Anselm Kiefer and Gerhard Richter Wouter Weijers In 1986, Anselm Kiefer produced a painting he entitled Jerusalem (Fig. 3.1). It is a large and heavy work measuring approximately thirteen by eighteen feet. When viewed up close, the surface is reminiscent of abstract Matter Painting. Liquid lead was applied, left to solidify and then scraped off again in places, ripping the work’s skin. When the work is viewed from a distance, a high hori- zon with a golden glow shining over its centre appears, which, partly due to the title, could be interpreted as a reference to a heavenly Jerusalem. Two metal skis are attached to the surface, which, as Fremdkörper, do not enter into any kind of structural or visual relationship with the painting Eleven years later, Gerhard Richter painted a much smaller work that, although it was also given the title Jerusalem, was of a very different order (Fig. 3.2). The painting shows us a view of a sun-lit city. But again Jerusalem is hardly recognizable because Richter has let the city dissolve in a hazy atmo- sphere, which is, in effect, the result of a painting technique using a fine, dry brush in paint that has not yet completely dried. It is the title that identifies the city. Insiders might be able to recognize the western wall of the old city in the lit-up strip just below the horizon, but otherwise all of the buildings have dis- appeared in the haze. -

Anselm Kiefer Bibliography

G A G O S I A N Anselm Kiefer Bibliography Selected Books and Catalogues: 2020 Dermutz, Klaus. Anselm Kiefer: Superstrings, Runes, The Norns, Gordian Knot. London: White Cube. 2019 Adriani, Götz. Baselitz, Richter, Polke, Kiefer: The Early Years of the Old Masters. Dresden: Michel Sandstein. Cohn, Daniele. Anselm Kiefer: Studios. Paris: Flammarion. Trepesch, Christof. Anselm Kiefer aus der Sammlung Walter (Augsburg, Germany: Kunstmuseum Walter. Dermutz, Klaus. Anselm Kiefer in Conversation with Klaus Dermutz. London: Seagull Books. Granero, Natalia, Götz Adriani, Jean-Max Colard, Anselm Kiefer, Gunnar B. Kvaran and Rainer Michael Mason. Anselm Kiefer - Livres et xylographies. Montricher: Fondation Jan Michalski pour l’écriture et la littérature, Oslo: Astrup Fearnley Museet. Chauveau, Marc and Anselm Kiefer. Anselm Kiefer à La Tourette. Paris: Bernard Chauveau Édition; New York: Gagosian, English edition, 2020. Baume, Nicholas, Richard Calvocoressi and Anselm Kiefer. Uraeus. New York: Gagosian. 2018 Amadasi, Giovanna, Matthew Biro, Massimo Cacciari, Gabriele Guercio. Anselm Kiefer: The Seven Heavenly Palaces. Milano: Pirelli HangarBiccoca and Mousse Publishing. Bastian, Heiner. Anselm Kiefer: Bilder / Paintings. Munich: Schirmer/Mosel. Kiefer, Anselm. Anselm Kiefer: Für Andrea Emo. Pantin/Paris: Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac. 2017 Chevillot, Chaterine, Sophie Blass-Fabiani, Véronique Mattiussi, Sylvie Patry, and Hélène Marraud. Kiefer-Rodin. Paris: Editions Gallimard. Knausgaard, Karl Ove, James Lawrence and Louisa Buck. Anselm Kiefer: Transition from Cool to Warm. New York: Rizzoli & Gagosian. Czeczot, Ivan, Klaus Dermutz, Dimitri Ozerkov, Mikhail Piotrovsky, Peter Sloterdijk. Anselm Kiefer: For Velimir Khlebnikov, Fates of Nations. St. Petersburg: The State Hermitage Museum. Stonard, Jean-Paul. Anselm Kiefer: Walhalla. London: White Cube. Clearwater, Bonnie, Norman Rosenthal and Joseph Thompson. -

ANSELM KIEFER | BOOKS and WOODCUTS 8 February to 12 May 2019

PRESS RELEASE Exhibition at the Jan Michalski Foundation for Writing and Literature: ANSELM KIEFER | BOOKS AND WOODCUTS 8 February to 12 May 2019 The German artist Anselm Kiefer (*1945, Donaueschingen) long hesitated between two practices, writing and painting. Although it was the latter he eventually chose, literature continues to play a preponderant role in his body of work. Through their materiality and esthetic, books were the first support for his artmaking, and writing every day in a journal has enabled the artist to reflect on his work and to engage in research that is closely connected with his thinking. In his early book production, which he began in 1968-1969, Anselm Kiefer was sizing up certain schools of art like De Stijl, Suprematism, and Minimalism. At the same time he continued with his work on German history and culture as an antidote to the trauma experienced by his and subsequent generations after the Second World War but also, more simply, as an artistic exploration of himself and his roots. Photography is often seen in the early books, but these already show the growing prevalence of drawing and watercolour, along with the appearance of materials like sand, pages clipped from magazines, hair, dried flowers, and miscellaneous objects. These unwritten volumes are designed like artist’s books, single copies, and serve at first as a place where Anselm Kiefer expressed ideas, associations and thoughts, the subsequent tomes quickly became a place for exploration in which the succession of pages made it possible to construct a narrative and situate it in time. The subjects elaborated there were then rescaled within the body of work as a whole, notably in his output of woodcuts. -

Annual Report 2010 Kröller-Müller Museum Introduction Mission and History Foreword Board of Trustees Mission and Historical Perspective

Annual report 2010 Kröller-Müller Museum Introduction Mission and history Foreword Board of Trustees Mission and historical perspective The Kröller-Müller Museum is a museum for the visual arts in the midst of peace, space and nature. When the museum opened its doors in 1938 its success was based upon the high quality of three factors: visual art, architecture and nature. This combination continues to define its unique character today. It is of essential importance for the museum’s future that we continue to make connections between these three elements. The museum offers visitors the opportunity to come eye-to-eye with works of art and to concentrate on the non-material side of existence. Its paradise-like setting and famous collection offer an escape from the hectic nature of daily life, while its displays and exhibitions promote an awareness of visual art’s importance in modern society. The collection has a history of almost a hundred years. The museum’s founders, Helene and Anton Kröller-Müller, were convinced early on that the collection should have an idealistic purpose and should be accessible to the public. Helene Kröller-Müller, advised by the writer and educator H.P. Bremmer and later by the entrance Kröller-Müller Museum architect and designer Henry van de Velde, cultivated an understanding of the abstract, ‘idealistic’ tendencies of the art of her time by exhibiting historical and contemporary art together. Whereas she emphasised the development of painting, in building a post-war collection, her successors have focussed upon sculpture and three-dimensional works, centred on the sculpture garden. -

ANSELM KIEFER Education Solo Exhibitions

ANSELM KIEFER 1945 Born in Donaueschingen, Germany Lives and works in France Education 1970 Staatliche Kunstakademie, Düsseldorf, Germany 1969 Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Karlsruhe, Germany Solo exhibitions 2021 Field of the Cloth of Gold, Gagosian Le Bourget, France 2020 Permanent Public Commission, Panthéon, Paris Für Walther Von Der Vogelweide, Thaddaeus Ropac, Salzburg Villa Kast, Austria Opus Magnum, Franz Marc Museum, Kochel, Germany Superstrings, Runes, the Norns, Gordian Knot, White Cube, London 2019 Couvent de la Tourette, Lyon, France Books and Woodcuts, Foundation Jan Michalski, Montricher, Switzerland; Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo 2018 ARTISTS ROOMS: Anselm Kiefer, Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, West Midlands, UK Fugit Amor, Lia Rumma Gallery, Naples For Vicente Huidobro, White Cube, London Für Andrea Emo, Galerie Thaddeus Ropac, Paris Uraeus, Rockefeller Center, New York 2017 Provocations: Anselm Kiefer at the Met Breuer, Met Breuer, New York Anselm Kiefer, for Velimir Khlebnikov, The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia Transition from Cool to Warm, Gagosian, New York For Louis-Ferdinand Céline: Voyage au bout de la nuit, Copenhagen Contemporary, Denmark Kiefer Rodin, Rodin Museum, Paris; Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 2016 The Margulies Collection at the Warehouse, Miami Walhalla, White Cube, London The Woodcuts, Albertina Museum, Vienna Regeneration Series: Anselm Kiefer from the Hall Collection, NSU Art Museum, Fort Lauderdale, Florida 2015 Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris In the -

Gesamt- Kunstwerk —An Icon on the Move— Madeleine Steigenga

Gesamt- kunstwerk —An Icon on the Move— Madeleine Steigenga Edited by 4 members 100 In 1996, I called Martin and Joke Visser to ask whether our office would be allowed to visit their Rietveld House renovated by Van Eyck. I studied in Eindhoven for almost ten years without visiting it. Van Eyck played an important role during my studies. Angered by the appointment of our final year profes- sor Dick Apon – one of his Forum friends – Van Eyck then avoided any contact with this alternative architecture course at the TU/e. And Rietveld – having died not too long be- fore – was given little attention in those days. The architects who did play a part in this period and promoted their work in Eindhoven, were Eisenman, Koolhaas, Hertzberger and Krier. We travelled through both Europe and the USA, but I did not go to the little town of Bergeijk for its architecture, but for the De Ploeg fabric remainder sale in Rietveld’s building. So, twenty years after my leaving Eindhoven, that is why I paid a visit to this work by Rietveld and Van Eyck. What did I know about the client and the inha- bitants Martin and Joke Visser, about their designs and their art collection? During my studies, one of Panamarenko’s aeroplanes was bought by the univer- sity art committee; Visser had mediated the deal. He occasionally took a class with his first wife Mia in a series by Wim Quist. And I naturally knew about his furniture. His se43 dining-room chairs upholstered in pulp cane stood round the meeting table in my dad’s study at university. -

L'onde Du Midi, Elias Crespin © Elias Crespin

PRESS RELEASE Contemporary Art From January 25, 2020 Sully wing, level 1, Escalier du Midi Elias Crespin L’Onde du Midi A new permanent installation for the Louvre To mark the 30th anniversary of the Pyramid, the Musée du Louvre has commissioned another major public artwork, inviting Venezuelan contemporary artist Elias Crespin to design a new permanent piece for the museum. Consisting of 128 metal tubes hanging from motor-powered cables, the artist’s kinetic creation, L’Onde du Midi, will perform its subtle choreography at the top of the Escalier du Midi in the southeast corner of the Cour Carrée. Crespin thus follows in the footsteps of leading contemporary art figures who have created works for the Louvre, such as Anselm Kiefer (2007), François Morellet (2010) and Cy Twombly (2010). L’Onde du Midi An example from the artist’s “Plano Flexionante” series, the sculpture is made up of parallel rows of 128 cylindrical tubes suspended in mid- This artwork enjoys the support of the air by invisible cables. When still, the ethereal mobile becomes a ARTEXPLORA endowment fund rectangular horizontal plane some 10 meters in length (W. 1.50 x L. 9.5 m). In perpetual motion, the piece seems unaffected by gravity, moving L’Onde du Midi—Key Figures: through space at a height of 3 to 4.5 meters in sequences regulated by numerical algorithms. This non-linear, undulating mechanical dance - 128 aluminum tubes invites visitors to slow down and contemplate the enchanting work. - 256 motors - Sequence duration: around 30 minutes As though hypnotized, the spectator is drawn into the slow, graceful interplay of shapes, with its unexpected and infinite variations. -

Cy Twombly: Third Contemporary Artist Invited to Install a Permanent Work at the Louvre Artdaily March

Artdaily.org March 24, 2010 GAGOSIAN GALLERY Cy Twombly: Third Contemporary Artist Invited to Install a Permanent Work at the Louvre View of the The Louvre's large new gallery ceiling by Cy Twombly, known for his abstract paintings only the third contemporary artist given the honor of designing a permanent work for the museum, in Paris, Tuesday, March 23, 2010. (AP Photo/Christophe Ena.) PARIS.- Selected by a committee of international experts, Cy Twombly is the third contemporary artist invited to install a permanent work at the Louvre: a painted ceiling for the Salle des Bronzes. The permanent installation of 21st century works at the Louvre, the introduction of new elements in the décor and architecture of the palace, is the cornerstone of the museum’s policy relating to contemporary art. This type of ambitious endeavor is in keeping with the history of the palace, which has served since its creation as an ideal architectural canvas for commissions of painted and sculpted decoration projects. Prior to Cy Twombly, the Louvre’s commitment to living artists has resulted in invitations extended to Anselm Kiefer in 2007 and to François Morellet for an installation unveiled earlier in 2010, but these three artists also follow in the footsteps of a long line of predecessors including Le Brun, Delacroix, Ingres and, in the twentieth century, Georges Braque. Twombly’s painting will be showcased on the ceiling of one of the Louvre’s largest galleries, in one of the oldest sections of the museum. It is a work of monumental proportions, covering more than 350 square meters, its colossal size ably served by the painter’s breathtaking and unprecedented vision. -

THE UNFINISHABLE BUSINESS of SOUTH AFRICA in the WORK of HANS HAACKE . by Ntongela Masilela More Than Any Other Artist of Our Ti

Untitled Document THE UNFINISHABLE BUSINESS OF SOUTH AFRICA IN THE WORK OF HANS HAACKE . by Ntongela Masilela More than any other artist of our time, Hans Haacke has wrought a visual equivalent of Walter Benjamin's observation that 'there is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.' - Yve-Alain Bois, "The Antidote", October (1986). Haacke ist sich bewusst, dass alle gesellschaftlichen Handlungen, einschliesslich der Kunst, explizit oder implizit politischer Natur sind. - Edward F. Fry, "Hans Haacke", Documenta 8 (Katalog), 1987. Haacke's work seems to me to emerge at this point, as a solution to certain crucial dilemmas of a left cultural politics based on this heightened awareness of the role of the institutions. - Fredric Jameson, "Hans Haacke and the Cultural Logic of Postmodernism", Hans Haacke: Unfinished Business (ed.), Brian Wallis, 1987. The most fascinating artists to this observer at last year's Documenta 8 (1987) exhibition in Kassel , West Germany were Mark Tansey, Hans Haacke and Fabrizio Plessi: an American, a German-America and an Italian. Their art work stood out in preeminence in an exhibition that included work from some of the outstanding artists of our time: Anselm Kiefer, the late Joseph Beuys, Richard Serra, Aldo Rossi, Arata Isozaki, and others. The last two-named, architects, make plain why it has been in the field of architecture that epoch-making battles, those that define processes of periodization, on the theories of postmodernism and postmodernity have been bitterlt -

Anselm Kiefer Biography

G A G O S I A N Anselm Kiefer Biography Born in 1945 in Donaueschingen, Germany. Lived and worked 1971–1993 in Hornbach, Buchen and Höpfingen, Germany. Lived and worked 1993–2007 in Barjac, France. Since 2007 lives and works in Barjac, Croissy and Paris, France. Selected Solo Exhibitions: 2021 Anselm Kiefer: Field of the Cloth of Gold. Gagosian, Le Bourget, Paris, France. 2020 Anselm Kiefer: Fur Walther von der Vogelweide. Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London, England. Anselm Kiefer. Opus Magnum. Franz Marc Museum, Kochel am See, Germany. 2019 Anselm Kiefer. Voorlinden, Wassenaar, Netherlands. Anselm Kiefer: Superstrings, Runes, The Norns, Gordian Knot. White Cube, Bermondsey, London, England. Anselm Kiefer à La Tourette. Couvent de La Tourette, Éveux, France. Anselm Kiefer: Bøker og tresnitt. Astrup Fearnley Museum, Oslo, Norway. Anselm Kiefer: Livres et xylographies. Fondation Jan Michalski, Montricher, Switzerland. Anselm Kiefer aus der Sammlung Walter. Kunstmuseum Walter, Augsbeurg, Germany. 2018 Artist Rooms: Anselm Kiefer. Herbert Art Gallery & Museum, Coventry, England. Anselm Kiefer: Uraeus. Rockefeller Center, New York, NY. Anselm Kiefer: Lebenszeit – Weltzeit. Galerie Bastian, Berlin, Germany. Anselm Kiefer: Fuigit Amor. Galleria Lia Rumma, Naples, Italy. For Vicente Huidobro. White Cube, London, England. Für Andrea Emo. Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, Paris Pantin, France. 2017 Provocations: Anselm Kiefer at the Met Breuer. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY. Anselm Kiefer: Bilder. Galerie Bastian, Berlin, Germany. Kiefer Rodin. Musée Rodin, Paris, France; traveled to the Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, PA. Anselm Kiefer: For Louis-Ferdinand Céline: Voyage au bout de la nuit . Copenhagen Contemporary, Copenhagen, Denmark. Anselm Kiefer. Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, Germany. Anselm Kiefer: Transition from Cool to Warm. -

"New Contemporary Art Decor Signed Elias Crespin Soon at the Louvre," Knowledge Of

New contemporary art decor signed Elias Crespin soon at the Louvre | Knowledge of the Arts 12/17/2019 New contemporary art decor signed Elias Crespin soon at the Louvre Elias Crespin, Simulation of L'Onde du Midi (detail) © Elias Crespin Visual Pascal Maillard From January 25, an electrokinetic sculpture by Elias Crespin will be installed on the rst oor of the Midi staircase (Sully wing) of the Louvre museum. After Anselm Kiefer, François Morellet and Cy Twombly, it's Elias Crespin's turn to endow the Louvre with one of his works. On the occasion of the thirtieth anniversary of the Pyramid, the museum invites the contemporary Venezuelan artist for a new lasting decoration. Entitled Onde du Midi, the work will be located at the top of the Midi staircase, at the southeast corner of the Cour Carrée (Sully wing), offering visitors “a stopover in its journey, becoming the theater of 'a silent ballet,' explains the museum. A silent ballet Like the artist's other creations, the Onde du Midi combines science and art. The sculpture will be made up of 128 cylindrical metal tubes suspended from invisible wires animated by 256 motors which will draw a wave choreography over a 30-minute sequence. L' Onde du Midi will be almost 10 meters long and will be in constant motion to the rhythm of the digital algorithms developed by the artist, a computer engineer by training. New contemporary art decor signed Elias Crespin soon at the Louvre | Knowledge of the Arts This kinetic work belongs to the category of mobiles “Plano Flexionante” by Elias Crespin which create surprising spatial configurations. -

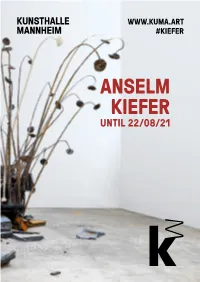

ANSELM KIEFER UNTIL 22/08/21 PROGRAM LEVEL At: Found Be Can Show the with Conjunction in Program Entire the Art

WWW.KUMA.ART #KIEFER ANSELM KIEFER UNTIL 22/08/21 LEVEL HECTOR-BAU JUGENDSTIL-BAU EXHIBITION ROOM 1 ROOM 2 ROOM 3 THE GREAT IN THE HORTUS CARGO BEGINNING CONCLUSUS MULLEIN WOMEN OF PALM ATRIUM ANTIQUITY SUNDAY LILITH 20 YEARS BLACK PASSAGE MUTATULI OF FLAKES SATURN TIME SOLITUDE ENTRANCE SHEBIRAT HA KELIM CENSUS (LEVIATHAN) LUXX SEPHIROT The exhibition is accompanied by Visitors also have the opportunity an extensive supporting program. to engage with Kiefer’s oeuvre CUBE CUBE CUBE THE FERTILE 5 6 7 CRESCENT In several lectures in coopera- by attending readings, concerts, tion with the Jewish Community guided tours and artist’s talks. in Mannheim, among others, the One of the highlights of the suppor- Kunsthalle sheds light on the ting program is the symposium intercultural context of Kiefer’s “Concepts and Material in Anselm art. Kiefer’s Art” in spring of 2021. THE LOST The entire program in conjunction with the show can be found at: LETTER WWW.KUMA.ART/ANGEBOTE JAIPUR LEVEL DATES AND SPECIALS AT: WWW.KUMA.ART PROGRAM Anselm Kiefer is one of the most fa- change in direction of the Cold War and sculptures result in either The exhibition displaying large- mous contemporary German artists. and the demise of the Soviet Union, entirely abstract or figurative com- format, multidimensional pictures In his work which is characterized Kiefer turns against the “end of positions. Kiefer’s works are con- and sculptures focuses on three by heavy materiality, he engages history” and literally incorporates the temporary history paintings that important work phases, from early with existential issues.