Navigation for a Sustainable Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overview of Chiller Compressors

Overview of Chiller Compressors Course No: M04-027 Credit: 4 PDH A. Bhatia Continuing Education and Development, Inc. 22 Stonewall Court Woodcliff Lake, NJ 07677 P: (877) 322-5800 [email protected] OVERVIEW OF CHILLER COMPRESSORS Overview In HVAC industry, the refrigeration machine that produces chilled water is referred to as a “Chiller”. A chiller package operates either on the principles of vapor compression or vapor absorption. The vapor compression system uses mechanical energy in the form of electric motor to drive the cooling cycle whereas absorption chillers use heat to drive the process. The vapor compression chiller system, which is far more prominent in commercial buildings, consists of four major components: the compressor, evaporator, condenser and expansion device all packaged as a single unit. The classification of vapor compression chiller packages is generally by the type of compressor: centrifugal, reciprocating, and screw being the major ones. Chillers are the largest consumer of energy in a commercial building and it is therefore important to understand the relative benefits and limitations of various types in order to make the right economic decisions in chiller installation and operation. This course will talk about the type of compressor used in the water cooled chiller. The course is divided into 3 parts: Part - I: Types of Chiller Compressors Part – II: Comparison of Chiller Compressors Part –III: Economic Evaluation of Chiller Systems PART I - TYPES OF CHILLER COMPRESSORS Most cooling systems, from residential air conditioners to large commercial and industrial chillers, employ the refrigeration process known as the vapor compression cycle. At the heart of the vapor compression cycle is the mechanical compressor. -

Rental Cooling Guide for Tents & Shelters

Rental Cooling Guide For Tents & Shelters Taking you a step closer to cool Let’s get down to business. You’ve got a hot spot and you need cooling. It’s not everyday you need to purchase air conditioning. How do you fig- ure out how much cooling you need? Where do you turn for help? This cooling load calculator will be your guide to help you determine what kind of cooling you need and how much cooling you need. We outline the questions you need to answer before you make the call to get some extra cooling. Know what you need and you’ll be a more knowledgeable pros- pect, certain to make a more informed buying decision. Determining Your Cooling Load is a simple three step process. Apply the basic rule of thumb for tent cooling — one ton of cooling, 12,000 BTU, for every 100 s.f. to 150 s.f. This method will give you a cooling range for the size tent you select. For example: a 60’ x 80’ tent is 4800 s.f. Divide the total s.f. by 150 and you will have the low end: 4800 / 150 = 32 tons. Divide the total s.f. by 100 and you will have the high end: 4800 / 100 = 48 tons. For a 60’ x 80’ tent you will need between 32 and 48 tons of cooling. AirPac Rents Your online source for portable air conditioner rentals 888-324-7722 www.AirPacRents.com Copyright © 2005 AirPac Rents, Incorporated. All rights reserved. 1 The amount of cooling you select will depend on the event itself. -

Guide for Air Conditioning, Refrigeration, and Help the Student

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 251 645 CE 040 232 AUTHOR Henderson, William Edward, Jr., Ed. TITLE Art::culated, Performance-Based Instruction Objectives Guide for Air Conditioning, Refrigeration, and Heating. Volume II(Second Year). INSTITUTION Greenville County School District, Greenville, S.C.; Greenville Technical Coll., S. PUB DATE Oct 84 NOTE 374p.; Prepared by the Articulation Program Task Force Committee for Air Conditioning, Refrigeration, and Heating. PUB TYPE Guides Clasrroom Use Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTO. *Air Conditioning; Behavioral Objectives; Competency Based Education; Curriculum Guides; *Equipment Maintenance; Fuels; Jrade 12; *Heating; High Schools; Job Skills; Le.,zning Activities; *Refrigeration; Secondary Education; Solar Energy; Trade and Industrial Education; Units of Study; *Ventilation ABSTRACT This articulation guide contains 17 units of instruction for the second year of a two-year vocational program designed to prepare the high school graduate to install, maintain, and repair various types of residential and commercial heating, air conditioning, and refrigeration equipment. The units are designed to help the student to expand and apply the basic knowledge already mastered and to learn new principles and techniques and to prepare him/her for entry-level work as an apprentice. The seventeen units cover aid conditioning calculations (psychrometrics,residential heat loss and heat gain, duct design and sizing and air treatment); troubleshooting and servicing residential air conditioners; commercial refrigeration; commercial air conditioning; heating systems (electrical resistance heating, heat pumps, gas heating, oil heating, hydronics, solar heating systems); automotive air conditioner maintenance/repair; estimating and planning heating, ventilation, and air conditioning jobs; customer relations; and shop projects. -

Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Chronology

Air Conditioning and Refrigeration C H R O N O L O G Y Significant dates pertaining to Air Conditioning and Refrigeration revised May 4, 2006 Assembled by Bernard Nagengast for American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air Conditioning Engineers Additions by Gerald Groff, Dr.-Ing. Wolf Eberhard Kraus and International Institute of Refrigeration End of 3rd. Century B.C. Philon of Byzantium invented an apparatus for measuring temperature. 1550 Doctor, Blas Villafranca, mentioned process for cooling wine and water by adding potassium nitrate About 1597 Galileo’s ‘air thermoscope’ Beginning of 17th Century Francis Bacon gave several formulae for refrigeration mixtures 1624 The word thermometer first appears in literature in a book by J. Leurechon, La Recreation Mathematique 1631 Rey proposed a liquid thermometer (water) Mid 17th Century Alcohol thermometers were known in Florence 1657 The Accademia del Cimento, in Florence, used refrigerant mixtures in scientific research, as did Robert Boyle, in 1662 1662 Robert Boyle established the law linking pressure and volume of a gas a a constant temperature; this was verified experimentally by Mariotte in 1676 1665 Detailed publication by Robert Boyle with many fundamentals on the production of low temperatures. 1685 Philippe Lahire obtained ice in a phial by enveloping it in ammonium nitrate 1697 G.E. Stahl introduced the notion of “phlogiston.” This was replaced by Lavoisier, by the “calorie.” 1702 Guillaume Amontons improved the air thermometer; foresaw the existence of an absolute zero of temperature 1715 Gabriel Daniel Fahrenheit developed mercury thermoneter 1730 Reamur introduced his scale on an alcohol thermometer 1742 Anders Celsius developed Centigrade Temperature Scale, later renamed Celsius Temperature Scale 1748 G. -

![[ -- Power Knot LLC. What Is a Ton of Refrigeration?. 2010-03-06 -- ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6139/power-knot-llc-what-is-a-ton-of-refrigeration-2010-03-06-1296139.webp)

[ -- Power Knot LLC. What Is a Ton of Refrigeration?. 2010-03-06 -- ]

Power Knot LLC 501 Valley Way Milpitas CA 95035 USA What is a ton of refrigeration? +1-408-587-9333 www.powerknot.com 2010-03-06 Commercial refrigeration systems in the US are mostly rated in tons of refrigeration and this term is used widely in other parts of the world. However, outside the US, cooling systems may be normally specified in kW (or MW) or in Btu/h. The roots for refrigeration are in the ice making industry, and the ice manufacturers wanted an easy way of understanding the size of a refrigeration system in terms of the production of ice. If 288,000 Btu are required to make one ton of ice, divide this by 24 hours to get 12,000 Btu/h required to make one ton of ice in one day. This is the requirement for the phase change from liquid to solid — to convert water at 0°C (+32°F) into ice at 0°C (+32°F). As a practical matter, additional refrigeration is required to take water at room temperature and turn it into ice. To be specific, one ton of refrigeration capacity can freeze one short ton of water at 0°C (32°F) in 24 hours. So, a ton of refrigeration is 3.517 kW. This is derived as follows: The latent heat of ice (also the heat of fusion) = 333.55 kJ/kg = 144 Btu/lb One short ton = 2000 lb Heat extracted = 2000 x 144/24 hr = 288000 Btu/24 hr = 12000 Btu/hr = 200 Btu/min 1 ton refrigeration = 200 Btu/min = 3.517 kJ/s = 3.517 kW = 4.713 HP A much less common definition is: 1 tonne of refrigeration is the rate of heat removal required to freeze a metric ton (1000 kg) of water at 0°C in 24 hours. -

Fundamentals of Refrigeration 3.1

Fundamentals of Refrigeration of Fundamentals Fundamentals of Refrigeration Changing the way you think about refrigeration LI 001 V3 001 LI ™® The following are tradenames or registered trademarks of their respective companies: BACnet from ASHRAE; Mod- bus from Schneider Electric Ltd; MicroTech III, Open Choices, from Daikin Applied; LONMARK, LonTalk, and LONWORKS are managed, granted and used by LONMARK International under a license granted by Echelon Corporation. 800.432.1342 ©2016 Daikin Applied www.DaikinApplied.com LI 001 (06/16) 001_Refrigeration_Cover_Wrap.indd All Pages 5/27/2016 12:33:11 PM Fundamentals of Refrigeration 3.1 Refrigeration Cycles 3 A refrigeration system moves heat from a space, fluid or material for the purpose of lowering its temperature. In the past, this was done by collecting ice in the winter and using its specific heat to cool as the ice melted. When 1 pound of ice melts, it absorbs 144 Btu, as latent energy. When 1 ton (2000 lbs) melts over a 24-hour period: Q = 2000 lbs × 144 Btu/lb/24 hrs = 12,000 Btu/h This is the definition of 1 ton of refrigeration. Ideal Basic Refrigeration Cycle The ideal basic refrigeration cycle consists of four components, connected by piping with refrigerant flowing through the system. Figure 13 shows the components in the cycle and Figure 14 shows the basic cycle on the Ph diagram. 1 ton of cooling is the effect of 1 ton of ice melting over a 24 hour period. 4 CONDENSER 3 COMPRESSOR EXPANSION DEVICE 2 EVAPORATOR 1 Figure 13 Basic Refrigeration Cycle The evaporator is between points 1 and 2. -

Ecoenergetic Comparison of HVAC Systems in Data Centers

climate Article Ecoenergetic Comparison of HVAC Systems in Data Centers Alexandre F. Santos 1,2, Pedro D. Gaspar 1,3,* and Heraldo J. L. de Souza 2 1 Department of Electromechanical Engineering, University of Beira Interior, 6201-001 Covilhã, Portugal; [email protected] 2 FAPRO—Professional College, 80230-040 Curitiba, Brazil; [email protected] 3 C-MAST—Centre for Mechanical and Aerospace Science and Technologies, 6201-001 Covilhã, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-275-329-759 Abstract: The topic of sustainability is of high importance today. Global efforts such as the Montreal Protocol (1987) and the Kigali Amendment (2016) are examples of joint work by countries to reduce environmental impacts and improve the level of the ozone layer, the choice of refrigerants and air conditioning systems, which is essential for this purpose. But what indicators are to be used to measure something so necessary? In this article, the types of air conditioning and GWP (Global Warming Potential) levels of equipment in the project phase were discussed, the issue of TEWI (Total Equivalent Warming Impact) that measures the direct and indirect environmental impacts of refrigeration equipment and air conditioning and a new methodology for the indicator was developed, the TEWI DC (DC is the direct application for Data Center), and using the formulas of this new adapted indicator it was demonstrated that the TEWI DC for Chicago (USA) was 2,784,102,640 kg CO2/10 years and Curitiba (Brazil) is 1,252,409,640 kg CO2/10 years. This difference in value corresponds to 222.30% higher annual emissions in Chicago than in Curitiba, showing that it is much more advantageous to install a Data Center in Curitiba than in Chicago in terms of environmental impact. -

How to Convert HVAC Tons to Amps How to Calculate BTU Hours to KW How to Calculate BTU Requirement

How to Convert HVAC Tons to Amps In the heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) industry, tons are used as a way to measure an air conditioner's cooling capacity. In particular, one HVAC ton is equivalent to 12,000 BTUs per hour. One BTU refers to the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of 1 lb. of water by 1 degree Fahrenheit. To convert tons to amps, you must first convert tons to BTUs per hour, after which you can convert this value to watts, then use the formula amps = watts / volts to solve for amps. Instructions 1. Convert tons to BTUs per hour by multiplying it by 12,000. Given an air conditioner with 2 tons of cooling power, for instance, multiply two by 12,000 to get 24,000 BTUs / hour. 2. Multiply BTUs / hour by .293 to convert it to watts. Given the example, multiply 24,000 by .293 to obtain 7032 watts. 3. Divide watts by the given voltage value. Air conditioners in the United States operate on 120 volts, so given the example, divide 7032 watts by 120 volts to obtain a final answer of 58.6 amps. How to Calculate BTU Hours to KW BTU stands for a British thermal unit, which is the amount of energy required to raise one pound of water one degree Fahrenheit. BTUs per hour is a unit used to measure energy use, particularly in air conditioning and heating measurements. You can convert to BTU/hour from other units of energy such as watts, horsepower and tons. -

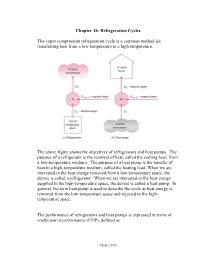

Chapter 10: Refrigeration Cycles

Chapter 10: Refrigeration Cycles The vapor compression refrigeration cycle is a common method for transferring heat from a low temperature to a high temperature. The above figure shows the objectives of refrigerators and heat pumps. The purpose of a refrigerator is the removal of heat, called the cooling load, from a low-temperature medium. The purpose of a heat pump is the transfer of heat to a high-temperature medium, called the heating load. When we are interested in the heat energy removed from a low-temperature space, the device is called a refrigerator. When we are interested in the heat energy supplied to the high-temperature space, the device is called a heat pump. In general, the term heat pump is used to describe the cycle as heat energy is removed from the low-temperature space and rejected to the high- temperature space. The performance of refrigerators and heat pumps is expressed in terms of coefficient of performance (COP), defined as Chapter 10-1 Desired output Cooling effect QL COPR === Required input Work input Wnet, in Desired output Heating effect QH COPHP === Required input Work input Wnet, in Both COPR and COPHP can be larger than 1. Under the same operating conditions, the COPs are related by COPHP=+ COP R 1 Can you show this to be true? Refrigerators, air conditioners, and heat pumps are rated with a SEER number or seasonal adjusted energy efficiency ratio. The SEER is defined as the Btu/hr of heat transferred per watt of work energy input. The Btu is the British thermal unit and is equivalent to 778 ft-lbf of work (1 W = 3.4122 Btu/hr). -

UNIT-6 Refrigeration

www.getmyuni.com UNIT-6 Refrigeration Definition Refrigeration is the process of providing and maintaining temperature of the system below that of the surrounding atmosphere. Carnot Cycle The reversed carnot cycle can be considered in refrigeration system. T2 COP..= where TT2< 1 TT2− 1 Unit of Refrigeration The common unit used in the field of refrigeration is known as Ton of refrigeration. A ton of refrigeration is defined as the quantity of heat required to be removed to produce one ton (1000kg) of ice within 24 hours when the initial condition of water is 0ºC 1000x 335 Ton of refrigeration = = 3.5 kJ/s 24x3600 Consider a refrigerator of T tons capacity, Refrigeration capacity = 3.5 kJ/s Heat removed from refrigerator = Refrigeration effect =R.E. kJ/s Power of the compressor =work/kg of refrigerant x mass flow rate Air Refrigeration system working on Bell-coleman cycle In air refrigeration system, air is used as the refrigerant which always remains in the gaseous phase. The heat removed consists only of sensible heat and as a result, the coefficient of performance (C.O.P) is low. The various processes are: 1 www.getmyuni.com Process 1-2: The air leaving the evaporator enters a compressor. Where it is compressed isentropically to higher pressure and temperature. Process 2-3: This high pressure, high temperature air, then enters a cooler where it is cooled at constant pressure to a low temperature. Process 3-4: This high pressure, low temperature air is then expanded in an expander to lower pressure and temperature in a isentropic manner.At point 4, the temperature of the air will be lowest. -

Design of a Small-Scale, Low-Cost Cold Storage System

Design of a Small-Scale, Low-Cost Cold Storage System Local Roots Team Members: Robert Kraemer, Andrew Plouff, John Venn BE 487: Biosystems Design Project Executive Summary Dr. John Biernbaum plans to add an energy efficient cold storage unit to the Student Organic Farm (SOF). The Local Roots team was tasked with designing the cold storage unit. Efficient cold storage enables farmers to provide pristine produce year round to purchasers at a low energy cost. Proper cooling and storage of produce is as essential to a farm’s success as growing quality produce is. The Local Roots team was provided with the storage loads, and was asked to design an aboveground and a basement cold storage unit. Using the maximum produce load of 32,250 lbs, and the storage containers required to accommodate the load, the dimensions of the room were determined. The range of produce can be stored using two different room conditions. One room will be cool and dry with a temperature range between 50-60 F and 60-70% relative humidity. The other room will be cold and damp with a range of 36-40 F and 85-95% relative humidity. The dimensions of the large room were calculated to be 35ft x 25ft and the small room is 21ft x 17ft. Each room is 8 ft tall. Instead of having two equal sized rooms, it was determined to be more efficient to have a large room and a small room, switching which room would have the cool or cold produce depending on the season. The large room would store the cold produce in summer and the cool produce in winter. -

HVAC Cooling Systems for Data Centers

HVAC Cooling Systems for Data Centers Course No: M05-020 Credit: 5 PDH A. Bhatia Continuing Education and Development, Inc. 22 Stonewall Court Woodcliff Lake, NJ 076 77 P: (877) 322-5800 [email protected] HVAC COOLING SYSTEMS FOR DATA CENTERS Abstract Air-conditioning systems for data centers are designed for year-round cooling with very high cooling intensity per square foot of floor area. The high sensitivity of electronic components in such facilities requires that temperature, humidity, air movement and air cleanliness must be kept consistent and within specific limits to prevent premature equipment failures and costly downtime. Because data centers are high-density enclosed spaces that generate a significant amount of heat, traditional comfort cooling systems can't remove enough heat to protect the critical equipment. Instead, these unique areas require dedicated units with precision cooling capabilities. In a typical data center environment for example; the heat densities can be up to five times higher than in a typical office setting. To illustrate, one ton of comfort cooling capacity (12,000 BTU/hour, or 3,517 W) is required per 250 to 300 square feet of office space. This translates into 12 to 14 watts per square foot. In contrast, one ton of precision cooling capacity is required per 50 to 100 square feet of data center space, which translates to 35 to 70 watts per square foot on average. New data centers today have load densities as high as 200 to 300 watts per square foot. From an airflow standpoint, precision cooling equipment typically supply between 500 and 900 cubic feet per minute (CFM) per cooling ton.