Meddling with 'Hifalut'n Foolishness': Capturing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

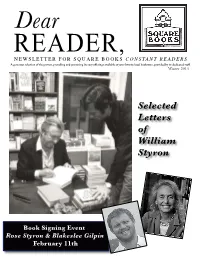

Selected Letters of William Styron

Dear Winter 2013 Selected Letters of William Styron Book Signing Event Rose Styron & Blakeslee Gilpin February 11th THE YEAR IN REVIEW 2012 With 2012 in rear view, we are very thankful for the many writers who came to us and the publishers who sent them to Square Books, as their books tend to dominate our bestseller list; some, like James Meek (The Heart Broke In, #30) and Lawrence Norfolk (John Saturnall’s Feast, #29), from as far as England – perhaps it’s the fascination with Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey (67) or J. K. Rowling’s Casual Vacancy (78). But as Dear Readers know, this list is usually crowded with those who live or have lived here, like Dean Wells’ Every Day by the Sun (22) or (long ago) James Meredith (A Mission From God, (10); William Faulkner’s Selected Stories (43), Ole Miss at Oxford, by Bill Morris (37), Mike Stewart’s Sporting Dogs and Retriever Training (39), John Brandon’s A Million Heavens (24), Airships (94), by Barry Hannah, Dream Cabinet by Ann Fisher-Wirth (87), Beginnings & Endings (85) by Ron Borne, Facing the Music (65) by Larry Brown, Neil White’s In the Sanctuary of Outcasts (35), the King twins’ Y’all Twins? (12), Tom Franklin’s Crooked Letter Crooked Letter (13), The Fall of the House of Zeus (15) by Curtis Wilkie, Julie Cantrell’s Into the Free (16), Ole Miss Daily Devotions (18), and two perennial local favorites Wyatt Waters’ Oxford Sketchbook (36) and Square Table (8), which has been in our top ten ever since it was published; not to forget Sam Haskell and Promises I Made My Mother (6) or John Grisham, secure in the top two spots with The Racketeer and Calico Joe, nor our friend Richard Ford, with his great novel, Canada (5). -

The Graphic Novel and the Age of Transition: a Survey and Analysis

The Graphic Novel and the Age of Transition: A Survey and Analysis STEPHEN E. TABACHNICK University of Memphis OWING TO A LARGE NUMBER of excellent adaptations, it is now possible to read and to teach a good deal ot the Transition period litera- ture with the aid of graphic, or comic book, novels. The graphic novei is an extended comic book, written by adults for adults, which treats important content in a serious artistic way and makes use of high- quality paper and production techniques not available to the creators of the Sunday comics and traditional comic books. This flourishing new genre can be traced to Belgian artist Frans Masereel's wordless wood- cut novel. Passionate Journey (1919), but the form really took off in the 1960s and 1970s when creators in a number of countries began to employ both words and pictures. Despite the fictional implication of graphic "novel," the genre does not limit itself to fiction and includes numerous works of autobiography, biography, travel, history, reportage and even poetry, including a brilliant parody of T. S. Eliot's Waste Land by Martin Rowson (New York: Harper and Row, 1990) which perfectly captures the spirit of the original. However, most of the adaptations of 1880-1920 British literature that have been published to date (and of which I am aware) have been limited to fiction, and because of space considerations, only some of them can be examined bere. In addition to works now in print, I will include a few out-of-print graphic novel adap- tations of 1880-1920 literature hecause they are particularly interest- ing and hopefully may return to print one day, since graphic novels, like traditional comics, go in and out of print with alarming frequency. -

List of Publishers' Representatives

DISTRICT SUPPLEMENTAL INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS (9-12) CURRICULAR AREA Agricultural and Environmental Education COURSE Environmental Education Grade(s): 9-12 PUBLISHER TITLE AUTHOR ISBN-10© YR Adpt Naturegraph Publishers Californian Wildlife Region, 3rd Revised and Brown0879612010 1999 1976 Expanded Ed. University of California Press Introduction to California Plant Life Ornduff, et al.0520237048 2003 1976 COURSE Floral Occupations Grade(s): 10-12 PUBLISHER TITLE AUTHOR ISBN-10© YR Adpt Ortho Books All About Houseplants Ortho Books0897214277 1999 1976 COURSE Floriculture Grade(s): 7-12 PUBLISHER TITLE AUTHOR ISBN-10© YR Adpt Ortho Books All About Houseplants Ortho Books0897214277 1999 1976 COURSE Forestry Grade(s): 9-12 PUBLISHER TITLE AUTHOR ISBN-10© YR Adpt Naturegraph Publishers Californian Wildlife Region, 3rd Revised and Brown0879612010 1999 1976 Expanded Ed. University of California Press Introduction to California Plant Life Ornduff, et al.0520237048 2003 1976 University of California Press Native Shrubs of Southern California Raven0520010507 1966 1976 COURSE Horticulture Grade(s): 6-12 PUBLISHER TITLE AUTHOR ISBN-10© YR Adpt Ortho Books All About Bulbs Ortho Books0897214250 1999 1986 Ortho Books All About Masonry Basics Ortho Books0897214382 2000 1986 Ortho Books All About Pruning Ortho Books0897214293 1999 1986 Ortho Books All About Roses Ortho Books0897214285 1999 1986 Wednesday, February 28, 2007 Page 1 of 343 Ortho Books All About Vegetables Ortho Books0897214196 1999 1978 Thomson Learning/Delmar Landscaping: Principles and Practices, 5th Ed., Ingels0827367368 1997 1978 Instructor's Guide Thomson Learning/Delmar Landscaping: Principles and Practices, 5th Ed., Ingels082736539X 1997 1999 Residential Design Workbook Thomson Learning/Delmar Landscaping: Principles and Practices, 5th Ed., Ingels0827365403 1997 1999 Residential Design Workbook, Instructor's Guide Thomson Learning/Delmar Landscaping: Principles and Practices, 6th Ed. -

Graphic Horror Teacher Tips & Activities

Graphic Horror Teacher Tips & Activities Illustration from Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde Based on the series Graphic Classics published by Magic Wagon, a division of ABDO. 1-800-800-1312 • www.abdopublishing.com Not for resale • Photocopy and adapt as needed for classroom and library use. Table Of Contents Comic book text is short, but that doesn’t mean students don’t learn a lot from it! Comic books and graphic novels can be used to teach reading processes and writing techniques, such as pacing, as well as expand vocabulary. Use this PDF to help students get more out of their comic book reading. Here are some of the projects you can give to your students to make comics educational and enjoyable! General Activities Publication History & Research --------------------------------- 1 Book vs. Movie vs. Graphic Novel ----------------------------- 2 Shared Reading & Fluency Practice --------------------------- 3 Scary Horror Stories ------------------------------------------------ 4 Create a Ghost Story ---------------------------------------------- 4 Work with Your Library -------------------------------------------- 5 Activities For Each Story The Creature from the Depths ---------------------------------- 6 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde -------------------------------------------- 7 Frankenstein ----------------------------------------------------------- 8 The Legend of Sleepy Hollow ----------------------------------- 9 Mummy ------------------------------------------------------------------ 10 Werewolf ---------------------------------------------------------------- -

Libro Gratis Dracula, 2 (Graphic Classics)

Register Free To Download Files | File Name : Dracula, 2 (Graphic Classics) PDF DRACULA, 2 (GRAPHIC CLASSICS) Tapa blanda Abreviado, 2 junio 2020 Author : Descripcin del productoBiografa del autorAbraham 'Bram' Stoker (1847 - 1912) was educated at Trinity College, Dublin and joined the Irish Civil Service before his love of theatre led him to become the unpaid drama critic for the Dublin Mail. He went on to act as as manager and secretary for the actor Sir Henry Irving, while writing his novels, the most famous of which is Dracula. Abraham (Bram) Stoker was an Irish writer, best known for his Gothic classic Dracula, which continues to influence horror writers and fans more than 100 years after it was first published.Educated at Trinity College, Dublin, in science, mathematics, oratory, history, and composition, Stoker's writing was greatly influenced by his father's interest in theatre and his mother's gruesome stories ... I collect graphic novels based on classic literature, so I had high hopes for this series by Barron's. In addition to Dracula, they've also published Treasure Island, Frankenstein, Kidnapped, Moby-Dick, and Journey to the Center of the Earth (maybe others I'm unaware of too). 'Dracula (Dover Graphic Novel Classics)' is a faithful adaptation of the novel told in graphic novel format. As a bonus, all the art is presented black and white so that it can be colored. It's all here. The creepy castle and creepier Count Dracula. The Harkners, Van Helsing and Renfield. The dark and tragic death. This item: Dracula Graphic Novel (Illustrated Classics) by Bram Stoker Paperback $9.95. -

Oxford Conference for the Book Participants, 2003–2012

Oxford Conference for the Book Participants, 2003–2012 JEFFREY RENARD ALLEN is the author of two collections of poetry, Stellar Places and Harbors and Saints, and a novel, Rails Under My Back, which won the Chicago Tribune’s Heartland Prize for Fiction. He has also published essays, poems, and short stories in numerous publications and is currently completing his second novel, Song of the Shank, based on the life of Thomas Greene Wiggins, a 19th-century African American piano virtuoso and composer who performed under the stage name Blind Tom. Allen is an associate professor of English at Queens College of the City University of New York and an instructor in the MFA writing program at New School University. (2008) STEVE ALMOND is the author of the story collections My Life in Heavy Metal and The Evil B. B. Chow and Other Stories, as well as the nonfiction work Candyfreak. Almond has published stories and poems in such publications as Playboy, Tin House, and Zoetrope: All-Story; and many have been anthologized. He is a regular commentator on the NPR affiliate WBUR in Boston and teaches creative writing at Boston College. (2005) STEVEN AMSTERDAM is the author of Things We Didn’t See Coming, a debut collection of stories published to rave reviews in February 2009. Amsterdam, a native New Yorker, moved to Melbourne, Australia, in 2003, where he is employed as a psychiatric nurse and is writing his second book. (2010) BILL ANDERSON is the second child and older son of Walter Anderson and his wife, Agnes Grinstead Anderson. -

From Michael Strogoff to Tigers and Traitors ― the Extraordinary Voyages of Jules Verne in Classics Illustrated

Submitted October 3, 2011 Published January 27, 2012 Proposé le 3 octobre 2011 Publié le 27 janvier 2012 From Michael Strogoff to Tigers and Traitors ― The Extraordinary Voyages of Jules Verne in Classics Illustrated William B. Jones, Jr. Abstract From 1941 to 1971, the Classics Illustrated series of comic-book adaptations of works by Shakespeare, Hugo, Dickens, Twain, and others provided a gateway to great literature for millions of young readers. Jules Verne was the most popular author in the Classics catalog, with ten titles in circulation. The first of these to be adapted, Michael Strogoff (June 1946), was the favorite of the Russian-born series founder, Albert L. Kanter. The last to be included, Tigers and Traitors (May 1962), indicated how far among the Extraordinary Voyages the editorial selections could range. This article explores the Classics Illustrated pictorial abridgments of such well-known novels as 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and Around the World in 80 Days and more esoteric selections such as Off on a Comet and Robur the Conqueror. Attention is given to both the adaptations and the artwork, generously represented, that first drew many readers to Jules Verne. Click on images to view in full size. Résumé De 1941 à 1971, la collection de bandes dessinées des Classics Illustrated (Classiques illustrés) offrant des adaptations d'œuvres de Shakespeare, Hugo, Dickens, Twain, et d'autres a fourni une passerelle vers la grande littérature pour des millions de jeunes lecteurs. Jules Verne a été l'auteur le plus populaire du catalogue des Classics, avec dix titres en circulation. -

Visualizing the Romance: Uses of Nathaniel Hawthorne's Narratives in Comics1

Visualizing the Romance: Uses of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Narratives in Comics1 Derek Parker Royal Classic works of American literature have been adapted to comics since the medium, especially as delivered in periodical form (i.e., the comic book), first gained a pop cultural foothold. One of the first texts adapted by Classic Comics, which would later become Classics Illustrated,2 was James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans, which appeared in issue #4, published in August 1942. This was immediately followed the next month by a rendering of Moby-Dick and then seven issues later by adaptations of two stories by Washington Irving, “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Headless Horseman.”3 As M. Thomas Inge points out, Edgar Allan Poe was one of the first, and most frequent, American authors to be translated into comics form (Incredible Mr. Poe 14), having his stories adapted not only in early issues of Classic Comics, but also in Yellow- jacket Comics (1944–1945) and Will Eisner’s The Spirit (1948).4 What is notable here is that almost all of the earliest adaptations of American literature sprang not only from antebellum texts, but from what we now consider classic examples of literary romance,5 those narrative spaces between the real and the fantastic where psychological states become the scaffolding of national and historical morality. It is only appropriate that comics, a hybrid medium where image and text often breed an ambiguous yet pliable synthesis, have become such a fertile means of retelling these early American romances. Given this predominance of early nineteenth-century writers adapted to the graphic narrative form, it is curious how one such author has been underrepresented within the medium, at least when compared to the treatment given to his contemporaries. -

THE COMIC THAT SAVED MARVEL” TURNS $9.95 in the USA

Roy Thomas’Star-Crossed LORDIE, LORDIE! Comics Fanzine “THE COMIC THAT SAVED MARVEL” TURNS $9.95 In the USA 40!40! No.145 March 2017 WHEN YOU WISH UPON A STAR BE CAREFUL YOU DON’T WIND UP WITH WARS NOW! 100 PAGES IN FULL COLOR! 1 82658 00092 9 "MAKIN' WOOKIEE" with CHAYKIN & THOMAS Vol. 3, No. 145 / March 2017 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Christopher Day Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck J.T. Go (Assoc. Editor) Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) Ronn Foss, Biljo White Mike Friedrich Contents Proofreaders Writer/Editorial: Star Wars—The Comic Book—Turns 40! . 2 Rob Smentek Makin’ Wookiee. 3 William J. Dowlding Roy Thomas tells Richard Arndt about the origins and pitfalls of Marvel’s 1977 Star Wars Cover Artist comic. Howard Chaykin Howard Chaykin On Star Wars . 54 Cover Colorist The artist/co-adapter of Star Wars #1-10 takes a brief look backward. Unknown Rick Hoberg On Star Wars . 58 With Special Thanks to: From helping pencil Star Wars #6—to a career at Lucasfilm. Rob Allen Jim Kealy Heidi Amash Paul King Bill Wray On Star Wars. 63 Pedro Angosto Todd Klein Rick Hoberg dragged him into inking Star Wars #6—and Bill’s glad he did! Richard J. Arndt Michael Kogge Rodrigo Baeza Paul Kupperberg The 1978 Star Wars Comic Adaptation . 67 Bob Bailey Vicki Crites Lane Lee Harsfeld takes us on a tour of veteran comics artist Charles Nicholas’ version of Mike W. -

An Annotated Bibliography of Adult Literacy Resources

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 333 140 CE 058 114 AUTHOR Campbell, Pat TITLE An Annotated Bibliography of Adult Literacy Resources. Second Edition. INSTITUTION PROSPECTS Adult Literacy Association, Edmonton (Alberta). SPONS AGENCY Alberta Dept. of Education, Edmonton.; Department of the Secretary of State, Ottawa (Ontario). Multiculturalism Directorate. PUB DATE 91 NOTE 135p.; For the first edition, see ED 308 285. AVAILABLE FROMPROSPECTS Adult Literacy Association, 9913 108 Avenue, Edmonton, Alberta T5H 1A5 ($10.00). PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Adult Basic Education; *Adult Literacy; Annotated Bibliographies; Basic Skills; Biographies; Consumer Education; *Daily Living Skills; Employment; *Fiction; First Aid; Foreign Countries; Functional Literacy; Health; Individual Development; *Literacy Education; *Nonfiction; Ree.'ing Comprehension; Skill Development; Spelling; Supplementary Reading Materials; Videotape Recordings; Vocabulary; Word Recognition; Workbooks; Writing (Composition) ABSTRACT This annotated bibliography lists 183 books dealing with adult literacy under 10 main categories: life skills; biographies; nonfiction; fiction; work identification workbooks; comprehension workbooks; skill development series; spelling workbooks; vocabulary workbooks; writing workbooks; and video irograms. The categories are further subdivided into up to six areas so that more specific information may be located. The life skills category is subdivided into personal development, -

Recommended Titles Sorted by Age Group

Recommended Graphic Novels Sorted By Age Age Rating Title Author Year Genre Publisher Price Additional Information All Adventures of Tintin: Tintin in Herge 1994 Adventure Little, Brown $17.99 HC America (v.1-7) All Akiko Pocket Books (3 vols.) Mark Crilley 1997 Fantasy Sirius $12.95 Digest All Amelia Rules!: The Whole World's Jimmy Gownley 2003 Humor iBooks $14.95 SC Gone Crazy All Amelia Rules!: What Makes You Jimmy Gownley 2004 Humor iBooks $14.95 SC Happy All Archie American Series: Best of the Victor Gorelick 1998 Humor Archie Comic Books $9.95 (-11.95) Digest; Price changes (40's, 50's, 60's, 70's, 80's) depending on volume. All Asterix (14 v. translated) Rene Goscinny and 2005 Humor/ Adventure Orion $9.95 SC Albert Uderzo All Batman Adventures : Rogues Gallery Various Authors 2004 Superhero DC $6.95 Digest All Batman Adventures Vol.2: Shadows Various Authors 2004 Superhero DC $6.95 Digest and Masks All Bone: Out From Boneville (v.1-9) Jeff Smith 1991 Fantasy Cartoon Books/ Scholastic $9.95 Color-SC; HC 18.95; Scholastic currently reprinting in color; All Cartoon Cartoons: Name That Toon! Various Authors 2004 Humor DC $6.95 Digest (v.1-2) All Decoy: Storm of the Century Courtney Huddleston 2000 Action Penny Farthing $17.95 SC All Good-bye Chunky Rice Craig Thompson 1999 Slice of Life Top Shelf $14.95 SC All Groo the Wanderer (10 vols.) Sergio Aragones 1995 Humor Dark Horse $9.95 (-13.95) SC; Price changes depending on volume. All JLA: New World Order Grant Morrison 1997 Superhero DC $7.95 SC All Justice League Adventures : The Dan Slott, et al.