Readingsample

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Abstract of the Thesis Of

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Annie M. Chozinski for the degree of Master of Science in Horticulture presented on November 23. 1994. Title: The Evaluation of Cold Hardiness in Corvlus. Abstract approved: Shawn A. Mehlenbacher Anthesis of both staminate and pistillate flowers of Cory/us occurs in midwinter. To insure adequate pollination and nut set, these flowers must attain a sufficient hardiness level to withstand low temperatures. This study estimated cold hardiness of Cory/us cultivars and species using laboratory freezing of shoots without artificial hardening. In December, January and February of 1991-92 and 1992-93, one-year stems were collected 0 0 and frozen at regular intervals from -10 C to -38 C/ and visual browning assessed survival approximately 10 days after freezing. Elongated catkins were clipped prior to freezing. Percent flower bud survival was calculated and plotted against temperature. Linear regression generated an equation relating percent bud survival to temperature. From this equation, estimates of the LT^ (lethal temperature for 50% of the buds) was calculated for catkins, female inflorescences, and vegetative buds. C. avellana L. catkins, on average, were less hardy in both December and January than female inflorescences and vegetative buds. Maximum hardiness was reached in December and nearly all had elongated prior to the February freeze. Cultivars with the most hardy catkins were 'Morell', 'Brixnut', 'Creswell', 'Gem', 'Giresun OSU 54.080', 'Hall's Giant', 'Riccia di Talanico', 'Montebello' and 'Rode Zeller'. Maximum hardiness was observed for both vegetative and pistillate buds in January and was followed by a marked loss of hardiness in February. -

Optimization of Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction of Flat-Europe Hybrid Hazelnut (Corylus Heterophylla Fisch

Biotechnology Journal International 17(4): 1-8, 2017; Article no.BJI.31140 Previously known as British Biotechnology Journal ISSN: 2231–2927, NLM ID: 101616695 SCIENCEDOMAIN international www.sciencedomain.org Optimization of Aqueous Enzymatic Extraction of Flat-Europe Hybrid Hazelnut (Corylus heterophylla Fisch. × C. avellana L.) Oil and Analysis of Its Components Chunmao Lv1*, Na Liu1, Xianjun Meng1, Changying Lu1 and Xiao Li1 1College of Food Science, Shenyang Agricultural University, Shenyang 110866, P. R. China. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between all authors. Author CL designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the protocol and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors NL, CL and XM managed the analyses of the study. Author XL managed the literature searches. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/BJI/2017/31140 Editor(s): (1) Ghousia Begum, Toxicology Unit, Biology Division, Indian Institute of Chemical Technology, Hyderabad, India. Reviewers: (1) Gyula Oros, PPI HAS, Budapest, Hungary. (2) Lorna T. Enerva, Polytechnic University of the Philippines, Philippines. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/17872 Received 22nd December 2016 Accepted 30th January 2017 Original Research Article th Published 17 February 2017 ABSTRACT Aim: The research aimed to evaluate the technological factors of the composite enzymatic extraction of Flat-European hybrid hazelnut oil, and analyze the fatty acid composition, to lay the foundations for the industrialized production of this oil. Study Design: Based on single factor tests, the best conditions for the aqueous enzymatic extraction of the oil determined by response surface analysis. -

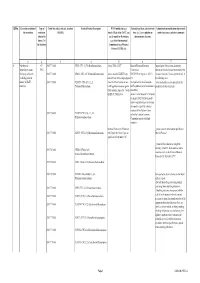

Qrno. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 CP 2903 77 100 0 Cfcl3

QRNo. General description of Type of Tariff line code(s) affected, based on Detailed Product Description WTO Justification (e.g. National legal basis and entry into Administration, modification of previously the restriction restriction HS(2012) Article XX(g) of the GATT, etc.) force (i.e. Law, regulation or notified measures, and other comments (Symbol in and Grounds for Restriction, administrative decision) Annex 2 of e.g., Other International the Decision) Commitments (e.g. Montreal Protocol, CITES, etc) 12 3 4 5 6 7 1 Prohibition to CP 2903 77 100 0 CFCl3 (CFC-11) Trichlorofluoromethane Article XX(h) GATT Board of Eurasian Economic Import/export of these ozone destroying import/export ozone CP-X Commission substances from/to the customs territory of the destroying substances 2903 77 200 0 CF2Cl2 (CFC-12) Dichlorodifluoromethane Article 46 of the EAEU Treaty DECISION on August 16, 2012 N Eurasian Economic Union is permitted only in (excluding goods in dated 29 may 2014 and paragraphs 134 the following cases: transit) (all EAEU 2903 77 300 0 C2F3Cl3 (CFC-113) 1,1,2- 4 and 37 of the Protocol on non- On legal acts in the field of non- _to be used solely as a raw material for the countries) Trichlorotrifluoroethane tariff regulation measures against tariff regulation (as last amended at 2 production of other chemicals; third countries Annex No. 7 to the June 2016) EAEU of 29 May 2014 Annex 1 to the Decision N 134 dated 16 August 2012 Unit list of goods subject to prohibitions or restrictions on import or export by countries- members of the -

The Role of Forage Availability on Diet Choice and Body Condition in American Beavers (Castor Canadensis)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers National Park Service 2013 The oler of forage availability on diet choice and body condition in American beavers (Castor canadensis) William J. Severud Northern Michigan University Steve K. Windels National Park Service Jerrold L. Belant Mississippi State University John G. Bruggink Northern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark Severud, William J.; Windels, Steve K.; Belant, Jerrold L.; and Bruggink, John G., "The or le of forage availability on diet choice and body condition in American beavers (Castor canadensis)" (2013). U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers. 124. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark/124 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Park Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Mammalian Biology 78 (2013) 87–93 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Mammalian Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mambio Original Investigation The role of forage availability on diet choice and body condition in American beavers (Castor canadensis) William J. Severud a,∗, Steve K. Windels b, Jerrold L. Belant c, John G. Bruggink a a Northern Michigan University, Department of Biology, 1401 Presque Isle Avenue, Marquette, MI 49855, USA b National Park Service, Voyageurs National Park, 360 Highway 11 East, International Falls, MN 56649, USA c Carnivore Ecology Laboratory, Forest and Wildlife Research Center, Mississippi State University, Box 9690, Mississippi State, MS 39762, USA article info abstract Article history: Forage availability can affect body condition and reproduction in wildlife. -

Filberts PART I

Station Bulletin 208 August, 1924 Oregon Agricultural College Experiment Station Filberts PART I. GROWING FILBERTS IN OREGON PART II. EXPERIMENTAL DATA ON FILBERT POLLINATION By C. E. SCHUSTER CORVALLIS, OREGON The regular bulletins of the Station are sent free to the residents of Oregon who request them. BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE OREGON AGRICULTURAL COLLEGE AND EXPERIMENT STATION HON.J. K. WEATI-IERFORS, President Albany I-ION. JEFEERSON MYERS, Secretary Portland Hon. B. F. IRVINE, Treasurer Portland HON.WALTER M. PIERCE, Governor Salem - HON.SAss A. KOZER, Secretary of State--.. - Salem I-ION. J A. CHURCHILL, Superintendent of Public instruction ......Salem HON. GEommcE A. PALM ITER, Master of State Grange - Hood River - HON. K. B. ALDRICH . - . .Pertdleton Hon. SAM H. BROSvN Gervams HON.HARRY BAILEY .......... Lakeview I-ION. Geo. M. CORNWALL Portland Hon. M. S. \OODCOCX Corvallis Hon. E. E. \VILON Corvallis STATION STAFF 'N. J. KERR, D.Sc., LL.D... President J. T. JARDINE, XIS Director E. T. DEED, B.S., AD... Editor H. P. BARSS, A.B., S.M - - .Plant Pathologist B. B. BAYLES - Jr Plant Breeder, Office of Cer. loses., U. S. Dept. of Agri. P. M.BRAND-C,B.S , A M Dairy Husbandmami - Horticulturist (Vegetable Gardening) A.G. G. C. BOUQUET, BROWN, B.S B.......Horticulturist, Hood River Br Exp. Station, Hood River V. S. BROWN, AD., M S Horticulturist in Charge D. K. BULL1S, B.S - Assistant Chemist LEROY CHILOC, AD - .Supt Hood River Branch Exp. Station, Hood River V. Corson, MS. .. Bacteriologist K. DEAN, B.S..............Supt. Umatilla Brsnch Exp. Station, Hermiston FLOYD M. -

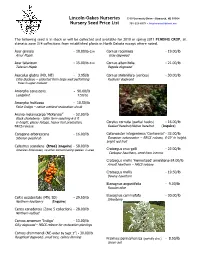

Nursery Price List

Lincoln-Oakes Nurseries 3310 University Drive • Bismarck, ND 58504 Nursery Seed Price List 701-223-8575 • [email protected] The following seed is in stock or will be collected and available for 2010 or spring 2011 PENDING CROP, all climatic zone 3/4 collections from established plants in North Dakota except where noted. Acer ginnala - 18.00/lb d.w Cornus racemosa - 19.00/lb Amur Maple Gray dogwood Acer tataricum - 15.00/lb d.w Cornus alternifolia - 21.00/lb Tatarian Maple Pagoda dogwood Aesculus glabra (ND, NE) - 3.95/lb Cornus stolonifera (sericea) - 30.00/lb Ohio Buckeye – collected from large well performing Redosier dogwood Trees in upper midwest Amorpha canescens - 90.00/lb Leadplant 7.50/oz Amorpha fruiticosa - 10.50/lb False Indigo – native wetland restoration shrub Aronia melanocarpa ‘McKenzie” - 52.00/lb Black chokeberry - taller form reaching 6-8 ft in height, glossy foliage, heavy fruit production, Corylus cornuta (partial husks) - 16.00/lb NRCS release Beaked hazelnut/Native hazelnut (Inquire) Caragana arborescens - 16.00/lb Cotoneaster integerrimus ‘Centennial’ - 32.00/lb Siberian peashrub European cotoneaster – NRCS release, 6-10’ in height, bright red fruit Celastrus scandens (true) (Inquire) - 58.00/lb American bittersweet, no other contaminating species in area Crataegus crus-galli - 22.00/lb Cockspur hawthorn, seed from inermis Crataegus mollis ‘Homestead’ arnoldiana-24.00/lb Arnold hawthorn – NRCS release Crataegus mollis - 19.50/lb Downy hawthorn Elaeagnus angustifolia - 9.00/lb Russian olive Elaeagnus commutata -

Diversity of Wisconsin Rosids

Diversity of Wisconsin Rosids . oaks, birches, evening primroses . a major group of the woody plants (trees/shrubs) present at your sites The Wind Pollinated Trees • Alternate leaved tree families • Wind pollinated with ament/catkin inflorescences • Nut fruits = 1 seeded, unilocular, indehiscent (example - acorn) *Juglandaceae - walnut family Well known family containing walnuts, hickories, and pecans Only 7 genera and ca. 50 species worldwide, with only 2 genera and 4 species in Wisconsin Carya ovata Juglans cinera shagbark hickory Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Leaves pinnately compound, alternate (walnuts have smallest leaflets at tip) Leaves often aromatic from resinous peltate glands; allelopathic to other plants Carya ovata Juglans cinera shagbark hickory Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family The chambered pith in center of young stems in Juglans (walnuts) separates it from un- chambered pith in Carya (hickories) Juglans regia English walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Trees are monoecious Wind pollinated Female flower Male inflorescence Juglans nigra Black walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Male flowers apetalous and arranged in pendulous (drooping) catkins or aments on last year’s woody growth Calyx small; each flower with a bract CA 3-6 CO 0 A 3-∞ G 0 Juglans cinera Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Female flowers apetalous and terminal Calyx cup-shaped and persistant; 2 stigma feathery; bracted CA (4) CO 0 A 0 G (2-3) Juglans cinera Juglans nigra Butternut, white -

Plastomes of Betulaceae and Phylogenetic Implications

Journal of Systematics JSE and Evolution doi: 10.1111/jse.12479 Research Article Plastomes of Betulaceae and phylogenetic implications † † Xiao-Yue Yang1 , Ze-Fu Wang2 , Wen-Chun Luo1, Xin-Yi Guo2, Cai-Hua Zhang1, Jian-Quan Liu1,2, and Guang-Peng Ren1* 1State Key Laboratory of Grassland Agro-Ecosystem, School of Life Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000, China 2Key Laboratory of Bio-Resource and Eco-Environment of Ministry of Education, College of Life Sciences, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610000, China † These authors contributed equally to this work. *Author for correspondence. E-mail: [email protected] Received 4 July 2018; Accepted 16 November 2018; Article first published online31 xx December Month 2019 2018 Abstract Betulaceae is a well-defined family of Fagales, including six living genera and more than 160 modern species. Species of the family have high ecological and economic value for the abundant production of wood. However, phylogenetic relationships within Betulaceae have remained partly unresolved, likely due to the lack of a sufficient number of informative sites used in previous studies. Here, we re-investigate the Betulaceae phylogeny with whole chloroplast genomes from 24 species (17 newly assembled), representing all genera of the family. All the 24 plastomes are relatively conserved with four regions, and each genome is 158–161 kb long, with 111 genes. The six genera are all monophyletic in the plastome tree, whereas Ostrya Scop. is nested in the Carpinus clade in the internal transcribed spacer tree. Further incongruencies are also detected within some genera between species. Incomplete lineage sorting and/or hybrid introgression during the diversification of the family could account for such incongruencies. -

Nut Trees - 2021

NUT TREES - 2021 CHESTNUT – Chinese Castanea mollissima ‘Improved’ (Seed grown) #3 #7 pot A selection from a superior orchard strain with unusual vigor, uniformity, disease-resistance and superior nut production. At least two seedlings or cultivars must be planted within 100 to 200 feet of each other to ensure cross-pollination and optimal fruit set. Seedlings commonly bear fruit in four to seven years. Mature trees may yield 35 to 55 pounds of nuts each year. Grows 30- 60 feet tall and 25 feet wide. PECAN Carya illinoinensis Pollinate with another variety of pecan for bigger crops. Grows 50' tall or more. ‘Kanza’ (Grafted) #3 pot Quality nuts that ripen before other varieties. Superior cold hardiness, disease resistant. 52% kernel. Grows 70' tall, 40-75' wide. ‘Lakota’ (Grafted) #3 pot High-quality nuts shell easily yielding cream-to-golden kernels with rich flavor. Early maturing. Strong, wind-resistant tree, disease-resistant to pecan scab. Ripens in mid- to late-October. ‘Peruque’ (Grafted) #3 pot Early season producer derived from a selection of native seedlings near the Mississippi River. Average production is 81 nuts per pound, with 59% kernel. Kernels are golden, with tight dorsal grooves and a deep basal cleft. Grows 70' tall, 40-75' wide. Native. AMERICAN FILBERT #3 pot Corylus americana Native shrub, excellent for naturalizing, woodland gardens and shade areas. Showy male flowers (catkins) add early spring interest, dark green leaves turn a beautiful kaleidoscope of colors in the fall. The nuts mature from September to October. Grows 8’ x 8’ forming a thicket. WALNUT Black Walnut – Juglans nigra #15 Native tree that provides excellent shade for large properties. -

RECOMMENDED SMALL TREES for CITY USE (Less Than 30 Feet)

RECOMMENDED SMALL TREES FOR CITY USE (Less than 30 feet) Scientific Name Common Name Comments Amelanchier arborea Serviceberry, shadbush, Juneberry Very early white flowers. Good for pollinators and wildlife. Amorpha fruticosa False indigobush Can form clusters. Legume. Good for pollinators. Asimina triloba Paw-paw Excellent edible fruit. Good for wildlife. Can be hard to establish. Chionanthus virginicus Fringe Tree Cornus mas Cornelian Cherry (Dogwood) Cornus spp. Shrub dogwoods – Gray, Pale, Can form clusters. Very good for wildlife Red-0sier, Alternate, Silky & pollinators. Corylus americana Hazelnut Very good for wildlife. Crataegus pruinosa Frost hawthorn Thorny, attractive white flowers. Good for wildlife. Hamamelis virginiana Witchhazel Good for pollinators Lindera benzoin Spicebush Very good for butterflies. Sweet-smelling aromatic leaves Malus spp. Crabapples – Iowa and Prairie Can get 25’ tall. Beautiful spring flowers. Good for wildlife. Oxydendrum arborum Sourwood Prunus americana Wild or American plum Can form clusters. Very good for wildlife. Can get 20’ tall. Prunus virginiana Chokecherry Can get 30’ tall. Good for wildlife and pollinators. Rhus aromatic Aromatic sumac Attractive to bees and butterflies. Sambucus canadensis Elderberry Edible black berries – good for wildlife and pollinators. Viburnum spp. Arrowwood, nannyberry, Early white flower clusters, very good for blackhaw wildlife. NOTES: • All the above small trees/shrubs prefer moist soil. Some, like the false Indigobush, silky and red-osier dogwoods, spicebush, and elderberry, can tolerate wet soils. None do well on dry sandy or rocky soils. • All prefer at least 3 hours of sun per day, and flower better when they can get 6 hours or more per day. Spicebush can tolerate full shade, but flowers better with 3-6 hours of sun. -

Hazelnuts Resistant to Eastern Filbert Blight: Are We There Yet?

Hazelnuts Resistant to Eastern Filbert Blight: Are We There Yet? Thomas J. Molnar, Ph.D. Plant Biology and Pathology Dept. Rutgers University The American Chestnut Society Annual Meeting October 22, 2011 Nut Tree Breeding at Rutgers Based on the tremendous genetic improvements demonstrated in several previously underutilized turf species, Dr. C. Reed Funk strongly believed similar work could be done with nut trees Title of project started in 1996: Underutilized Perennial Food Crops Genetic Improvement Tom Molnar and Reed Funk Program Adelphia Research Farm August 2001 Nut Breeding at Rutgers Starting in 1996, species of interest included – black walnuts, Persian walnuts and heartnuts – pecans, hickories Pecan shade trial – chestnuts, Adelphia 2000 – almonds, – hazelnuts We built a germplasm collection of over 25,000 trees planted across five Rutgers research farms – Cream Ridge Fruit Research Farm (Cream Ridge, NJ) – Adelphia Research Farm (Freehold, NJ) Pecan shade trial Adelphia 2008 – HF1, HF2, HF3 (North Brunswick, NJ) Nut Breeding at Rutgers Goals – Identify species that show the greatest potential for New Jersey and Mid- Atlantic region – Develop breeding program to create superior well- adapted cultivars that reliably produce high- quality, high-value crops • while requiring reduced inputs of pesticides, fungicides, management, etc. Nut Breeding at Rutgers While most species showed great promise for substantial improvement, we had to narrow our focus to be most effective Hazelnuts stood out as the species where we could make significant contributions in a relatively short period of time – Major focus since 2000 Hazelnuts at Rutgers Why we chose to focus on hazelnuts: – success of initial plantings made in 1996/1997 with few pests and diseases – short generation time and small plant size (4 years from seed to seed) – wide genetic diversity and the ability to hybridize different species – ease of making controlled crosses – backlog of information and breeding advances – existing technologies and markets for nuts Hazelnuts: Corylus spp. -

CBD First National Report

FIRST NATIONAL REPORT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA TO THE UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY July 2010 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................... 3 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 4 2. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Geographic Profile .......................................................................................... 5 2.2 Climate Profile ...................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Population Profile ................................................................................................. 7 2.4 Economic Profile .................................................................................................. 7 3 THE BIODIVERSITY OF SERBIA .............................................................................. 8 3.1 Overview......................................................................................................... 8 3.2 Ecosystem and Habitat Diversity .................................................................... 8 3.3 Species Diversity ............................................................................................ 9 3.4 Genetic Diversity ............................................................................................. 9 3.5 Protected Areas .............................................................................................10