PLAYING the SHELL GAME FOUR WAYS SHELL IMPEDES the JUST TRANSITION Rhodante Ahlers & Ilona Hartlief Contributing Authors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gevallen Op Het Binnenhof

CHARLOTTE BRAND Gevallen op het Binnenhof Afgetreden ministers en staatssecretarissen 1918-1966 Boom – Amsterdam Gevallen op het Binnenhof Afgetreden ministers en staatssecretarissen 1918-1966 Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus, volgens het besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 8 januari 2016 om 14.30 uur precies door Charlotte Josephina Maria Brand geboren op 4 februari 1982 te Roermond Inhoud Inleiding 11 hoofdstuk 1 Ministers Geslachtofferd door de kaMer 27 Een katholiek aan het roer 27 Invulling Oorlog en Marine baart zorgen 29 ‘Daar zien ze me nooit meer terug!’: minister van Marine Naudin ten Cate (1919) 31 Na aarzeling toch bewindsman 31 De kruisers als pijnpunt 35 Een fataal parlementair debuut 36 Ten val gebracht door zijn eigen staf: minister van Marine Bijleveld (1920) 40 Een burger op Marine 40 De kruisers zorgen opnieuw voor problemen 42 ‘Draaitol’ geslachtofferd 44 Napraten over de streek van Olivier 48 Begroting uitgekleed: minister van Oorlog Alting von Geusau (1920) 50 Slecht materieel en muitende soldaten 50 Bezuinigingen en hervormingen 51 Niemand blijft ‘voor zijn pleizier Minister van Oorlog’ 54 De begroting getorpedeerd 56 Gestrand in het zicht van het Poppenleger: minister van Oorlog en Marine Pop (1921) 59 ‘Men moet het aandurven van het defensie-departement te maken een politiek departement’ 59 Een nieuwe minister met ‘militaire snorrebaard’ 63 Naar een ‘poppenleger’? 64 De nieuwe Dienstplichtwet -

Shell" Transport and Trading Company, Ltd

THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY May 21, 1955 The "Shell" Transport and Trading Company, Ltd. Greater Operational Activity Results in Increased Sales Volume Heavy Capital Expenditure Inescapable Substantially Enlarged World Consumption Sir Frederick Godber's views on Oil Prices HE Annual General Meeting of through the capitalization of part of ber, was widely appreciated and T The " Shell " Transport and the company's share premiums re favourably commented upon, as Trading Company, Limited, will be serve. affording an opportunity of following held on June 1 at The Chartered In more closely the current trading When commenting on this issue surance Institute, 20, Aldermanbury, results of the group. I am glad to in my statement last year, I said that say that this year we propose to London, E.C. one of its objects was to broaden the publish similar results on a quarterly The following is the statement by basis of the ownership of the com basis, and that figures for the first the Chairman, Sir Frederick Godber, pany. You may, therefore, be inter quarter will be available within a few which has been circulated with the ested to learn that during 1954 re weeks. report and accounts for the year end gistered Ordinary stockholders in ed December 31, 1954: — creased by approximately 10,000, and I will now proceed to the report in December numbered over 142,000. on the group financial results for The Board of Directors You will appreciate, of course, that 1954. Little more than a year after his the number of individuals who own THE ROYAL DUTCH/SHELL resignation from the board owing to the equity of the company must ill health, Sir Andrew Agnew, our exceed this figure by a substantial GROUP REPORT ON THE colleague for so many years, has margin, there being no record of those YEAR 1934 passed away. -

7-Eleven & Shell

MARCUS & MILLICHAP OFFERING MEMORANDUM Activity#Z0380619 7 - ELEVEN & SHELL 8541 WEST FREEWAY FORT WORTH, TEXAS 76116 OFFERING MEMORANDUM | 7 - ELEVEN & SHELL 8541 WEST FREEWAY, FORT WORTH, TEXAS 76116 INVESTMENT OVERVIEW INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS • Irreplaceable Off-Ramp Location • Absolute NNN Lease with Zero Landlord Responsibilities • Income Tax Free State • Corner Location with Dedicated Turn Lane • Large Pylon Sign with Freeway Visibility • 80,523 People in Three Mile Radius • 106,194 Vehicles Per Day on Interstate 30 • 7-Eleven is the World’s Largest Operator, Franchisor & Licensor of INVESTMENT SUMMARY Convenient Stores The Conway Group at Marcus & Millichap is pleased to present th • Fort Worth is the 4 Most Populous Metropolitan Area in the the sale of this 3,042 square foot 7-Eleven and Shell property in United States Fort Worth, Texas. The subject property operates as a NNN Lease, with zero landlord responsibilities. This convenient store sits on 0.74 acres of and, with filling stations present. Situated on a signalized OFFERING SUMMARY corner, with a dedicated turn lane and pylon signage, the subject property sees over 106,194 Vehicles Per Day on Interstate PRICE $1,974,000 30. Located in a Tax Free State, this 7-Eleven offers great visibility and easy access. NOI $101,640 th C A P R A T E 5.15 % Fort Worth is the 15 -Largest City in the United States, with a population of 875,000 people. Population growth is up 8.50 PRICE/SF $648.92 percent in a one mile radius from the property. RENT/SF $33.41 7-Eleven was founded in 1927 and has now grown and evolved L E A S E T Y P E NNN into an international chain of convenience stores, operating nearly 7,800 company-owned and franchised stores in North GROSS LEASABLE AREA 3,042 SF America. -

Oil and Gas Europe

Oil and Gas Europe Buyer Members Powered by Achilles JQS and FPAL, Oil and Gas Europe brings together two communities to provide buyers with a regional, searchable network of qualified suppliers within the European oil and gas supply chain. Below is a list of the buyers from Achilles JQS and FPAL with access to the Oil and Gas Europe Network. Company Name 4c Solutions AS BUMI ARMADA UK LTD Emerson Process Management AS 4Subsea BW Offshore Norway Endur FABRICOM AS A.S Nymo BW Offshore UK ENI UK Abyss Subsea AS Cairn Energy Plc Norway Enquest Advokatfirmaet Simonsen Vogt Wiig AS Cairn Energy UK Equinor (U.K) Ltd Advokatfirmaet Thommessen AS CAN Offshore ESSAR OIL (UK) Ltd Af Gruppen Norge AS Cape Industrial Services Ltd Evry AGR Well Management Limited Chevron North Sea Limited Expro Group Aibel AS Chrysaor Holdings Limited Fairfield Energy Ltd Aker Solutions Norway CNOOC Faroe Petroleum Aker Solutions UK CNR International (UK) Ltd Furmanite AS. Alpha Petroleum Resources Limited ConocoPhillips (U.K.) Ltd Gassco Altus Intervention AS Cosl Drilling Europe AS Glencore Apache North Sea Limited Cuadrilla Resources Ltd GLT-PLUS VOF Apply Sørco AS Dana Petroleum (UK) Gulf Marine Services Halliburton Manufacturing & Archer Norge AS Dea Norge Services Ltd Awilco Drilling Deepocean AS Halliburton Norway Baker Hughes Norway Deepwell Hammertech AS DEO Petroleum Plc Baker Hughes UK (Parkmead Group) Hess Beerenberg Corp Dof Subsea Norway AS Ikm Group Bluewater Services DOF Subsea UK Ltd Ineos Denmark BP Exploration Operating International Recarch Institute Of Company Ltd Dwellop AS Stavanger IRIS Achilles Information Limited | 7 Burnbank Business Centre Souterhead Road Altens Aberdeen AB12 3LF | www.achilles.com Achilles Information Limited | FirstPoint Supplybase - Supplier Pre-Qualification Terms and Conditions Version 2.0 0718 © Achilles Supplybase Pty Ltd 2011 Inventura AS Oranje Nassau Energy UK Ltd Spirit Energy Nederland IV Oil and Gas b.v. -

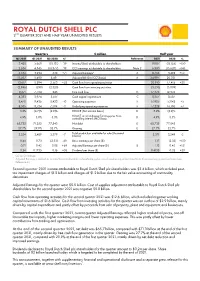

Shell QRA Q2 2021

ROYAL DUTCH SHELL PLC 2ND QUARTER 2021 AND HALF YEAR UNAUDITED RESULTS SUMMARY OF UNAUDITED RESULTS Quarters $ million Half year Q2 2021 Q1 2021 Q2 2020 %¹ Reference 2021 2020 % 3,428 5,660 (18,131) -39 Income/(loss) attributable to shareholders 9,087 (18,155) +150 2,634 4,345 (18,377) -39 CCS earnings attributable to shareholders Note 2 6,980 (15,620) +145 5,534 3,234 638 +71 Adjusted Earnings² A 8,768 3,498 +151 13,507 11,490 8,491 Adjusted EBITDA (CCS basis) A 24,997 20,031 12,617 8,294 2,563 +52 Cash flow from operating activities 20,910 17,415 +20 (2,946) (590) (2,320) Cash flow from investing activities (3,535) (5,039) 9,671 7,704 243 Free cash flow G 17,375 12,376 4,383 3,974 3,617 Cash capital expenditure C 8,357 8,587 8,470 9,436 8,423 -10 Operating expenses F 17,905 17,042 +5 8,505 8,724 7,504 -3 Underlying operating expenses F 17,228 16,105 +7 3.2% (4.7)% (2.9)% ROACE (Net income basis) D 3.2% (2.9)% ROACE on an Adjusted Earnings plus Non- 4.9% 3.0% 5.3% controlling interest (NCI) basis D 4.9% 5.3% 65,735 71,252 77,843 Net debt E 65,735 77,843 27.7% 29.9% 32.7% Gearing E 27.7% 32.7% Total production available for sale (thousand 3,254 3,489 3,379 -7 boe/d) 3,371 3,549 -5 0.44 0.73 (2.33) -40 Basic earnings per share ($) 1.17 (2.33) +150 0.71 0.42 0.08 +69 Adjusted Earnings per share ($) B 1.13 0.45 +151 0.24 0.1735 0.16 +38 Dividend per share ($) 0.4135 0.32 +29 1. -

Extracting the Best in Upstream Analysis |

Extracting the best in upstream analysis | www.worldexpro.com Extracting the best in upstream analysis | www.worldexpro.com Extracting the best in upstream analysis | www.worldexpro.com Why is World Expro essential reading? As oil prices continue to remain volatile and consuming nations become increasingly determined to secure access to energy supplies, choosing the right investment and the right business partner has never been more essential. Investing in new technologies to further push the boundaries of oil and gas exploration and production is becoming more and more crucial to companies to boost reserves and output. World Expro is the premier information source for the world’s upstream oil executives who need reliable and accurate intelligence to help them make critical business decisions. Aimed at senior board members, operations, procurement and E&P heads within the upstream industry World Expro provides a clear overview of the latest industry thinking regarding the key stages of exploration and production. Bonus distribution at key industry events, Further distribution of WEX on display at WEX on display at ADIPEC Abu Dhabi OSEA, Singapore Extracting the best in upstream analysis | www.worldexpro.com Circulation and Readership The key to World Expro’s success is its carefully targeted ABC-audited circulation. World Expro reaches key decision makers within state-owned and independent oil and gas producing companies, the contractor community and financial and consulting organisations. World Expro is read by personnel ranging from presidents and CEOs to heads of E&P, project managers and geophysicists to engineers. World Expro is distributed in March and September internationally at corporate, divisional/ regional and project level and has an estimated readership of 56,000 (publisher’s statement). -

Big Oil's Real Agenda on Climate Change

Big Oil’s Real Agenda on Climate Change How the oil majors have spent $1bn since Paris on narrative capture and lobbying on climate March 2019 Big Oil’s Real Agenda on Climate Change How the oil majors have spent $1Bn since Paris on narrative capture and lobbying on climate Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Detailed Results ........................................................................................................................................ 9 Big Oil and the US Elections ................................................................................................................ 17 Conclusions ............................................................................................................................................. 20 Appendix: Methodology ......................................................................................................................... 21 Appendix: Climate Scoring Profiles .................................................................................................. 22 1 InfluenceMap March 2019 Executive Summary ◼ This research finds that the five largest publicly-traded oil and gas majors (ExxonMobil, Royal Dutch Shell, Chevron, BP and Total) have invested over $1Bn of shareholder funds in the three -

The Economic Impacts of the Gulf of Mexico Oil and Natural Gas Industry

The Economic Impacts of the Gulf of Mexico Oil and Natural Gas Industry Prepared For Prepared By Executive Summary Introduction Despite the current difficulties facing the global economy as a whole and the oil and natural gas industry specifically, the Gulf of Mexico oil and natural gas industry will likely continue to be a major source of energy production, employment, gross domestic product, and government revenues for the United States. Several proposals have been advanced recently which would have a major impact on the industry’s activity levels, and the economic activity supported by the Gulf of Mexico offshore oil and natural gas industry. The proposals vary widely, but for the purpose of this report three scenarios were developed, a scenario based on a continuation of current policies and regulations, a scenario examining the potential impacts of a ban on new offshore leases, and a scenario examining the potential impacts of a ban on new drilling permits approvals in the Gulf of Mexico. Energy and Industrial Advisory Partners (EIAP) was commissioned by the National Ocean Industry Association (NOIA) to develop a report forecasting activity levels, spending, oil and natural gas production, supported employment, GDP, and Government Revenues in these scenarios. The scenarios developed in this report are based solely upon government and other publicly available data and EIAP’s own expertise and analysis. The study also included profiles of NOIA members to demonstrate the diverse group of companies which make up the offshore Gulf of Mexico oil and natural gas industry as well as a list of over 2,400 suppliers to the industry representing all 50 states. -

Of Power and Influence

OF POWER AND INFLUENCE HENRY DETERDING, ROYAL DUTCH SHELL’S UNOFFICIAL DIPLOMAT (1912-1922) TOM SCHOEN 6560334 UTRECHT UNIVERSITY MA THESIS: INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE 15/01/2020 Sir Henry Deterding1 1 Nationaal Archief, The Hague (hereafter NL-HaNa), ‘Photo Collection Henry Deterding’, catalogue number: 2.24.10.02, inventory number: 119-0210. (Date unknown) To Nicolaas Jacobus Snaas, the Schagen-Oil Man Abstract This thesis aims to analyse the role of Henry Deterding, the director-general of Royal Dutch Shell (RDS), as an unofficial ‘diplomat’ and non-state actor during two events in which the interests of RDS and that of the Dutch government collided. It tries to indicate as to what extent Deterding was able to exert power and influence vis-à-vis the Dutch government’s decision-makers in order to guard the business interests of the company. By analysing the contextual factors that led Deterding to decide to embark upon a campaign to influence the Dutch government’s decision-makers, and by focusing on the goals, modus operandi and interactions between Deterding and those decision-makers, this thesis provides answers to the raison d’être behind his corporate lobby and its effects. It provides insights as to why Deterding did this, how he operated and what effects it produced in relation to the decision- making process. The methodology of New Diplomatic History (NDH) has been absolutely vital in this respect. As NDH specifically aims to reveal, interpret and analyse the roles of private, non-state actors, this thesis has based its research on primary sources of private and business archives in particular, instead of traditionally studied government archives. -

Big Oil's Oily Grasp

Big Oil’s Oily Grasp The making of Canada as a Petro-State and how oil money is corrupting Canadian politics Daniel Cayley-Daoust and Richard Girard Polaris Institute December 2012 The Polaris Institute is a public interest research organization based in Canada. Since 1997 Polaris has been dedicated to developing tools and strategies to take action on major public policy issues, including the corporate power that lies behind public policy making, on issues of energy security, water rights, climate change, green economy and global trade. Polaris Institute 180 Metcalfe Street, Suite 500 Ottawa, ON K2P 1P5 Phone: 613-237-1717 Fax: 613-237-3359 Email: [email protected] www.polarisinstitute.org Cover image by Malkolm Boothroyd Table of Contents Introduction 1 1. Corporations and Industry Associations 3 2. Lobby Firms and Consultant Lobbyists 7 3. Transparency 9 4. Conclusion 11 Appendices Appendix A, Companies ranked by Revenue 13 Appendix B, Companies ranked by # of Communications 15 Appendix C, Industry Associations ranked by # of Communications 16 Appendix D, Consultant lobby firms and companies represented 17 Appendix E, List of individual petroleum industry consultant Lobbyists 18 Appendix F, Recurring topics from communications reports 21 References 22 ii Glossary of Acronyms AANDC Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada CAN Climate Action Network CAPP Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers CEAA Canadian Environmental Assessment Act CEPA Canadian Energy Pipelines Association CGA Canadian Gas Association DPOH -

Royal Dutch Shell Report on Payments to Governments for the Year 2018

ROYAL DUTCH SHELL REPORT ON PAYMENTS TO GOVERNMENTS FOR THE YEAR 2018 This Report provides a consolidated overview of the payments to governments made by Royal Dutch Shell plc and its subsidiary undertakings (hereinafter refer to as “Shell”) for the year 2018 as required under the UK’s Report on Payments to Governments Regulations 2014 (as amended in December 2015). These UK Regulations enact domestic rules in line with Directive 2013/34/EU (the EU Accounting Directive (2013)) and apply to large UK incorporated companies like Shell that are involved in the exploration, prospection, discovery, development and extraction of minerals, oil, natural gas deposits or other materials. This Report is also filed with the National Storage Mechanism (http://www.morningstar.co.uk/uk/nsm) intended to satisfy the requirements of the Disclosure Guidance and Transparency Rules of the Financial Conduct Authority in the United Kingdom This Report is available for download from www.shell.com/payments BASIS FOR PREPARATION - REPORT ON PAYMENTS TO GOVERNMENTS FOR THE YEAR 2018 Legislation This Report is prepared in accordance with The Reports on Payments to Governments Regulations 2014 as enacted in the UK in December 2014 and as amended in December 2015. Reporting entities This Report includes payments to governments made by Royal Dutch Shell plc and its subsidiary undertakings (Shell). Payments made by entities over which Shell has joint control are excluded from this Report. Activities Payments made by Shell to governments arising from activities involving the exploration, prospection, discovery, development and extraction of minerals, oil and natural gas deposits or other materials (extractive activities) are disclosed in this Report. -

Cash Flows of Five Oil Majors Can't Cover Dividends, Buybacks

Kathy Hipple, Financial Analyst 1 Clark Williams-Derry, Energy Finance Analyst Tom Sanzillo, Directory of Finance January 2020 Living Beyond Their Means: Cash Flows of Five Oil Majors Can’t Cover Dividends, Buybacks Companies Are Using Stopgap Asset Sales and New Long- Term Debt to Bridge Chronic Shortfalls for Funding Shareholder Dividends Since 2010, the world’s largest oil and gas companies have failed to generate enough cash from their primary business – selling oil, gas, refined products and petrochemicals – to cover the payments they have made to their shareholders. ExxonMobil, BP, Chevron, Total, and Royal Dutch Shell (Shell), the five largest publicly traded oil and gas firms, collectively rewarded stockholders with $536 billion in dividends and share buybacks since 2010, while generating $329 billion in free cash flow over the same period.1 (See Table 1.) The companies made up the $207 billion cash shortfall—equal to 39 percent of total shareholder distributions—primarily by selling assets and borrowing money. Table 1: Five Supermajors: Free Cash Flow, Shareholder Distributions, Cash Deficits, 2010 – 3Q 2019 (Billion $USD) Dividends and Free Cash Flow Deficit Buybacks Exxon-Mobil $137.8 $202.3 ($64.5) BP $13.2 $62.9 ($49.7) Chevron $47.3 $90.5 ($43.1) Total SA $29.4 $56.4 ($27.0) Shell $101.0 $123.9 ($22.9) Sum, 5 Supermajors $328.7 $535.9 ($207.2) Source: IEEFA, based on company financial reports. Totals may not add due to rounding. This practice reflects an underlying weakness in the fundamentals of contemporary oil and gas business models: revenues from the supermajors’ operations are not covering their core operational expenses and capital expenditures.