Religious Groups & “Affluenza”: Further Exploration of the TV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

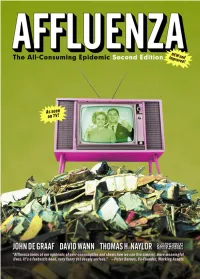

Affluenza: the All-Consuming Epidemic Second Edition

An Excerpt From Affluenza: The All-Consuming Epidemic Second Edition by John de Graaf, David Wann, & Thomas H. Naylor Published by Berrett-Koehler Publishers contents Foreword to the First Edition ix part two: causes 125 Foreword to the Second Edition xi 15. Original Sin 127 Preface xv 16. An Ounce of Prevention 133 Acknowledgments xxi 17. The Road Not Taken 139 18. An Emerging Epidemic 146 Introduction 1 19. The Age of Affluenza 153 20. Is There a (Real) Doctor in the House? 160 part one: symptoms 9 1. Shopping Fever 11 part three: treatment 2. A Rash of Bankruptcies 18 171 21. The Road to Recovery 173 3. Swollen Expectations 23 22. Bed Rest 177 4. Chronic Congestion 31 23. Aspirin and Chicken Soup 182 5. The Stress Of Excess 38 24. Fresh Air 188 6. Family Convulsions 47 25. The Right Medicine 197 7. Dilated Pupils 54 26. Back to Work 206 8. Community Chills 63 27. Vaccinations and Vitamins 214 9. An Ache for Meaning 72 28. Political Prescriptions 221 10. Social Scars 81 29. Annual Check-Ups 234 11. Resource Exhaustion 89 30. Healthy Again 242 12. Industrial Diarrhea 100 13. The Addictive Virus 109 Notes 248 14. Dissatisfaction Guaranteed 114 Bibliography and Sources 263 Index 276 About the Contributors 284 About Redefining Progress 286 vii preface As I write these words, a news story sits on my desk. It’s about a Czech supermodel named Petra Nemcova, who once graced the cover of Sports Illustrated’s swimsuit issue. Not long ago, she lived the high life that beauty bought her—jet-setting everywhere, wearing the finest clothes. -

Curing Our Affluenza by NORMAN WIRZBA

Copyright © 2003 The Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University 89 Curing Our Affluenza BY NORMAN WIRZBA Consumerism has an ambiguous, even destructive, legacy: it has provided status and freedom to some, but has not been successful in treating change and uncer- tainty, inequality and division. As these books discover, our “affluenza”—a feverish obsession to consume mate- rial goods—is not healthy for us or the creation as a whole. Its cure is not a call to dour asceticism, but rather an invitation to receive God’s extravagant grace. early two hundred years ago, Alexis de Tocqueville observed in Democracy in America that Americans, though living among the Nhappiest circumstances of any people in the world, are followed by a cloud that habitually hangs over their heads, a cloud that makes them serious, even sad, in the midst of their pleasures. Though they have cause for celebration, they never stop thinking of “the good things they have not got.” Consequently, they pursue prosperity with a “feverish ardor,” tor- mented by the suspicion that they have not chosen the quickest or shortest path to get it. “They clutch everything but hold nothing fast, and so lose grip as they hurry after some new delight.” Were he alive today, de Tocqueville would not need to change his words very much, perhaps adding only that the intensity of our ardor, the scope of our clutching, and the depth of our loss have increased sub- stantially. Having been advised by countless spiritual guides that money and the pursuit of material comfort will not bring us happiness, why do we still maintain this ambition as a personal, even national, quest? What is becom- 90 Consumerism ing clear to many in our society is that consumerism is not healthy for us or for the creation as a whole, and that it leads to anxiety, stress, boredom, and indigestion, all maladies with tremendous personal and social costs. -

Showcase USA: Simply Beautiful: Choosing an Uncluttered, Focused, Rich Life

Showcase USA: Simply Beautiful: Choosing an Uncluttered, Focused, Rich Life Sam Quick Robert Flashman Peter Hesseldenz Abstract The excessive, frenzied quality of American life has left more and more people yearning for balance and simplicity. According to the Trends Research Institute of Rhinebeck, New York, simplification is a leading trend of our times. The Cooperative Extension Service in Kentucky responded by developing a program called "Simply Beautiful." It seeks to teach people how to make the choices that allow them to align their financial lives with their values. The program gently guides people towards asking themselves if they are living the lives they want to live and if not, why not? Rationale for Program The good life, in America, has come to be equated with material possessions. Advertisers would have us believe that spending money leads to happiness. Wealth is a key component of the American Dream; we are encouraged to strive for it from very early on. For many, the images of wealth and the promises of happiness are too compelling to ignore or even look at critically. With easy credit readily available to today's consumers, many adopt a free-spending lifestyle, even if they can't afford it. What is the result? Massive consumer debt and, in many cases, bankruptcy. In 1993, 897,231 consumers filed for bankruptcy in the United States. This number rose to 1,367,364 in 1997, a 52 percent increase. The situation was even worse in Kentucky. The number rose from 12,421 in 1993 to 21,188 in 1997 for an increase of 71 percent (Jordan, 1999). -

JULIET B. SCHOR Department of Sociology Ph: 617-552-4056 Boston College

JULIET B. SCHOR Department of Sociology ph: 617-552-4056 Boston College fax: 617-552-4283 531 McGuinn Hall email: [email protected] 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill, MA 02467 PERSONAL DATA Born November 9, 1955; citizenship, U.S.A. POSITIONS Professor of Sociology, Boston College, July 2001-present. Department Chair, July 2005- 2008. Director of Graduate Studies, July 2011-January 2013. Associate Fellow, Tellus Institute. 2020-present. Matina S. Horner Distinguished Visiting Professor, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Studies, Harvard University, 2014-2015. Visiting Professor, Women, Gender and Sexuality, Harvard University, 2013. Visiting Professor, Yale School of Environment and Forestry, 2012, Spring 2010. Senior Scholar, Center for Humans and Nature, 2011. Senior Lecturer on Women’s Studies and Director of Studies, Women's Studies, Harvard University, 1997-July 2001. Acting Chair, 1998-1999, 2000-2001. Professor, Economics of Leisure Studies, University of Tilburg, 1995-2001. Senior Lecturer on Economics and Director of Studies in Women’s Studies, Harvard University, 1992-1996. Associate Professor of Economics, Harvard University, 1989-1992. Research Advisor, Project on Global Macropolicy, World Institute for Development Economics Research (WIDER), United Nations, 1985-1992. Assistant Professor of Economics, Harvard University, 1984-1989. Assistant Professor of Economics, Barnard College, Columbia University, 1983-84. Assistant Professor of Economics, Williams College, 1981-83. Research Fellow, Brookings Institution, 1980-81. 1 Teaching Fellow, University of Massachusetts, 1976-79. EDUCATION Ph.D., Economics, University of Massachusetts, 1982. Dissertation: "Changes in the Cyclical Variability of Wages: Evidence from Nine Countries, 1955-1980" B.A., Economics, Wesleyan University, 1975 (Magna Cum Laude) HONORS AND AWARDS Management and Workplace Culture Book of the Year, Porchlight Business Book Awards, After the Gig, 2020. -

The Bullfrog Films Collection from Docuseek2

The Bullfrog Films Collection on Docuseek2 currently features over 500 titles from the extensive Bullfrog Films catalog, with more being added regularly. With 40 years of history and a catalog of over 900 titles from which to draw, documentaries from Bullfrog Films are among the strongest available dealing with issues ranging from the environment, globalization and sustainability to human rights and social justice. Abandoned Blue Vinyl Detropia For Earth’s Sake Aboriginal Architecture Borderline Cases The Dhamma Brothers For the Love of Movies Addicted to Plastic Boys Will Be Men Diamond Road Force Of Nature Addiction Incorporated Breaking the Silence Dido and Aeneas The Forest For The Trees Affluenza Bringing It Home Diet for a Small Planet Forgiveness* After Silence Broken Limbs DIRT! The Movie A Fragile Trust After Tiller Brother Towns Dirty Business Frankensteer After Winter, Spring The Buffalo War DIVEST! The Friendship Village The Age of Stupid Build Green Divide In Concord From Chechnya to Chernobyl The Allergy Fix Bully Dance Downwind/Downstream From The Ground Up America’s Lost Landscape Burning in the Sun A Dream In Hanoi Future Food* American Outrage Busting Out Drones In My Backyard Gaia The American Ruling Class Butterflies and Bulldozers Drowned Out Galileo’s Sons Another World is Possible Buyer Be Fair Early Life* Game Over: Conservation in Anthropocene Can Condoms Kill? Early Life 2* Kenya The Antibiotic Hunters Chasing Water East of Salinas Geologic Journey II* Argentina: Hope in Hard Times Chavez Ravine The Ecological -

Stuff Curriculum Guide, 2

Stuff Curriculum and Resource Guide Table of Contents Introduction Page View of Learning 3 Educational Approach Application A Sense of Hope Lessons and Activities 5 Module A: Introduction 5 A-1 Warm-up Quiz A-2 Your Weight in Stuff A-3 Stuff Presentation A-4 Begin Consumption Log A-5 Using Less A-6 For Better or Worse? A-7 Introduce Footprint Module B: Your Stuff 11 B-1 Report and Compare Consumption Logs B-2 Tracing Your Stuff B-3 Your Own Product Analysis B-4 Media and Advertising B-5 Space Mission Module C: Your School and Community’s Stuff 14 C-1 School Throughput C-2 Decision-Making Activity C-3 Made in… Stuff curriculum guide, 2 C-4 Alien Eyes Module D: More Stuff, Less Stuff 17 D-1 Oral History D-2 Other People’s Stuff D-3 Ways to Change D-4 Sustainable Wonders More Extension Activities 19 Extension 1 Design and Build Project Extension 2 Consumption Journal Extension 3 Focus on Wood Extension 4 Field Trips Glossary of Stuff Terms 20 Related Resources 21 Books Websites Consumerism General Environmental Education Media and Advertising Curriculum Packages Plays Tapes Songs Software British Colombia Curriculum Links 27 Unit Maps Assessment Portfolio Acknowledgments 30 Copyright 2000 Sightline Institute 2 Stuff curriculum guide, 3 Introduction This curriculum package was developed by NEW BC, a nonprofit organization based in Victoria, British Columbia, to accompany a 1997 book by Northwest Environment Watch (now Sightline Institute) called Stuff: The Secret Lives of Everyday Things. As an approach to science, social studies and environmental education, this material has a simple premise: that young people are curious about their world. -

"Living Sustainably; Creating Ecosociology"

WORKtNG DRAFT OF "Living Sustainably; Creating EcoSociology" by William F. Tarman-Ramcheck, Ph.D. _Principle Author And ~- Richard Coon, Ph.D. Technical Contributor Carroll College Waukesha, Wisconsin Spring, 2002 PREFACE for Archived and Electronically Preserved Documents By William F. Tarman-Ramcheck, December 12, 2012 (a.k.a. William F. Brugger from approximately 1962-1990, and William F. Ramcheck from 1952-1962) I, Bill Tarman-Ramcheck, do hereby make the following original authored documents and supporting research available to the "Sociology Of Sustainability" (SOS) program at Carroll University, and for others who may wish to learn more about them especially regarding the origins and framework for "Ecosociology." These are through my roles now as Adjunct faculty at Carroll University, "Sustainability Program Consultant" for Carroll, and former graduate of Carroll (in 1974 as Bill Brugger at Carroll College). The following archived and electronically preserved items are integral to the framework for the SOS program as a new Emphasis in the Sociology Major and Minor, and are all separate documents. They were the first known at the time to propose "Ecosociology" as a new "multi-discipline" combining Sociology with Ecology that subsumed many other disciplines as described in detail in the first document below. I proposed that "Ecosociology" framework in 1982 to potentially resolve the "Dunlap-Butte/ debates," which are still being referred to today as ongoing. For more on that see especially Jean-Guy Vaillancourt's "From environmental sociology to global ecosociology: the Dunlap-Butte/ debates" in The International Hand book of En vironmental Socio logy, Second Edition (Redclift and Woodgate, 2010). -

Escape from Affluenza Takes You Live to Watch the Joneses Announce Their Surrender

Related Bullfrog Films Titles: Affluenza 56 min. (in 2 parts for classroom use) With Study Guide Grades 6 - College VHS Purchase $250 Affluenza uses personal stories, expert commentary, hilarious old film clips, and “uncommercial” breaks to illuminate a serious social disease. With the help of historians and archival film, Affluenza reveals the forces that have dramatically transformed us from a nation that prized thriftiness - with strong beliefs in “plain living and high thinking” - into the ultimate consumer society. All The Right Stuff A 56 minute video 25 min. Grades 4-12 $195 In 2 parts for classrooms- 30/26 minutes With poor job prospects and little access to the political Produced and Written by John de Graaf & Vivia Boe process, teenagers come to see themselves as consumers. A co-production of John de Graaf and KCTS Seattle It’s a self-image marketers are only too happy to encour- age and exploit. The position of youth in our consumer economy is explored in this hip-hop style documentary. An excellent resource to teach young consumers about advertising, consumerism, and marketing. Teacher’s Guide — This Just In! — The infamous Jones family, the one we’ve all been trying to keep up with for years, is finally calling it quits. Escape from Affluenza takes you live to watch the Joneses announce their surrender. Contents (c) Did you feel like you had enough money to work with? 3 Be A Waste Reducer! (d) What are some ways to save money? 4 Activity #1 Calculating Solid Waste Production (e) Do you want a credit card ? What are the 5 Know -

Films for Use in Work-Family Courses

Films for Use in Work-Family Courses Authors: Morgan Sharoff and Stephen Sweet Source: The following films are abstracted from Sweet, S., Pitt-Catsouphes, M. (2006). Teaching work and family: Strategies, activities, and syllabi. Washington, DC: American Sociological Association, and syllabi posted on the Sloan Work and Family Network (http://wfnetwork.bc.edu/). Description: The films listed below have been shown in work-family courses. 9 to 5 No Longer (2008) – PBS Home Video “A demographic change is affecting all Americans wherever they work and live: the rise of the flexible workforce. The global economy, increasing numbers of two-income families and the need for businesses to retain talent both in the executive suite and among low-paid workers are all having an impact on the way we work. This documentary, hosted by Bonnie Erbe, explores the latest innovations in workplace flexibility.” -Abstract Affluenza (1997) - by John De Graaf (KTCS Seatle and Oregon Public Broadcasting) "A one-hour television special that explores the high social and environmental costs of materialism and overconsumption." (Lonnie Golden, from Syllabus) Brats: Growing Up Military (An Intimate Portrait of a Lost American Tribe) (2004) - by Donna Musil (Brats Productions, Inc./ Image FIlm & Video Center) "BRATS: Growing Up Military is the first feature-length documentary about a hidden American subculture - a lost tribe of over 4 million children from widely diverse backgrounds, raised on military bases around the world, whose shared experiences have shaped their lives so powerfully, they are forever different from their fellow Americans." (review from http://www.tckworld.com/thebratsfilm - For more information, visit the site) Chain of Love (2001) - by Marije Meerman (First Run/Icarus Films) A film about the Philippines' second largest export product - maternal love - and how this export affects the women involved, their families in the Philippines, and families in the West. -

Green Quad Learning Center for Sustainable

GREEN QUAD LEARNING CENTER FOR SUSTAINABLE FUTURES PRELIMINARY 2010 PERFORMANCE BLUEPRINT MARCH 15, 2010 MISSION STATEMENT The mission of the Learning Center for Sustainable Futures is to promote collaborative relationships among students, faculty, staff, and community members for exploring the changes required to create a sustainable society. STRATEGIC GOALS Goal #1: Promote student engagement in campus life on issues related to sustainability and the environment. Goal #2: Facilitate student success by serving as a gateway for involvement with faculty, staff, and members of local, statewide, and national organizations. Goal #3: Create a nationally-recognized program in the Green Quad through research, development, outreach, and assessment. - 1 - Goal #1: Promote student engagement in campus life on issues related to sustainability and the environment. [Link to SAAS Goal #1: Teaching and Learning] ANALYSIS: We are making substantial progress toward this goal. We are achieving most KPIs related to student engagement: providing a central source of information, working more extensively with Hall Government and the Resident Mentors, coordinating the efforts of RHA Sustainability-Reps, providing support for a model recycling program, and using the garden as a teaching tool. We are achieving most KPIs related to facilitating student organizations: offering training programs and providing logistical support. We are achieving most KPIs related to the Green Learning Community: supporting self-initiated programs and creating a strong sense of community. We are achieving most KPIs related to student engagement: promoting internships and service learning related to sustainability. And we are achieving most KPIs related to building an overall sense of community: promoting “green holidays” and other opportunities for students, faculty, staff, and community members to gather together. -

Anti-Globalization Movement - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Page 1 of 13 Anti-Globalization Movement

Anti-globalization movement - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Page 1 of 13 Anti-globalization movement From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The anti-globalization movement is critical of the globalization of capitalism. The Anti-consumerism movement is also commonly referred to as the global justice movement[1], alter- globalization movement, anti-corporate globalization movement[2], or movement against neoliberal globalization. Corresponding terms in other languages are mouvement altermondialiste[3] (French), globalisierungskritische Bewegung (German), or Movimento no-global (Italian). Participants base their criticisms on a number of related ideas.[4] What is shared is that participants stand in opposition to the unregulated political power of large, multi-national corporations and to the powers exercised through trade agreements Ideas and theory and deregulated financial markets. Specifically, corporations are accused of seeking Society of the Spectacle · to maximize profit at the expense of sabotaging work safety conditions and Culture jamming · standards, labor hiring and compensation standards, environmental conservation Corporate crime · Media principles, and the integrity of national legislative authority, independence and bias · Buy Nothing Day · Alternative culture · sovereignty. Recent developments, seen as unprecedented changes in the global Simple living · Do it economy, have been characterized as "turbo-capitalism" (Edward Luttwak), "market yourself · fundamentalism" (George Soros), "casino capitalism" (Susan Strange),[5] -

Principles Ofmicroeconomics Beon 101-02, Spring 2009 2:50 Pm on Mondays & Thursdays and Alt-1 Wednesdays at 2:15

Principles ofMicroeconomics Beon 101-02, Spring 2009 2:50 pm on Mondays & Thursdays and Alt-1 Wednesdays at 2:15 Professor Julie Matthaei Office Hours: Economics Department Mon. 9:30-10:30; Thurs. Wellesley College after class (4-5 pm), PNE 423, x2181 & by appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION:· OVERVIEW: This course is a survey ofmicroeconomics. Microeconomics focuses on the activities ofhouseholds and finns, in contrast to macroeconomics, which focuses on the economy as a whole. Studying microeconomics can give us perspective on our own economic decisions, as well as infonn us as citizens about important political economic issues, including microeconomic policy. The course structure is straightforward. After a briefintroductory section, we will study the simple supply and demand model, and then look at the economic behavior ofindividuals and households in consumption and in labor markets. Then we will focus on firms. The final section will study problems with the market economy, and reasons for and forms of government intervention in markets. STUDYING MULTPLE MICROECONOlVIIC THEORIES: This section will survey a broader range ofmicroeconomic theories than other sections do. While theories which are currently in the mainstream ofeconomics will be at the center ofour study together, and will be studied fully using a traditional textbook, we will also study some nontraditional theories. To accommodate this breadth, this course meets on alternative Wednesdays as well. Students who want an exclusively mainstream approach should consider changing sections. FOCUS ON ECONOMIC PROBLEMS AND TRANSFORMATION: This section will take as a basic assumption that, in spite of its many benefits and achievements, such as individual freedom ofchoice, growing equality ofeconomic opportunity for women and people of color, and technological innovation, our economic system also has serious problems, including climate change, persistent poverty and economic inequality, and excessive materialism and alienation.