DDG Evaluation Final Report Approved

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HEREFORD and WORCESTER – March 2020 See England, Shropshire and Staffordshire

HEREFORD and WORCESTER – March 2020 see England, Shropshire and Staffordshire Wyre Forest Family mountain bike trail www.forestryengland.uk/wyre-forest for details (3/20) The Three Rivers Ride www.breconbeacons.org/all_downloads/three-rivers-ride-leaflet.pdf to download (3/20) Walking and Cycling on the Malvern Hills Map and Guide FREE (2018) www.malvernhills.org.uk/visiting/cycling/ to download/obtain (3/20) Herefordshire Cider Cycling Routes: Ledbury (2003) £1 The Malverns Offroad Cycling Maps: £2.99 each Map 1 – East, 6 circular routes on bridleways and quiet lanes to the east of the Malvern Hills Map 2 – West, 8 circular routes on bridleways and quiet lanes to the north & west of the Malvern Hills Ledbury Walking & Cycling Map FREE (2005) The Ledbury Loop, a 17 ml rural cycle ride exploring the area’s cultural heritage £1 (2002) The Bosbury & Beyond Cycling Map, 3 routes £1 The Masefield Trail Cycling Map £1 The Newent Cycling Loop FREE By Bike in the Foothills of the Malverns, 4 rides exploring the Malvern Hills AONB £1.99 (2007) Herefordshire Leisure Cycling Guide, 6 leisure cycle routes around the county 5/30 mls FREE (2007) Forest of Dean Recreation Map £2.99 www.comecyclingledbury.com/bike-maps.html to download &/or order (3/20) Worcester Cycle Routes Worcestershire Cycling Guides www.worcestershire.gov.uk/info/20209/cycling/1416/worcestershire_cycle_routes to download (3/20) Towers & Spires Worcester, a cycling tour of churches around Worcester FREE (2015) http://cofeworcester.contentfiles.net/media/assets/file/15.07.02_Corrected_Diocese_of_Worcs_Church_Trails_LR.pdf to download Available from churches along the route & local TIC's (3/20) Teme Valley Trail Guide, 6 cycling routes www.visitthemalverns.org/things-to-do/walking/teme-valley-trail/ for details (3/20) . -

Adelheilige, 88–89, 95 Adolescence, Adolescentia: Definition Of

INDEX Adelheilige, 88–89, 95 ceramic vessels, 41–49 adolescence, adolescentia: defi nition child, childhood: accidents during, of, 127–134, 151–53; employment 112–14; constructions of, 37, during, 156–58; male, 128, 130–31, 89; education during, 92, 224; 157–72 employment during, 23, 104–04, 127, ageism, 234–37 157; esteem for, 70–71; initiation of, age of responsibility, 136–49 42–50, 129–130; prodigy, 93–96; ages of man, 3, 129, 152, 229–31; status of, 21, 24, 61, 66–68, 80–82; cohorts, 247–49; see cildhad, cnihthad, unbaptised, 32–33, 62–63. See also fulfremeda wæstm, geogoð, and yld cildhad, fosterage, pueritia Alfræði Íslenzk, 230 Christianity, 18–20, 31–48, 61–67, 87, Alfred, king of Wessex, 222 216, 229, 236 Alþingi, 82, 95, 132, 152, 159, 267, chronological age, 4–5, 110, 129–30, 295–96 134–37, 244–50, 261, 271–83 Andreas. See under Old English poetry cildhad, 207, 212. See also childhood, Athelstan/Aðelsteinn, king of England, pueritia 61 cnihthad, 207, 212. See also adolescence, Árni Þorláksson, bishop of Iceland, 88 adolescentia Ælfric, Homilies, 33–34; ‘Parable of the cognitive age, 4, 209; cognitive Vineyard’, 206–08 development, 207–13, 288–95 baptism, 32–33, 61–64 Denmark, 247 barn, 109–10, 231 Deor. See under Old English poetry Beowulf. See under Old English poetry dependency, 10, 52–53: in old age, biological/sexual age, 4–5, 23, 110, 239–42, 249–50, 252–54, 262–63, 143–45, 207–08, 231–34, 243–45, 298–300; úmætr/ómagar, 232–33, 249, 256–57, 261 252, 263; veizlusveinn, 82 bishops, 87–126: childhoods of, 12, disability, 29–36, 50–53, 107, 232 91–102; deaths of, 272–77; miracles Durham Proverbs. -

Guide to 20Th-Century Non- Domestic Buildings and Public Places In

th Guide to 20 -century Non- Domestic Buildings and Public Places in Worcestershire Published 2020 as part of NHPP7644 Adding a new layer: th 20 -century non-domestic buildings and public places in Worcestershire Authorship and Copyright: This guidance has been written by Emily Hathaway of Worcestershire County Council Archive and Archaeology Service and Jeremy Lake, Heritage Consultant with contributions by Paul Collins, Conservation Officer, Worcester City Council Published: Worcestershire County Council and Historic England 2020 Front Cover Image: Pre-fabricated Village Hall, Pensax. Images: © Worcestershire County Council unless specified. Publication impeded until October 2020, due to the impact of the COVID-19 global pandemic. NHPP7644: GUIDE TO 20th CENTURY NON-DOMESTIC BUILDINGS AND PUBLIC PLACES IN WORCESTERSHIRE CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………………………………………………1 1.1 The planning and legislative background…………………………………………………………..2 1.2 Heritage assets and Historic Environment Records…..……………………………………….3 2. TYPES OF 20TH CENTURY HERITAGE IN WORCESTERSHIRE………………………………………4 2.1 Agricultural and Subsistence (including Allotments) …………………………..………………4 2.2 Civil…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..11 2.3 Commemorative (including Public Art).…………………………………………………………….19 2.4 Commercial……………………………………………………………………………………………………….23 2.5 Communications……………………………………………………………………………………………….31 2.6 Defence…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….36 2.7 Education………………………………………………………………………………………………………….41 2.8 Gardens, Parks and -

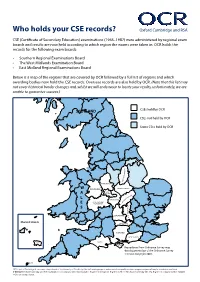

Who Holds Your CSE Records? Oxford Cambridge and RSA

Who holds your CSE records? Oxford Cambridge and RSA CSE (Certificate of Secondary Education) examinations (1965–1987) were administered by regional exam boards and results are now held according to which region the exams were taken in. OCR holds the records for the following exam boards: • Southern Regional Examinations Board • The West Midlands Examination Board • East Midland Regional Examinations Board Below is a map of the regions that are covered by OCR followed by a full list of regions and which awarding bodies now hold the CSE records. Overseas records are also held by OCR. (Note that this list may not cover historical border changes and, whilst we will endeavour to locate your results, unfortunately, we are unable to guarantee success.) SCOTLAND CSEs held by OCR CSEs not held by OCR Some CSEs held by OCR E R I H S M A H G N I T T O N STAFFORDSHIRE W SHROPSHIRE LEICESTERSHIRE WEST A MIDLANDS RE HI NS TO L P M WARWICKSHIRE A H T R HEREFORD AND O E WORCESTER N E R I S H S M A H G N I K OXFORDSHIRE C U B Channel Islands BERKSHIRE Guernsey HAMPSHIRE WEST SUSSEX Jersey DORSET ISLE OF WIGHT Reproduced from Ordnance Survey map data by permission of the Ordnance Survey © Crown copyright 2001. ISLES OF SCILLY OCR is part of Cambridge Assessment, a department of the University of Cambridge. For staff training purposes and as part of our quality assurance programme your call may be recorded or monitored. © OCR 2016 Oxford Cambridge and RSA Examinations is a Company Limited by Guarantee. -

Display PDF in Separate

PARTNERSHIP IN ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION SCHEMES IN THE MIDLAND REGION 1995 - 1996 Qctober 1996 INDEX / PAGE Introduction........................... 1 Upper Severn ..................... 2 Lower Severn ..................... 9 Upper Trent ..........................13 Lower Trent ..................... 17 Abbreviations ..................... ..20 Environment Agency Information Centre t f t PARTNERSHIP IN ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION. Introduction The Environment Agency’s principal aim is to "protect or enhance the environment, taken as a whole and to contribute toward achieving sustainable development." It cannot do this on its own. The Agency needs to develop appropriate relationships, such as partnerships and voluntary agreements, with all other sectors in the wider Community to work toward this end. The predecessor bodies of the Agency, the National Rivers Authority, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Pollution, Waste Regulation Authorities and some parts of the Department o f the Environment have all engaged previously in a variety of activities with different organisations to the benefit of the environment. This will continue. The Portfolio is a collation of some of the "Partnership" arrangements that have been used to protect or enhance the environment and shows how the "Partnership in Environment Protection" initiative can be taken forward. ■’ ■ i Partnerships are applicable in all kinds of situations,j in all places and necessary if sustainable solutions are to be found to the many environmental problems with'which.the Agency and other Organisations are concerned. The Environment Agency’s work is divided into eight main functions: Flood Defence," Water Resources, Pollution Control, Waste Regulation, Fisheries, Navigation, Recreation and Conservation. This range of statutory functions provides scope for "added value" schemes, the Agency takes advantage of this opportunity and develops projects with the various sectors within the Community! to the benefit of the environment. -

CRMP Arrangement of Fire Engines

Hereford & Worcester Fire Authority ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 2 COMMUNITY RISK MANAGEMENT PLAN 2014-2020 Contents Welcome and Introduction 5 Tackling the financial pressures ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Making the changes needed .................................................................................................................................................... 7 Planning for the future ............................................................................................................................................................. 8 How the Plan is Organised 9 A note on the style of this Plan ............................................................................................................................................. 10 The Authority and the Service ............................................................................................................................................... 11 1 Underlying Issues 14 The national focus .................................................................................................................................................................. 14 About our two counties ......................................................................................................................................................... -

Future Control Room Improvement Government Update on Fire and Rescue Authority Scheme

Future Control Room Improvement Future Control Room Improvement Government update on fire and rescue authority scheme November 2016 1 Future Control Room Improvement © Crown copyright 2016 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications 2 Future Control Room Improvement Contents Government update on fire and rescue authority scheme 1 Document purpose 5 FiReControl 5 The Future Control Room Services Scheme 5 Summary Assessment 7 Project completion and progress 7 The project partnerships 8 Coverage that will be provided as the Control Room Projects complete 9 Delivery of the resilience benefits 10 Financial Benefits 11 Comparing the benefits to FiReControl - Resilience of the system now 12 Locally delivered projects helping to secure national resilience 13 Delivery arrangements 16 The remaining projects 16 Next steps 17 Analysis 19 Timescales for completing the improvements 19 How the timescales for completing the improvements compare with the summary of March 2012 21 Planned resilience improvements 21 Progress against the October 2009 baseline towards completion -

HEREFORD and WORCESTER – September 2021 See England, Shropshire and Staffordshire

HEREFORD and WORCESTER – September 2021 see England, Shropshire and Staffordshire Wyre Forest Family mountain bike trail www.forestryengland.uk/wyre-forest for details (9/21) The Three Rivers Ride (horse route) www.bhsaccess.org.uk/dobbin/Ridingmap.php?map=westmidlands/Ridemaps/Threeriversride for details (9/21) Walking and Cycling on the Malvern Hills Map and Guide FREE (2018) www.malvernhills.org.uk/visiting/cycling/ to download/obtain (9/21) Herefordshire Cider Cycling Routes: Ledbury (2003) £1 The Malverns Offroad Cycling Maps: £2.99 each Map 1 – East, 6 circular routes on bridleways and quiet lanes to the east of the Malvern Hills Map 2 – West, 8 circular routes on bridleways and quiet lanes to the north & west of the Malvern Hills Ledbury Walking & Cycling Map FREE (2005) The Ledbury Loop, a 17 ml rural cycle ride exploring the area’s cultural heritage £1 (2002) The Bosbury & Beyond Cycling Map, 3 routes £1 The Masefield Trail Cycling Map £1 The Newent Cycling Loop FREE By Bike in the Foothills of the Malverns, 4 rides exploring the Malvern Hills AONB £1.99 (2007) Forest of Dean Recreation Map £2.99 www.comecyclingledbury.com/bike-maps.html to download &/or order (9/21) Herefordshire Walking & Cycling Maps, includes Hereford, Ledbury, Leominster and Leisure Rides www.herefordshire.gov.uk/downloads/download/214/herefordshire_walks_and_cycling_maps to download (9/21) Worcester Cycle Routes Worcestershire Cycling Guides www.worcestershire.gov.uk/info/20209/cycling/1416/worcestershire_cycle_routes to download (9/21) Towers & Spires Worcester, a cycling tour of churches around Worcester FREE (2015) https://temevalleynorthparish.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/15_07_02_Corrected_Diocese_of_Worcs_Church_Trails_LR.pdf to download. -

Report of the Hereford & Worcester Fire and Rescue Authority to the Herefordshire Council 1.The Chief Fire Officer's Servi

REPORT OF THE HEREFORD & WORCESTER FIRE AND RESCUE AUTHORITY TO THE HEREFORDSHIRE COUNCIL 1. THE CHIEF FIRE OFFIC ER’S SERVICE REPORT Performance Report The performance data for quarter 3 2010/11 reflected the exceptionally cold weather experienced in December 2010. The Chief Fire Officer told the Authority that during the period 19 – 31 December the Service responded to 463 incidents compared with 275 and 264 during the same period in 2009 and 2008 respectively. The Service instigated the Severe Weather Protocol on 19 December as attendances at incidents were effected by the dangerous conditions. The Authority agreed to record its thanks to the firefighters for their work on behalf of the community during the spell of severe weather conditions There was a 3% decrease in the total number of fires in the Quarter compared with Q3 last year (516 this quarter, compared to 532), despite a 28% increase in the number of chimney fires, which was thought to be weather-related and arising from the type of burners, the materials being burnt and the rural nature of the area covered by the Service. There was a 24% drop in the number of Road Traffic Collisions attended by the Service compared to Q3 09/10, down to 178 incidents from 234. Major Fire in Hereford City Centre In the early hours of Thursday 21 October 2010, fire crews from across Herefordshire and Worce stershire attended a serious fire in Hereford City Centre. The fire was particularly difficult and resource intensive to deal with due to it being fully developed on arrival and also the tightly packed and complicated building structures encountered by the initial crews attending. -

Pay Per Event Stand Prices for Providers, Charities, and Professional Bodies

Pay per event stand prices for providers, charities, and professional bodies UCAS 2019 higher education exhibitions, including Scottish events Premium shell scheme exhibitions Shell scheme events 6m x 4m shell 6m x 4m Single 3m x 2m Double 6m x 2m (4m shell back wall) space only 2019 Birmingham (NEC) £2,620 £3,950 £4,420 £5,140 London (ExCeL) £2,620 £3,950 £4,420 £5,140 Manchester (MCCC) £2,620 £3,950 £4,420 £5,140 All prices plus VAT. Shell scheme exhibitions Shell scheme exhibitions 2019 Single stand Double stand 6m x 4m shell 6m x 4m space only 3m x 2m 6m x 2m (4m shell back wall) Bristol £2,230 £3,370 £3,840 £4,560 Cardiff £2,230 £3,370 £3,840 £4,560 Edinburgh £1,840 £2,790 £3,840 £4,560 Exeter £2,230 £3,370 £3,840 £4,560 Glasgow £1,840 £2,790 £3,840 £4,560 Kent £1,840 £2,790 £3,840 £4,560 Liverpool £2,230 £3,370 £3,840 £4,560 Northern Ireland £2,230 £3,370 £3,840 £4,560 Sheffield £2,230 £3,370 £3,840 £4,560 Sussex £1,840 £2,790 £3,840 £4,560 Tyneside £2,230 £3,370 £3,840 £4,560 All prices plus VAT. Campus exhibitions Single stand 2m x 1m Double stand 4m x 1m Campus exhibitions 2019 (space only) (space only) Bedfordshire £1,150 £2,300 Cambridgeshire £840 £1,680 Cornwall £840 £1,680 Dorset £840 £1,680 East London £1,050 £2,100 East Midlands £1,050 £2,100 Essex £1,050 £2,100 Hampshire £840 £1,680 Hereford and Worcester £1,050 £2,100 Humberside £840 £1,680 Lancashire £840 £1,680 Lincolnshire £840 £1,680 All prices plus VAT. -

Hereford Sixth Form College

The Marches and Worcestershire Area Review Final report November 2016 Contents Background 4 The needs of The Marches and Worcestershire area 5 Demographics and the economy 5 Patterns of employment and future growth 8 LEP priorities 8 Feedback from LEPs, employers, local authorities and students 9 The quantity and quality of current provision 10 Performance of schools at Key Stage 4 11 Schools with sixth-forms 11 The further education and sixth-form colleges 12 The current offer in the colleges 13 Quality of provision and financial sustainability of colleges 15 Higher education in further education 16 Provision for students with special educational needs and disability (SEND) and high needs 17 Apprenticeships and apprenticeship providers 17 Land based provision 18 The need for change 19 The key areas for change 19 Initial options raised during visits to colleges 20 Criteria for evaluating options and use of sector benchmarks 22 Assessment criteria 22 FE sector benchmarks 22 Recommendations agreed by the steering group 23 Hereford College of Arts, Hereford Sixth Form College and Herefordshire and Ludlow College 24 Hereford Sixth Form College 24 South Worcestershire College 25 Worcester Sixth Form College 25 Heart of Worcestershire College 26 North Shropshire College 26 2 Telford College of Arts and Technology and New College Telford 27 Shrewsbury College of Arts and Technology and Shrewsbury Sixth Form College 27 Conclusions from this review 29 Next steps 31 3 Background In July 2015, the government announced a rolling programme of around 40 local area reviews, to be completed by March 2017, covering all general further education colleges and sixth-form colleges in England. -

Cabinet 12 September 2013 Future Partnership Working with Hereford and Worcester Fire and Rescue Service

Item 14 Cabinet 12 September 2013 Future Partnership Working with Hereford and Worcester Fire and Rescue Service Recommendations 1) That Cabinet note the re-starting of the project with Hereford and Worcester Fire and Rescue Service. 2) That officers report back on progress in due course. 1.0 Introduction 1.1 In May 2013, the Department for Communities & Local Government (CLG) published the findings of the Review into Efficiencies and Operations of Fire and Rescue Authorities in England, by Sir Ken Knight CBE, QFSM, FIFireE, the recently retired Government Chief Fire and Rescue Adviser for England. This review was commissioned by the Fire Minister, Brandon Lewis MP, to review the ways in which fire and rescue authorities may deliver further efficiencies and operational improvements without reducing the quality of front-line services to the public. 1.2 Full copies of the Knight Review have been provided in the Group Rooms. In summary, the Review considered five broad areas, namely: • What is efficiency and how efficient is the delivery of fire and rescue services in England? • Deploying resources. • Collaborating for efficiency. • Driving efficiency. • What is the future for fire and rescue? 1.3 It is the first national fire and rescue service (FRS) related review for some years that specifically assesses the size and structure of fire and rescue services, rather than other recent reports that have, for example, considered other issues such as the role of services in the community or in regard to specific operational risks and developments. The Review highlights the significant improvements in key national performance trends, such as the very 14 F&R Cab 13.09.12 1 of 5 large decrease in fire deaths and injuries and the reductions in many types of fires due to proactive efforts by all FRS’s over the last decade.