Health Services and Outcomes Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

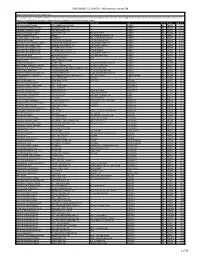

DISPENSING FEE REPORT - All Provinces Except ON

DISPENSING FEE REPORT - All provinces except ON Dispensing Fee Report January - March 2017 * In some provinces, a tiered fee schedule is in effect and thus some of the reported data may be skewed based upon such tiers. We strongly advise that you call the specific pharmacy of interest to ensure that you get the most updated, accurate fee information for the particular prescription that you require. Pharmacy Name Address(1) Address(2) City Prov. Postal Avg. Fee LOBLAW PHARMACY #4951 1050 YANKEE VALLEY ROAD AIRDRIE AB T4A2E4 $9.75 DRUGSTORE PHARMACY #1540 300 AIRDRIE ROAD NE AIRDRIE AB T4B3P2 $10.46 WALMART PHARMACY #1050 2881 MAIN STREET SW AIRDRIE AB T4B3G5 $11.78 SAFEWAY PHARMACY #8830 SOBEYS WEST INC. 505 MAIN STREET AIRDRIE AB T4B2B8 $11.88 SOBEYS PHARMACY #5172 AIRDRIE 100, 65 MACKENZIE WAY SW AIRDRIE AB T4B0V7 $11.98 POLARIS TRAVEL CLINIC AND PHARMACY 404-191 EDWARDS WAY SW AIRDRIE AB T4B3E2 $12.07 LONDON DRUGS #84 LONDON DRUGS LIMITED 110-2781 MAIN ST SW AIRDRIE AB T4B3S6 $12.10 SAVE-ON-FOODS PHARMACY #6602 OVERWAITEA PHARMACIES LTD 1400 MARKET STREET SE AIRDRIE AB T4A0K9 $12.22 SHOPPERS DRUG MART #2429 NARAYAN INVESTMENTS INC 2-804 MAIN STREET SE AIRDRIE AB T4B3M1 $12.25 SHOPPERS DRUG MART #2360 SELINGER DRUGGISTS LTD. 836 1ST AVE NW AIRDRIE AB T4B2R3 $12.26 SHOPPERS DRUG MART #2386 SELINGER DRUGGISTS LTD 310-505 MAIN ST AIRDRIE AB T4B3K3 $12.27 SHOPPERS DRUG MART #2328 WOLF PHARMACEUTICALS LTD 1200 MARKET STREET S.E. AIRDRIE AB T4A0K9 $12.28 PHARMASAVE #338 MELROSE DRUGS LTD. -

Drug Wars Sharon Mcleay Times Contributor

MARCH 22, 2013 Locally Owned & Operated STRATHMORE VOLUME 5 ISSUE 12 In a Rush? TIMESCALL LORNA PHIBBS Look for our Fresh Fruit 403-874-7660 106 - 304 - 3rd Ave., & Veggie Platters! Strathmore TO BUY OR SELL! [email protected] Ranch Market on the Trans Canada Hwy Associate Broker Page 11 Drug wars SHARON MCLEAY Times Contributor We are used to hearing about drug wars involv- ing illegal street drugs, but there is a war brewing over the Alberta government cuts made to legally Celebrating dispensed drugs by pharmacies. Pharmacists are St. Paddy’s Day saying the cuts will seriously affect the way they do business and will adversely affect client care. “They are sacrificing patient care. They are try- ing to look like they are saving money, but in Page 17 the long run they are sacrificing patient care. Es- pecially in rural areas, where in some cases, the pharmacy is your health care centre,” said Gord Morck, owner of Strathmore Value Drug Mart. An Alberta government review in 2008 deter- mined that generic drugs should be substituted for higher priced manufacturer brand name drugs to save money. They also determined that pharma- cists could charge 35 per cent over and above the manufacturer price to cover their staffing, busi- Spartans host ness, operations costs. The government then be- Provincials gan a yearly decrease on that percentage, leading to the present 18 per cent cost cut. Brand name drugs have no cost restrictions placed on them. “What they are doing is price controls. Some- Page 17 thing that I buy on April 29 that I pay $100 for; on May 1, I will have to sell for $50. -

TOWN of SYLVAN LAKE REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING AGENDA September 24, 20017:00 P.M

TOWN OF SYLVAN LAKE REGULAR COUNCIL MEETING AGENDA September 24, 20017:00 P.M. 1. Call to order 2. Minutes: Regular Council Meeting September 10, 2001 PUBLIC HEARINGSIDELEGATIONS 3. Public Hearing: Bylaw 1264/2001; Hewlett Park Stage 9; Pt ofNE y. 33-38-1-5; rezone from Urban Reserve (UR) to Narrow Lot General Residential District (R5). 4. Bylaw #1264/2001 (Planner comments available at meeting) PLANNING & DEVELOPMENT 5. Report from Development Officer re: Dale & Bonnie Ganske; Single Family Dwelling; 3232 - 50A Avenue (Lot 5, Block A, Plan 1365AB); Lakeshore Residential Direct Control District (LR-DC); (full plans available at meeting) 6. Nature's Health Clinic & More Ltd.: 4902-45 Avenue (Lots 21-24, Block C, Plan 7833AT); Inquiry re: Land Use Districting 7. Annexations: Red Deer County request for Intermunicipal Affairs Committee meeting and Annexation Negotiation Report 8. Report from MPC: 62 Unit Seniors Care Facility on Lot 2, BlockZ, Plan 922-2352 (4620-47 Avenue) 9. Report from MPC: Professional Building with Residential above on north part of Lot 34, Block A, Plan LXXXI (5036-48 Avenue); Retail and Commercial Service Direct Control District RECREATION & PARKS 10. Recreation Board Bylaw & Agreement with County; Director of Recreation S. Bames to provide verbal report. BYLAW ENFORCEMENT 11. Susan Quirico: correspondence regarding disturbances to residents located near Short Stop Foods Town ofSylvan Lake Regular Council Meeting Agenda September 24, 2001 Page 2 12. Alberta Solicitor General: Secondary Highway Enforcement WORKS & UTILITffiS 13. Speed Limit: Highway 20 south of47th Avenue ADMINISTRATION 14. Canada Municipal Policing Agreements: 2000101 Reconciliation; increase in Actual Costs 15. -

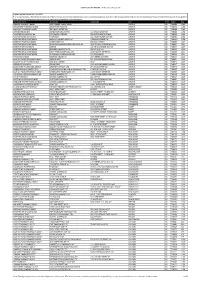

DISPENSING FEE REPORT - All Provinces Except ON

DISPENSING FEE REPORT - All Provinces Except ON Dispensing Fee Report Jan - Mar 2021 * In some provinces, a tiered fee schedule is in effect and thus some of the reported data may be skewed based upon such tiers. We strongly advise that you call the specific pharmacy of interest to ensure that you get the most updated, accurate fee information for the particular prescription that you require. Pharmacy Name Address(1) Address(2) City Prov. Postal Avg LOBLAW PHARMACY #4951 1050 YANKEE VALLEY ROAD AIRDRIE AB T4A2E4 11.48 DRUGSTORE PHARMACY #1540 300 AIRDRIE ROAD NE AIRDRIE AB T4B3P2 11.60 WALMART PHARMACY #1050 2881 MAIN STREET SW AIRDRIE AB T4B3G5 11.68 LONDON DRUGS #84 LONDON DRUGS LIMITED 110-2781 MAIN ST SW AIRDRIE AB T4B3S6 11.94 PHARMEDIC PHARMACY #4 FATIMA SERVICES INC 506-3 STONEGATE DR NW AIRDRIE AB T4B0N2 11.99 POLARIS TRAVEL CLINIC AND PHARMACY 404-191 EDWARDS WAY SW AIRDRIE AB T4B3E2 12.04 SHOPPERS DRUG MART #2429 NARAYAN INVESTMENTS INC 2-804 MAIN STREET SE AIRDRIE AB T4B3M1 12.06 SAFEWAY PHARMACY #8830 SOBEYS WEST INC. 505 MAIN STREET AIRDRIE AB T4B2B8 12.07 SHOPPERS DRUG MART #2431 GINCHER PHARMACEUTICAL SERVICES INC UNIT 801-401 COOPER BLVD SW AIRDRIE AB T4B4J3 12.07 SOBEYS PHARMACY #5172 AIRDRIE 100, 65 MACKENZIE WAY SW AIRDRIE AB T4B0V7 12.09 SHOPPERS DRUG MART #2360 SELINGER DRUGGISTS LTD. 836 1ST AVE NW AIRDRIE AB T4B2R3 12.10 SHOPPERS DRUG MART #2328 WOLF PHARMACEUTICALS LTD 1200 MARKET STREET S.E. AIRDRIE AB T4A0K9 12.11 SHOPPERS DRUG MART #2386 M. -

Office of the Information & Privacy Commissioner

Office of the Information & Privacy Commissioner OIPC Accepted Pharmacy PIA - Alberta Netcare Updated: May 15, 2017 Acceptance OIPC File # Store PIA Name Date (d/m/y) Contact H1448 Turtle Mountain Pharmacy Ltd. Alberta Netcare 15/12/2006 Darsey Milford H1484 Grandin Prescription Centre Inc. Alberta Netcare 12/01/2007 Mr. M. A. Stelmaschuk H1612 Winter's Pharmacy Alberta Netcare 07/05/2007 Ms. Jennifer Winter H1649 Nothern Lights I.D.A. Prescription Centre Alberta Netcare 29/06/2007 Ms. Erin Albrecht H1737 The Medicine Shoppe #153 - Brooks Alberta Netcare 13/09/2007 Ms. Monique Lavoie H1738 The Medicine Shoppe #109 - Peace River Alberta Netcare 13/09/2007 Ms. Monique Lavoie H1739 Hinton Hill Pharmacy Ltd. Alberta Netcare 13/09/2007 Ms. Monique Lavoie H1740 Anderson Drugs/The Medicine Shoppe #211 Alberta Netcare 13/09/2007 Ms. Monique Lavoie H1741 The Medicine Shoppe #184 - Barrhead Alberta Netcare 13/09/2007 Ms. Monique Lavoie H1744 Sexsmith Pharmacy Alberta Netcare 07/09/2007 Vishal Sharma H1880 Allin Pharmacy Alberta Netcare 08/01/2008 Mr. Adam Scott H1945 Health Select Pharmacy Alberta Netcare 05/02/2008 Mr. Farouk Haji H1958 Health Select Pharmacy Whitehorn Alberta Netcare 25/02/2008 Ms. Kristine Ewing H1971 Health Select Pharmacy Alberta Netcare 25/02/2008 Ms. Marlene Bykowski H2025 Medicine Shoppe Pharmacy #212 Alberta Netcare 14/04/2008 Mr. Warren Dobson H2041 Raymond Pharmacy Ltd. Alberta Netcare 02/07/2008 Mr. Wayne A. Smith H2042 Skelton’s Pharmacy Alberta Netcare 02/07/2008 Mr. Robert C. Clermont H2043 Mackenzie Drugs Alberta Netcare 02/07/2008 Ms. Lori Anheliger H2044 Gail’s Apothecary and Compounding Pharmacy Alberta Netcare 02/07/2008 Ms. -

Quarterly Disp Fee Rpt with DA COB Claims, ESC BOB Q4-2017- All Provinces Except Ontario Wdc EN.Xlsx

DISPENSING FEE REPORT - All Provinces Except ON Dispensing Fee Report Oct - Dec 2017 * In some provinces, a tiered fee schedule is in effect and thus some of the reported data may be skewed based upon such tiers. We strongly advise that you call the specific pharmacy of interest to ensure that you get the most updated, accurate fee information for the particular prescription that you require. Pharmacy Name Address(1) Address(2) City Prov. Postal Avg SAVE-ON-FOODS PHARMACY #6603 AIRDRIE WEST 601-401 COOPERS BLVD SW AIRDRIE AB T4B4J3 $5.05 SAVE-ON-FOODS PHARMACY #6602 OVERWAITEA PHARMACIES LTD 1400 MARKET STREET SE AIRDRIE AB T4A0K9 $5.43 LOBLAW PHARMACY #4951 1050 YANKEE VALLEY ROAD AIRDRIE AB T4A2E4 $11.63 DRUGSTORE PHARMACY #1540 300 AIRDRIE ROAD NE AIRDRIE AB T4B3P2 $11.68 WALMART PHARMACY #1050 2881 MAIN STREET SW AIRDRIE AB T4B3G5 $11.70 LONDON DRUGS #84 LONDON DRUGS LIMITED 110-2781 MAIN ST SW AIRDRIE AB T4B3S6 $12.01 SOBEYS PHARMACY #5172 AIRDRIE 100, 65 MACKENZIE WAY SW AIRDRIE AB T4B0V7 $12.07 SAFEWAY PHARMACY #8830 SOBEYS WEST INC. 505 MAIN STREET AIRDRIE AB T4B2B8 $12.07 POLARIS TRAVEL CLINIC AND PHARMACY 404-191 EDWARDS WAY SW AIRDRIE AB T4B3E2 $12.19 SHOPPERS DRUG MART #2386 SELINGER DRUGGISTS LTD 310-505 MAIN ST AIRDRIE AB T4B3K3 $12.25 SHOPPERS DRUG MART #2431 GINCHER PHARMACEUTICAL SERVICES INC UNIT 801-401 COOPER BLVD SW AIRDRIE AB T4B4J3 $12.26 SHOPPERS DRUG MART #2360 SELINGER DRUGGISTS LTD. 836 1ST AVE NW AIRDRIE AB T4B2R3 $12.28 SHOPPERS DRUG MART #2328 WOLF PHARMACEUTICALS LTD 1200 MARKET STREET S.E. -

Ostomy Supplies Vendors

Alberta Aids to Daily Living Program (AADL) - Alberta Health Ostomy Supplies Vendors AIRDRIE CREEKSIDE PHARMACY Phone: 403-945-0777 1113-403 MACKENZIE WAY SW Fax: 403-945-0555 AIRDRIE AB T4B 3V7 Toll Free: PHARMASAVE #338 Phone: 403-948-0010 101-209 CENTRE AVE SW Fax: 403-948-0011 AIRDRIE AB T4B 3L8 Toll Free: SHOPPERS DRUG MART #2386 Phone: 403-948-5858 302-505 MAIN ST Fax: 403-948-5651 AIRDRIE AB T4B 3K3 Toll Free: UNIVERSAL HEALTH PHARMACY #6 Phone: 403-980-7001 3-1861 MEADOWBROOK DR SE Fax: 403-980-7002 AIRDRIE AB T4A 1V3 Toll Free: ALIX ALIX DRUGS LTD. Phone: 403-747-2405 4904 50 AVE Fax: 403-747-2403 PO BOX 207 ALIX AB T0C 0B0 Toll Free: ATHABASCA ATHABASCA VALUE DRUG MART Phone: 780-675-2188 4911 50 ST Fax: 780-675-5777 ATHABASCA AB T9S 1E1 Toll Free: RX DRUG MART Phone: 780-675-2071 4923 50 ST Fax: 780-675-2585 ATHABASCA AB T9S 1E1 Toll Free: BANFF GOURLAY'S PHARMACY Phone: 403-762-2516 104-220 BEAR ST Fax: 403-762-8548 PO BOX 1080 BANFF AB T1L 1B1 Toll Free: RX DRUG MART Phone: 403-762-2245 317 BANFF AVE Fax: 403-762-8740 PO BOX 2620 BANFF AB T1L 1C3 Toll Free: © 2021 Government of Alberta July 9, 2021 This list is in constant flux due to ongoing revisions. For inquiries call (780) 422-5525 Page 1 of 23 Alberta Aids to Daily Living Program (AADL) - Alberta Health Ostomy Supplies Vendors BARRHEAD RITA'S APOTHECARY & HOME HEALTHCARE Phone: 780-674-6656 5036A 50 ST Fax: 780-674-3912 PO BOX 4561 BARRHEAD AB T7N 1A4 Toll Free: BASHAW PHARMASAVE BASHAW #319 Phone: 780-372-3503 5010 50 ST Fax: 780-372-3548 PO BOX 98 BASHAW AB T0B 0H0 Toll Free: BEAUMONT REXALL #7226 Phone: 780-929-8808 5910 50 ST NW Fax: 780-929-8809 BEAUMONT AB T4X 1T8 Toll Free: BEAVERLODGE REXALL #7507 Phone: 780-354-2088 1032 1 AVE Fax: 780-354-2350 PO BOX 600 BEAVERLODGE AB T0H 0C0 Toll Free: BEISEKER BEISEKER PHARMACY Phone: 403-947-3875 701 1 AVE Fax: 403-947-3777 PO BOX 470 BEISEKER AB T0M 0G0 Toll Free: BENTLEY BENTLEY IDA PHARMACY Phone: 403-748-3820 5018 50 AVE Fax: 403-748-2875 PO BOX 868 BENTLEY AB T0C 0J0 Toll Free: BERWYN BERWYN PHARMACY LTD. -

Pharmacies Carrying Community Based Naloxone Kits

Pharmacies carrying Community Based Naloxone kits Many pharmacies across Alberta can supply naloxone, a drug that can temporarily reverse a deadly fentanyl overdose and has been proven to save lives. Contact your pharmacy in advance to ensure availability. Below is a listing of pharmacies offering kits, current as of December 11th, 2018. This listing will be updated weekly or as changes are required. City Pharmacy Name Pharmacy Address Phone Hours of Operation Number North Zone Athabasca Loblaw Pharmacy #4904 #5007, 52 St. Athabasca, AB. 780-675- Mon to Fri: 9 a.m. - 6 a.m., Sat-Sun: 10 p.m. - 6 p.m. T9S 1V2 8410 Athabasca The Medicine Shoppe 2810B, 48 Ave. Athabasca, 780-675- Mon-Fri: 9 a.m. - 6 p.m., Stats: 12 a.m. - 4 p.m. Pharmacy #368 AB. T9S 0B1 3855 Athabasca Athabasca Value Drug Mart #4911, 50 St. Athabasca, AB. 780-675- Mon-Fri: 9 a.m. - 7 p.m., Sat: 9 a.m. - 6 p.m. T9S 1E1 2188 Barrhead Pembina West Co-op #4907, 49 St. Barrhead, AB. 780-674- Mon-Fri: 9 a.m. - 5:30 p.m. Pharmacy T7N 1A1 2201 Barrhead Rita's Apothecary & Home #5036A, 50 St. Barrhead, AB. 780-674- Mon-Fri: 9 a.m. - 9 p.m., Sat: 9 a.m. - 6 p.m., Sun: 10 Healthcare Ltd. T7N 1A4 6656 a.m. - 6 p.m. Beaverlodge Rexall Pharmacy #7507 #600, 1032 - 1 780-354- Mon-Fri: 8 a.m. - 6 p.m., Sat: 9 a.m. - 6 p.m. Ave. Beaverlodge, AB. T0H 2413 0C0 Berwyn Berwyn Pharmacy #5115, 51 St. -

Find a Pharmacy Near

Participating pharmacies in 2018 ENVIRx Program Pharmacy Address City Main Phone Apple Pharmacy 229 1 St SW Airdrie 587.775.5593 Calgary Co-Op Pharmacy #19 Sierra Springs 100-2700 Main St SE Airdrie 403.912.3703 Creekside Pharmacy 1113 - 403 Mackenzie Way SW Airdrie 403.945.0777 Drugstore Pharmacy #1540 300 Veteran's Blvd NE Airdrie 403.945.2335 Loblaw Pharmacy #4951 1050 Yankee Valley Rd Airdrie 403.912.3810 London Drugs #84 - Airdire 110 - 2781 Main St SW Airdrie 587.775.0336 Pharmasave #338 - Melrose Drugs 101 - 209 Centre Ave SW Airdrie 403.948.0010 Polaris Travel Clinic and Pharmacy 404 - 191 Edwards Way SW Airdrie 403.980.8747 Save-On-Foods Pharmacy #6602 - Airdire East 1400 Market St SE Airdrie 587.254.6570 Shoppers Drug Mart #2431 801-401 Coopers Blvd Airdrie 403.912.0246 Universal Health Pharmacy #6 - Airdrie 3-1861 Meadowbrook Dr SE Airdrie 403.980.7001 Guardian Beach Pharmacy 4925 50 Ave Alberta Beach 780.924.3647 Alix Drugs 4904 50 Ave Alix 403.747.2405 Athabasca Value Drug Mart 4911 50 St Athabasca 780.675.2188 Loblaw Pharmacy #4904 5007 52 St Athabasca 780.675.8410 Rx Drug Mart #2016 4923 50 St Athabasca 780.675.2071 Gourlay's Pharmacy 229 Bear St Banff 403.762.2516 Rx Drug Mart #2018 317 Banff Ave Banff 403.762.2245 Pembina West Co-Op Pharmacy 4907 49 St Barrhead 780.674.2201 Rita's Apothecary & Home Healthcare Ltd 5036A 50th St Barrhead 780.674.6656 Rx Drug Mart #2014 5028 50 St Barrhead 780.674.2121 Pharmasave Bashaw #319 5010 50 St Bashaw 780.372.3503 Loblaw Pharmacy #4009 5201 30 Ave Beaumont 780.929.2043 Rexall / Pharma -

2014-2015 Preceptors.Xlsx

The faculty and students within the Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of Alberta are very grateful to our preceptors. It is with great pride that we acknowledge their contributions to the development of future pharmacists in Alberta. In the past year, over 600 preceptors participated in the education of UofA Pharmacy students. Students traveled the province, visiting 54 communities, which included 195 community pharmacies and primary care networks. 67 Institutional sites exposed students to acute and long term care experiences, throughout the province. The following is a list of Clinical Placement Sites and Preceptors, August 2014 to August 2015 (*Preceptor of the Year Winners): The sites are listed according to where the placements occurred. Some of our preceptors have moved sites since the end of the placements. Airdrie Airdrie Rexall Drug Store # 7231 Khadra Baroud Polaris Travel Clinic and Pharmacy Jason Kmet Alix Alix Drugs IDA Trish Verveda Athabasca Athabasca Healthcare Centre Cindy Jones Banff Banff Mineral Springs Hospital Carol Vorster Gourlay's Pharmacy Peter Eshenko, Alma Steyn Black Diamond Oilfields General Hospital Darryl Forrester Blackfalds Sandstone Pharmacies ‐ Blackfalds Jennifer Fookes Blairmore Crowsnest Pass Health Centre Lisa Denie Bonnyville Bonnyville Health Centre Ginalyne Jabilona Pharmasave #325 Janelle Fox Tellier's Value Drug Mart Paul Tellier Calgary Alberta Children's Hospital Laura Bruno, Curtis Claassen, Heather Ganes, Dorinda Gonzales, Leela John, Jennifer Jupp, Richard Kaczowka, Angela Liang, Angela MacBride, Maryanne McDonald, Krista McKinnon, Meena Mehta, Michael Mills, Karen Ryan, Mandeep Wasson Blue Bottle Pharmacy Mark Percy Calgary Co‐op Pharmacy #6 Nadine Abou‐Kheir Calgary Coop Pharmacy #7 & #17 Ijenna Osakwe Calgary Co‐op #20 Dianne Lazorko‐Gamache Calgary Foothills Primary Care Network Kimberly Duggan, Mike Thompson, Amy Yu Calgary West Central Primary Care Network Penny Thomson Dr. -

2015 – 2016 Preceptors

2015 – 2016 Preceptors The faculty and students within the Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at the University of Alberta are very grateful to our preceptors. It is with great pride that we acknowledge their contributions to the development of future pharmacists in Alberta. In the past year, nearly 500 preceptors participated in the education of UofA Pharmacy students. Students traveled the province, visiting 50 communities, which included 145 community pharmacies and primary care networks. 60 Institutional sites exposed students to acute and long term care experiences, throughout the province. The following is a list of Clinical Placement Sites and Preceptors, August 2015 to August 2016 (*Preceptor of the Year Winners): The sites are listed according to where the placements occurred. Alix Trish Verveda Alix Drugs IDA Athabasca Jennifer McKinney Athabasca Healthcare Centre Banff Carol Vorster Banff Mineral Springs Hospital Peter Eshenko Gourlay's Pharmacy Barrhead Caitlin Clarke Rita's Apothecary & Home Healthcare Black Diamond Darryl Forester Oilfields General Hospital Bonnyville Ginalyne Jabilona Covenant Health Bonnyville Janelle Fox Pharmasave #325 Paul Tellier Tellier Pharmacy Bow Island *Taria Gouw Apple Drugs - Bow Island Brooks James Kitagawa Pharmasave #345 Calgary Ijenna Osakwe Calgary Coop Pharmacy #17 Academic Family Medicine Clinic - South Health Joe Tabler Campus/ Sheldon Chumir & Sunridge Centre Khadra Baroud Airdrie Rexall Drug Store # 7231 Kristen Blundell, Dorinda Gonzales, Jennifer Jupp, Alberta Children’s Hospital Timothy Kraft, Michelle Lam, Claudine Lanoue, Krista McKinnon, Brendon Mitchell, Jaimini Tailor, Yao Xue, Curtis Claassen, Trina Lycklama, Joni Shair Rebecca Chin Calgary Co-op Pharmacy #13 Matthew Fahlman Calgary Coop #9 Jennifer Lam, Betty Law, Calgary Foothills Primary Care Network Christelle Zacharki Calgary Mosaic Primary Care Network Marjorie Low Dr. -

Pharmacy Address City Phone

Pharmacies Participating in the 2020 ENVIRx Program Pharmacy Address City Phone Apple Pharmacy 229 1 St SW Airdrie (587) 775-5593 Calgary Co-Op Pharmacy #19 100-2700 Main St SE Airdrie (403) 912-3703 Creekside Pharmacy 1113-403 Mackenzie Way SW Airdrie (403) 945-0777 London Drugs #84 110-2781 Main St SW Airdrie (587) 775-0336 Melrose Drugs Ltd-Pharmasave #338 101-209 Centre Ave SW Airdrie (403) 948-0010 Midtown Pharmasave #363 202-1 Midtown Blvd SW Airdrie (403) 980-2598 Save-On-Foods Pharmacy #6602 1400 Market St SE Airdrie (587) 254-6570 Save-On-Foods Pharmacy #6603 - Airdrie West 601-401 Coopers Blvd SW Airdrie (587) 254-5810 The Medicine Shoppe Pharmacy #411 3-704 Main St SE Airdrie (403) 980-1587 Universal Health Pharmacy #6 - Airdrie 3-1861 Meadowbrook Dr SE Airdrie (403) 980-7001 101-4705 46A Ave Guardian Beach Pharmacy Box 307 Alberta Beach (780) 924-3647 PO Box 207 Alix Drugs 4904 50 Ave Alix (403) 747-2405 Andrew Pharmacy and Home Healthcare 5014 51 St Andrew (780) 365-3832 Athabasca Value Drug Mart 4911 50 St Athabasca (780) 675-2188 Rx Drug Mart #2016 4923 50 St Athabasca (780) 675-2071 PO Box 1080 Gourlay's Pharmacy 104-220 Bear St Banff (403) 762-2516 Rx Drug Mart #2018 317 Banff Ave Banff (403) 762-2245 Pembina West Co-op Pharmacy 4705 49 St Barrhead (780) 674-2201 PO Box 4561 Rita's Apothecary & Home Healthcare 5036A 50 St Barrhead (780) 674-6656 PO Box 4219 Rx Drug Mart #2014 5028 50 St Barrhead (780) 674-2121 Pharmasave Bashaw #319 5010 50 St Bashaw (780) 372-3503 Rexall #7226 5910 50 St NW Beaumont (780) 929-8808 Mint