You'll Find No Answers Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Evening with Alexis Rockman

Press Release Bruce Museum Presents Can Art Drive Change on Climate Change? An Evening with Alexis Rockman Acclaimed artist to be joined by David Abel, Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for The Boston Globe 6:30 – 8:30 pm, December 5, 2019 Bruce Museum, Greenwich, Connecticut Alexis Rockman, The Farm, 2000. Oil and acrylic on wood panel, 96 x 120 in. GREENWICH, CT, November 4, 2019 — On Thursday, December 5, 2019, Bruce Museum Presents poses the provocative question “Can Art Drive Change on Climate Change?” Leading the conversation is acclaimed artist and climate-change activist Alexis Rockman, who will present specially chosen examples of his work and discuss how, and why, he uses his art to sound the alarm about the impending global emergency. Adding insight and his own expert perspective is The Boston Globe’s David Abel, who since 1999 has reported on war in the Balkans, unrest in Latin America, national security issues in Washington D.C., and climate change and poverty in New England. Page 1 of 3 Press Release Abel was also part of the team that won the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News for the paper’s coverage of the Boston Marathon bombings. He now covers the environment for the Globe. Following Rockman’s presentation, Abel will join Rockman for a wide-ranging dialogue at the intersection of art and environmental activism, followed by question-and-answer session with the audience. Among the current generation of American artists profoundly motivated by nature and its future—from the specter of climate change to the implications of genetic engineering—Rockman holds an unparalleled place of honor. -

The Rhetorical Limits of Visualizing the Irreparable 1 - 7 Nature of Global Climate Change Richard D

Communication at the Intersection of Nature and Culture Proceedings of the Ninth Biennial Conference on Communication and the Environment Selected Papers from the Conference held at DePaul University, Chicago, IL, June 22-25, 2007 Editors: Barb Willard DePaul University Chris Green DePaul University Host: DePaul University, College of Communication Communication at the Intersection of Nature and Culture Proceedings of the Ninth Biennial Conference on Communication and the Environment DePaul University, Chicago, IL, June 22-25, 2007 Edited by: Barbara E. Willard Chris Green College of Communication Humanities Center DePaul University DePaul University Editorial Assistant: Joy Dinaro College of Communication DePaul University Arash Hosseini College of Communication DePaul University Publication Date: August 11, 2008 Publisher of Record: College of Communication, DePaul University, 2320 N. Kenmore Ave., Chicago, IL 60614 (773)325-2965 Communication at the Intersection of Nature and Culture: Proceedings of the Ninth Biennial Conference on Communication and the Environment Barb Willard and Chris Green, editors Table of Contents i - iv Conference Program vi-xii Preface and Acknowledgements xiii – xvi Twenty-Five Years After the Die is Cast: Mediating the Locus of the Irreparable From Awareness to Action: The Rhetorical Limits of Visualizing the Irreparable 1 - 7 Nature of Global Climate Change Richard D. Besel, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Love, Guilt and Reparation: Rethinking the Affective Dimensions of the Locus of the 8 - 13 Irreparable Renee Lertzman, Cardiff University, UK Producing, Marketing, Consuming & Becoming Meat: Discourse of the Meat at the Intersections of Nature and Culture Burgers, Breasts, and Hummers: Meat and Masculinity in Contemporary Television 14 – 24 Advertisements Richard A. -

Why Look at Dead Animals? Taxidermy in Contemporary Art by Vanessa Mae Bateman Submitted to OCAD University in Partial Fulfillme

Why Look at Dead Animals? Taxidermy in Contemporary Art by Vanessa Mae Bateman Submitted to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Contemporary Art, Design, and New Media Art Histories Vanessa Mae Bateman, May 2013 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. ! Copyright Notice This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. You are free to: Share – To copy, distribute and transmit the written work. You are not free to: Share any images used in this work under copyright unless noted as belonging to the public domain. Under the following conditions: Attribution – You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Noncommercial – You may not use those work for commercial purposes. Non-Derivative Works – You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. With the understanding that: Waiver — Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. Public Domain — Where the work or any of its elements is in the public domain under applicable law, that status is in no way affected by the license. -

M a R K D I O N 1961 Born in New Bedford, MA Currently Lives In

M A R K D I O N 1961 Born in New Bedford, MA Currently lives in Copake, NY and works worldwide Education, Awards and Residencies 1981-82, 86 University of Hartford School of Art, Hartford, CT, BFA 1982-84 School of Visual Arts, New York 1984-85 Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Independent Study Program 2001 9th Annual Larry Aldrich Foundation Award 2003 University of Hartford School of Art, Hartford, CT, Doctor of Arts, PhD 2005 Joan Mitchell Foundation Award 2008 Lucelia Award, Smithsonian Museum of American Art, Washington D.C. 2012 Artist Residency, Everglades, FL 2019 The Melancholy Museum, Cantor Arts Center, Stanford University, Stanford, CA Academic Fellowships 2015-16 Ruffin, Distinguished Scholar, Department of Studio Art, University of Virginia Charlottesville, VA 2014-15 The Christian A. Johnson Endeavor Foundation Visiting Artist in Residence at Colgate University Department of Art and Art History, Hamilton, NY 2014 Fellow in Public Humanities, Brown University, Providence 2011 Paula and Edwin Sidman Fellow in the Humanities and Arts, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI Solo Exhibitions (*denotes catalogue) 2020 The Perilous Texas Adventures of Mark Dion, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth* Mark Dion: Follies, Laumeier Sculpture Park, St. Louis, MO Mark Dion & David Brooks: The Great Bird Blind Debate, Planting Fields Foundation, Oyster Bay, NY Mark Dion & Dana Sherwood: The Pollinator Pavilion, Thomas Cole National Historic Site, Catskill, NY 2019 Wunderkammer 2, Esbjerg Museum of Art, Esbjerg, Denmark -

Subhankar Banerjee Resume

SUBHANKAR BANERJEE I was born in 1967 in Berhampore, a small town near Kolkata, India. My early experiences in my tropical home in rural Bengal fostered my life long interest in the value of land and it’s resources. In the cinemas of these small towns, I came to know the work of brilliant Bengali filmmakers including, Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, and Ritwik Ghatak. I loved cinema and found their visual explorations of everyday life and larger social issues immensely inspiring. I asked my Great Uncle Bimal Mookerjee, a painter, to teach me how to paint. I created portraits and detailed rural scenes, but knew from growing up in a middle-income family that it would be nearly impossible for me to pursue a career in the arts. I chose instead the practical path of studying engineering in India and later earned master’s degrees in physics and computer science at New Mexico State University. In the New Mexican Desert, I fell in love with the open spaces of the American West. I hiked and backpacked frequently in New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, and Utah, and bought a 35mm camera with which I began taking photographs. After finishing my graduate degrees in Physics and Computer Science, I moved to Seattle, Washington to take up a research job in the sciences. In the Pacific Northwest, my commitment to photography grew, and I photographed extensively during many outdoor trips in Washington, Oregon, Montana, Wyoming, California, New Hampshire, Vermont, Florida, British Columbia, Alberta, and Manitoba. In 2000, I decided to leave my scientific career behind and began a large-scale photography project in the American Arctic. -

FOLLIES COME to LAUMEIER Laumeier Sculpture Park Presents Mark Dion: Follies, February 15–May 24, 2020

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Jamie Vishwanat Marketing & Communications Manager 314-615-5277 [email protected] FOLLIES COME TO LAUMEIER At a Glance WHO: A solo exhibition of artwork by internationally acclaimed artist Mark Dion. WHAT: Mark Dion: Follies, an exhibition of five sculptures and one dozen works on paper that present the artist’s fantastical, architectural worlds. Related public programs help visitors explore the artwork’s themes. WHEN: The exhibition will be on view from February 15–May 24, 2020. Laumeier Sculpture Park is free and open daily from 8:00 a.m. until 30 minutes past sunset. WHERE: Laumeier Sculpture Park, 12580 Rott Road, St. Louis, MO 63127. The majority of the exhibition will be presented in the Whitaker Gallery in the Aronson Fine Arts Center, with two sculptures also presented in Laumeier’s Outdoor Galleries. WHY: Mark Dion is an accomplished, celebrated and world-renown artist whose work is embraced by the critics and the general public alike. His artwork explores the intersections between nature, science, architecture, and scholarship in ways that are intelligent, funny, dark, and thought provoking. This exhibition will introduce St. Louis audiences to a substantial amount of his work across multiple media (sculpture, installation, photographs, prints and drawings). Laumeier Sculpture Park presents Mark Dion: Follies, February 15–May 24, 2020 Laumeier Sculpture Park is proud to present Mark Dion: Follies. Mark Dion has fashioned a world-wide reputation as an innovative sculptor and installation artist whose points of departure include the intersections of the historical and the contemporary, as well as the man-made and natural worlds. -

Lari Pittman

LARI PITTMAN Born 1952 in Los Angeles Lives and works in Los Angeles EDUCATION 1974 BFA in Painting from California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, CA 1976 MFA in Painting from California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, CA SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 Lari Pittman: Dioramas, Lévy Gorvy, Paris 2020 Iris Shots: Opening and Closing, Gerhardsen Gerner, Oslo Lari Pittman: Found Buried, Lehman Maupin, New York 2019 Lari Pittman: Declaration of Independence, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles 2018 Portraits of Textiles & Portraits of Humans, Regen Projects, Los Angeles 2017 Lari Pittman, Gerhardsen Gerner, Oslo Lari Pittman / Silke Otto-Knapp: Subject, Predicate, Object, Regen Projects, Los Angeles 2016 Lari Pittman: Grisaille, Ethics & Knots (paintings with cataplasms), Gerhardsen Gerner, Berlin Lari Pittman: Mood Books, Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, CA Lari Pittman: Nocturnes, Thomas Dane Gallery, London Lari Pittman: NUEVOS CAPRICHOS, Gladstone Gallery, New York 2015 Lari Pittman: Homage to Natalia Goncharova… When the avant-garde and the folkloric kissed in public, Proxy Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design, Los Angeles 2014 Lari Pittman: Curiosities from a Late Western Impaerium, Gladstone Gallery, Brussels 2013 Lari Pittman: from a Late Western Impaerium, Regen Projects, Los Angeles Lari Pittman, Bernier Eliades Gallery, Athens Lari Pittman, Le Consortium, Dijon, France Lari Pittman: A Decorated Chronology, Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, MO 2012 Lari Pittman, Gerhardsen Gerner, Berlin thought-forms, -

L.E.S. Gallery Evening Thursday, November 19, 4-8 Pm

L.E.S. Gallery Evening Thursday, November 19, 4-8 pm This coming Thursday, over 40 galleries on the Lower East Side will be open later to celebrate current exhibitions throughout the neighborhood. An interactive map is available here. 1969 Gallery frosch&portmann Off Paradise 56 HENRY GRIMM Pablo’s Birthday Andrew Edlin Gallery Helena Anrather Perrotin Arsenal Contemporary Art New James Cohan Peter Freeman, Inc. York James Fuentes LLC Pierogi ASHES/ASHES Kai Matsumiya Rachel Uffner Gallery ATM gallery NYC Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery RICHARD TAITTINGER GALLERY Bridget Donahue Krause Gallery Sargent’s Daughters Bureau LICHTUNDFIRE Shin Gallery carriage trade Lubov SHRINE Cristin Tierney Gallery M 2 3 signs and symbols David Lewis Magenta Plains Simone Subal Gallery DEREK ELLER GALLERY MARC STRAUS GALLERY Sperone Westwater Equity Gallery Martos Gallery The Hole FIERMAN McKenzie Fine Art Thomas Nickles Project Foxy Production Miguel Abreu Gallery Tibor de Nagy Gallery Freight+Volume Nathalie Karg Gallery Ulterior Gallery Front Room Gallery No Gallery Zürcher Gallery 1969 Gallery http://www.1969gallery.com 103 Allen Street INTERIORS: hello from the living room Amanda Barker, Johnny DeFeo, Lois Dodd, Gabrielle Garland, JJ Manford, John McAllister, Quentin James McCaffrey, Gretchen Scherer, Adrienne Elise Tarver, Ann Toebbe, Sophie Treppendahl, Brandi Twilley, Anna Valdez, Darryl Westly, Guy Yanai and Aaron Zulpo November 1 – November 29 56 HENRY https://56henry.nyc/ 56 Henry Street Richard Tinkler / Seven Paintings October 15 - November 25, 2020 56 HENRY shows seven paintings by Richard Tinkler. As if seen through a kaleidoscope or under the spell of deep meditation, the works often begin with a shared process before iterative reimagining delivers each to a novel conclusion. -

Introducing Bruce Museum Presents: Thought Leaders in Art and Science

Press Release Introducing Bruce Museum Presents: Thought Leaders in Art and Science Film producer and art collector Jennifer Blei Stockman inaugurates the Bruce Museum Presents series with a moderated conversation between contemporary women artists on Thursday, September 5. GREENWICH, CT, August 1, 2019 — Bruce Museum Presents is an exciting new series of monthly public programs featuring thought leaders in the fields of art and science. Showcasing experts on compelling subjects of relevance and interest to members and visitors to the Bruce Museum, as well as the communities of greater Fairfield County and beyond, Bruce Museum Presents launches on Thursday, September 5, 2019 at 6:00 pm, with Generation ♀: How Contemporary Women Artists Are Re-Shaping Today’s Art World. Jennifer Blei Stockman, producer of the Emmy-nominated 2018 HBO documentary The Price of Everything, moderates a wide-ranging dialogue and exploration with four major contemporary women artists: painter and sculptor Nicole Eisenman; conceptual visual artist Lin Jingjing; painter and sculptor Paula DeLuccia Poons; and photographer and filmmaker Laurie Simmons. Page 1 of 5 Press Release Background “Bruce Museum Presents inaugurates an exciting time of change and progress for this institution,” said Robert Wolterstorff, The Susan E. Lynch Executive Director and Chief Executive Officer. “As we prepare our expansion in order to become the region’s leading cultural center, the Bruce Museum is poised to present dynamic and unique educational programming equal to the caliber of our new spaces and collections.” Suzanne Lio, Managing Director of the Bruce Museum, conceived Bruce Museum Presents. “We have long been an important resource in our community for forward-thinking public programs,” Lio notes. -

The Pit Lmarkus CV 2021

Liz Markus b. 1967, Buffalo, NY Lives in Los Angeles, CA Education BFA, School of Visual Arts, New York, NY MFA, Tyler School of Art, Philadelphia, PA Solo and Two-Person Exhibitions 2021 Kermit, Kantor Gallery, Los Angeles, CA T Rex, The Pit, Glendale, CA 2020 Super Disco Disco Breakin’, Unit London, London, UK 2018 The Palm Beach Paintings, County Gallery, Palm Beach, FL 2017 Maruani Mercier Gallery, Brussels, BE 2014 Town & Country, Nathalie Karg Gallery, New York, NY 2012 Eleven, Ille Arts, Amagansett, NY The Look of Love, ZieherSmith, New York, NY 2010 Are You Punk Or New Wave? ZieherSmith, New York, NY 2009 Hot Nights At The Regal Beagle, ZieherSmith, New York, NY 2007 What We Are We’re Going To Wail With On This Whole Trip, Loyal Gallery, Stockholm, SWE The More I Revolt, The More I Make Love, ZieherSmith, New York, NY 2000 White Columns, New York, NY Group Exhibitions 2020 NADA 2020, The Pit, Los Angeles Six Hot and Glassy, with Katherine Bernhardt, Ashley Bickerton, Katherine Bradford, Mary Heilmann,Liz Markus, Dan McCarthy, Raymond Pettibon, Alexis Rockman, Lucien Smith, and Keith Sonnier, Tripoli Gallery, East Hampton Riders of The Red Horse, The Pit, Los Angeles 36 Paintings, Harper’s Books, East Hampton, NY 2019 YES., organized by Terry R. Myers, Patrick Painter Inc., Los Angeles Go Figure!, curated by Beth DeWoody, Eric Firestone Gallery, East Hampton, NY 2018 Fuigo, curated by Laura Dvorkin and Maynard Monrow, Fuigo, New York 2017 Man Alive, Jablonka Maruani Mercier Gallery, Brussels, Belgium, curated by Wendy White 2015 -

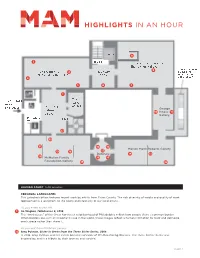

Highlights in an Hour

Bloomfield Avenue HIGHLIGHTS IN AN HOUR GALLERY LEVEL (2ND FLOOR) ELEVATOR 8 3 STAIR B Judy and Josh Weston Exhibition Gallery 9 The Blanche and Rand Gallery of 4 Elevator Irving Laurie Native American Art Lobby Foundation 2 Art Stairway 5 6 7 e u n e 1 v A n The i S.MOUNTAIN a t Store e n MUSEUM c a u at MAM Robert H. l o ENTRANCE GGeorgeeorge P M s Lehman Inness ’ h 10 Inness 11 e t Court k u Gallery Gallery u o L S Reception STAIR C . Desk t S 23 22 21 16 16 Marion Mann Roberts Gallery 15 McMullen Family F19oundati18on Gallery Rotunda Marion Mann Roberts Gallery Rotunda 14 13 20 McMullen Family 16 16 Foundation Gallery 17 12 PARKING LOT LEHMAN COURT 5-10 minutes PERSONAL LANDSCAPES This juried exhibition features recent work by artists from Essex County. The rich diversity of media and quality of work represented is a testament to the talent and creativity of our local artists. As you enter, to the left: 1 Ira Wagner, Twinhouses 3, 2018 The “twinhouses” of the Great Northeast neighborhood of Philadelphia reflect how people share a common border. When borders are such an important issue in the world, these images reflect a human inclination to mark and delineate one’s space rather than share it. As you exit from McMullen Gallery: 23 Amy Putman, Sister in Green from the Three Sister Series, 2018 In 2018, Amy Putman and her sisters became survivors of life-threatening illnesses. The Three Sisters Series was inspired by, and is a tribute to, their journey and survival. -

Future Shock and Sitelab : Kota Ezawa

SITE SANTA FE ANNOUNCES INAUGURAL EXHIBITIONS FOR NEW BUILDING OPENING FALL, 2017; NEW SITElab PROJECT SPACE Future Shock October 7, 2017-May 20, 2018 Kota Ezawa: The Crime of Art SITElab Project Space October 7, 2017 – January 10, 2018 Opening Events: October 5-8, 2017 Rafael Lozano-Hemmer in collaboration with Krzysztof Wodiczko, Zoom Pavilion, 2015 SITE Santa Fe, NM, June 20, 2017 – SITE Santa Fe will present Future Shock, a large- scale exhibition of international artists that articulates the profound impact of the acceleration of technological, social, and structural change upon contemporary life. This exhibition will mark the reopening of SITE Santa Fe to the public in a newly expanded building designed by SHoP Architects. Future Shock takes its title from Alvin Toffler’s prophetic 1970’s book, in which he describes the exhilaration and consequences of our rapidly advancing world. With Toffler’s predictions and warnings as a backdrop, Future Shock will bring together the work of 10 artists, including new commissions by Regina Silviera, Alexis Rockman, and Lynn Hershman Leeson, whose works imagine a range of visions of our present and future. The works in Future Shock will feature large-scale video, installation, painting, and sculpture which explore: the role of technology and science in society, the effects of financial markets and globalism, the impact of migration and population growth, and issues of surveillance and privacy. As exhibition curator and SITE’s Phillips Director and Chief Curator Irene Hofmann explains: “As we reintroduce SITE with the opening of a bold and expanded building this fall, we will present an exhibition that examines our dynamic and decisive moment in global history and looks to the challenges and possibilities of the future.” The work in the exhibition includes: Doug Aitken (US) Migration (2008), a large-scale video installation that explores the collision of humans and animals as the built environment sprawls .