The Fat Filly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pacific Wind Captures the G2 Ruffian at Belmont Park

PASSPORT Pacific Wind captures the G2 Ruffian at Belmont Park OVERVIEW G2 winner/G1Placed on the DIRT G2 placed on the TURF By leading sire CURLIN Half-Sister to multiple Graded Stakes Winner PACIFIC WIND HIP Curlin x Shag, by Dixieland Band 163 BARN 9 Selling Tuesday, November 5th PAST PERFORMANCES G1Ws G2Ws G1W GSP G2W G2W Pacific Wind put together an unforgettable debut performance winning by 4 ½ lengths (Replay) over a mile on the turf at Santa Anita and was anointed as a TDN ‘Rising Star’ for her efforts. Pacific Wind becomes a ‘Rising Star’ with a 4 ½ length, debut win at Santa Anita. She would earn graded blacktype in her next two races, finishing 3rd in both the G2 Honeymoon and the G3 Senorita, both over the TURF at Santa Anita. Later in her three-year-old season, she was tried on the dirt for the first time over 1 1/16 miles at Santa Anita and responded with a 1 ¾ lengths win (Replay), earning a then career best Beyer of 93, beating future G2W/G1P LA FORCE At four, she was sent east to the barn of Chad Brown, who brought her back in an allowance race at Keeneland over a mile on the dirt where she crushed her foes by 8 ¼ lengths (Replay), beating G1W SAILOR'S VALENTINE. Her (22) Thoro-Graph figure in this race matched the number that G1W SHE'S A JULIE earned when winning this year’s G1 La Troienne. Next out, she was sent off favored in the G2 Ruffian over a mile at Belmont Park, where she won by a length (Replay), defeating G2 winners HIGHWAY STAR, TEQUILITA, FAYPIEN and UNCHAINED MELODY. -

Tara Stud's Homecoming King

TUESDAY, 15 DECEMBER 2020 DEIRDRE TO VISIT GALILEO IN 2021 TARA STUD'S A new direction in the extraordinary odyssey of the Japanese HOMECOMING KING mare Deirdre (Jpn) (Harbinger {GB}BReizend {Jpn, by Special Week {Jpn}) began on Monday when the 6-year-old left her adopted home of Newmarket to begin her stud career in Ireland. Her first mating is planned to be with Coolmore's champion sire Galileo (Ire). Bred by Northern Farm and raced by Toji Morita, Deirdre's first three seasons of racing were restricted largely to Japan, where she won five races, including the G1 Shuka Sho. She also took third in the G1 Dubai Turf on her first start outside her native country. Following her return visit to the Dubai World Cup meeting in 2019, Deirdre travelled on to Hong Kong and then to Newmarket, which has subsequently remained her base for an ambitious international campaign. Cont. p6 River Boyne | Benoit photo IN TDN AMERICA TODAY VOLATILE SETTLING IN AT THREE CHIMNEYS By Emma Berry and Alayna Cullen GI Alfred G. Vanderbilt H. winner Volatile (Violence) is new to On part of its 70-mile journey across Ireland, the River Boyne Three Chimneys Farm in 2021. The TDN’s Katie Ritz caught up flows not far from Tara Stud in County Meath, but the stallion with Three Chimneys’ Tom Hamm regarding the new recruit. named in its honour has taken a far more meandering course Click or tap here to go straight to TDN America. simply to return to source. Approaching his sixth birthday, River Boyne (Ire) (Dandy Man {Ire}) is back home from America and about to embark on a stallion career five years after he was sold by his breeder Derek Iceton at the Goffs November Foal Sale. -

Horse Racing

Horse Racing From the publisher of: EQUUS Dressage Today Horse & Rider Practical Horseman Arabian Horse World Search Home :: Classifieds :: Shopping :: Forums/Chat :: Subscribe :: News & Results :: Giveaway Winners Newsletter Sign-Up Racing Win It! Weekly tips and articles Sponsor this topic! Win Reichert on horse care, training Celebration VIP Passes! and more >> Speed is of the essence in this sport that pits the fastest equines against each Growing Up With Horses other. Here, find stories on Thoroughbreds, Standardbreds and other racing Kids' Essay Contest TOPICS breeds. Enter JPC Equestrian's Home $10,000 Giveaway On the 30th Anniversary of About EquiSearch Win an Irish Riding Trip Art & Graphics Ruffian's Last Race & More! Associations Lyn Lifshin reflects on the life of the super racehorse Ruffian who died Breeds during a match race against Foolish Where To Shop! Horse Care Pleasure on July 6, 1975. Columnists Equestrian Collections Community The Superstore for Horse Equine Education and Rider EquiWire News/Results The Equine Collection Farm and Stable Horse books and DVDs Kentucky Horse Park Glossary Horsey Humor Horse Racing News & Results Gift Shop Junior Horse Lovers Gifts and Collectibles Find A Tack Shop Lifestyle More Racing Articles Magazines Shoemaker Remembered Beginning Adult Rider Buyers' Guides October 16, 2003 -- Bill Shoemaker died October 12 at Quiz the age of 72. His fellow jockeys share their memories. Insurance Rescue/Welfare Tack & Apparel Seabiscuit Trailers Shopping More Buyers' Guides Horse Sports Endurance Seabiscuit: An American Legend. Steeplechase News, photos, quotes and more on the Depression-era racing star and his Olympics connections. To visit EquiSearch's special section on Seabiscuit click here. -

MJC Media Guide

2021 MEDIA GUIDE 2021 PIMLICO/LAUREL MEDIA GUIDE Table of Contents Staff Directory & Bios . 2-4 Maryland Jockey Club History . 5-22 2020 In Review . 23-27 Trainers . 28-54 Jockeys . 55-74 Graded Stakes Races . 75-92 Maryland Million . 91-92 Credits Racing Dates Editor LAUREL PARK . January 1 - March 21 David Joseph LAUREL PARK . April 8 - May 2 Phil Janack PIMLICO . May 6 - May 31 LAUREL PARK . .. June 4 - August 22 Contributors Clayton Beck LAUREL PARK . .. September 10 - December 31 Photographs Jim McCue Special Events Jim Duley BLACK-EYED SUSAN DAY . Friday, May 14, 2021 Matt Ryb PREAKNESS DAY . Saturday, May 15, 2021 (Cover photo) MARYLAND MILLION DAY . Saturday, October 23, 2021 Racing dates are subject to change . Media Relations Contacts 301-725-0400 Statistics and charts provided by Equibase and The Daily David Joseph, x5461 Racing Form . Copyright © 2017 Vice President of Communications/Media reproduced with permission of copyright owners . Dave Rodman, Track Announcer x5530 Keith Feustle, Handicapper x5541 Jim McCue, Track Photographer x5529 Mission Statement The Maryland Jockey Club is dedicated to presenting the great sport of Thoroughbred racing as the centerpiece of a high-quality entertainment experience providing fun and excitement in an inviting and friendly atmosphere for people of all ages . 1 THE MARYLAND JOCKEY CLUB Laurel Racing Assoc. Inc. • P.O. Box 130 •Laurel, Maryland 20725 301-725-0400 • www.laurelpark.com EXECUTIVE OFFICIALS STATE OF MARYLAND Sal Sinatra President and General Manager Lawrence J. Hogan, Jr., Governor Douglas J. Illig Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Tim Luzius Senior Vice President and Assistant General Manager Boyd K. -

Kentucky Derby, Flamingo Stakes, Florida Derby, Blue Grass Stakes, Preakness, Queen’S Plate 3RD Belmont Stakes

Northern Dancer 90th May 2, 1964 THE WINNER’S PEDIGREE AND CAREER HIGHLIGHTS Pharos Nearco Nogara Nearctic *Lady Angela Hyperion NORTHERN DANCER Sister Sarah Polynesian Bay Colt Native Dancer Geisha Natalma Almahmoud *Mahmoud Arbitrator YEAR AGE STS. 1ST 2ND 3RD EARNINGS 1963 2 9 7 2 0 $ 90,635 1964 3 9 7 0 2 $490,012 TOTALS 18 14 2 2 $580,647 At 2 Years WON Summer Stakes, Coronation Futurity, Carleton Stakes, Remsen Stakes 2ND Vandal Stakes, Cup and Saucer Stakes At 3 Years WON Kentucky Derby, Flamingo Stakes, Florida Derby, Blue Grass Stakes, Preakness, Queen’s Plate 3RD Belmont Stakes Horse Eq. Wt. PP 1/4 1/2 3/4 MILE STR. FIN. Jockey Owner Odds To $1 Northern Dancer b 126 7 7 2-1/2 6 hd 6 2 1 hd 1 2 1 nk W. Hartack Windfields Farm 3.40 Hill Rise 126 11 6 1-1/2 7 2-1/2 8 hd 4 hd 2 1-1/2 2 3-1/4 W. Shoemaker El Peco Ranch 1.40 The Scoundrel b 126 6 3 1/2 4 hd 3 1 2 1 3 2 3 no M. Ycaza R. C. Ellsworth 6.00 Roman Brother 126 12 9 2 9 1/2 9 2 6 2 4 1/2 4 nk W. Chambers Harbor View Farm 30.60 Quadrangle b 126 2 5 1 5 1-1/2 4 hd 5 1-1/2 5 1 5 3 R. Ussery Rokeby Stables 5.30 Mr. Brick 126 1 2 3 1 1/2 1 1/2 3 1 6 3 6 3/4 I. -

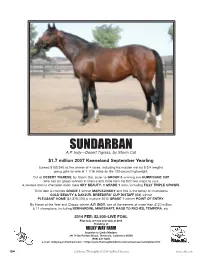

SUNDARBAN :Layout 1 12/4/13 1:15 PM Page 1

SUNDARBAN :Layout 1 12/4/13 1:15 PM Page 1 SUNDARBAN A.P. Indy—Desert Tigress, by Storm Cat $1.7 million 2007 Keeneland September Yearling Earned $103,340 as the winner of 4 races, including his maiden win by 8 3/4 lengths going gate-to-wire at 1 1/16 miles as the 123-pound highweight. Out of DESERT TIGRESS, by Storm Cat, sister to GROUP 3-winning sire HURRICANE CAT who has six group winners in France and Chile from his first two crops to race & second dam is champion older mare SKY BEAUTY,9GRADE 1 wins, including FILLY TRIPLE CROWN. Third dam is multiple GRADE 1 winner MAPLEJINSKY and this is the family of champions GOLD BEAUTY & DAYJUR, BREEDERS’ CUP DISTAFF (G1) winner PLEASANT HOME ($1,378,070) & multiple 2012 GRADE 1 winner POINT OF ENTRY. By Horse of the Year and Classic winner A.P. INDY, sire of the earners of more than $120 million & 11 champions, including BERNARDINI, MINESHAFT, RAGS TO RICHES, TEMPERA, etc. 2014 FEE: $2,500-LIVE FOAL First foals are two-year-olds of 2014 Standing at MILKY WAY FARM Inquiries to Linda Madsen 34174 De Portola Road, Temecula, California 92592 (909) 241-6600 e-mail: [email protected] • http://www.thoroughbredinfo.com/showcase/sundarban.htm 154 California Thoroughbred 2014 Stallion Directory www.ctba.com SUNDARBAN CS403401ORIGJockeyClubPageSent11-8-2013-1stChngLoretta11-27-2013-1052am:Layout 1 11/27/13 10:53 AM Page1 SUNDARBAN 2006 Bay - Height 16.2 - Dosage Profile: 8-12-21-1-0; DI: 2.65; CD: +0.64 Bold Ruler RACE AND (STAKES) RECORD Boldnesian Alanesian Age Starts 1st 2nd 3rd Earnings Bold Reasoning Hail to Reason 2 unraced 61 foals, 10 SWs Reason to Earn Sailing Home Seattle Slew 3 1 0 0 0 $170 Round Table 1050 foals, 114 SWs 4 9430 98,635 Poker Glamour My Charmer 5 6002 4,535 Jet Action 12 foals, 4 SWs 16 4 3 2 $103,340 Fair Charmer Myrtle Charm A.P. -

Violence Dark Bay Or Brown Horse Foaled March 21, 2010 Medaglia D

Sadler's Wells El Prado (IRE) Lady Capulet Medaglia d'Oro Bailjumper Violence Cappucino Bay Dubbed In Dark Bay or Brown Horse Mr. Prospector Foaled March 21, 2010 Gone West Violent Beauty Secrettame (2003) Storm Cat Storming Beauty Sky Beauty By MEDAGLIA D'ORO (1999), Black type winner, $5,754,720. Sire of 14 crops. 1606 foals, 1124 starters, 153 black type winners, 706 winners, $116,409,776, including Songbird (Champion twice, $4,692,000), Rachel Alexandra (Horse of the Year, Champion, $3,506,730), Wonder Gadot (Horse of the Year, Champion twice, $1,524,861), Souper Escape (Champion, $367,883), Passion for Gold (Champion, $269,910), Medaglia d'Orizaba (Champion), Talismanic (GB) ($2,744,435, Longines Breeders' Cup Turf [G1], etc.), Elate ($2,628,775, Alabama S. [G1], etc.). 1ST DAM VIOLENT BEAUTY, by Gone West. Winner at 4, $50,999 in US. Dam of 5 foals to race, 4 winners-- VIOLENCE (c, by Medaglia d'Oro). Black type winner, see records. Cinnamon Spice (f, by Candy Ride (ARG)). 4 wins at 4 and 5, $144,820 in US. 2ND DAM STORMING BEAUTY, by Storm Cat. Winner at 3, $32,063 in NA. Sister to HURRICANE CAT. Dam of 4 foals to race, 2 winners, including-- Smart Woman (f, by Smarty Jones). 7 wins at 4 and 5, $170,240 in US. Dam of 3 winners, including-- Bruntino. 5 wins, 2 to 4, $90,120 in US. 3RD DAM SKY BEAUTY, by Blushing Groom (FR). At 4 Champion Older Mare. 15 wins, 2 to 5, $1,336,000 in NA. -

Ruffian (1972 Reviewer

Ruffian by Kathleen Jones Ruffian was bred and owned by Mr & Mrs Stuart Janney for their Locust Hill Farm. She was born at Claiborne Farm in Kentucky from some breeding stock which the Janneys kept there. Her sire, Reviewer, won 9 of his 13 starts in a career plagued with injuries. Ruffian was a product of his first crop. Her dam, Shenanigans had won 3 of her 22 starts, and prior to foaling Ruffian, had already produced the good stakes winner Icecapade. Under the care of trainer Frank Whiteley Jr, her very first start came on May 22 at Belmont. The event was a 5 1/2 furlong maiden purse and Ruffian equaled the track record by running the distance in 1:03 flat. She was immediately moved up to stakes company and won the 5 1/2 furlong Fashion Stakes at Belmont in an identical time. The Janneys knew they had something special. Ruffian then won the Astoria Stakes at Aqueduct (5 1/2 furlongs) in 1:02 4/5. She appeared to be getting faster with every start. Her first attempt at 6 furlongs was in the Sorority Stakes at Monmouth in late July, and she won that clocking a very fast time of 1:09. This was followed up with a win in the Spinaway Stakes at Saratoga in which she ran the 6 furlongs in an even faster time of 1:08 3/5! As an undefeated multiple stakes winner of clearly superior skill and lightning fast speed, Ruffian was selected as the champion juvenile filly of 1974. -

JUMP START Dkb/Br, 1999

JUMP START dkb/br, 1999 height 16.2 Dosage (10-12-22-0-0); DI: 3.00; CD: 0.73 See gray pages—Bold Ruler RACE AND (BLACK TYPE) RECORD Bold Reasoning, 1968 Boldnesian, by Bold Ruler Age Starts 1st 2nd 3rd Earned 12s, BTW, $189,564 Seattle Slew, 1974 61 f, 10 BTW, 3.81 AEI Reason to Earn, by Hail to Reason 2 5 2(1) 1(1) 0 $221,265 17s, BTW, $1,208,726 Won Saratoga Special S (G2, $150,000, 6.5f in 1,050 f, 111 BTW, 3.69 AEI My Charmer, 1969 Poker, by Round Table 1:17.35), 2nd Champagne S (G1, 8.5f). A.P. Indy, dkb/br, 1989 32s, BTW, $34,133 11s, BTW, $2,979,815 12 f, 8 r, 6 w, 4 BTW Fair Charmer, by Jet Action SIRE LINE 1,184 f, 156 BTW, 2.89 AEI Secretariat, 1970 Bold Ruler, by Nasrullah JUMP START is by A.P. INDY, black-type stakes 8.24 AWD 21s, BTW, $1,316,808 winner of 8 races, $2,979,815, Horse of the Year and Weekend Surprise, 1980 653 f, 54 BTW, 2.98 AEI Somethingroyal, by Princequillo 31s, BTW, $402,892 champion 3yo colt, Belmont S (G1), Breeders’ Cup 14 f, 12 r, 9 w, 4 BTW Lassie Dear, 1974 Buckpasser, by Tom Fool Classic (G1), etc., and sire of more than 155 black- 26s, BTW, $80,549 type stakes winners, including MINESHAFT (Horse of 13 f, 12 r, 12 w, 4 BTW Gay Missile, by Sir Gaylord the Year and champion older male, G1), FESTIVAL OF Storm Bird, 1978 Northern Dancer, by Nearctic LIGHT (Horse of the Year in UAE, G3 in UAE), 6s, BTW, $169,181 BERNARDINI (champion 3yo colt, G1), HONOR CODE Storm Cat, 1983 682 f, 63 BTW, 2.26 AEI South Ocean, by New Providence 8s, BTW, $570,610 (champion older male, G1), RAGS TO RICHES (cham- 1,414 f, 177 BTW, 2.95 AEI Terlingua, 1976 Secretariat, by Bold Ruler pion 3yo filly, G1), MARCHFIELD (champion older Steady Cat, b, 1993 17s, BTW, $423,896 male twice in Can, G2A), etc. -

Bay Horse; Foaled 2010 by MALIBU MOON (1997). Winner of $33,840. Among the Leading Sires, Sire of 90 Black-Type Winners, Includi

ORB Bay Horse; foaled 2010 Seattle Slew A.P. Indy ............................ Weekend Surprise Malibu Moon .................... Mr. Prospector Macoumba ........................ Maximova (FR) ORB Fappiano Unbridled .......................... Gana Facil Lady Liberty ...................... (1999) Cox's Ridge Mesabi Maiden ................ Steel Maiden By MALIBU MOON (1997). Winner of $33,840. Among the leading sires, sire of 90 black-type winners, including champion Declan's Moon ($705,647, Hollywood Futurity [G1] (HOL, $267,900), etc.), and of Orb ($2,612,516, Kentucky Derby [G1] (CD, $1,414,800), Life At Ten [G1] ($1,277,515), Devil May Care [G1] ($724,000), Ask the Moon [G1] (10 wins, $713,640). 1st dam LADY LIBERTY, by Unbridled. 4 wins, 3 to 5, $202,045. Dam of 6 foals, 3 to race, 2 winners, including-- ORB (c. by Malibu Moon). Subject stallion. 2nd dam MESABI MAIDEN , by Cox's Ridge. 3 wins at 2 and 3, $240,314, Black-Eyed Susan S. [G2] , 3rd Monmouth Breeders' Cup Oaks [G2] , New York City Astarita S. [G2] , Anne Arundel S. [G3] . Dam of-- Steely Dame. 4 wins, 2 to 4, $45,006. 3rd dam STEEL MAIDEN , by Damascus. 4 wins to 3, $119,030, Dancealot S. [L] (LRL, $36,660), Resolution S. (LRL, $28,210), etc. Dam of 4 winners, incl.-- MESABI MAIDEN . Black-type winner, above. Pro Prospect . 8 wins, 3 to 6, $136,328, 2nd Sportsman's Park Budweiser Breeders' Cup H. [L] (SPT, $21,020), 3rd Better Bee S. (AP, $3,481). Sire. Women's Rights. Unraced. Producer. Granddam of SUGGESTIVE BOY (ARG) (Total: $730,654, champion twice in Argentina, Jockey Club [G1] , etc.), SUBTLETY (to 5, 2015, Total: $103,091, Republica Oriental Del Uruguay [G3] , etc.), Suffisant (Total: $32,467, 2nd Gran Premio Cri - adores Salvador Hess Riveros [G2] , Jose Saavedra Baeza [G3] , etc.). -

750 Orb 2010 Page 1

#750 Orb 2010 Page 1 Seattle Slew A.P. Indy Weekend Surprise Malibu Moon Mr. Prospector Orb Macoumba Maximova (FR) Bay Colt Fappiano Foaled February 24, 2010 Unbridled Lady Liberty Gana Facil (1999) Cox's Ridge Mesabi Maiden Steel Maiden By MALIBU MOON (1997), Winner, $33,840. Sire of 11 crops. 922 foals, 701 starters, 63 black type winners, 516 winners, $55,998,919, including Declan's Moon (Champion, $705,647), Life at Ten ($1,277,515, Beldame S. [G1], etc.), Orb ($921,050, Besilu Stables Florida Derby [G1], etc.), Devil May Care ($724,000, Frizette S. [G1], etc.), Malibu Mint ($723,829, Princess Rooney Handicap [G1], etc.), Ask the Moon ($713,640, Personal Ensign Invitational S. [G1], etc.), Malibu Prayer ($618,026, Ruffian Invitational H. [G1], etc.). 1ST DAM LADY LIBERTY, by Unbridled. 4 wins, 3 to 5, $202,045 in NA. Dam of 3 foals to race, 2 winners-- ORB (c, by Malibu Moon). Black type winner, see records. Cause of Freedom (g, by Alphabet Soup). 3 wins at 4 and 5, $105,834 in US. 2ND DAM MESABI MAIDEN, by Cox's Ridge. 3 wins at 2 and 3, $240,314 in NA. Won Black-Eyed Susan S. [G2]. 3rd Monmouth Breeders' Cup Oaks [G2], Astarita S. [G2], Anne Arundel S. [G3]. Dam of 6 foals to race, 2 winners, including-- Steely Dame (f, by Purge). 4 wins, 2 to 4, $45,006 in US. Altar Girl (f, by Pulpit). Placed at 2, $1,350 in NA. Placed at 3, $2,305 in US. (Total: $3,655) Dam of 2 winners, including-- Narita. -

Condition Book 1

2021 SPRING/SUMMER MEET CONDITION BOOK 1 APRIL 22 TO MAY 9 Joseph Appelbaum Stuart S. Janney, III Andrew Rosen Jeffrey A. Cannizzo Earle Mack George Russo Michael Dubb Timothy Mara Joseph Spinelli C. Steven Dunker Georgeanna Nugent Stuart Subotnick Marc Holiday David O’Rourke Vincent Tese Ogden Phipps II OFFICERS & SENIOR EXECUTIVES David O’Rourke, CEO & President Joseph Lambert, Executive Vice President, Chief Administrative Officer, General Counsel & Chief Compliance Officer Glen Kozak, Senior Vice President, Operations & Capitol Projects Tony Allevato, Chief Revenue Officer, President NYRA Bets Martin Panza, Senior Vice President, Racing Operations Renee Postel, Vice President, Chief Accounting Officer NEW YORK STATE GAMING COMMISION Barry C. Sample, Chair John A. Crotty, Commissioner Peter J. Moschetti, Jr., Commissioner John Poklemba, Esq., Commissioner Jerry Skurnik, Commissioner Todd R. Snyder, Commissioner Robert Williams, Acting Executive Director Ronald G. Ochrym, Director of Racing Edmund C. Burns, General Counsel Dr. Scott E. Palmer, Equine Medical Director New York State Gaming Commission PO Box 7500, Schenectady , NY 12301-7500 Send Questions or Comments to: [email protected];http://www.gaming.ny.gov/ NYRA is a member of the Thoroughbred Racing Associations And complies with its Code of Standards and By-Laws. Overnight Mailing Address: Belmont Race Course 2150 Hempstead Tnpk. Elmont, NY 11003 Telephone: (516) 488-6000 or (718) 641-4700 Outside New York (800) 221-6266 Inside New York (800) 221-6267 Private Lines (718) 659-2235 or (718) 659-2231 Racing Office Fax: (718) 659-3581 NYRA.com BELMONT RACETRACK 2021 Belmont Park Spring/Summer Meeting April 22nd-July 11th 48 Days Racing Department Stewards Braulio Baeza, Jr.