Legal Response to Propaganda Broadcasts Related to Crisis in and Around Ukraine, 2014–2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organisational Structure, Programme Production and Audience

OBSERVATOIRE EUROPÉEN DE L'AUDIOVISUEL EUROPEAN AUDIOVISUAL OBSERVATORY EUROPÄISCHE AUDIOVISUELLE INFORMATIONSSTELLE http://www.obs.coe.int TELEVISION IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION: ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURE, PROGRAMME PRODUCTION AND AUDIENCE March 2006 This report was prepared by Internews Russia for the European Audiovisual Observatory based on sources current as of December 2005. Authors: Anna Kachkaeva Ilya Kiriya Grigory Libergal Edited by Manana Aslamazyan and Gillian McCormack Media Law Consultant: Andrei Richter The analyses expressed in this report are the authors’ own opinions and cannot in any way be considered as representing the point of view of the European Audiovisual Observatory, its members and the Council of Europe. CONTENT INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................................6 1. INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK........................................................................................................13 1.1. LEGISLATION ....................................................................................................................................13 1.1.1. Key Media Legislation and Its Problems .......................................................................... 13 1.1.2. Advertising ....................................................................................................................... 22 1.1.3. Copyright and Related Rights ......................................................................................... -

Conceptualising Historical Crimes

Should crimes committed in the course of Conceptualising history that are comparable to genocide, crimes against humanity or war crimes be Historical Crimes referred to as such, whatever the label used at the time?180 This is the question I want to examine below. Let us compare the prob- lems of labelling historical crimes with his- torical and recent concepts, respectively.181 Historical concepts for historical crimes “Historical concepts” are terms used to de- scribe practices by the contemporaries of these practices. Scholars can defend the use of historical concepts with the argu- ment that many practices deemed inadmis- sible today (such as slavery, human sacri- fice, heritage destruction, racism, censor- ship, etc.) were accepted as rather normal and sometimes even as morally and legally right in some periods of the past. Arguably, then, it would be unfaithful to the sources, misleading and even anachronistic to use Antoon De Baets the present, accusatory labels to describe University of Groningen them. This would mean, for example, that one should not call the crimes committed during the Crusades crimes against hu- manity (even if a present observer would have good reason to qualify some of these crimes as such), for such a concept was nonexistent at the time. A radical variant of the latter is the view that not only recent la- bels should be avoided but even any moral judgments of past crimes. This argument, however, can be coun- tered with several objections. First, diverg- ing judgments. It is well known that parties V HISTOREIN OLU M E 11 (2011) involved in violent conflicts label these conflicts differently. -

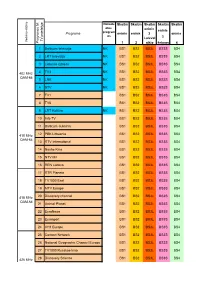

DISCOVER NEW WORLDS with SUNRISE TV TV Channel List for Printing

DISCOVER NEW WORLDS WITH SUNRISE TV TV channel list for printing Need assistance? Hotline Mon.- Fri., 10:00 a.m.–10:00 p.m. Sat. - Sun. 10:00 a.m.–10:00 p.m. 0800 707 707 Hotline from abroad (free with Sunrise Mobile) +41 58 777 01 01 Sunrise Shops Sunrise Shops Sunrise Communications AG Thurgauerstrasse 101B / PO box 8050 Zürich 03 | 2021 Last updated English Welcome to Sunrise TV This overview will help you find your favourite channels quickly and easily. The table of contents on page 4 of this PDF document shows you which pages of the document are relevant to you – depending on which of the Sunrise TV packages (TV start, TV comfort, and TV neo) and which additional premium packages you have subscribed to. You can click in the table of contents to go to the pages with the desired station lists – sorted by station name or alphabetically – or you can print off the pages that are relevant to you. 2 How to print off these instructions Key If you have opened this PDF document with Adobe Acrobat: Comeback TV lets you watch TV shows up to seven days after they were broadcast (30 hours with TV start). ComeBack TV also enables Go to Acrobat Reader’s symbol list and click on the menu you to restart, pause, fast forward, and rewind programmes. commands “File > Print”. If you have opened the PDF document through your HD is short for High Definition and denotes high-resolution TV and Internet browser (Chrome, Firefox, Edge, Safari...): video. Go to the symbol list or to the top of the window (varies by browser) and click on the print icon or the menu commands Get the new Sunrise TV app and have Sunrise TV by your side at all “File > Print” respectively. -

The Public Eye, Summer 2010

Right-Wing Co-Opts Civil Rights Movement History, p. 3 TheA PUBLICATION OF POLITICAL R PublicEyeESEARCH ASSOCIATES Summer 2010 • Volume XXV, No.2 Basta Dobbs! Last year, a coalition of Latino/a groups suc - cessfully fought to remove anti-immigrant pundit Lou Dobbs from CNN. Political Research Associates Executive DirectorTarso Luís Ramos spoke to Presente.org co-founder Roberto Lovato to find out how they did it. Tarso Luís Ramos: Tell me about your organization, Presente.org. Roberto Lovato: Presente.org, founded in MaY 2009, is the preeminent online Latino adVocacY organiZation. It’s kind of like a MoVeOn.org for Latinos: its goal is to build Latino poWer through online and offline organiZing. Presente started With a campaign to persuade GoVernor EdWard Rendell of PennsYlVania to take a stand against the Verdict in the case of Luis RamíreZ, an undocumented immigrant t t e Who Was killed in Shenandoah, PennsYl - k n u l Vania, and Whose assailants Were acquitted P k c a J bY an all-White jurY. We also ran a campaign / o t o to support the nomination of Sonia h P P SotomaYor to the Supreme Court—We A Students rally at a State Board of Education meeting, Austin, Texas, March 10, 2010 produced an “I Stand With SotomaYor” logo and poster that people could displaY at Work or in their neighborhoods and post on their Facebook pages—and a feW addi - From Schoolhouse to Statehouse tional, smaller campaigns, but reallY the Curriculum from a Christian Nationalist Worldview Basta Dobbs! continues on page 12 By Rachel Tabachnick TheTexas Curriculum IN THIS ISSUE Controversy objectiVe is present—a Christian land goV - 1 Editorial . -

Genocide and Belonging: Processes of Imagining Communities

GENOCIDE AND BELONGING: PROCESSES OF IMAGINING COMMUNITIES ADENO ADDIS* ABSTRACT Genocide is often referred to as “the crime of crimes.” It is a crime that is very high on the nastiness scale. The purpose of the genocidaire is of course to destroy a community—a community that he regards as a threat to his own community, whether the threat is perceived as physical, economic or cultural. The way this takes place and the complicity of law in this process has been extensively explored by scholars. But the process of destroying a community is perversely often simultaneously an “exercise in community build- ing,” a process through which intra-communal bonds and belong- ing are sought to be strengthened. This aspect of genocide has been entirely neglected by scholars, especially the role of law in that pro- cess. This article makes and defends two claims about communities and belonging in relation to genocide. First, it argues that as per- verse as it sounds, genocide is in fact an exercise in community building and law is highly implicated in that process. It defends the thesis with arguments that are conceptual as well as empirical. The second, and more hopeful, claim is that the international response * W. R. Irby Chair and W. Ray Forrester Professor of Public and Constitutional Law, Tulane University School of Law. Previous drafts of the paper were presented at an international conference at the Guanghua Law School of Zhejiang University (China) and at Tulane Law School faculty symposium. I thank participants at those meetings for the many helpful questions and comments. -

Skaitm Skaitm Skaitm Skaitm Skaitm Otos Eninis Eninis Programa Program Eninis Eninis 3 Eninis Os

Nekodu Skaitm Skaitm Skaitm Skaitm Skaitm otos eninis eninis Programa program eninis eninis 3 eninis os Laisval 3 TV priedėlyje TV Veikimo dažnis Programos Nr.Programos 1 2 aikio šeimos 4 1 Balticum televizija NK BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 2 LRT televizija NK BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 3 Lietuvos rytas.tv NK BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 402 MHz 4 TV3 NK BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 QAM-64 5 LNK NK BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 6 BTV NK BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 7 TV1 BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 8 TV6 BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 9 LRT Kultūra NK BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 10 Info TV BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 11 Balticum auksinis BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 410 MHz 12 PBK Lithuania BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 QAM-64 13 RTV International BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 14 Nashe Kino BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 15 NTV Mir BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 16 REN Lietuva BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 17 RTR Planeta BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 18 TV1000 East BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 19 MTV Europe BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 418 MHz 20 Discovery channel BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 QAM-64 21 Animal Planet BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 22 EuroNews BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 23 Eurosport BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 24 VH1 Europe BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 25 Cartoon Network BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 26 National Geographic Channel Europe BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 27 TV1000 Russkoe kino BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 426 MHz 28 Discovery Science BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 QAM-64 426 MHz QAM-64 29 Viasat Explorer BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 30 Viasat History BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 31 Viasat Motor BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 32 Viasat Sport Baltics BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 Detskij mir BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 33 Teleclub BS1 BS2 BS3L BS3S BS4 -

Combating Russian Disinformation in Ukraine: Case Studies in a Market for Loyalties

COMBATING RUSSIAN DISINFORMATION IN UKRAINE: CASE STUDIES IN A MARKET FOR LOYALTIES Monroe E. Price* & Adam P. Barry** I. INTRODUCTION This essay takes an oblique approach to the discussion of “fake news.” The approach is oblique geographically because it is not a discourse about fake news that emerges from the more frequently invoked cases centered on the United States and Western Europe, but instead relates primarily to Ukraine. It concerns the geopolitics of propaganda and associated practices of manipulation, heightened persuasion, deception, and the use of available techniques. This essay is also oblique in its approach because it deviates from the largely definitional approach – what is and what is not fake news – to the structural approach. Here, we take a leaf from the work of the (not-so) “new institutionalists,” particularly those who have studied what might be called the sociology of decision-making concerning regulations.1 This essay hypothesizes that studying modes of organizing social policy discourse ultimately can reveal or predict a great deal about the resulting policy outcomes, certainly supplementing a legal or similar analysis. Developing this form of analysis may be particularly important as societies seek to come to grips with the phenomena lumped together under the broad rubric of fake news. The process by which stakeholders assemble to determine a collective position will likely have major consequences for the * Monroe E. Price is an Adjunct Full Professor at the Annenberg School for Communication and the Joseph and Sadie Danciger Professor of Law at Cardozo School of Law. He directs the Stanhope Centre for Communications Policy Research in London, and is the Chair of the Center for Media and Communication Studies of the Central European University in Budapest.” ** Adam P. -

Critical Genocide Studies

Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Volume 7 Issue 1 Article 1 April 2012 Full Issue 7.1 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp Recommended Citation (2012) "Full Issue 7.1," Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal: Vol. 7: Iss. 1: Article 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol7/iss1/1 This Front Matter is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Editors’ Introduction Volume 7, issue 1 of Genocide Studies and Prevention continues the discussion of the state of the field of genocide studies that was initiated in volume 6, issue 3. Due to our (the editors’) keen desire to include as many different voices and perspectives as possi- ble, we reached out to old hands in the field, younger but well established scholars, and several scholars who recently completed their graduate studies but have already made an impact on the field. The sequence of the articles over the two issues began with comprehensive treat- ments and then moved into articles with more specific focuses, grouped thematically where applicable. Through the entire sequence across these two issues of GSP, we hope that readers will gain a solid sense of the history of the field and insight into some of the perdurable issues that have been at the heart of the field since its inception and that they have opportunities to reflect on the host of issues and concerns raised by authors coming from different disciplines (e.g., history, political science, sociology, psychology, philosophy) with vastly different perspectives. -

Elisa Elamus Kanalipaketid Kanalid Seisuga 27.02.2019

Elisa Elamus kanalipaketid kanalid seisuga 27.02.2019 XLR-pakett LR-pakett MR-pakett SR-pakett KANALI KANALI KANALI NIMI AUDIO SUBTIITRID KANALI NIMI AUDIO SUBTIITRID NR NR ETV HD 1 EST NTV Mir 63 RUS TV3 3 EST TV3+ 66 RUS ETV2 HD 4 EST Orsent TV 69 RUS TV6 5 EST TVN 70 RUS Tallinna TV HD 14 EST STS 71 RUS Cartoon Network 17 ENG; RUS Mir TV 80 RUS KidZone TV 20 EST; RUS Dom kino 87 RUS Euronews HD 21 ENG TNT4 90 RUS CNN 22 ENG TNT 93 RUS CNBC Europe 32 ENG Russki Illusion 99 RUS Deutsche Welle 56 ENG Pjatnitsa 117 RUS ETV+ HD 59 RUS TBN 300 EST PBK 60 RUS Meeleolukanal HD 300 EST RTR-Planeta 61 RUS Euronews 704 RUS REN TV Estonia 62 RUS Fox Life 8 ENG; RUS EST Alo TV 46 EST Fox 9 ENG; RUS EST MyHits HD 47 EST Sony Channel HD 10 ENG; RUS EST VH 1 48 ENG Eurosport 1 28 ENG; RUS TV7 57 EST Viasat History HD 33 ENG; RUS EST; FIN; LAT RTVi 65 RUS Discovery Channel 37 ENG; RUS EST TV XXI 67 RUS Animal Planet 38 ENG; RUS RTVi Nashe Kino 68 RUS Travel Channel 39 ENG; RUS EST; FIN Detski Mir 78 RUS Food Network 40 ENG; RUS EST Nostalgia 83 RUS Fine Living 43 ENG; RUS Sony Turbo HD 11 ENG; RUS Oruzie 97 RUS FilmZone HD 12 ENG; RUS AVTO 24 98 RUS FilmZone+ HD 13 ENG; RUS Mir 24 101 RUS TLC 15 ENG; RUS 1+1 International 103 UKR AMC 16 ENG; RUS Kto jest kto 106 RUS Nickelodeon 18 ENG; EST; RUS Shanson TV 108 RUS Pingviniukas 19 EST; RUS ZHARA 109 RUS Eurosport 2 29 ENG; RUS Kuhnja TV 110 RUS Setanta Sports 31 ENG; RUS Kinoseria 111 RUS Viasat Explore 34 ENG; RUS EST; FIN; LAT Voprosõ i Otvetõ 114 RUS National Geographic 36 ENG; RUS EST Psihologia 21 115 RUS ID Xtra 41 ENG; RUS EST Zdorovoe TV 119 RUS CBS Reality 42 ENG; RUS Domashnie zivotnõe 120 RUS Mezzo 45 FRA Zagorodnaja zhizn 121 RUS MTV Europe 51 ENG Usadba 122 RUS Eurochannel HD 52 ENG Illusion+ 123 RUS Life TV 58 RUS Inter+ 125 RUS TVCi 64 RUS Kinomedia 126 RUS Kanal Ju 73 RUS JCTV 127 ENG 24 Kanal 74 UKR TBN-Baltia HD 128 RUS Belarus 24 HD 75 RUS Tiji 131 RUS Nick Jr. -

10 Stages to Genocide

10 STAGES TO GENOCIDE This revised list replaces the previous 8 stages of Genocide based on Gregory H Stanton of Genocide Watch - Source: Genocide Watch http://genocidewatch.net/ 1. The differences between people are not respected. There is a division of ‘us’ CLASSIFICATION and ‘them’ - German and Jew, Hutu and Tutsi. 2. To the classification, names or symbols are used to distinguish between SYMBOLISATION people such as forcing Jewish people to wear the yellow star (and other symbols) under Nazi rule and the blue scarf for people to identify those the Khmer Rouge planned to murder. 3. The dominant group uses law, custom, and political power to deny the rights *NEW* of other groups. Examples include the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 in Nazi DISCRIMINATION Germany, which stripped Jews of their German citizenship, and prohibited their employment by the government and by universities. Denial of citizenship to the Rohingya Muslim minority in Burma is a current example. All human rights are stripped away. People are equated with animals, 4. vermin, insects or diseases. The Nazis referred to Jews as ‘vermin’ and during DEHUMANISATION the genocide in Rwanda, Tutsis were referred to as ‘cockroaches’. At this stage, hate propaganda in print and on radios are used to vilify the victim group. 5. Genocide is always organized, usually by the state, often using militias to ORGANISATION provide deniability of state responsibility. Special army units or militias are often trained and armed. 6. Propaganda continues to be spread by hate groups. The Nazis used the POLARISATION newspaper Der Stürmer to spread and incite messages of hate about Jewish people. -

The Holocaust and Mass Atrocity: the Continuing Challenge for Decision, 21 Mich

University of Florida Levin College of Law UF Law Scholarship Repository UF Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2013 The oloH caust and Mass Atrocity: The onC tinuing Challenge for Decision Winston P. Nagan University of Florida Levin College of Law, [email protected] Aitza M. Haddad Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Winston P. Nagan & Aitza M. Haddad, The Holocaust and Mass Atrocity: The Continuing Challenge for Decision, 21 Mich. St. Int'l L. Rev. 337 (2013), available at http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/612 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UF Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE HOLOCAUST AND MASS ATROCITY: THE CONTINUING CHALLENGE FOR DECISION * Winston P. Nagan & Aitza M. Haddad"~ Figure 1: Contemporary Art Expressions Symbolizing the Horror of the Holocaust' * Winston P. Nagan, J.S.D. (1977) is a Sam T. Dell Research Scholar Professor of Law at the University of Florida College of Law. He is widely published in human rights, a fellow of the RSA, and the interim Secretary General of WAAS. He is also an affiliate Professor of Anthropology and Latin American Studies and the Director of the University of Florida Institute for Human Rights, Peace and Development. ** Aitza M. Haddad, J.D. (2010), LL.M. -

Land Redistributions and the Russian Peasant Commune in the Late-Imperial Period

Land Redistributions and the Russian Peasant Commune in the Late-Imperial Period Steven Nafziger1 Preliminary and Incomplete Comments welcome and encouraged. Version: December, 2004 1Department of Economics, Yale University, [email protected]. This paper forms part of a larger project on the economics of rural development in Russia between 1861 and 1917. Research for this project was supported in part by the Title VIII Combined Research and Language Training Program, which is funded by the U.S. State Department and admin- istered by the American Councils for International Education: ACTR/ACCELS. The opinions expressed herein are the author’s and do not necessarily express the views of either the State Department or American Councils. Further support from the Economic History Association, the Sasakawa Foundation, Yale’s Economic Growth Center, and the Yale Center for Interna- tional and Area Studies is very much appreciated. The comments and suggestions of Tracy Dennison, Daniel Field, Timothy Guinnane, Mark Harrison, Valery Lazarev, Carol Leonard, Jason Long, Angela Micah, Carolyn Moehling, Benjamin Polak, Christopher Udry, and partic- ipants at the 2004 World Cliometric Congress, the 2004 Economic History Association meet- ings, and seminars at Yale and Harvard Universities were extremely helpful. Errors remain the exclusive property of the author. Abstract This paper investigates the motivations for, and effects of, intra-community land re- distributions by Russian peasants in the 19th century. Scholars such as Alexander Gerschenkron have emphasized that such repartitions of arable land create negative investment and innovation incentives and played a major role in hampering rural de- velopment in the period after serfdom.