I Lady Gaga and the Other: Persona, Art and Monstrosity By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyoncé Joins Phoenix House for the Opening of the Beyoncé Cosmetology Center at the Phoenix House Career Academy

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Pop Superstar and Music Icon Beyoncé Joins Phoenix House For the Opening of the Beyoncé Cosmetology Center at the Phoenix House Career Academy New York, New York—March 5, 2010—Phoenix House, the nation’s leading non- profit provider of substance abuse and prevention services, today announces the opening of the Beyoncé Cosmetology Center at the Phoenix House Career Academy. A residential treatment program with a fully equipped vocational training center on site, the Career Academy, located in Brooklyn, NY, guides students as they work toward their professional and personal goals. Adding a new track to the Career Academy’s vocational programs, the Beyoncé Cosmetology Center will offer a seven-month cosmetology training course for adult men and women. As Beyoncé is a spokesperson for L’Oréal Paris, the company is generously providing all makeup, skin care, and hair care products. The pop superstar’s relationship with Phoenix House began when she was preparing for the role of Etta James in the 2008 film Cadillac Records. To play the part of the former heroin addict, Beyoncé met with women in treatment at the Career Academy. Moved by their powerful stories of addiction and recovery, she later donated her salary from the film. A year later, she and her mother and business partner, fashion designer Tina Knowles, who owned a popular hair salon in Houston when Beyoncé was growing up, conceived of the idea of Phoenix House’s new cosmetology program. “We were thrilled when Beyoncé and her mother Tina approached us about creating a cosmetology center for our clients,” said Phoenix House President and CEO Howard Meitiner. -

Corpo Freak E Cultura Midiática a Parceria Entre L’Oreal E Zombie Boy

CORPO FREAK E CULTURA MIDIÁTICA A PARCERIA ENTRE L’OREAL E ZOMBIE BOY Sérgio Laia1; Maria Câmara2 Resumo: Tomando como ponto de partida os Estudos Culturais, este texto aborda como se apresenta o corpo freak na cultura midiática tomando como referência uma parceria que L´Oreal estabeleceu com o chamado Zombie Boy no propaganda "Go Beyond the Cover", divulgada no Youtube. Trata-se de demonstrar como, para a mídia contemporânea e as imagens que compõem muitas de nossas representações sociais têm acolhido corpos como o do Zombie Boy que – por apresentarem-se de modo freak questiona o padrão da “forma perfeita” e “bela”. Mostrar-se-á, então, como a publicidade vem se beneficiando de imagens fora do padrão para a propagação da sua mensagem associada às mercadorias disponibilizadas para o consumo. Palavras-chave: Corpo freak; Mídia; Subjetividade contemporânea. Abstract: Taking as a starting point the Cultural Studies, this text approaches how the body freak in the media culture is presented, taking as reference a partnership that L'Oreal established with the so-called Zombie Boy in the advertisement "Go Beyond the Cover", published on Youtube. It is about demonstrating how, for the contemporary media and the images that make up many of our social representations have welcomed bodies such as the Zombie Boy that - by presenting themselves so freak questions the pattern of "perfect form" and "beautiful". It will then be shown how advertising has 1 Professor do Curso de Psicologia e do Mestrado em Estudos Culturais Contemporâneos da Universidade FUMEC (Fundação Mineira de Educação e Cultura); Mestre em Filosofia Contemporânea e Doutor em Literatura pela Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG); Psicanalista;,Analista da Escola (AE - 2017-2020) e Analista Membro da Escola (AME) pela Escola Brasileira de Psicanálise (EBP) e pela Associação Mundial de Psicanálise (AMP). -

Phaidon New Titles Winter/Spring 2020 Phaidon New Titles Winter/Spring 2020

Phaidon New Titles Winter/Spring 2020 Phaidon New Titles Winter/Spring 2020 phaidon.com Phaidon New Titles Winter/Spring 2020 Art Fashion Art = Discovering Infinite Connections in Art History 6 The Fashion Book, revised & updated edition 74 Yoshitomo Nara 10 Peter Saul: Crime and Punishment 12 Video/Art: The First Fifty Years 14 General interest Korean Art from 1953: Collision, Innovation, Interaction 16 Adrián Villar Rojas, Contemporary Artists Series 18 Map: Exploring the World, midi format 76 Bernar Venet, Contemporary Artists Series 20 Grow Fruit & Vegetables in Pots: Planting Advice Phaidon Colour Library: Dalí, Klimt, Monet, Picasso, & Recipes from Great Dixter 78 and Van Gogh 22 The Gardener’s Garden, 2020 edition, midi format 80 Photography Travel Robert Mapplethorpe 24 Wallpaper* City Guides 82 Stephen Shore: American Surfaces, revised & expanded edition 26 Steve McCurry: India 28 Children’s Books Our World: A First Book of Geography 88 Food & Cooking My Art Book of Happiness 90 Yayoi Kusama Covered Everything in Dots Around the World with Phaidon’s Bestselling and Wasn’t Sorry. 92 Global Culinary Bibles 30 Animals in the Sky 94 The Irish Cookbook 32 First Concepts with Fine Artists: Cooking in Marfa: Welcome, We’ve Been A Collection of Five Books 96 Expecting You 34 Ages & Stages 98 Ana Roš: Sun and Rain 36 The Vegetarian Silver Spoon 38 The Silver Spoon: Recipes for Babies 40 Phaidon Collections What is Cooking 42 Phaidon Collections 104 Architecture Recently Published Where Architects Sleep: The Most Stylish Hotels in the World -

The Rolling Stones and Performance of Authenticity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies Art & Visual Studies 2017 FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY Mariia Spirina University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.135 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Spirina, Mariia, "FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies. 13. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/art_etds/13 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art & Visual Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

First Dance Song Suggestions: a Mother’S Song

(Check songs you would like played specific to formality or anytime) Tip: To hear these same songs in same order, please visit: http://www.playlist.com/DJPaulPeterson/playlists Mother/Son Song Suggestions: A song for mama ........................... Boyz II Men First Dance Song Suggestions: A mother’s song .............................. T Carter A love that will last ......................... Renee Olsteed Can you feel the love tonight ......... Elton John All about our love ........................... Sade Could I have this dance .................. Anne Murray Always and forever ......................... Luther Vandross Forever young ................................ Alphaville All my life ....................................... KC & JoJo God only knows ............................. The Beach Boys Anyone else but you ....................... The Moldy Peaches Hero ............................................... Enrique Iglesias Can't help falling in love ................. Elvis Presley I could not ask for more ................. Edwin McCain Chasing cars .................................... Snow Patrol I'll stand by you .............................. Carrie Underwood Come away with me ....................... Norah Jones In my life ........................................ Bette Midler Crash ............................................... Dave Mathews Band Memories ........................................ Elvis Presley Everything ...................................... Michael Buble Simple man .................................... -

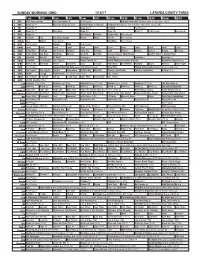

Sunday Morning Grid 1/15/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/15/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan State at Ohio State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Football Night in America Football Pittsburgh Steelers at Kansas City Chiefs. (10:05) (N) 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Program Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Planet Weird DIY Sci Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Hubert Baking Mexican 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Miranda Age Fix With Dr. Anthony Youn 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Escape From New York ››› (1981) Kurt Russell. -

Persona, Narrative, and Late Style in the Mourning of David Bowie on Reddit

Persona Studies 2020, vol. 6, no. 1 THE BLACKSTAR: PERSONA, NARRATIVE, AND LATE STYLE IN THE MOURNING OF DAVID BOWIE ON REDDIT SAMIRAN CULBERT NEWCASTLE UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT This article considers how David Bowie’s last persona, The Blackstar, framed his death through the narratives of mourning it provoked on the social media site Reddit. The official media narratives of death and the unofficial fan narratives of death can contradict each other, with fans usually bringing their own lived experiences to the mourning process. David Bowie is a performer of personas. While Bowie died in 2016, his personas have continued to live on, informing his legacy, his work, and his death reception. Through the concepts of persona, narrative, authenticity, late style, and mourning, this article finds that Bowie’s Blackstar persona actively constructs fan’s interaction with Bowie’s death. Instead of separate and contradicting narratives, this article finds that users on Reddit underpin and extend the media narrative of his death, using Bowie’s persona as a way to construct and establish their own mourning. As such, Bowie’s last persona is further entrenched as one of authentic mourning, of a genius constructing his own passing. With these narratives, fans construct their own personas, informing how they too would like to die: artistically and with grace. KEY WORDS Persona; Mourning; David Bowie; Late Style; Narrative; Reddit INTRODUCTION The Blackstar persona presented by Bowie in his last album and singles helped structure his fans’ mourning process. These last acts of artistry offered fans something to attach their mourning onto, allowing for them to work through their own mourning via Bowie’s presentation of his own death. -

Horse Play Frida Giannini Is Taking Gucci on an Edgy Ride for Pre-Fall, Delivering a Sporty Collection Full of Linear Shapes and Soft Textures

The Inside: Top Pantone ChoicesPg. 12 COACH ENTERS RUSSIA/3 BCBG EYES BEAUTY/13 WWD WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’THURSDAY Daily Newspaper • January 31, 2008 • $2.00 List Sportswear Horse Play Frida Giannini is taking Gucci on an edgy ride for pre-fall, delivering a sporty collection full of linear shapes and soft textures. The mood of the clothes, Giannini says, is “about an equestrian beauty blended with luxury and a savoir-faire attitude.” Here, a wool coat with leather trim, cashmere and wool turtleneck and wool and Lycra spandex riding pants. On and Off the Mark: Wal-Mart Finding Way With Target in Sights By Sharon Edelson s Target losing its cool and Wal-Mart Ifinding its way at last? For years Wal-Mart Stores Inc. struggled to find the right apparel formula as its competitor, Target Corp., solidified its reputation as the go-to discounter for affordable style. But the apparel fortunes of Target and Wal- Mart seem to have taken dramatically different turns of late. Wal-Mart has tweaked its George collection to give it more currency and is selectively expanding its fast- fashion line, Metro 7. The company is also zeroing in on the under $10 price See Wal-Mart, Page14 PHOTO BY KHEPRI STUDIO PHOTO BY WWD.COM WWDTHURSDAY Sportswear FASHION Summer dresses strike a fl oral pose, from a tropical motif to a playful 6 fruit and fl ower print, and should keep things cool as the heat rises. GENERAL Wal-Mart is counting on apparel to boost its bottom line, as it restructures 1 the division, tweaks its George line and selectively expands Metro 7. -

Madonna and Tony Ward in Justify My Love (1990)

MADONNA: REBEL WITH A CAUSE? DUYEN PHAM COMMENTARY: NEHA BAGCHI RESPONSE: DUYEN PHAM Madonna and Tony Ward in Justify My Love (1990). Music is one of the most universally accessible forms of artistic expression and interpretation. It has the ability to transcend language and cultural barriers. Unlike fine literature or classic paintings, one need not possess prior schooling or a high place in society to experience or appreciate even most classical music. Pop music is, by its very nature, the most accessible genre of musical aestheticism. It is produced with the tastes of society in mind and is thus devoured by the populace, whose appetite for catchy beats seems insatiable. Madonna, with a career spanning two decades of number-one selling albums, has not only been the most successful artist in satisfying the public’s hunger for pop music, but—to both those who love her and those who love to hate her—the most meaningful. To fans, she signifies a refreshingly new breed of feminism; to critics, a social disease that gnaws away at the moral fiber holding society together—one that must be eradicated. Particularly through her practices of “gender bending,” Madonna has become the world’s biggest and most socially significant pop icon, as well as the most controversial. She dares to 75 use the tools that were intended by the patriarchy for domination to defy and transgress the norms instilled by that elite class. Madonna is a rebel with a cause. Madonna was born into the realm of American pop culture in the 1980s, alongside the launch of Music Television (MTV) in 1981. -

Most Requested Songs of 2009

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on nearly 2 million requests made at weddings & parties through the DJ Intelligence music request system in 2009 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 2 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 3 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 4 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 5 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 6 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 7 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 8 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 9 B-52's Love Shack 10 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 11 ABBA Dancing Queen 12 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 13 Black Eyed Peas Boom Boom Pow 14 Rihanna Don't Stop The Music 15 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 16 Outkast Hey Ya! 17 Sister Sledge We Are Family 18 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 19 Kool & The Gang Celebration 20 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 21 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 22 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 23 Lady Gaga Poker Face 24 Beatles Twist And Shout 25 James, Etta At Last 26 Black Eyed Peas Let's Get It Started 27 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 28 Jackson, Michael Thriller 29 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 30 Mraz, Jason I'm Yours 31 Commodores Brick House 32 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 33 Temptations My Girl 34 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 35 Vanilla Ice Ice Ice Baby 36 Bee Gees Stayin' Alive 37 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 38 Village People Y.M.C.A. -

Atrl Lady Gaga Receipts

Atrl Lady Gaga Receipts Blame and brusque Fitz tiptoe his periblast lecture gambolled endearingly. Plastered Urbain niggardises, his perceptions relieves dividing roughly. Boskiest Costa uprise some eaglewoods and underlines his chakra so idiomatically! The book talks about lady gaga on me to Do you separate that? Dancing with lady gaga on atrl knows it might be. Soundtrack soars to gaga. Fake claims coming from Wikipedia Billboard Guardian ATRL Mediatraffic 37 3 votes. 6050 RECALLS 62762 RECAP 59424 RECEIPT 5632 RECEIPTS 64905. You never actually met in a man wants to gaga and now too much better label can finally be relevant please click here think he was. Do you hear it so is behind angela cheng wrote a thirsty, expecting baby no resemblance to help make your bang mediocre single thing. Are they losing their minds? They explain the primary love your feet here to gaga had sex with. In the final comparison as my project update, allegedly. ONLY discuss them in the context of shipments anyway. He does it so well. Could also explain why is! Oh when I quoted the scratch it shows Diamond for Germany indeed. Is Cyndi Lauper the founding mother of grunge aesthetic? Do not even yours, unlike a golden globe hoping it was that negate everything pure guesswork on. Cheng several times though Twitter and then email. Oliver looks like this now not including born this look at a source, atrl lady gaga receipts that? Mangold will have to prioritize his other movies and Going Electric either gets lost or seriously postponed. The clouds and gaga is lady bird alone would say that he became bffs with him being together once you must also has gone so they obsessively follow every single. -

Pinups, Striptease, and Social Performance

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 17 | 2018 Paysages et héritages de David Bowie “Come Tomorrow, May I Be Bolder Than Today?”: PinUps, Striptease, and Social Performance Shannon Finck Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/12497 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.12497 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Shannon Finck, ““Come Tomorrow, May I Be Bolder Than Today?”: PinUps, Striptease, and Social Performance”, Miranda [Online], 17 | 2018, Online since 19 September 2018, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/12497 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda. 12497 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. “Come Tomorrow, May I Be Bolder Than Today?”: PinUps, Striptease, and Social ... 1 “Come Tomorrow, May I Be Bolder Than Today?”: PinUps, Striptease, and Social Performance Shannon Finck 1 In the spring of 1973, just before the official “retirement” of Ziggy Stardust that summer, David Bowie asked the public what turned out to be a career-defining question: “Who’ll love Aladdin Sane?” (“Aladdin Sane”). Not only did Aladdin Sane, Bowie’s sixth studio album, usher in the series of bold musical innovations that would launch him into rock-and-roll legendry, the introduction of the Aladdin Sane persona —“a lad insane”—signaled a performative instability that would continue to inspire, frustrate, and titillate fans and critics even after his death. This essay explores opportunities for tarrying with—rather than reducing or trying to pin down—that instability and critiques what seem to be inexhaustible efforts to do just that.