Reappraising the Visionary Work of Arata Isozaki

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate

For publication on or after Monday, March 29, 2010 Media Kit announcing the 2010 PritzKer architecture Prize Laureate This media kit consists of two booklets: one with text providing details of the laureate announcement, and a second booklet of photographs that are linked to downloadable high resolution images that may be used for printing in connection with the announcement of the Pritzker Architecture Prize. The photos of the Laureates and their works provided do not rep- resent a complete catalogue of their work, but rather a small sampling. Contents Previous Laureates of the Pritzker Prize ....................................................2 Media Release Announcing the 2010 Laureate ......................................3-5 Citation from Pritzker Jury ........................................................................6 Members of the Pritzker Jury ....................................................................7 About the Works of SANAA ...............................................................8-10 Fact Summary .....................................................................................11-17 About the Pritzker Medal ........................................................................18 2010 Ceremony Venue ......................................................................19-21 History of the Pritzker Prize ...............................................................22-24 Media contact The Hyatt Foundation phone: 310-273-8696 or Media Information Office 310-278-7372 Attn: Keith H. Walker fax: 310-273-6134 8802 Ashcroft Avenue e-mail: [email protected] Los Angeles, CA 90048-2402 http:/www.pritzkerprize.com 1 P r e v i o u s L a u r e a t e s 1979 1995 Philip Johnson of the United States of America Tadao Ando of Japan presented at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. presented at the Grand Trianon and the Palace of Versailles, France 1996 1980 Luis Barragán of Mexico Rafael Moneo of Spain presented at the construction site of The Getty Center, presented at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. -

Open Source Architecture, Began in Much the Same Way As the Domus Article

About the Authors Carlo Ratti is an architect and engineer by training. He practices in Italy and teaches at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he directs the Senseable City Lab. His work has been exhibited at the Venice Biennale and MoMA in New York. Two of his projects were hailed by Time Magazine as ‘Best Invention of the Year’. He has been included in Blueprint Magazine’s ‘25 People who will Change the World of Design’ and Wired’s ‘Smart List 2012: 50 people who will change the world’. Matthew Claudel is a researcher at MIT’s Senseable City Lab. He studied architecture at Yale University, where he was awarded the 2013 Sudler Prize, Yale’s highest award for the arts. He has taught at MIT, is on the curatorial board of the Media Architecture Biennale, is an active protagonist of Hans Ulrich Obrist’s 89plus, and has presented widely as a critic, speaker, and artist in-residence. Adjunct Editors The authorship of this book was a collective endeavor. The text was developed by a team of contributing editors from the worlds of art, architecture, literature, and theory. Assaf Biderman Michele Bonino Ricky Burdett Pierre-Alain Croset Keller Easterling Giuliano da Empoli Joseph Grima N. John Habraken Alex Haw Hans Ulrich Obrist Alastair Parvin Ethel Baraona Pohl Tamar Shafrir Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include: The Elements of Modern Architecture The New Autonomous House World Architecture: The Masterworks Mediterranean Modern See our websites www.thamesandhudson.com www.thamesandhudsonusa.com Contents -

PDF Download Palladios Children : Essays on Everyday Environment

PALLADIOS CHILDREN : ESSAYS ON EVERYDAY ENVIRONMENT AND THE ARCHITECT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK N.J. Habraken | 224 pages | 30 Dec 2005 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9780415357913 | English | London, United Kingdom Palladios Children : Essays on Everyday Environment and the Architect PDF Book Her area of expertise is the development of civic spaces serving communities whose needs reside at the intersection of architecture, urbanism, and performance. He lectures in architecture and is a former American Institute of Architects bureaucrat. B25 He is the author of seven books, the subject of two recent ones and his recent publication of The Structure of the Ordinary MIT was widely reviewed internationally. He bellowed something about poodles sawing wood and women drawing - no woman, he said, could possibly be an architect. Nearly every important development in the modern architectural movement began with the proclamation of these convictions in the form of a program or manifesto. There is an entirely new chapter on the Danish architect Jorn Utzon, whose work, as exemplified in his design for the Sydney Opera House, Mr. She had the keenest eye, a gift like her brother's, for the design of space. They are able to measure the amount of order that is necessary for understanding and fascination to prevail even when chaotic actions take place and random objects appear on stage. Habraken studied architecture at Delft Technical University, the Netherlands from This must lead to a reassessment of architects' identities, values and education, and the contribution of the architect in the shaping of the built environment. O69 Radhika Khurana reading aloud to 20 odd year olds in the initial section, and some absorbed older students and teachers reading silently in a subsequent, better-daylit section. -

Me Tabolis Ts House S Under Cons Truction

Metabolists houses under construction ESSAYS PREVI: The Metabolists’ First, Last and Only Project BY EUI-SUNG YI With the special assistance by Bridget Ackeifi Cities in the sky, superhighways over the seas, floating layers of techno-villages. These utopic proposals for Japan were generated by a passionate and extraordinary group of young Japa- nese architects fueled by the futuristic vision to rebuild their nation. Parallel to their idealism, was the path of Peter Land, an Englishman by way of Yale and South America, tasked to plan housing for the poor. Incredibly, their idealism would cross and the Metabolists’ first and only project would be for a United Nations social housing development in a place very far from Japan: Peru. Eui-Sung Yi sat down with the group’s last living member, Fumihiko Maki, and the organizer of the project, Peter Land, to discuss this project and its place in modern urban design (read the interviews in pg. 65 and 68, respectively). Nearly 50 years ago, architect Peter Land initiated an The competition was an immense undertaking. In the end, architectural competition for the Peruvian capital of Lima. there were 86 different designs, 467 built homes housing 50 - 2014/1 The humble British architect did not devise a competition over 2.800 occupants, a school and a nursery, all within meant for the design of an avant-garde form for a museum 12,3 hectares of property, located only 7 km west of Lima’s or civic monument. Instead, Land, with the support of center. Land asked a total of 26 architectural firms to submit 1 2 his friend and President Fernando Belaúnde Terry and designs: 13 international teams and 13 Peruvian groups both docomomo prestigious members of the Peruvian academia, asked the composed of emerging and progressive architects. -

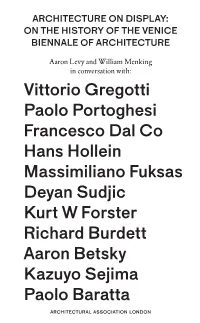

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

The Ethos in the Form Making of Grand Projects in Contemporary Beijing City .Fiotch

The Ethos in the Form Making of Grand Projects in Contemporary Beijing City By Keru Feng Bachelor of Architecture Beijing Polytechnic University, 1999 Submitted to the Department of Architecture in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2004 @ 2004 Keru Feng All rights reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author Department ofArchitecture May 19, 2004 Certif ied by Norman B. and Muriel Leventhal Professor of Architecture and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Julian Beinart Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students MASSACHUJSETTS INS fVTE OF TECHNOLOGY 2004 JUL 0 9 LIBRARIES . FiOTCH THESIS COMMITTEE Thesis Advisor William Porter Norman B. and Muriel Leventhal Professor of Architecture and Planning Thesis Reader Stanford Anderson Professor of History and Architecture; Head, Department of Architecture Thesis Reader Yan Huang Deputy Director of the Beijing Municipal Planning Commission The Ethos in the Form Making of Grand Projects in Contemporary Beijing City By Keru Feng Submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 19, 2004 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies ABSTRACT Capital cities embody national identity and ethos, buildings in the capital cities have the power to awe and to inspire. While possibly no capital city in the world is being renewed so intensely as Beijing, which presents both enormous potential and threat. Intrinsic to this research is a concept that the design culture of a city is formed largely by the national character, aesthetic value and culture distinctive to that city; these are the soil of design culture which merit careful observation and description. -

Limenarte 2011.Indd

Palazzo Comunale E. Gagliardi - Vibo Valentia 11 Dicembre 2010 - 23 Gennaio 2011 II edizione PREMIO INTERNAZIONALE LIMEN ARTE 2010 Palazzo Comunale E. Gagliardi Vibo Valentia 11 Dicembre 2010 - 23 Gennaio 2011 ENTE PROMOTORE CAMERA DI COMMERCIO VIBO VALENTIA COMMISSARIO Michele Lico SEGRETARIO GENERALE Donatella Romeo DIRETTORE ARTISTICO Giorgio Di Genova COMMISSIONE PREMI Toti Carpentieri Claudio Cerritelli Fabio De Chirico Giorgio Di Genova Enzo Le Pera Michele Lico Daniele Marino Nicola Micieli COORDINAMENTO ORGANIZZATIVO Raffaella Gigliotti COMUNICAZIONE Rosanna De Lorenzo PROGETTO GRAFICO, IMPAGINAZIONE E STAMPA Romano Arti Grafi che Tropea (VV) CURA CATALOGO, SERVIZI ACCOGLIENZA VISITATORI E VISITE GUIDATE Aleph Arte Lamezia Terme (CZ) Nel sommario: Interno di Palazzo Gagliardi SOMMARIO Si ringrazia l’Amministrazione Comunale di Vibo Valentia Introduzione Commissario Finito di stampare nel mese 5 di Dicembre 2010 Camera di Commercio Vibo Valentia Nessuna parte di questo catalogo Michele Lico può essere riprodotta in qualsiasi forma o con qualsiasi mezzo elettronico, meccanico o altro, senza l’autorizzazione scritta dei Testi Critici proprietari dei diritti d’autore. 9 © CCIAA Vibo Valentia Opere © per i testi i rispettivi Autori 35 Tutti i diritti riservati 135 Biografie 2 Introduzione del Commissario Michele Lico untuale, alla sua seconda edizione, il Premio In- ternazionale Lìmen Arte, si conferma, in un cre- scendo di consensi e di adesioni, prestigioso evento culturale che coniuga, nella mission che Pistituzionalmente abbiamo inteso affi dargli, la promozione del territorio attraverso l’attrattività del messaggio estetico dell’arte e l’aspetto “didattico e pedagogico” di fornire per- corsi di lettura e di decodifi cazione di un linguaggio che spes- so può apparire incomprensibile o stravagante, come dai più viene considerato proprio quello dell’arte contemporanea. -

GRIGORY MASLENNIKOV " ARCHITECTURAL CONSTRUCTIONS" Architectural Constructions

GRIGORY MASLENNIKOV " ARCHITECTURAL CONSTRUCTIONS" Architectural constructions Architecture is the language of giants, the greatest system of visual elements that was ever created by the humankind. Just like artists, architects are not inclined to talk much, because they are aiming to create tangible objects. Each creative professional has their own tools for communicating their thoughts and feelings. For me, the most complicated yet essential element of architecture and art is simplicity. Simple forms require perfect proportions and measurements that result in visual harmony. To achieve that in my works I experi- ment with texture and colours. It’s not an easy task trying to translate words into construction elements. But being an admirer of archi- tecture myself, I’m setting out on a mission to reimag-ine creations by leading architects of the world in paintings. It’s a complicated yet fascinating challenge. Please join me on my quest powered by imagination and by the artistic tools that will bring it into reality. Painting 1 Ettore Sottsass 170 х 120 cm oil, canvas The painting by the “patriarch of Italian design” is a reflection of his inclina-tion towards simple geome- try, bright colours and playful style. His architec-ture is intimate and is meant for people, not institutions. At its core is the tradi-tionally Medi- terranean approach to life - seizing every moment and enjoying simplicity. Painting 2 Arata Isozaki 170 х 120 cm oil, canvas, metal This work describes Isozaki’s own character. One of the leaders of the 1960s’ avant-garde movement, he learnt from Kenzo Tange and managed to introduce romanticism and humour into large-scale urban construction. -

The Vision of a Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao

HARVARD DESIGN SCHOOL THE VISION OF A GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM IN BILBAO In a March 31, 1999 article, the Washington Post? posed the following question: "Can a single building bring a whole city back to life? More precisely, can a single modern building designed for an abandoned shipyard by a laid-back California architect breath new economic and cultural life into a decaying industri- al city in the Spanish rust belt?" Still, the issues addressed by the article illustrate only a small part of the multifaceted Guggenheim Museum of Bilbao. A thorough study of how this building was conceived and made reveals equally significant aspects such as getting the best from the design architect, the master handling of the project by an inexperienced owner, the pivotal role of the executive architect-project man- ager, the dependence on local expertise for construction, the transformation of the architectural profession by information technology, the budgeting and scheduling of an unprecedented project without sufficient information. By studying these issues, the greater question can be asked: "Can the success of the Guggenheim museum be repeated?" 1 Museum Puts Bilbao Back on Spain’s Economic and Cultural Maps T.R. Reid; The Washington Post; Mar 31, 1999; pg. A.16 Graduate student Stefanos Skylakakis prepared this case under the supervision of Professor Spiro N. Pollalis as the basis for class discussion rather to illustrate effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation, a design process or a design itself. Copyright © 2005 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. To order copies or request permission to repro- duce materials call (617) 495-4496. -

400 Buildings 230 Architects 6 Geographical Regions 80 Countries a U R P E Or Am S Ica Fr a Ce Ia

400 Buildings 100 single houses┆53 schools┆21 art galleries 66 museums┆7 swimming pools┆2 town halls 230 Architects 52 office buildings┆33 unibersities┆5 international 6 Geographical Regions airports21 libraries┆5 embassies┆30 hotels 5 railway staions 80 Countries 80Architects dings Buil 125 ia As O ce an ZAHA HADID ARCHITECTS//OMA//FUKSAS//ASYMPTOTE ARCHITECTURE//ANDRÉS ia 6 5 PEREA ARCHITECT//SNØHETTA//BERNARD TSCHUMI//COOP HIMMELB(L)AU//FOSTER + B u i ld in g PARTNERS//UNStudio//laN+//KISHO KUROKAWA ARCHITECT AND ASSOCIATES//STEVEN s s t c e 8 it 0 h A c r HOLL ARCHITECTS//JOHN PORTMAN & ASSOCIATES//3DELUXE//TADAO ANDO ARCHITECT r c A h 0 it e 8 c t s & ASSOCIATES//MVRDV//SAUCIER + PERROTTE ARCHITECTES//ACCONCI STUDIO// s g n i d l i DRIENDL*ARCHITECTS//OGRYDZIAK / PRILLINGER ARCHITECTS//URBAN ENVIRONMENTS u B 5 0 ARCHITECTS//ORTLOS SPACE ENGINEERING//MOSHE SAFDIE AND ASSOCIATES INC.// 2 LOMA //JENSEN & SKODVIN ARKITEKTKONTOR AS+ARNE HENRIKSEN ARKITEKTER AS + e p o C-V HØLMEBAKK ARKITEKT//HENN ARCHITEKTEN//GIENCKE & COMPANY//CHETWOODS r u E A ARCHITECTS//AAARCHITECTEN//ABALOS+SENTKIEWICZ ARQUITECTOS//VARIOUS f r i ARCHITECTS//DENTON CORKER MARSHALL//SAMYN AND PARTNERS//ANTOINE PREDOCK// c a FREE Fernando Romero...... 3 5 s B t c u e i t l i d h i n c r g s A 0 8 8 0 s A g r c n i h d i l t i e u c B t s 0 9 a c i r e m A h t r o N S o u t h A m e r i c s t a c e t i h c r A 0 8 1 s 1 g n 5 i d B l i u ISBN 978-978-12585-2-6 7 8 9 7 8 1 Editorial Department of Global Architecture Practice Editorial Department of Global Architecture -

C:\Users\Gutschow\Documents\CMU Teaching\Postwar Modern

Arch. 48-350 -- Postwar Modern Architecture, S’13 Prof. Gutschow, Class #5 DISCUSSION: WHAT IS POSTWAR MODERN? Discuss: Joedicke, J. “Introduction,” Architecture Since 1945 (1969) Goldhagen & Legault, “Introduction: Critical Themes of Postwar Modernism,” in Anxious Modernisms Goldhagen, “Coda: Reconceptualizing Modernism,” in Anxious Modernisms Ockman: “Introduction,” in Architecture Culture, 1943-1968 Differentiate: Prewar Modernism; Postwar Modernism; Postmodernism Critical Themes of Postwar Modernism: Anxiety, Popular Culutre, Consumer Culture, Everyday Life, Anti- Architecture, Democratic Freedom, Homo Ludens (play), Primitivism, Authenticity, Architecture’s History, Regionalism, Place, Skepticism & Infatuation with Technology. Postwar Modern Architects & Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureates 2010: SANAA, Kazuyo Sejima + Ryue Nishizawa of Japan. 2009: Peter Zumthor of Switzerland 2008: Jean Nouvel of France 2007: Richard Rogers of the United Kingdom 2006: Paulo Mendez da Rocha of Brazil 2005: Thom Mayne of the United States 2004: Zaha Hadid of the United Kingdom 2003: Jorn Utzon of Denmark 2002: Glenn Murcutt of Australia 2001: Herzog and de Meuron of Switzerland 2000: Rem Koolhaas of The Netherlands 1999: Norman Foster of the United Kingdom 1998: Renzo Piano of Italy 1997: Sverre Fehn of Norway 1996: Rafael Moneo of Spain presented 1995: Tadao Ando of Japan 1994: Christian de Portzamparc of France 1993: Fumihiko Maki of Japan 1992: Alvaro Siza of Portugal 1991: Robert Venturi of the United States 1990: Aldo Rossi of Italy 1989: Frank O. Gehry of the United States 1988: Gordon Bunshaft of the United States and Oscar Niemeyer of Brazil 1987: Kenzo Tange of Japan 1986: Gottfried Boehm of Germany 1985: Hans Hollein of Austria 1984: Richard Meier of the United States 1983: Ieoh Ming Pei of the United States 1982: Kevin Roche of the United States 1981: James Stirling of Great Britain 1980: Luis Barragan of Mexico 1979: Philip Johnson of the United States. -

Eisenman Architects’ Map

1 INTRODUCTION M Matteo Cainer Matteo Cainer is a practising After receiving his master’s degree from the University In 2013 he co-founded and co-directed with Odile of Architecture in Venice, Italy, Matteo worked and Decq the Confluence Institute for Innovation and Office Principal architect, curator and educator. collaborated with a number of celebrated international Creative Strategies in Architecture in Lyon, France Based in London, he is Principal of practices including Peter Eisenman in New York and was Chair and professor until July 2015. City, Coop Himmelb(l)au in Vienna, and Arata Isozaki Matteo Cainer Architecture, founder Associati in Milan. It was in London that he then In March of 2020 to respond to the pandemic he of the Confluence Institute for created/directed the Design Research Studio at launches MCA Online a free educational initiative to Fletcher Priest Architects, and in June 2010 opened provide help and support to home-bound students Innovation and Creative Strategies his own practice. with tutorials, crits and a series of Lectures. He then in Architecture in Lyon, France and launches as part of Alphabet for the Futrure “What Now? Curatorially in 2004 he was Assistant Director to and ‘Post C-19!’ an Open Call to all the Architectural Director of Architecture Whispers. Kurt W. Forster for the 9th International Architecture Graduates of 2020 to imagine and sketch how Exhibition of la Biennale di Venezia - METAMORPH, they see and want the future to CHANGE. Matteo and in 2006 was appointed curator of the London continues to be a regular guest critic and jury member Architecture Biennale - CHANGE, with the exhibition: in various universities worldwide.