An Inland Bronze Age: Excavations At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Bradford Institutional Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bradford Scholars The University of Bradford Institutional Repository http://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk This work is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our Policy Document available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this work please visit the publisher’s website. Where available access to the published online version may require a subscription. Author(s): Gibson, Alex M. Title: An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Publication year: 2012 Book title: Enclosing the Neolithic : Recent studies in Britain and Ireland. Report No: BAR International Series 2440. Publisher: Archaeopress. Link to publisher’s site: http://www.archaeopress.com/archaeopressshop/public/defaultAll.asp?QuickSear ch=2440 Citation: Gibson, A. (2012). An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? In: Gibson, A. (ed.). Enclosing the Neolithic: Recent studies in Britain and Europe. Oxford: Archaeopress. BAR International Series 2440, pp. 1-20. Copyright statement: © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2012. An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Alex Gibson Abstract This paper summarises 80 years of ‘henge’ studies. It considers the range of monuments originally considered henges and how more diverse sites became added to the original list. It examines the diversity of monuments considered to be henges, their origins, their associated monument types and their dates. Since the introduction of the term, archaeologists have often been uncomfortable with it. -

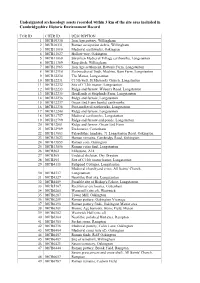

Undesignated Archaeology Assets Recorded Within 3 Km of the Site Area Included in Cambridgeshire Historic Environment Record

Undesignated archaeology assets recorded within 3 km of the site area included in Cambridgeshire Historic Environment Record TOR ID CHER ID DESCRIPTION 1 MCB10330 Iron Age pottery, Willingham 2 MCB10331 Roman occupation debris, Willingham 3 MCB11010 Medieval earthworks, Oakington 4 MCB11027 Hollow way, Oakington 5 MCB11069 Shrunken Medieval Village earthworks, Longstanton 6 MCB11369 Ring ditch, Willingham 7 MCB11965 Iron Age settlement, Hatton's Farm, Longstanton 8 MCB12110 Post-medieval finds, Machine Barn Farm, Longstanton 9 MCB12230 The Manor, Longstanton 10 MCB12231 C13th well, St Michael's Church, Longstanton 11 MCB12232 Site of C13th manor, Longstanton 12 MCB12233 Ridge and furrow, Wilson's Road, Longstanton 13 MCB12235 Headlands at Striplands Farm, Longstanton 14 MCB12236 Ridge and furrow, Longstanton 15 MCB12237 Green End Farm hamlet earthworks 16 MCB12238 Post-medieval earthworks, Longstanton 17 MCB12240 Ridge and furrow, Longstanton 18 MCB12757 Medieval earthworks, Longstanton 19 MCB12799 Ridge and furrow and ponds, Longstanton 20 MCB12801 Ridge and furrow, Green End Farm 21 MCB12989 Enclosures, Cottenham 22 MCB13003 Palaeolithic handaxe, 71 Longstanton Road, Oakington 23 MCB13623 Human remains, Cambridge Road, Oakington 24 MCB13853 Roman coin, Oakington 25 MCB13856 Roman coins find, Longstanton 26 MCB362 Milestone, A14 27 MCB365 Undated skeleton, Dry Drayton 28 MCB395 Site of C15th manor house, Longstanton 29 MCB4118 Fishpond Cottages, Longstanton Medieval churchyard cross, All Saints' Church, 30 MCB4317 Longstanton 31 MCB4327 -

History Timeline from 13.7 Billion Years Ago to August 2013. 1 of 588 Pages This PDF History Timeline Has Been Extracted

History Timeline from 13.7 Billion Years ago to August 2013. 1 of 588 pages This PDF History Timeline has been extracted from the History World web site's time line. The PDF is a very simplified version of the History World timeline. The PDF is stripped of all the links found on that timeline. If an entry attracts your interest and you want further detail, click on the link at the foot of each of the PDF pages and query the subject or the PDF entry on the web site, or simply do an internet search. When I saw the History World timeline I wanted a copy of it for myself and my family in a form that we could access off-line, on demand, on the device of our choice. This PDF is the result. What attracted me particularly about the History World timeline is that each event, which might be earth shattering in itself with a wealth of detail sufficient to write volumes on, and indeed many such events have had volumes written on them, is presented as a sort of pared down news head-line. Basic unadorned fact. Also, the History World timeline is multi-faceted. Most historic works focus on their own area of interest and ignore seemingly unrelated events, but this timeline offers glimpses of cross-sections of history for any given time, embracing art, politics, war, nations, religions, cultures and science, just to mention a few elements covered. The view is fascinating. Then there is always the question of what should be included and what excluded. -

Going for Gold – the South Cambridgeshire Story

Going for gold The South Cambridgeshire story Written by Kevin Wilkins March 2019 Going for gold Foreword Local government is the backbone of our party, and from Cornwall to Eastleigh, Eastbourne to South Lakeland, with directly elected Mayors in Bedford and Watford, Liberal Democrats are making a real difference in councils across the country. So I was delighted to be asked to write this foreword for one of the latest to join that group of Liberal Democrat Jo Swinson MP CBE councils, South Cambridgeshire. Deputy Leader Liberal Democrats Every council is different, and their story is individual to them. It’s important that we learn what works and what doesn’t, and always be willing to tell our story so others can learn. Good practice booklets like this one produced by South Cambridgeshire Liberal Democrats and the Liberal Democrat Group at the Local Government Association are tremendously useful. 2 This guide joins a long list of publications that they have produced promoting the successes of our local government base in places as varied as Liverpool, Watford and, more recently, Bedford. Encouraging more women to stand for public office is a campaign I hold close to my heart. It is wonderful to see a group of 30 Liberal Democrat councillors led by Councillor Bridget Smith, a worthy addition to a growing number of Liberal Democrat women group and council leaders such as Councillor Liz Green (Kingston Upon Thames), Councillor Sara Bedford (Three Rivers) Councillor Val Keitch (South Somerset), Councillor Ruth Dombey (Sutton), and Councillor Aileen Morton (Argyll and Bute) South Cambridgeshire Liberal Democrats are leading the way in embedding nature capital into all of their operations, policies and partnerships, focusing on meeting the housing needs of all their residents, and in dramatically raising the bar for local government involvement in regional economic development. -

Gabriel Moshenska ARCHAEOLOGICAL

Fennoscandia archaeologica XXXVII (2020) THEMED SECTION: COMMUNITIES AND THEIR ARCHAEOLOGIES IN FINLAND AND BRITAIN Gabriel Moshenska ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS AS SITES OF PUBLIC PROTEST IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY BRITAIN Abstract What happens when an archaeological excavation becomes the focus for media attention and public outrage? Protests of all kinds, ranging from letter-writing and legal challenges to mass rallies and illegal occupations, are a longstanding feature of global public archaeology. In this paper, I ex- amine this phenomenon through three case studies of protest in UK archaeology, dating from the 1950s to the 1990s: the Temple of Mithras in the City of London, the Rose Theatre in Southwark, and the ‘Seahenge’ timber circle in Norfolk. The accounts of these sites and the protest move- ments that they sparked reveal a set of consistent themes, including poor public understanding of rescue archaeology, an assumption that all sites can be ‘saved’, and the value of good stakeholder consultation. Ultimately, most protests of archaeological excavations are concerned with the pow- er of private property and the state over heritage: the core of the disputes – and the means to resolve them – are out of the hands of the archaeologists. Keywords: contested heritage, heritage management, public archaeology, social movements Gabriel Moshenska, UCL Institute of Archaeology, 31-34 Gordon Square, London, WC1H 0PY, UK: [email protected]. Received: 7 May 2020; Revised: 26 June 2020; Accepted: 26 June 2020. INTRODUCTION from police, construction workers, and senior archaeologists. After three weeks the occupation ‘Operation Sitric’ was launched in June 1979 ended peacefully. When archaeological work fi- when a group of 52 protestors, including aca- nally ended, large areas of the site remained un- demics and local politicians, broke into the ar- excavated and were destroyed by the developers. -

Hypro Building, Station Rd, Longstanton, Cambrideshire, Cb24 3Ds to Let

PRELIMINARY DETAILS 01223Warehouse 841 841 and office– 9,617 sq ft (893.45 sq m) In Brief ● Part of a larger building of industrial and office accommodation ● Good yard and parking area ● 3 miles from the A14 ● The new Northstowe development nearby HYPRO BUILDING, STATION RD, LONGSTANTON, CAMBRIDESHIRE, CB24 3DS TO LET 01223 841 841 bidwells.co.uk Location Longstanton is a village located 6 miles to the North West of Cambridge. The building is located 1.5 miles away from the new Northstowe Development which will provide over 10,000 new homes to the area. The A14 provides access to Huntingdon and the Midlands and East Coast Ports, as well as the M11 and M25 for Stansted Airport and London. Description The subject premises is of steel portal frame construction with brickwork and profile metal sheet cladding to elevations. The premises benefits from: ● Office and ancillary accommodation ● WC facilities ● Clear eaves height of approximately 3m (up to a maximum of 5.7m) ● 2 Roller shutter doors ● Good yard and parking provisions and Accommodation entrance to the rear sq ft sq m ● An onsite CCTV security system and Office 2,480 230.40 gatehouse Warehouse 7,137 663.05 Total 9,617 893.45 Additional Information Terms Value Added Tax The property is available on a FRI lease with Prices outgoings and rentals are quoted terms to be agreed. Quoting rent available on exclusive of but may be liable to VAT. application. EPC Rates Available upon request Business rates payable are currently calculated from the rateable value of the entire Postcode building. -

Architecture and Meaning in the Structure of Stonehenge, Wiltshire, UK Timothy Darvill

Houses of the Holy: architecture and meaning in the structure of Stonehenge, Wiltshire, UK Timothy Darvill Timothy Darvill is Professor of Archaeology in the Department of Archaeology, Anthropology and Forensic Science, Bournemouth University, UK. His research interests lie in the Neolithic of Northwest Europe and in archaeological resource management, and he has carried out fieldwork in Germany, Russia, Malta, England, Wales, and the Isle of Man. In 2008, together with Geoff Wainwright, he undertook excavations inside the stone circles at Stonehenge as part of ongoing research into the links between Stonehenge and the sources of the Bluestones in the Preseli Hills of southwest Wales. He is a member of the Editorial Advisory Board of Time & Mind. [email protected]. Abstract Stonehenge in central southern England is internationally known. Recent re-evaluations of its date and construction sequence provides an opportunity to review the meaning and purpose of key structural components. Here it is argued that the central stone structures did not have a single purpose but rather embody a series of symbolic representations. During the early third millennium this included a square-in- circle motif representing a sacred house or ‘big house’ edged by the five Sarsen Trilithons. During the late third millennium BC, as house styles changed, some of the stones were re-arranged to form a central oval setting that perpetuated the idea of the a sacred dwelling. The Sarsen Circle may have embodied a time- reckoning system based on the lunar month. From about 2500 BC more than 80 bluestones were brought to the site from sources in the Preseli Hills of west Wales about 220km distant. -

Meeting Papers Full Council Meeting, 11Th November 2019

- Longstanton Parish Council Meeting Papers Full Council Meeting, 11th November 2019 LongstantonPC 1 19-20/110 Northstowe Matters a) To receive a report following the Community Forum held on 6th November 2019 at the new Northstowe Secondary School. b) To receive an update on Northstowe matters from Jon London, Community Project Officer. 19-20/111 Finance Matters a) To receive an update on the financial position of the council from the Clerk. b) The Clerk noted that the Precept Request letter had been received from South Cambs District Council (appendix 1). It is asked whether the Parish Council wishes to comment on the consultation in Appendix A of the document and if so, a response is required by 18th November 2019. The Clerk noted that there is nothing significantly different to previous years when LPC have not made any comment. c) The Clerk noted that some tree work is required to Council trees following the survey carried out in March 2018 by Acacia Tree Surgery. The Clerk has approached Brookfield Groundcare (appendix 2) to get comparative costs to those provided by Acacia listed below: Acacia £4,130 Brookfield Groundcare £3,470 Recommendation: to employ Brookfield Groundcare to carry out the tree work as it is both more cost effective and they have itemised some additional work to be undertaken which has developed since the time of the survey in 2018. 19-20/112 Planning Matters (links to all planning applications can be found on the website: http://www.longstanton-pc.gov.uk/Planning_Applications_22977.aspx) a) Presentation to be made by Quinton Carroll from Cambridgeshire County Council about an application for a shared Heritage Facility between Northstowe, Longstanton and A14. -

Prehistory 2

Prehistory 2: The Bronze Age The Bronze Age (2500 BC—800 BC) During the Bronze Age the people living in Britain began to use copper and then bronze to make tools and weapons. Bronze was 90% copper and 10% n and much harder than copper on its own. Copper ore and n oxide was heated in a furnace to make molten bronze that could be poured into clay or sand moulds. Burials of important people take place in small round barrows with somemes later burials added. Many of these burials have highly decorave Beaker poery in them. It is believed that some of these Beaker people came to Britain from Europe bringing with them the knowledge of metallurgy. Decoraon could be applied to the poery by pressing a bone or wooden comb, using a piece of twisted cord or by the use of fingernails to create the impressions on the wet clay before firing on an open fire. The Amesbury Archer burial near to Stonehenge is the richest Bronze Age burial found in Britain. He arrived in Britain from around the Alps region in Europe and was buried with around 100 objects including, copper knives, gold hair tresses, pots and archer’s wrist guards. Tin was mined from Devon and Cornwall and copper ore from sites such as the Great Orme mine in Wales which extended to a depth of 70m. The Isleham Hoard is the largest collecon of bronze items ever found in Britain. It consists of around 6500 objects from swords, spearheads and axes to ornaments and sheet bronze. -

Longstanton Life Volume 20, Issue No

Longstanton Life Volume 20, Issue No. 2 April - May 2020 Life in Your Locality d d u R a n n A y b o t o h P . s l i d o ff a D The information in The Longstanton Life is provided in good faith and we have tried to ensure that it is accurate and correct. However, neither the editorial team nor the contributors can be held responsible for any inaccuracies or omissions or any consequential losses of any form whatsoever arising therefrom. The editorial team for this edition were: Anna Rudd, Tony Cowley, Manjeet Bolla, Beth Baker, Tracy Cole, Georgie Edwards and John Pratt . The Longstanton Life newsletter is Copyright © 2000 - 2020 The Editorial Team. All Rights Reserved. Editorial graphics © LLife V I L L AG E D I A RY DUE TO CORONAVIRUS PLEASE CHECK WITH THE ORGANISER FIRST SUNDAY 0930-1030 Sunday School Village Institute* Susan Meah 01954 781258 1100 Tennis Club Sessions The Pavilion Sarah Ballard 07985 938959 MONDAY 1100-1200 Zumba Gold Village Institute* Davina Mee 07779 244250 1800-2000 Bowls Club The Pavilion Marion Edwards 01954 780118 1930-2030 Jazzercise Hatton Park School Tina Chasse 01487 841811 2nd of month 1930 Parish Council Village Institute* (Open meeting) 3rd of month 1945 W.I. Village Institute* Patrizia Peters 01954 781283 TUESDAY 1000-1200 Coffee morning (over 55's) The Dale Comm. Hall Please just turn up 1030-1115 Mini JAFFAs (pre-schoolers) All Saints’ Church Susan Meah 01954 781258 1700-2000 Tennis - Junior and adult coaching The Pavilion [email protected] 1830-2000 Adult Cricket training (May-August) Recreation Ground Wayne Markillie 07737 313225 1900-1945 SRF Bootcamp Recreation Ground Shane Rackham 07912 555301 1900-2100 Cambridge Freestyle Martial Arts Village Institute* Rory / Martin 07523 854251 / 07535 646234 1900-2130 ATC (Air Training Corps) Cadet Centre WEDNESDAY 1000-1100 Music Madness (0-5yrs) Village Institute* Sharon Sennitt 07762 206320 1800 Tennis Club Night The Pavilion Sarah Ballard 07985 938959 1910-2130 Army Cadet Force (12-18yrs) Cadet Centre Sgt. -

Seahenge: a Quest for Life and Death in Bronze Age Britain Free

FREE SEAHENGE: A QUEST FOR LIFE AND DEATH IN BRONZE AGE BRITAIN PDF Francis Pryor | 368 pages | 07 May 2002 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007101924 | English | London, United Kingdom Seahenge: a quest for life and death in Bronze Age Britain - Francis Pryor - Google книги The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Packaging should be the same as what is found in a retail store, unless the item is handmade or was packaged by the manufacturer in non-retail packaging, such as an unprinted box or plastic bag. See details for additional description. Skip to main content. About this product. Make an offer:. Stock photo. Brand new: Lowest price The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Title: Seahenge. Catalogue Number: Format: BOOK. Missing Information?. See all 4 brand new listings. Buy It Now. Add to cart. About this product Product Information A lively and authoritative investigation into the lives of our ancestors, based on the revolution in the field of Bronze Age archaeology which has been taking place in Norfolk and the Fenlands over the last Seahenge: A Quest for Life and Death in Bronze Age Britain years, and in which the author has played a central role. One of the most haunting and enigmatic archaeological discoveries of recent times was the uncovering in at low tide of the so-called Seahenge off the north coast of Norfolk. This circle of wooden planks set vertically in the sand, with a large inverted tree-trunk in the middle, likened to a ghostly 'hand reaching up from the underworld', has now been dated back to around BC. -

Bar Hill Longstanton Willingham Over Swavesey 5 | 5A

Bar Hill Longstanton Willingham Over Swavesey 5 | 5A MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS (excluding Bank Holidays) 5A 5A 5A 5A 5A Over City Centre Emmanuel Street E4 - 0930 1130 1330 1510 Willingham Girton Corner - 0942 1142 1342 1522 Bar Hill Shopping Centre - 0954 1154 1354 1544 interchange point Trn Trn Trn Trn Bar Hill Shopping Centre - 1005 1205 1405 1605 Longstanton Church - 1012 1212 1412 1612 Longstanton Park & Ride - 1018 1218 1418 1618 Longstanton Swavesey Willingham Willford Furlong - 1025 1225 1425 1625 Park & Ride Over Green - 1035 1235 1435 1635 Swavesey Middle Watch 0841 1042 1242 1442 1642 Longstanton Park & Ride 0849 1051 1251 1451 1651 Longstanton Church 0852 1054 1254 1454 1654 Longstanton Bar Hill Shopping Centre 0859 1101 1301 1501 1701 interchange point Trn Trn Trn Trn Trn Bar Hill Shopping Centre 0915 1115 1315 1525 1705 Bar Hill Bar Hill Appletrees 0921 1121 1321 1533 1711 Girton Corner 0930 1130 1330 1543 1721 City Centre Emmanuel Street E4 0946 1146 1346 1604 1744 SATURDAYS (excluding Bank Holidays) 5A 5A 5A 5A 5A City Centre Emmanuel Street E4 - 0930 1120 1320 1520 Girton Corner - 0944 1134 1334 1534 Bar Hill Shopping Centre - 0954 1149 1349 1549 interchange point Trn Trn Trn Trn Bar Hill Shopping Centre - 1005 1205 1405 1605 Longstanton Church - 1012 1212 1412 1612 Longstanton Park & Ride - 1018 1218 1418 1618 Willingham Willford Furlong - 1025 1225 1425 1625 Over Green - 1035 1235 1435 1635 Swavesey Middle Watch 0826 1042 1242 1442 1642 Longstanton Park & Ride 0834 1051 1251 1451 1651 Longstanton Church 0837 1054 1254 1454 1654 Bar Hill Shopping Centre 0844 1101 1301 1501 1701 interchange point Trn Trn Trn Trn Trn Bar Hill Shopping Centre 0855 1115 1315 1515 1715 KEY Bar Hill Appletrees 0900 1120 1320 1520 1720 Transfer at Bar Hill for all journeys to and Girton Corner 0910 1130 1330 1530 1730 Trn from Cambridge.