Backing for a Big Idea - Consensus Building for Strategic Planning in Cambridge Stephen Platt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

19LAD0119 Land Fund Appendices

Matter 4: Appendix 1.1 Credentials of Charles Crawford, MA (Cantab), DipLA, CMLI Charles Crawford is a Board Director of LDA Design with extensive experience of Green Belt matters. Of most relevance is the work he undertook on behalf of Cambridge City and South Cambridgeshire District Councils in relation to the examination of their Local Plans. When the Cambridge City and South Cambridgeshire Local Plan examinations were suspended in 2015, Mr Crawford was appointed by the two Councils to undertake a review of the inner boundary of the Cambridge Green Belt. His subsequent report, the Cambridge Inner Green Belt Boundary Study (CIGBBS) became part of the Councils’ evidence base and Mr Crawford appeared on behalf of the Councils when the examination hearings resumed. The Inspectors’ reports were published in August 2018. An excerpt from the Cambridge City report is attached as Appendix 1.2, (the South Cambridgeshire report is very similar in relation to strategic matters such as Green Belt, save for issues and sites that solely affect one of the two Councils). Paragraph 53 of Appendix 1.2 states the Inspectors’ finding that the methodology employed in the CIGBBS is based on a reasoned judgement and is a reasonable approach to take. Paragraph 54 states that the Inspectors find the CIGBBS to be a robust approach which follows the PAS advice. The Inspectors supported the conclusions of the CIGBBS in relation to Green Belt releases, save in one minor respect. Appendix 1.3 contains an excerpt from the CIGBBS, covering the assessment of sector 10, one of the areas adjoining the south edge of Cambridge. -

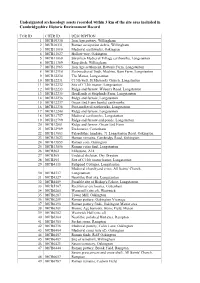

Undesignated Archaeology Assets Recorded Within 3 Km of the Site Area Included in Cambridgeshire Historic Environment Record

Undesignated archaeology assets recorded within 3 km of the site area included in Cambridgeshire Historic Environment Record TOR ID CHER ID DESCRIPTION 1 MCB10330 Iron Age pottery, Willingham 2 MCB10331 Roman occupation debris, Willingham 3 MCB11010 Medieval earthworks, Oakington 4 MCB11027 Hollow way, Oakington 5 MCB11069 Shrunken Medieval Village earthworks, Longstanton 6 MCB11369 Ring ditch, Willingham 7 MCB11965 Iron Age settlement, Hatton's Farm, Longstanton 8 MCB12110 Post-medieval finds, Machine Barn Farm, Longstanton 9 MCB12230 The Manor, Longstanton 10 MCB12231 C13th well, St Michael's Church, Longstanton 11 MCB12232 Site of C13th manor, Longstanton 12 MCB12233 Ridge and furrow, Wilson's Road, Longstanton 13 MCB12235 Headlands at Striplands Farm, Longstanton 14 MCB12236 Ridge and furrow, Longstanton 15 MCB12237 Green End Farm hamlet earthworks 16 MCB12238 Post-medieval earthworks, Longstanton 17 MCB12240 Ridge and furrow, Longstanton 18 MCB12757 Medieval earthworks, Longstanton 19 MCB12799 Ridge and furrow and ponds, Longstanton 20 MCB12801 Ridge and furrow, Green End Farm 21 MCB12989 Enclosures, Cottenham 22 MCB13003 Palaeolithic handaxe, 71 Longstanton Road, Oakington 23 MCB13623 Human remains, Cambridge Road, Oakington 24 MCB13853 Roman coin, Oakington 25 MCB13856 Roman coins find, Longstanton 26 MCB362 Milestone, A14 27 MCB365 Undated skeleton, Dry Drayton 28 MCB395 Site of C15th manor house, Longstanton 29 MCB4118 Fishpond Cottages, Longstanton Medieval churchyard cross, All Saints' Church, 30 MCB4317 Longstanton 31 MCB4327 -

NORTH WEST CAMBRIDGE AREA ACTION PLAN GREEN BELT LANDSCAPE STUDY May 2006

NORTH WEST CAMBRIDGE AREA ACTION PLAN GREEN BELT LANDSCAPE STUDY May 2006 Prepared on behalf of South Cambridgeshire District Council By David Brown BSc(Hons) DipLD MA PhD MIHort FArborA And Richard Morrish BSc(Hons) DipLD MA(LD) MA(Sustainable Development) MLI 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Since 1950, when Professor Holford first recommended that a Cambridge Green Belt be established, the protection of the landscape setting of ‘the only true University town’ in England has been central to the planning of the future growth of the city. The inner boundary of the Green Belt was first defined in 1965 but it was not until 1980 that policy P19/3 of the first Cambridgeshire Structure Plan formally established a Green Belt around Cambridge. However, it was then 1992 before the Cambridge Green Belt achieved full inclusion in the statutory Local Plan. From the outset it has been recognised that the principal purpose of the Cambridge Green Belt is to ‘ preserve the setting and special character of historic towns ’. While the other purposes of including land in the Green Belt clearly apply, they are not the fundamental reason for its existence. The Cambridge Green Belt has been an effective planning mechanism: successful in maintaining a good relationship between the historic core and its rural hinterland and in shaping the growth of the city and its necklace villages while protecting their landscape setting. Cambridge has been a strong growth area for several decades and there is now considerable pressure for further expansion. In the light of this situation a comprehensive review of the Cambridge Green Belt is being undertaken. -

Going for Gold – the South Cambridgeshire Story

Going for gold The South Cambridgeshire story Written by Kevin Wilkins March 2019 Going for gold Foreword Local government is the backbone of our party, and from Cornwall to Eastleigh, Eastbourne to South Lakeland, with directly elected Mayors in Bedford and Watford, Liberal Democrats are making a real difference in councils across the country. So I was delighted to be asked to write this foreword for one of the latest to join that group of Liberal Democrat Jo Swinson MP CBE councils, South Cambridgeshire. Deputy Leader Liberal Democrats Every council is different, and their story is individual to them. It’s important that we learn what works and what doesn’t, and always be willing to tell our story so others can learn. Good practice booklets like this one produced by South Cambridgeshire Liberal Democrats and the Liberal Democrat Group at the Local Government Association are tremendously useful. 2 This guide joins a long list of publications that they have produced promoting the successes of our local government base in places as varied as Liverpool, Watford and, more recently, Bedford. Encouraging more women to stand for public office is a campaign I hold close to my heart. It is wonderful to see a group of 30 Liberal Democrat councillors led by Councillor Bridget Smith, a worthy addition to a growing number of Liberal Democrat women group and council leaders such as Councillor Liz Green (Kingston Upon Thames), Councillor Sara Bedford (Three Rivers) Councillor Val Keitch (South Somerset), Councillor Ruth Dombey (Sutton), and Councillor Aileen Morton (Argyll and Bute) South Cambridgeshire Liberal Democrats are leading the way in embedding nature capital into all of their operations, policies and partnerships, focusing on meeting the housing needs of all their residents, and in dramatically raising the bar for local government involvement in regional economic development. -

South West Cambridge

A VISION FOR South West Cambridge Submitted on behalf of NORTH BARTON ROAD LAND OWNERS GROUP (NORTH BRLOG) February 2020 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 VISION FOR SOUTH WEST CAMBRIDGE 7 Part One BACKGROUND & CONTEXT 9 BACKGROUND & CONTEXT 10 HOUSING NEED 12 HOUSING DELIVERY & MARKET ECONOMICS 12 SITE ANALYSIS 14 Green Belt 16 Landscape & Topography 17 Ecology 18 Noise, Air Quality & Utilities 19 Flood Management 20 Archaeology 21 Heritage 22 Transport 24 Part Two “CAMBRIDGE CLUES” 29 CAMBRIDGE CLUES 31 DEVELOPMENT VISION 32 LANDSCAPE STRATEGY 34 LANDSCAPE & HERITAGE 36 Part Three THE MASTERPLAN & DESIGN STRATEGY 39 THE MASTERPLAN 40 A CITY SCALE LANDSCAPE STRATEGY 46 BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY 54 BENEFICIAL USE OF THE GREEN BELT 56 TRANSPORT OPPORTUNITIES 58 MOVEMENT STRATEGY 60 SUSTAINABILITY 62 A SENSE OF IDENTITY 64 Aldermanne 66 Colys Crosse 68 West View 70 South West Meadows 72 WIDER BENEFITS 73 SUMMARY & CONCLUSIONS 74 2 3 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Vision Document sets out a vision for an exemplar, landscape-led, and highly sustainable new neighbourhood at South West Cambridge. This Vision is based on the key site constraints and opportunities, and a detailed assessment of the following topics: • Green Belt • Landscape and topography • Ecology • Noise, Air Quality & Utilities • Flood Management • Archaeology • Heritage and the setting of the site and the City • Access and transport The Vision is for a new neighbourhood at South West Cambridge that: • Provides between 2,500 and 2,800 high quality new homes with a range of housing types, densities and tenures including market, affordable housing, housing for University and/or College staff, housing for the elderly (including care provision) and student accommodation. -

Green Belt Study 2002

South Cambridgeshire District Council South Cambridgeshire Hall 9-11 Hills Road Cambridge CB2 1PB CAMBRIDGE GREEN BELT STUDY A Vision of the Future for Cambridge in its Green Belt Setting FINAL REPORT Landscape Design Associates 17 Minster Precincts Peterborough PE1 1XX Tel: 01733 310471 Fax: 01733 553661 Email: [email protected] September 2002 1641LP/PB/SB/Cambridge Green Belt Final Report/September 2002 CONTENTS CONTENTS SUMMARY 1.0 INTRODUCTION 2.0 CAMBRIDGE GREEN BELT: PLANNING CONTEXT 3.0 METHODOLOGY 4.0 BASELINE STUDIES Drawings: 1641LP/01 Policy Context: Environmental Designations 1641LP/02 Policy Context: Cultural and Access Designations 1641LP/03 Topography 1641LP/04 Townscape Character 1641LP/05 Landscape Character 1641LP/06 Visual Assessment 5.0 SETTING AND SPECIAL CHARACTER Drawings: 1641LP/07 Townscape and Landscape Analysis 1641LP/08 Townscape and Landscape Role and Function 6.0 QUALITIES TO BE SAFEGUARDED AND A VISION OF THE CITY Drawings: 1641LP/09 Special Qualities to be Safeguarded 1641LP/10 A Vision of Cambridge 7.0 DETAILED APPRAISAL EAST OF CAMBRIDGE Drawings: 1641LP/11 Environment 1641LP/12 Townscape and Landscape Character 1641LP/13 Analysis 1641LP/14 Special Qualities to be Safeguarded 1641LP/15 A Vision of East Cambridge 8.0 CONCLUSIONS Cover: The background illustration is from the Cambridgeshire Collection, Cambridge City Library. The top illustration is the prospect of Cambridge from the east and the bottom illustration is the prospect from the west in 1688. 1641LP/PB/SB/Cambridge Green Belt Final Report/September 2002 SUMMARY SUMMARY Appointment and Brief South Cambridgeshire District Council appointed Landscape Design Associates to undertake this study to assess the contribution that the eastern sector of the Green Belt makes to the overall purposes of the Cambridge Green Belt. -

Hypro Building, Station Rd, Longstanton, Cambrideshire, Cb24 3Ds to Let

PRELIMINARY DETAILS 01223Warehouse 841 841 and office– 9,617 sq ft (893.45 sq m) In Brief ● Part of a larger building of industrial and office accommodation ● Good yard and parking area ● 3 miles from the A14 ● The new Northstowe development nearby HYPRO BUILDING, STATION RD, LONGSTANTON, CAMBRIDESHIRE, CB24 3DS TO LET 01223 841 841 bidwells.co.uk Location Longstanton is a village located 6 miles to the North West of Cambridge. The building is located 1.5 miles away from the new Northstowe Development which will provide over 10,000 new homes to the area. The A14 provides access to Huntingdon and the Midlands and East Coast Ports, as well as the M11 and M25 for Stansted Airport and London. Description The subject premises is of steel portal frame construction with brickwork and profile metal sheet cladding to elevations. The premises benefits from: ● Office and ancillary accommodation ● WC facilities ● Clear eaves height of approximately 3m (up to a maximum of 5.7m) ● 2 Roller shutter doors ● Good yard and parking provisions and Accommodation entrance to the rear sq ft sq m ● An onsite CCTV security system and Office 2,480 230.40 gatehouse Warehouse 7,137 663.05 Total 9,617 893.45 Additional Information Terms Value Added Tax The property is available on a FRI lease with Prices outgoings and rentals are quoted terms to be agreed. Quoting rent available on exclusive of but may be liable to VAT. application. EPC Rates Available upon request Business rates payable are currently calculated from the rateable value of the entire Postcode building. -

Meeting Papers Full Council Meeting, 11Th November 2019

- Longstanton Parish Council Meeting Papers Full Council Meeting, 11th November 2019 LongstantonPC 1 19-20/110 Northstowe Matters a) To receive a report following the Community Forum held on 6th November 2019 at the new Northstowe Secondary School. b) To receive an update on Northstowe matters from Jon London, Community Project Officer. 19-20/111 Finance Matters a) To receive an update on the financial position of the council from the Clerk. b) The Clerk noted that the Precept Request letter had been received from South Cambs District Council (appendix 1). It is asked whether the Parish Council wishes to comment on the consultation in Appendix A of the document and if so, a response is required by 18th November 2019. The Clerk noted that there is nothing significantly different to previous years when LPC have not made any comment. c) The Clerk noted that some tree work is required to Council trees following the survey carried out in March 2018 by Acacia Tree Surgery. The Clerk has approached Brookfield Groundcare (appendix 2) to get comparative costs to those provided by Acacia listed below: Acacia £4,130 Brookfield Groundcare £3,470 Recommendation: to employ Brookfield Groundcare to carry out the tree work as it is both more cost effective and they have itemised some additional work to be undertaken which has developed since the time of the survey in 2018. 19-20/112 Planning Matters (links to all planning applications can be found on the website: http://www.longstanton-pc.gov.uk/Planning_Applications_22977.aspx) a) Presentation to be made by Quinton Carroll from Cambridgeshire County Council about an application for a shared Heritage Facility between Northstowe, Longstanton and A14. -

Longstanton Life Volume 20, Issue No

Longstanton Life Volume 20, Issue No. 2 April - May 2020 Life in Your Locality d d u R a n n A y b o t o h P . s l i d o ff a D The information in The Longstanton Life is provided in good faith and we have tried to ensure that it is accurate and correct. However, neither the editorial team nor the contributors can be held responsible for any inaccuracies or omissions or any consequential losses of any form whatsoever arising therefrom. The editorial team for this edition were: Anna Rudd, Tony Cowley, Manjeet Bolla, Beth Baker, Tracy Cole, Georgie Edwards and John Pratt . The Longstanton Life newsletter is Copyright © 2000 - 2020 The Editorial Team. All Rights Reserved. Editorial graphics © LLife V I L L AG E D I A RY DUE TO CORONAVIRUS PLEASE CHECK WITH THE ORGANISER FIRST SUNDAY 0930-1030 Sunday School Village Institute* Susan Meah 01954 781258 1100 Tennis Club Sessions The Pavilion Sarah Ballard 07985 938959 MONDAY 1100-1200 Zumba Gold Village Institute* Davina Mee 07779 244250 1800-2000 Bowls Club The Pavilion Marion Edwards 01954 780118 1930-2030 Jazzercise Hatton Park School Tina Chasse 01487 841811 2nd of month 1930 Parish Council Village Institute* (Open meeting) 3rd of month 1945 W.I. Village Institute* Patrizia Peters 01954 781283 TUESDAY 1000-1200 Coffee morning (over 55's) The Dale Comm. Hall Please just turn up 1030-1115 Mini JAFFAs (pre-schoolers) All Saints’ Church Susan Meah 01954 781258 1700-2000 Tennis - Junior and adult coaching The Pavilion [email protected] 1830-2000 Adult Cricket training (May-August) Recreation Ground Wayne Markillie 07737 313225 1900-1945 SRF Bootcamp Recreation Ground Shane Rackham 07912 555301 1900-2100 Cambridge Freestyle Martial Arts Village Institute* Rory / Martin 07523 854251 / 07535 646234 1900-2130 ATC (Air Training Corps) Cadet Centre WEDNESDAY 1000-1100 Music Madness (0-5yrs) Village Institute* Sharon Sennitt 07762 206320 1800 Tennis Club Night The Pavilion Sarah Ballard 07985 938959 1910-2130 Army Cadet Force (12-18yrs) Cadet Centre Sgt. -

Bar Hill Longstanton Willingham Over Swavesey 5 | 5A

Bar Hill Longstanton Willingham Over Swavesey 5 | 5A MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS (excluding Bank Holidays) 5A 5A 5A 5A 5A Over City Centre Emmanuel Street E4 - 0930 1130 1330 1510 Willingham Girton Corner - 0942 1142 1342 1522 Bar Hill Shopping Centre - 0954 1154 1354 1544 interchange point Trn Trn Trn Trn Bar Hill Shopping Centre - 1005 1205 1405 1605 Longstanton Church - 1012 1212 1412 1612 Longstanton Park & Ride - 1018 1218 1418 1618 Longstanton Swavesey Willingham Willford Furlong - 1025 1225 1425 1625 Park & Ride Over Green - 1035 1235 1435 1635 Swavesey Middle Watch 0841 1042 1242 1442 1642 Longstanton Park & Ride 0849 1051 1251 1451 1651 Longstanton Church 0852 1054 1254 1454 1654 Longstanton Bar Hill Shopping Centre 0859 1101 1301 1501 1701 interchange point Trn Trn Trn Trn Trn Bar Hill Shopping Centre 0915 1115 1315 1525 1705 Bar Hill Bar Hill Appletrees 0921 1121 1321 1533 1711 Girton Corner 0930 1130 1330 1543 1721 City Centre Emmanuel Street E4 0946 1146 1346 1604 1744 SATURDAYS (excluding Bank Holidays) 5A 5A 5A 5A 5A City Centre Emmanuel Street E4 - 0930 1120 1320 1520 Girton Corner - 0944 1134 1334 1534 Bar Hill Shopping Centre - 0954 1149 1349 1549 interchange point Trn Trn Trn Trn Bar Hill Shopping Centre - 1005 1205 1405 1605 Longstanton Church - 1012 1212 1412 1612 Longstanton Park & Ride - 1018 1218 1418 1618 Willingham Willford Furlong - 1025 1225 1425 1625 Over Green - 1035 1235 1435 1635 Swavesey Middle Watch 0826 1042 1242 1442 1642 Longstanton Park & Ride 0834 1051 1251 1451 1651 Longstanton Church 0837 1054 1254 1454 1654 Bar Hill Shopping Centre 0844 1101 1301 1501 1701 interchange point Trn Trn Trn Trn Trn Bar Hill Shopping Centre 0855 1115 1315 1515 1715 KEY Bar Hill Appletrees 0900 1120 1320 1520 1720 Transfer at Bar Hill for all journeys to and Girton Corner 0910 1130 1330 1530 1730 Trn from Cambridge. -

![Site Assessment Rejected Sites Broad Location 8 [PDF, 0.8MB]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8494/site-assessment-rejected-sites-broad-location-8-pdf-0-8mb-2678494.webp)

Site Assessment Rejected Sites Broad Location 8 [PDF, 0.8MB]

Site Assessments of Rejected Green Belt Sites for Broad Location 8 500 Cambridge City Council / South Cambridgeshire District Council Green Belt Site and Sustainability Appraisal Assessment Proforma Site Information Broad Location 8 Land east of Gazelle Way Site reference number(s): SC296 Site name/address: Land east of Gazelle Way Functional area (taken from SA Scoping Report): City only Map: Site description: Large flat arable fields with low boundary hedges to Gazelle Way. Woodland belt adjoins Cherry Hinton Road, more significant hedges elsewhere. Suburban residential to west of Gazelle Way. Major electricity transformer station to south at junction of Gazelle Way and Fulborn Old Drift with two lines of pylons, one high, metal pylon line to eastern field boundary and a second double line of lower power, wooden pylons crosses the middle of the site. Tesco supermarket to south. Prefab housing site adjoins Fulbourn Old Drift to the east. The land very gently falls away towards the east. Current use: Agricultural Proposed use(s): Residential Site size (ha): 21 approximately Assumed net developable area: 10.5 approximately Assumed residential density: 40 dph Potential residential capacity: 420 Site owner/promoter: Known Landowner has agreed to promote site for development?: Landowners appear to support development Site origin: Green Belt assessment 501 Relevant planning history: Planning permission granted in 1981 for land fronting onto the northern half of Gazelle Way for housing development, open space and schools. A subsequent planning permission in 1985 limited built development to the west of Gazelle Way only, which was implemented. The Panel Report into the draft Cambridgeshire & Peterborough Structure Plan published in February 2003 considered proposals for strategic large scale development to the east of Cambridge Airport around Teversham and Fulbourn. -

A14 Cambridge to Huntingdon Improvement Scheme Closure of the A14 at Bar Hill (Junction 29)

A14 Cambridge to Huntingdon improvement scheme Closure of the A14 at Bar Hill (junction 29) Friday 14 September (9pm) to Monday 17 September (6am) What are we doing? We’re installing two new bridges as part of the new junction at Bar Hill. These bridges will eventually form part of the new roundabout and improved Bar Hill junction. Each of the bridge decks is 44 metres long and weighs 1,000 tonnes. We will bring the steel and concrete bridge decks along the A14 from their fabrication yard next to the junction (where they have been assembled). We will then lift them into place on their new piers using a special transporter. There is no space to safely watch the work taking place, but we will live-stream the work and share a time-lapse video soon afterwards. A link to the live-stream will be shared on our website and social media pages. To prepare for this very special operation, which is the quickest way to install the two new bridges, we need to close the A14 and make some temporary changes to the slip roads at Bar Hill. The closure is essential for the construction of the new Bar Hill junction. We apologise for the inconvenience that this will cause. How will this affect your journey? BAR HILLBar JUNCTION Hill slip 29 road closure and diversion route 14-09-18 to 16-09-18 BAR HILL JUNCTION 29 TOWARDS 14-09-18 to 16-09-18 Road closed LONGSTANTON Into Bar hill You will not be able to travel Out of Bar Hill TOWARDS Road closed LONGSTANTON through the Bar Hill junction Into Bar hill along the A14 in either TOWARDS Out of Bar Hill CAMBRIDGE direction.