Active Mobility Every Day

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walking and Cycling Interactions on Shared-Use Paths

Walking and Cycling Interactions on Shared-Use Paths Hannah Delaney A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol, for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Faculty of Environment and Technology, University of the West of England, Bristol, UK February 2016 Abstract Central to this research are the interactions that take place between cyclists and pedestrians on shared-use paths and the impact of these on journey experiences. This research proposes that as active travel is promoted and as walking and cycling targets are set in the UK, there is a potential for levels of active travel to increase; putting pressure on shared-use paths, and potentially degrading journey experiences. Previous research on shared-use paths focuses on the observable aspects of shared path relations, such as visible collisions and conflict. However, this thesis suggests that it is necessary to investigate shared-path interactions in more depth, not only focusing on the visible signs of conflict but also examining the non-visible experiential interactions. Thus, this research addresses the following questions: - What are the different kinds of interactions that occur on shared-use paths? - How do path users experience and share the path? - What are the respondents’ expectations and attitudes towards the path? - What are the practice and policy options in relation to enhancing shared-path experiences? - Are video recordings a useful aid to in-depth interviews? The Bristol-Bath railway path (Bristol, UK) was chosen as a case study site and a two phased data collection strategy was implemented. Phase I included on-site intercept surveys with cyclists and pedestrians along the path. -

From Fitness Zones to the Medical Mile

From Fitness Zones to the Medical Mile: How Urban Park Systems Can Best Promote Health and Wellness Related publications from The Trust for Public Land The Excellent City Park System: What Makes It Great and How to Get There (2006) The Health Benefits of Parks (2007) Measuring the Economic Value of a City Park System (2009) Funding for this project was provided by The Ittleson Foundation, New York, New York PlayCore, Inc., Chattanooga, Tennessee The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, New Jersey U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia About the authors Peter Harnik is director of The Trust for Public Land’s Center for City Park Excellence and author of Urban Green: Innovative Parks for Resurgent Cities (Island Press, 2010). Ben Welle is assistant project manager for health and road safety at the World Resources Institute. He is former assistant director of the Center for City Park Excellence and former editor of the City Parks Blog (cityparksblog.org). Special thanks to Coleen Gentles for administrative support. The Trust for Public Land Center for City Park Excellence 660 Pennsylvania Ave. SE Washington, D.C. 20003 202.543.7552 tpl.org/CCPE © 2011 The Trust for Public Land Cover photos: Darcy Kiefel From Fitness Zones to the Medical Mile: How Urban Park Systems Can Best Promote Health and Wellness By Peter Harnik and Ben Welle TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 1. A MIXTURE OF USES AND A MAXIMUM AMOUNT OF PROGRAMMING 6 Cincinnati Recreation Commission 8 Fitness Zones, Los Angeles 9 Urban Ecology Center, Milwaukee 10 2. STRESS REDUCTION: CALMING TRAFFIC AND EMOTIONS 12 Golden Gate Park, San Francisco 15 Sunday Parkways, Portland, Oregon 17 Seattle’s P-Patch 18 Patterson Park, Baltimore 20 3. -

ACE Walking Toolkit

The American Council on Exercise (ACE), a leading non-profit health and fitness organization, is dedicated to ensuring that individuals have access to well-qualified health and fitness professionals, as well as science-based information and resources on safe and effective physical activity. Ultimately, we want to empower all Americans to be active, establish healthy behaviors and live their most fit lives. ACE envisions a world in which obesity and other preventable lifestyle diseases are on the decline because people have been understood, educated, empowered, and granted responsibility to be physically active and committed to healthy choices. We are excited that the Surgeon General used the influence of his position to draw attention to physical inactivity—a critical public health issue—and to create a pathway to change the sedentary culture of this nation through his introduction of Step It Up! The Surgeon General’s Call to Action on Walking and Walkable Communities. ACE strongly supports this emphasis on walking and walkable communities as part of our mission and commitment to fighting the dual epidemics of obesity and inactivity, and creating a culture of health that values and supports physically active lifestyles. But we know that we can’t accomplish our mission alone. Creating a culture of health will require the focus of policymakers, the dedication of fitness professionals, and the commitment of individuals to live sustainable, healthy lifestyles. This toolkit is a demonstration of our commitment to support the landmark Call to Action. It has been designed to help fitness professionals “Step It Up!” and lead safe and effective walking programs, and become advocates for more walkable communities. -

Watch and Learn Maines

Watch and Learn Maines Watch and Learn How observation can enhance understanding of walkability and bikability around transit stations Option Paper Kat Maines Advisor: Brian Stone, Ph.D. 04.21.2016 1 Watch and Learn Maines Contents I. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 5 II. Literature Review ................................................................................................... 7 A. What’s the problem with first and last mile connectivity around transit stations? .......................................................................................................................... 7 B. What are the elements of a complete and high quality first and last mile network? .......................................................................................................................... 9 i. Sidewalks and paths ........................................................................................ 10 ii. Elements of an interesting walking environment ......................................... 10 iii. Bike Lanes ........................................................................................................ 11 iv. End of trip facilities and transit accommodations ......................................... 12 v. Bike share ......................................................................................................... 12 vi. Traffic calming ................................................................................................. -

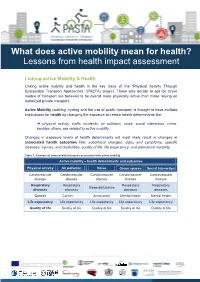

What Does Active Mobility Mean for Health? Lessons from Health Impact Assessment

What does active mobility mean for health? Lessons from health impact assessment Linking active Mobility & Health Linking active mobility and health is the key issue of the “Physical Activity Through Sustainable Transport Approaches” (PASTA) project. Those who decide to opt for active modes of transport are believed to be overall more physically active than those relying on motorized private transport. Active Mobility (walking, cycling and the use of public transport) is thought to have multiple implications for health by changing the exposure to certain health determinants like: physical activity, traffic incidents, air pollution, noise, social interaction, crime, besides others, are related to active mobility. Changes in exposure levels of health determinants will most likely result in changes in associated health outcomes like: subclinical changes, signs and symptoms, specific diseases, injuries, and disabilities, quality of life, life expectancy, and premature mortality. Table 1: Example of some health outcomes associated with active mobility Active mobility – health determinants and outcomes Physical activity Air pollution Noise Green spaces Social interaction Cardiovascular Cardiovascular Cardiovascular Cardiovascular Cardiovascular disease disease disease disease disease Respiratory Respiratory Respiratory Respiratory Sleep distubance diseases diseases diseases diseases Cancer Cancer Annoyance Mental health Mental health Life expectancy Life expectancy Life expectancy Life expectancy Life expectancy Quality of life Quality of life Quality of life Quality of life Quality of life This project has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme for research; technological development and demonstration under grant agreement no 602624-2. Benefits one translates into benefits for all! The uptake of active mobility impacts not only the health determinants of individual travelers who decide to walk, cycle or use public transport, but also for society as a whole. -

Cycling to Work: Not Only a Utilitarian Movement but Also an Embodiment of Meanings and Experiences That Constitute Crucial

Conclusion This research analysed the different facets of utility cycling in Switzerland, using the example of commuting. We took as our starting point the concept of the cycling system, or velomobility, which underlines the importance of taking into account all elements—not only material and technical but also social, political and symbolic— which influence this practice. From this perspective, we argued that cycling—in terms of volume, frequency, distance, motivation, etc.—depends on the coming together of two potentials. The first of these is motility [11–13] or, more precisely, the indi- viduals’ cycling potential. It is built around access (‘to be able to’ use a means of transport), skills ((‘to know how to’ cycle for utility reasons) and appropriation (‘to want to’ cycle). Individuals’ appropriation of cycling depends on their perception of that mode and of its particularities, which can be interpreted as a confluence of three fundamental dimensions of mobility: movement, meaning and experience in a context of power in regards to the dominant system of automobility [6]. The second of the two potentials is the territory’s hosting potential, or its degree of bikeability, which relates to the spatial context, the available infrastructure and amenities (bicycle urbanism), as well as social and legal norms and rules. In order to identify a large sample of bicycle commuters, we focused on the bike to work scheme, which each year brings together people who commit to cycling to their place of work as often as possible during the months of May and/or June. Nearly 14,000 people completed an online questionnaire addressing the dimensions of velomobility. -

Homeless Campaigns, & Shelter Services in Boulder, Colorado

Dreams of Mobility in the American West: Transients, Anti- Homeless Campaigns, & Shelter Services in Boulder, Colorado Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrew Lyness, M.A. Graduate Program in Comparative Studies The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Leo Coleman, Advisor Barry Shank Theresa Delgadillo Copyright by Andrew Lyness 2014 Abstract For people living homeless in America, even an unsheltered existence in the urban spaces most of us call “public” is becoming untenable. Thinly veiled anti-homelessness legislation is now standard urban policy across much of the United States. One clear marker of this new urbanism is that vulnerable and unsheltered people are increasingly being treated as moveable policy objects and pushed even further toward the margins of our communities. Whilst the political-economic roots of this trend are in waning localism and neoliberal polices that defined “clean up the streets” initiatives since the 1980s, the cultural roots of such governance in fact go back much further through complex historical representations of masculinity, work, race, and mobility that have continuously haunted discourses of American homelessness since the nineteenth century. A common perception in the United States is that to be homeless is to be inherently mobile. This reflects a cultural belief across the political spectrum that homeless people are attracted to places with lenient civic attitudes, good social services, or even nice weather. This is especially true in the American West where rich frontier myths link notions of homelessness with positively valued ideas of heroism, resilience, rugged masculinity, and wilderness survival. -

The Vagrant Spaces of the Malls, Enclave Estates, the Filmic and the Televisual

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 1-1-2001 Imagineering the community: The vagrant spaces of the malls, enclave estates, the filmic and the televisual Dennis Wood Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Wood, D. (2001). Imagineering the community: The vagrant spaces of the malls, enclave estates, the filmic and the televisual. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1029 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1029 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Active Mobility in Singapore 19 Walking and Cycling in the Tropics

Creating Healthy Places Through Active Mobility 105 © 2014 Centre for Liveable Cities and Urban Land Institute. All rights reserved. Printed on Enviro Wove, an FSC Mix Credit Certified Paper ISBN 978-981-09-2479-9 (print) ISBN 978-981-09-2480-5 (e-book) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Every effort has been made to trace all sources and copyright holders of news articles, figures, and information in this book before publication. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, CLC and ULI will ensure that full credit is given at the earliest opportunity. The e-book can be accessed at http://clc.gov.sg/documents/books/active_ mobility/index.html 4 Creating Healthy Places Through Active Mobility Creating Healthy Places Through Active Mobility 5 FOREWORD Cities are for people to live and enjoy. But A bolder plan is to support inter-town cycling. From the pressures on physical infrastructure of the Institute’s global networks to shape some cities are more liveable than others, This will be more challenging. Amsterdam such as transport, housing and public space projects and places in ways that improve the as a result of forward planning and sound took decades to wean off their attachment to through to intangible challenges such as health of people and communities. implementation. private cars and acquire a wonderful culture securing economic competitiveness and of walking and cycling. -

Giving Parks Back to People: Increasing the Bikeability and Walkability of New Orleans City Park

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Planning and Urban Studies Reports and Presentations Department of Planning and Urban Studies Spring 2009 Giving Parks Back to People: Increasing the Bikeability and Walkability of New Orleans City Park Department of Planning and Urban Studies, University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/plus_rpts Part of the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Department of Planning and Urban Studies, University of New Orleans, "Giving Parks Back to People: Increasing the Bikeability and Walkability of New Orleans City Park" (2009). Planning and Urban Studies Reports and Presentations. Paper 6. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/plus_rpts/6 This Study is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Planning and Urban Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Planning and Urban Studies Reports and Presentations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Giving Parks Back to People Increasing the Walkability and Bikeability of New Orleans City Park Photo Source: http://outdoors.webshots.com/photo/1066350157045045291QfGdBS Applied Techniques of Transportation Planning Brian Baldwin Fabian Ballard Rosanna Ballinger MURP 4062; Spring 2009 James BentleyJohn JarvisColeen Judge Dr. John Renne, Assistant Professor of Chandra LillyMichelle LittleNicole McCall Transportation Studies and Urban Planning Ross Reahard Chelsea ShellingLevi Stewart Department of Planning and Urban Studies University of New Orleans MURP 4062 Applied Transportation Planning Spring 2009 Table of Contents Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………………………………….……….iii Chapter One Introduction and Background…………………………………………………………………1 1. History of New Orleans City Park…………………………………………………..... 3 2. City Park Today……………………………………………………………………….. -

Walking Fast Author: Iknoian, Therese. Publisher

title: Walking Fast author: Iknoian, Therese. publisher: Human Kinetics isbn10 | asin: 0880116617 print isbn13: 9780880116619 ebook isbn13: 9780585248073 language: English subject Fitness walking, Walking (Sports) publication date: 1998 lcc: GV502.I45 1998eb ddc: 613.7/176 subject: Fitness walking, Walking (Sports) Page iii Walking Fast Therese Iknoian Human Kinetics Page iv Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Iknoian, Therese, 1957 Walking fast / Therese Iknoian. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. 169) and index, ISBN 0-88011-661-7 1. Fitness walking 2. Walking (Sports) I. Title. GV502.145 1998 613.7'176dc21 97-38947 CIP ISBN: 0-88011-661-7 Copyright © 1998 by Therese Iknoian All rights reserved. Except for use in a review, the reproduction or utilization of this work in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including xerography, photocopying, and recording, and in any information storage and retrieval system, is forbidden without the written permission of the publisher. Permission notices for material reprinted in this book from other sources can be found on page xiii. Developmental Editor: Marni Basic; Assistant Editor: Henry V. Woolsey; Copyeditor: Jim Burns; Proofreader: Erin Cler; Indexer: Prottsman Indexing; Graphic Designer: Nancy Rasmus; Graphic Artist: Angela K. Snyder; Photo Editor: Boyd LaFoon; Cover Designer: Jack Davis; Photographer (cover): © Tony Stone Images/Brian Bailey; Photographer (Interior): Ken Lee, except where noted; Illustrators: Paul To and Joe Bellis; Printer: United Graphics Human Kinetics books are available at special discounts for bulk purchase. Special editions or book excerpts can also be created to specification. For details, contact the Special Sales Manager at Human Kinetics. -

Leisure Experiences in Nordic Walking and Rambling, And

LEISURE EXPERIENCES IN NORDIC WALKING AND RAMBLING, AND THEIR CONTRIBUTIONS TO MENTAL WELL-BEING: A MIXED-METHODS STUDY Marta Anna Zurawik A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Bolton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2017 University of Bolton TABLE OF CONTENT Abstract ...................................................................................................................................v Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................... vii List of tables ......................................................................................................................... ix List of figures ..................................................................................................................... xiv List of pictures ................................................................................................................... xvi Chapter 1. Introduction to the study .................................................................................1 1.1. Walking for leisure – spectrum of recreational options ................................................7 1.2. A role of place in leisure walking and benefits for well-being .....................................10 1.3. Nordic walking as a new form of leisure walking ........................................................20 1.4. Conceptual framework of the study ..............................................................................26