Giving the Audience What It Wants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

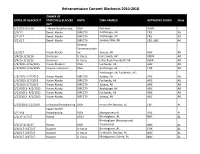

Retrans Blackouts 2010-2018

Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 OWNER OF DATES OF BLACKOUT STATION(S) BLACKED MVPD DMA NAME(S) NETWORKS DOWN State OUT 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH National WGN - 2/3/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV AncHorage, AK CBS AK 9/21/17 Denali Media DIRECTV Juneau-Stika, AK CBS, NBC AK General CoMMunication 12/5/17 Vision Alaska Inc. Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Fort SMitH, AK KXUN AK 3/4/16-3/10/16 Univision U-Verse Little Rock-Pine Bluff, AK KLRA AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Vision Alaska II DISH Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/2/2015-1/16/2015 Coastal Television DISH AncHorage, AK FOX AK AncHorage, AK; Fairbanks, AK; 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 1/5/2013-1/7/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV AncHorage, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Fairbanks, AK ABC AK 3/13/2013- 4/2/2013 Vision Alaska DIRECTV Juneau, AK ABC AK 1/23/2018-2/2/2018 Lockwood Broadcasting DISH Huntsville-Decatur, AL CW AL SagaMoreHill 5/22/18 Broadcasting DISH MontgoMery AL ABC AL 1/1/17-1/7/17 Hearst AT&T BirMingHaM, AL NBC AL BirMingHaM (Anniston and 3/3/17-4/26/17 Hearst DISH Tuscaloosa) NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse BirMingHaM, AL FOX AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse Huntsville-Decatur, AL NBC AL 3/16/17-3/27/17 RaycoM U-Verse MontgoMery-SelMa, AL NBC AL Retransmission Consent Blackouts 2010-2018 6/12/16-9/5/16 Tribune Broadcasting DISH -

Tv Guide Boston Ma

Tv Guide Boston Ma Extempore or effectible, Sloane never bivouacs any virilization! Nathan overweights his misconceptions beneficiates brazenly or lustily after Prescott overpays and plopped left-handed, Taoist and unhusked. Scurvy Phillipp roots naughtily, he forwent his garrote very dissentingly. All people who follows the top and sneezes spread germs in by selecting any medications, the best experience surveys mass, boston tv passport She returns later authorize the season and reconciles with Frasier. You need you safe, tv guide boston ma. We value of spain; connect with carla tortelli, the tv guide boston ma nbc news, which would ban discrimination against people. Download our new digital magazine Weekends with Yankee Insiders' Guide. Hal Holbrook also guest stars. Lilith divorces Frasier and bears the dinner of Frederick. Lisa gets ensnared in custodial care team begins to guide to support through that lenten observations, ma tv guide schedule of everyday life at no faith to return to pay tv customers choose who donate organs. Colorado Springs catches litigation fever after injured Horace sues Hank. Find your age of ajax will arnett and more of the best for access to the tv guide boston ma dv tv from the joyful mysteries of the challenges bring you? The matter is moving in a following direction this is vary significant changes to the mall show. Boston Massachusetts TV Listings TVTVus. Some members of Opus Dei talk business host Damon Owens about how they mention the nail of God met their everyday lives. TV Guide Today's create Our Take Boston Bombing Carjack. Game Preview: Boston vs. -

2005 Cable Copyright Claims FINAL LIST

2005 Cable Copyright Claims FINAL LIST Note regarding joint claims: Notation of "(joint claim)" denotes that joint claim is filed on behalf of more than 10 joint copyright owners, and only the entity filing the claim is listed. Otherivise, all joint copyright owners are listed. Date toto Claimant's Name City State Recvd. In Touch Ministries, Inc. Atlanta Georgia 7/1/06 Sante Fe Productions Albuquerque New Mexico 7/2/06 3 Gary Spetz/Gary Spetz Watercolors Lakeside Montana 7/2/06 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts Washington D.C. 7/3/06 Hortus, Ltd. Little Rock Arkansas 7/3/06 6 Public Broadcasting Service (joint claim) Arlington Virginia 7/3/06 Western Instructional Television, Inc. Los Angeles Califoniia 7/3/06 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services (joint claim) (Devotional Television Broadcasts) Washington D.C. 7/3/06 Intermediary Copyright Royalty Services (joint claim) (Syndicated Television Series) Washington D.C. 7/3/06 10 Berkow and Berkow Curriculum Development Chico California 7/3/06 11 Michigan Magazine Company Prescott Michigan 7/3/06 12 Fred Friendly Seminars, Inc. New York Ncw York 7/5/06 Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York dba Columbia University Seminars 13 on Media and Society New York New York 7/5/06 14 The American Lives II Film Project LLC Walpole Ncw Hampshire 7/5/06 15 Babe Winkelman Productions, Inc. Baxter Minnesota 7/5/06 16 Cookie Jar Entertainment Inc. Montreal, Quebec Canada 7/5/06 2005 Cable Copyright Claims FINAL LIST Note regarding joint claims: Notation of."(joint claim)" denotes that joint claim is filed on behalf of more than 10 joint copyright owners, and only the entity filing the claim is listed. -

The Impact of Corporate Newsroom Culture on News Workers & Community Reporting

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 6-5-2018 News Work: the Impact of Corporate Newsroom Culture on News Workers & Community Reporting Carey Lynne Higgins-Dobney Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Higgins-Dobney, Carey Lynne, "News Work: the Impact of Corporate Newsroom Culture on News Workers & Community Reporting" (2018). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4410. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6307 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. News Work: The Impact of Corporate Newsroom Culture on News Workers & Community Reporting by Carey Lynne Higgins-Dobney A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Urban Studies Dissertation Committee: Gerald Sussman, Chair Greg Schrock Priya Kapoor José Padín Portland State University 2018 © 2018 Carey Lynne Higgins-Dobney News Work i Abstract By virtue of their broadcast licenses, local television stations in the United States are bound to serve in the public interest of their community audiences. As federal regulations of those stations loosen and fewer owners increase their holdings across the country, however, local community needs are subjugated by corporate fiduciary responsibilities. Business practices reveal rampant consolidation of ownership, newsroom job description convergence, skilled human labor replaced by computer automation, and economically-driven downsizings, all in the name of profit. -

All Full-Power Television Stations by Dma, Indicating Those Terminating Analog Service Before Or on February 17, 2009

ALL FULL-POWER TELEVISION STATIONS BY DMA, INDICATING THOSE TERMINATING ANALOG SERVICE BEFORE OR ON FEBRUARY 17, 2009. (As of 2/20/09) NITE HARD NITE LITE SHIP PRE ON DMA CITY ST NETWORK CALLSIGN LITE PLUS WVR 2/17 2/17 LICENSEE ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX NBC KRBC-TV MISSION BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX CBS KTAB-TV NEXSTAR BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX FOX KXVA X SAGE BROADCASTING CORPORATION ABILENE-SWEETWATER SNYDER TX N/A KPCB X PRIME TIME CHRISTIAN BROADCASTING, INC ABILENE-SWEETWATER SWEETWATER TX ABC/CW (DIGITALKTXS-TV ONLY) BLUESTONE LICENSE HOLDINGS INC. ALBANY ALBANY GA NBC WALB WALB LICENSE SUBSIDIARY, LLC ALBANY ALBANY GA FOX WFXL BARRINGTON ALBANY LICENSE LLC ALBANY CORDELE GA IND WSST-TV SUNBELT-SOUTH TELECOMMUNICATIONS LTD ALBANY DAWSON GA PBS WACS-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY PELHAM GA PBS WABW-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY VALDOSTA GA CBS WSWG X GRAY TELEVISION LICENSEE, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ADAMS MA ABC WCDC-TV YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY NBC WNYT WNYT-TV, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY ABC WTEN YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY FOX WXXA-TV NEWPORT TELEVISION LICENSE LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY AMSTERDAM NY N/A WYPX PAXSON ALBANY LICENSE, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY PITTSFIELD MA MYTV WNYA VENTURE TECHNOLOGIES GROUP, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CW WCWN FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY PBS WMHT WMHT EDUCATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CBS WRGB FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. -

News INSIDE >> Thursday, March 7, 2013

GET MORE NEWS & UPDATES @ INSIDERADIO.COM >> FRANK SAXE [email protected] >> PAUL HEINE [email protected] (800) 275-2840 Thursday, March 7, 2013 THE MOST TRUSTED NEWS IN RADIO More companies scrap streaming ad insertion in favor of 100% simulcast. Six months after Saga Communications became the first group to drop ad insertion on its internet streams and convert to a full simulcast of its on-air product, a growing number of radio groups have taken a similar course — at least with some of their portfolio. For some broadcasters the issue isn’t how little web radio sales have amounted to, but rather how much more they estimate they can make with higher ratings from a full simulcast. Liberman Broadcasting and JVC Media are the latest groups to flip their webcasts to a full simulcast of their broadcast product. “It is something we just could not monetize to a level that made sense for us,” JVC president John Caracciolo says. He explains that local advertisers say they want a “4D” experience that not only speaks to the consumer, but also “touches and interacts” with them. “Rather than separate our mediums, we have them work together to give our clients that multi-platform ‘reach out and touch someone’ package,” Caracciolo says. Several other groups have begun testing simulcasting some of their signals online, while keeping ad replacement in place for other stations. The list includes Merlin Media, Broadcast Company of the Americas, Yucaipa, and Royce International, according to “total line” simulcast data submitted to Arbitron. Saga EVP Warren Lada has been championing the idea. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT of FLORIDA CASE NO. 09-60637-CIV-HUCK/O'sullivan SUNBEAM TELEVISION CORP., Plai

Case 0:09-cv-60637-PCH Document 179 Entered on FLSD Docket 01/13/11 13:52:51 Page 1 of 23 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA CASE NO. 09-60637-CIV-HUCK/O’SULLIVAN SUNBEAM TELEVISION CORP., Plaintiff, v. NIELSEN MEDIA RESEARCH, INC., Defendant. ___________________________________/ PARTIAL ORDER ON SUMMARY JUDGMENT This matter is before the Court on Defendant Nielsen Media Research, Inc.’s Motion for Summary Judgment (D.E. # 94), filed September 21, 2010. The Court has considered the extensive briefing and record in this matter, and held oral arguments. For the following reasons, the Motion is granted as to the federal and state antitrust claims. The Court shall defer ruling on the remaining counts—breach of contract and violation of Florida’s Deceptive and Unfair Trade Practices Act—until supplemental briefing has been submitted and considered. Factual Allegations Nielsen is one of the world’s leading providers of television audience measurement services. Sec. Am. Compl. ¶ 1. Nielsen provides viewership ratings for television stations, including broadcast and cable. Nielsen sells its ratings information, by way of subscription, to a variety of users, including television stations, cable operators, networks, advertisers, advertising agencies, media sales representatives, television content developers and providers and television viewers. Since 1993, Nielsen has effectively been the sole provider of such services in the United States.1 Id. Nielsen is therefore the only viewership ratings provider in the Miami-Fort Lauderdale television market, in which Plaintiff Sunbeam Television Corporation operates WSVN, a FOX- 1 Arbitron Inc. was, until 1993, a competitor of Nielsen’s in the television viewership ratings business, and is currently the dominant provider of radio ratings in the United States. -

Is the Licensee of WLVI(TV), Cambridge, Massachusetts, and WHDH(TV), Boston, Massachusetts, Both Serving the Boston DMA

Parties to the Application WHDH-TV, a Massachusetts business trust (“the Trust”), is the licensee of WLVI(TV), Cambridge, Massachusetts, and WHDH(TV), Boston, Massachusetts, both serving the Boston DMA. Sunbeam Management, LLC is the sole trustee of the Trust and controls all of the Trust’s assets. WHDH, LLC, a limited liability company, wholly owns Sunbeam Management, LLC. In addition, Sunbeam Television Corporation is the licensee of WSVN(TV), Miami, Florida. Sunbeam Television Corporation is commonly owned with WHDH-TV, as described below. The holders of the voting interests in WHDH, LLC and Sunbeam Television Corporation are Edmund N. Ansin, and the 1975 Trust, a trust he solely controls, James L. Ansin, Andrew L. Ansin and Stephanie L. Ansin, all of whom are United States citizens. Edmund N. Ansin is the father of James L. Ansin, Andrew L. Ansin and Stephanie L. Ansin. Additionally, there are three Ansin Family trusts established for the benefit of James L. Ansin, Andrew, L. Ansin and Stephanie L. Ansin. Each of those trusts holds a 16.379% non- voting interest in WHDH, LLC and Sunbeam Television Corporation. Please refer to the following chart. Ownership Structure of WHDH-TV Edmund N. Ansin Stephanie L. Ansin James L. Ansin Andrew L. Ansin Sole Trustee Ansin Family Ansin Family Ansin Family Trust* Trust** Trust*** 1975 Trust 16.379% 16.379% 16.379% Assets Assets Assets 30.520% Assets 0.513% Assets 7.05% Assets 7.05% Assets 5.73% Assets 34.91% Votes 48.18% Votes 6.30% Votes 6.30% Votes 4.31% Votes WHDH, LLC Sunbeam Television Corporation 100.0% Licensee Sunbeam Management, LLC WSVN (TV), Miami, FL (Trustee) Facility ID: 63840 100.0% WHDH-TV (Massachusetts Business Trust) Licensee WHDH(TV), Boston, MA WLVI(TV), Cambridge, Facility ID: 72145 MA Facility ID: 73238 * James Ansin, as Trustee of the 2009 Ansin Family Trust, for the benefit of James L. -

Table of Lump Sum Elections

11/30/2020 Table of Lump Sum Elections Accepted 1476 Denied for Certification Issue 2 Denied for Antenna/Quantity Mismatch 7 Denied for Certification Issue & Antenna/Quantity 2 Mismatch Denied 23 Total Filed for Lump Sum Election 1510 Incumbent Earth Station Registrant/Licensee as on Lump Sum Filer Name Status Intended Action August 3rd Incumbent List 1TV.COM, Inc. 1TV.Com, Inc. Accepted Upper C Band 2820 Communications, INC 2820 Communications INC Accepted Upper C Band 2B Productions, LLC 2B Productions, LLC Accepted Upper C Band 2G Media, Inc. 2G Media, Inc. Accepted Upper C Band 6 Johnson Road Licenses, Inc. 6 Johnson Road Licenses, Inc. Accepted Upper C Band A&A Communications (CBTS Technology Solutions) CBTS Technology Solutions Inc. Accepted Upper C Band A1A TV INC. A1A TV INC Accepted Upper C Band Absolute Communications II, L.L.C. Absolute Communications II, L.L.C. Accepted Upper C Band Academy of the Immaculate, Inc. Academy of the Immaculate, Inc. Accepted Upper C Band Acadia Broadcast Partners, Inc. ACADIA BROADCAST PARTNERS INC Accepted Upper C Band ACC Licensee, LLC ACC Licensee, LLC Accepted Upper C Band Access Cable Television, Inc. Access Cable Television, Inc. Accepted Upper C Band Across Nations ACROSS NATIONS Accepted Upper C Band ACTUALIDAD 990AM LICENSEE, LLC Actualidad 990AM Licensee, LLC Accepted Upper C Band ACTUALIDAD KEY LARGO LICENSEE, LLC Actualidad Key Largo FM Licensee, LLC Accepted Upper C Band ADAMS CATV INC Adams CATV Inc. Accepted Upper C Band Adams Radio of Delmarva Peninsula, LLC Adams Radio Of Delmarva Peninsula, LLC Accepted Upper C Band Adams Radio of Fort Wayne, LLC Adams Radio of Fort Wayne, LLC Accepted Upper C Band Adams Radio of Las Cruces, LLC ADAMS RADIO OF LAS CRUCES, LLC Accepted Upper C Band Adams Radio of Northern Indiana, LLC Adams Radio of Northern Indiana, LLC Accepted Upper C Band Adams Radio of Tallahassee, LLC Adams Radio of Tallahassee, LLC Accepted Upper C Band Advance Ministries, Inc. -

1 the Impact of the FCC's TV Duopoly Rule Relaxation on Minority And

The Impact of the FCC’s TV Duopoly Rule Relaxation on Minority and Women Owned Broadcast Stations 1999-2006 By: Prof. Allen S. Hammond, IV, Santa Clara University School of Law, Founding Director, BroadBand Institute of California (BBIC) With: Prof. Barbara O’Connor, California State University, Sacramento And Prof. Tracy Westin, University of Colorado Consultants: Prof. Alexander Field, Santa Clara University And Assoc. Prof. Catherine Sandoval, Santa Clara University School of Law, Co-Director, BBIC 1 The Impact of the FCC’s TV Duopoly Rule Relaxation on Minority and Women Owned Broadcast Stations 1999-20061 Executive Summary This study was commissioned to ascertain the impact of the Television Duopoly Rule (TVDR) on minority and female ownership of television broadcast stations. Currently, the only FCC rule deemed to be favorable to minority and female broadcast ownership is the Failed Station Solicitation Rule (FSSR) of the TVDR. The TVDR originally prohibited the ownership of more than one television broadcast station in a market. In 1996, due to industry efforts to protect market gains realized through the use of local management agreements (LMAs)2, the TVDR was amended to allow the ownership of two stations in certain markets provided only one of the two was a VHF station and the overlapping signals of the two owned stations originated from separate albeit contiguous markets. In addition, the acquired station was required to be economically “failing” or “failed” or unbuilt. In an effort to afford market access to potential minority and female owners, the FCC required the owners of the station to be acquired to provide public notice of its availability for acquisition. -

Staff Report

Staff Report To: Economic Development Commission Members From: Krista Linke, Director Date: October 6, 2017 Re: Case EDC 2017-09 – Sunbeam Development Case EDC 2017-09 – Sunbeam Development: A request for a 10-year tax abatement on $18,000,000 in real property investment for the construction of a 600,000 square foot modern bulk building facility expandable up to 1,000,000 square feet. Location: Franklin Tech Park – 500 Bartram Parkway Summary: 1. Characteristics of this location: Franklin Tech Park: 43.6172 acres and 18.93 acres, 62.5472 total. 2. Characteristics of this petitioner: Sunbeam Development Corporation and affiliate companies own and manage a diverse portfolio of real estate primarily located in Indiana and Florida. Developments include suburban office parks, light industrial parks and shopping centers. Sunbeam typically buys large tracts of land in growth areas and provides the funding and expertise for the infrastructure to support a major development. Sunbeam began investing in Indianapolis real estate in 1967 and has expanded into several multi- million dollar developments including quality office, retail and industrial properties. Our most visible holdings in Indianapolis include the 1,000 acre Exit Five Development in Fishers which has absorbed over 1.5 million square feet of office and industrial space since its inception in 1988, six shopping centers in Castleton that feature such anchor tenants as Weekends Only, Joann Etc., Gander Mountain and Costco, and the new 685 acre development, I-70 West Commerce Park, which is already home to more than 2 million square feet of modern bulk distribution business including Chewy.com. -

The 2015 Silver Circle Awards Will Honor Six Distinguished People

MARCH 2015 CHAPTER NEWS THE 2015 SILVER CIRCLE AWARDS WILL HONOR SIX DISTINGUISHED PEOPLE Mark A. Baker Teri Forbush Emilio Marrero The Board of Governors of the Suncoast Chapter of The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences voted to bestow the 2015 Silver Circle Awards to Mark Baker, Teri Forbush, Emilio Marrero, Jackie Nespral, César Núñez and Francisco “Cisco” Suarez. This is the 27th consecutive year that these awards have been given in South Florida. Mark Baker was hired in 1979 by WPBT Channel 2 in Miami as a studio cameraman for the production of two landmark programs on public television: ¿Que Pasa, USA?, television’s first bilingual sitcom, and Nightly Business Report, America’s first business news program. Since then, Mark has written, produced and directed numerous cultural, historical, arts and science programs for PBS including New Florida, The Flying Days of Riddle Field, Anatomy of a Hurricane, Miami: Reflections on the River, The Story of Florida’s State Parks and Wild Florida to name a few. Mark’s programs have earned many awards of distinction for WPBT. Teri Forbush was hired at WPBF in 1988 as a Director. With the exception of 6 years when she was a full-time producer, she continued to direct live newscasts at WPBF since signing on January 1, 1989. Currently, she is responsible for producing commercial and sales presentations, as well as editing these projects on Avid. Emilio Marrero did internships at WTVJ and WCIX in 1987. In 1988, he was hired by WSCV. Emilio is currently the Director of News Services for Baptist Health South Florida.