Rattlesnake Fern Botrychium Virginianum Plant Stalk for Spore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 5 Chapter 1 Introduction I. LIFE CYCLES and DIVERSITY of VASCULAR PLANTS the Subjects of This Thesis Are the Pteri

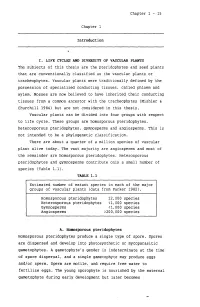

Chapter 1-15 Chapter 1 Introduction I. LIFE CYCLES AND DIVERSITY OF VASCULAR PLANTS The subjects of this thesis are the pteridophytes and seed plants that are conventionally classified as the vascular plants or tracheophytes. Vascular plants were traditionally defined by the possession of specialized conducting tissues, called phloem and xylem. Mosses are now believed to have inherited their conducting tissues from a common ancestor with the tracheophytes (Mishler & Churchill 1984) but are not considered in this thesis. Vascular plants can be divided into four groups with respect to life cycle. These groups are homosporous pteridophytes, heterosporous pteridophytes, gymnosperms and angiosperms. This is not intended to be a phylogenetic classification. There are about a quarter of a million species of vascular plant alive today. The vast majority are angiosperms and most of the remainder are homosporous pteridophytes. Heterosporous pteridophytes and gymnosperms contribute only a small number of species (Table 1.1). TABLE 1.1 Estimated number of extant species in each of the major groups of vascular plants (data from Parker 1982). Homosporous pteridophytes 12,000 species Heterosporous pteridophytes <1,000 species Gymnosperms <1,000 species Angiosperms >200,000 species A. Homosporous pteridophytes Homosporous pteridophytes produce a single type of spore. Spores are dispersed and develop into photosynthetic or mycoparasitic gametophytes. A gametophyte's gender is indeterminate at the time of spore dispersal, and a single gametophyte may produce eggs and/or sperm. Sperm are motile, and require free water to fertilize eggs. The young sporophyte is nourished by the maternal gametophyte during early development but later becomes Chapter 1-16 nutritionally independent. -

Reproduction in Plants Which But, She Has Never Seen the Seeds We Shall Learn in This Chapter

Reproduction in 12 Plants o produce its kind is a reproduction, new plants are obtained characteristic of all living from seeds. Torganisms. You have already learnt this in Class VI. The production of new individuals from their parents is known as reproduction. But, how do Paheli thought that new plants reproduce? There are different plants always grow from seeds. modes of reproduction in plants which But, she has never seen the seeds we shall learn in this chapter. of sugarcane, potato and rose. She wants to know how these plants 12.1 MODES OF REPRODUCTION reproduce. In Class VI you learnt about different parts of a flowering plant. Try to list the various parts of a plant and write the Asexual reproduction functions of each. Most plants have In asexual reproduction new plants are roots, stems and leaves. These are called obtained without production of seeds. the vegetative parts of a plant. After a certain period of growth, most plants Vegetative propagation bear flowers. You may have seen the It is a type of asexual reproduction in mango trees flowering in spring. It is which new plants are produced from these flowers that give rise to juicy roots, stems, leaves and buds. Since mango fruit we enjoy in summer. We eat reproduction is through the vegetative the fruits and usually discard the seeds. parts of the plant, it is known as Seeds germinate and form new plants. vegetative propagation. So, what is the function of flowers in plants? Flowers perform the function of Activity 12.1 reproduction in plants. Flowers are the Cut a branch of rose or champa with a reproductive parts. -

Vascular Plants (About 425 Mya)

LECTURE PRESENTATIONS For CAMPBELL BIOLOGY, NINTH EDITION Jane B. Reece, Lisa A. Urry, Michael L. Cain, Steven A. Wasserman, Peter V. Minorsky, Robert B. Jackson Chapter 29 Plant Diversity I: How Plants Colonized Land Lectures by Erin Barley Kathleen Fitzpatrick © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc. Overview: The Greening of Earth • For more than the first 3 billion years of Earth’s history, the terrestrial surface was lifeless • Cyanobacteria likely existed on land 1.2 billion years ago • Around 500 million years ago, small plants, fungi, and animals emerged on land © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc. • Since colonizing land, plants have diversified into roughly 290,000 living species • Land plants are defined as having terrestrial ancestors, even though some are now aquatic • Land plants do not include photosynthetic protists (algae) • Plants supply oxygen and are the ultimate source of most food eaten by land animals © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc. Figure 29.1 1 m Concept 29.1: Land plants evolved from green algae • Green algae called charophytes are the closest relatives of land plants © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc. Morphological and Molecular Evidence • Many characteristics of land plants also appear in a variety of algal clades, mainly algae • However, land plants share four key traits with only charophytes – Rings of cellulose-synthesizing complexes – Peroxisome enzymes – Structure of flagellated sperm – Formation of a phragmoplast © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc. Figure 29.2 30 nm 1 m • Comparisons of both nuclear and chloroplast genes point to charophytes as the closest living relatives of land plants • Note that land plants are not descended from modern charophytes, but share a common ancestor with modern charophytes © 2011 Pearson Education, Inc. -

Heterospory: the Most Iterative Key Innovation in the Evolutionary History of the Plant Kingdom

Biol. Rej\ (1994). 69, l>p. 345-417 345 Printeii in GrenI Britain HETEROSPORY: THE MOST ITERATIVE KEY INNOVATION IN THE EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY OF THE PLANT KINGDOM BY RICHARD M. BATEMAN' AND WILLIAM A. DiMlCHELE' ' Departments of Earth and Plant Sciences, Oxford University, Parks Road, Oxford OXi 3P/?, U.K. {Present addresses: Royal Botanic Garden Edinburiih, Inverleith Rojv, Edinburgh, EIIT, SLR ; Department of Geology, Royal Museum of Scotland, Chambers Street, Edinburgh EHi ijfF) '" Department of Paleohiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC^zo^bo, U.S.A. CONTENTS I. Introduction: the nature of hf^terospon' ......... 345 U. Generalized life history of a homosporous polysporangiophyle: the basis for evolutionary excursions into hetcrospory ............ 348 III, Detection of hcterospory in fossils. .......... 352 (1) The need to extrapolate from sporophyte to gametophyte ..... 352 (2) Spatial criteria and the physiological control of heterospory ..... 351; IV. Iterative evolution of heterospory ........... ^dj V. Inter-cladc comparison of levels of heterospory 374 (1) Zosterophyllopsida 374 (2) Lycopsida 374 (3) Sphenopsida . 377 (4) PtiTopsida 378 (5) f^rogymnospermopsida ............ 380 (6) Gymnospermopsida (including Angiospermales) . 384 (7) Summary: patterns of character acquisition ....... 386 VI. Physiological control of hetcrosporic phenomena ........ 390 VII. How the sporophyte progressively gained control over the gametophyte: a 'just-so' story 391 (1) Introduction: evolutionary antagonism between sporophyte and gametophyte 391 (2) Homosporous systems ............ 394 (3) Heterosporous systems ............ 39(1 (4) Total sporophytic control: seed habit 401 VIII. Summary .... ... 404 IX. .•Acknowledgements 407 X. References 407 I. I.NIRODUCTION: THE NATURE OF HETEROSPORY 'Heterospory' sensu lato has long been one of the most popular re\ie\v topics in organismal botany. -

Laboratory 8: Ginkgo, Cycads, and Gnetophytes

IB 168 – Plant Systematics Laboratory 8: Ginkgo, Cycads, and Gnetophytes This is the third and final lab concerning the gymnosperms. Today we are looking at Ginkgo, the Cycads, and the Gnetophytes, the so-called non-coniferous gymnosperms. While these groups do not have cones like the true conifers, many do produce strobili. Order Ginkgoales: leaves simple (with dichotomously branching venation); dimorphic shoots; water-conducting cells are tracheids; dioecious; generally two ovules produced on an axillary stalk or "peduncle"; microsporangiate strobili loose and catkin-like; multi-flagellate sperm. Ginkgoaceae – 1 genus, 1 sp., cultivated relict native to China Tree, tall, stately with curving branches attached to a short trunk. Leaves fan shaped, deciduous, attached in whorls to the end of "short shoots" growing from the longer branches ("long shoots"); veins of the leaves dichotomously branched; dioecious; paired ovules at the end of a stalk and naked, hanging like cherries; seeds enclosed in a fleshy whitish-pink covering. Ginkgo Order Cycadales: pinnately-compound leaves, whorled, attached spirally at the stem apex; main stem generally unbranched; circinate vernation in some representatives; water-conducting cells are tracheids; dioecious; both male and female cones are simple structures; seeds generally large and round, unwinged; numerous microsporangia per microsporophyll; multi-flagellate sperm. Cycadaceae – 1 genus, 17 spp., Africa, Japan, and Australia Stems palm-like and rough, usually not branched; leaves fern-like, pinnately compound, thick and leathery; attached spirally at the stem apex, young pinnae with circinate vernation, leaf bases remaining after the leaves drop; dioecious; whorls of wooly-covered micro- and megasporophylls alternate with whorls of scales and foliage leaves at the stem apex; ovules born along the sporophyll margins; seed almond or plum like; ovules borne along the margin of the leaf- like megasporophyll. -

Spore Reproduction of Japanese Climbing Fern in Florida As a Function of Management Timing

Spore Reproduction of Japanese Climbing Fern in Florida as a Function of Management Timing Candice M. Prince1, Dr. Gregory E. MacDonald1, Dr. Kimberly Bohn2, Ashlynn Smith1, and Dr. Mack Thetford1 1University of Florida, 2Pennsylvania State University Photo Credit: Chris Evans, University of Illinois, Bugwood.org Exotic climbing ferns in Florida Old world climbing fern Japanese climbing fern (Lygodium microphyllum) (Lygodium japonicum) Keith Bradley, Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants Chris Evans, University of Illinois, Bugwood.org Japanese climbing fern (Lygodium japonicum) • Native to temperate and tropical Asia • Climbing habit • Early 1900s: introduced as an ornamental1 • Long-distance dispersal via wind, pine straw bales2,3 Chris Evans, University of Illinois, Bugwood.org Dennis Teague, U.S. Air Force, Bugwood.org Distribution • Established in 9 southeastern states • In FL: present throughout the state, USDA NRCS National Plant Data Team, 2016 but most invasive in northern areas • Winter dieback, re-sprouts from rhizomes1 • Occurs in mesic and temporally hydric areas1 Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants, Institute of Systemic Botany, 2016 Impacts Chris Evans, University of Illinois, Bugwood.org • Smothers and displaces vegetation, fire ladders • Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council: Category I species Chuck Bargeron, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org • Florida Noxious Weed List • Alabama Noxious Weed List (Class B) Japanese climbing fern: life cycle John Tiftickjian, Sigel Lab, University of Delta State University Louisiana at Lafayette -

Educator Guide

Educator Guide Presented by The Field Museum Education Department INSIDE: s )NTRODUCTION TO "OTANY s 0LANT $IVISIONS AND 2ELATED 2ESEARCH s #URRICULUM #ONNECTIONS s &OCUSED &IELD 4RIP !CTIVITIES s +EY 4ERMS Introduction to Botany Botany is the scientific study of plants and fungi. Botanists (plant scientists) in The Field Museum’s Science and Education Department are interested in learning why there are so many different plants and fungi in the world, how this diversity is distributed across the globe, how best to classify it, and what important roles these organisms play in the environment and in human cultures. The Field Museum acquired its first botanical collections from the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 when Charles F. Millspaugh, a physician and avid botanist, began soliciting donations of exhibited collections for the Museum. In 1894, the Museum’s herbarium was established with Millspaugh as the Museum’s first Curator of Botany. He helped to expand the herbarium to 50,000 specimens by 1898, and his early work set the stage for the Museum’s long history of botanical exploration. Today, over 70 major botanical expeditions have established The Field’s herbarium as one of the world’s preeminent repositories of plants and fungi with more than 2.7 million specimens. These collections are used to study biodiversity, evolution, conservation, and ecology, and also serves as a depository for important specimens and material used for drug screening. While flowering plants have been a major focus during much of the department’s history, more recently several staff have distinguished themselves in the areas of economic botany, evolutionary biology and mycology. -

Plant Propagation Lab Exercise Module 2

Plant Propagation Lab Exercise Module 2 PROPAGATION OF SPORE BEARING PLANTS FERNS An introduction to plant propagation laboratory exercises by: Gabriel Campbell-Martinez and Dr. Mack Thetford Plant Propagation Lab Exercise Module 2 PROPAGATION OF SPORE BEARING PLANTS FERNS An introduction to plant propagation laboratory exercises by: Gabriel Campbell-Martinez and Dr. Mack Thetford LAB OBJECTIVES • Introduce students to the life cycle of ferns. • Demonstrate the appropriate use of terms to describe the morphological characteristics for describing the stages of fern development. • Demonstrate techniques for collection, cleaning, and sowing of fern spores. • Provide alternative systems for fern spore germination in home or commercial settings. Fern spore germination Fern relationship to other vascular plants Ferns • Many are rhizomatous and have circinate vernation • Reproduce sexually by spores • Eusporangiate ferns • ~250 species of horsetails, whisk ferns moonworts • Leptosporangiate • ~10,250 species Sporophyte Generation Spores are produced on the mature leaves (fronds) of the sporophyte generation of ferns. The spores are arranged in sporangia which are often inside a structure called a sorus. The sori often have a protective covering of living leaf tissue over them that is called an indusium. As the spores begin to mature the indusium may also go through physical changes such as a change in color or desiccating and becoming smaller as it dries to allow an opening for dispersal. The spores (1n) may be wind dispersed or they may require rain (water) to aid in dispersal. Gametophyte Generation The gametophyte generation is initiated with the germination of the spore (1n). The germinated spore begins to grow and form a heart-shaped structure called a prothallus. -

Ancient Noeggerathialean Reveals the Seed Plant Sister Group Diversified Alongside the Primary Seed Plant Radiation

Ancient noeggerathialean reveals the seed plant sister group diversified alongside the primary seed plant radiation Jun Wanga,b,c,1, Jason Hiltond,e, Hermann W. Pfefferkornf, Shijun Wangg, Yi Zhangh, Jiri Beki, Josef Pšenickaˇ j, Leyla J. Seyfullahk, and David Dilcherl,m,1 aState Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China; bCenter for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China; cUniversity of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shijingshan District, Beijing 100049, China; dSchool of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; eBirmingham Institute of Forest Research, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; fDepartment of Earth and Environmental Science, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6316; gState Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xiangshan, Beijing 100093, China; hCollege of Paleontology, Shenyang Normal University, Key Laboratory for Evolution of Past Life in Northeast Asia, Ministry of Natural Resources, Shenyang 110034, China; iDepartment of Palaeobiology and Palaeoecology, Institute of Geology v.v.i., Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, 165 00 Praha 6, Czech Republic; jCentre of Palaeobiodiversity, West Bohemian Museum in Plzen, 301 36 Plzen, Czech Republic; kDepartment of Paleontology, Geozentrum, University of Vienna, 1090 Vienna, Austria; lIndiana Geological and Water Survey, Bloomington, IN 47404; and mDepartment of Geology and Atmospheric Science, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405 Contributed by David Dilcher, September 10, 2020 (sent for review July 2, 2020; reviewed by Melanie Devore and Gregory J. -

Phlorotannins from Undaria Pinnatifida Sporophyll: Extraction, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities

Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering Publications Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering 7-24-2019 Phlorotannins from Undaria pinnatifida Sporophyll: Extraction, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities Xiufang Dong Dalian Polytechnic University Ying Bai Dalian Polytechnic University Zhe Xu Dalian Polytechnic University Yixin Shi Dalian Polytechnic University Yihan Sun Dalian Polytechnic University See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/abe_eng_pubs Part of the Amino Acids, Peptides, and Proteins Commons, Bioresource and Agricultural Engineering Commons, and the Marine Biology Commons The complete bibliographic information for this item can be found at https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ abe_eng_pubs/1147. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Phlorotannins from Undaria pinnatifida Sporophyll: Extraction, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities Abstract Undaria pinnatifida sporophyll (U. pinnatifida) is a major byproduct of U. pinnatifida (a brown algae) processing. Its phenolic constituents, phlorotannins, are of special interest due to their -

Histochemistry of Spore Mucilage and Inhibition of Spore Adhesion in Champia Parvula, a Marine Alga

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 1994 Histochemistry of Spore Mucilage and Inhibition of Spore Adhesion in Champia parvula, A Marine Alga Martha E. Apple University of Rhode Island Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Apple, Martha E., "Histochemistry of Spore Mucilage and Inhibition of Spore Adhesion in Champia parvula, A Marine Alga" (1994). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 783. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/783 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HISTOCHEMISTRY OF SPORE MUCILAGE AND INHIBITION OF SPORE ADHESION IN CHAMPIA PARVULA, A MARINE RED ALGA. BY MARTHA E. APPLE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 1994 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF MARTHA E. APPLE APPROVED: Dissertation Committee Major Professor DEAN OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 1994 Abstract Spores of the marine red alga, Champja parvu!a, attached initially to plastic or glass cover slips by extracellular mucilage. Adhesive rhizoids emerged from germinating spores, provided a further basis of attachment and rhizoidal division formed the holdfast. Mucilage of holdfasts and attached spores stained for sulfated and carboxylated polysaccharides. Rhizoids and holdfast cells but not mucilage stained for protein. Removal of holdfasts with HCI revealed protein anchors in holdfast cell remnants. Spores detached when incubated in the following enzymes: 13-galactosidase, protease, ce!!u!ase, a-amylase, hya!uronidase, sulfatase, and mannosidase. -

Structure and Function of Spores in the Aquatic Heterosporous Fern Family Marsileaceae

Int. J. Plant Sci. 163(4):485–505. 2002. ᭧ 2002 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 1058-5893/2002/16304-0001$15.00 STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF SPORES IN THE AQUATIC HETEROSPOROUS FERN FAMILY MARSILEACEAE Harald Schneider1 and Kathleen M. Pryer2 Department of Botany, Field Museum of Natural History, 1400 South Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, Illinois 60605-2496, U.S.A. Spores of the aquatic heterosporous fern family Marsileaceae differ markedly from spores of Salviniaceae, the only other family of heterosporous ferns and sister group to Marsileaceae, and from spores of all ho- mosporous ferns. The marsileaceous outer spore wall (perine) is modified above the aperture into a structure, the acrolamella, and the perine and acrolamella are further modified into a remarkable gelatinous layer that envelops the spore. Observations with light and scanning electron microscopy indicate that the three living marsileaceous fern genera (Marsilea, Pilularia, and Regnellidium) each have distinctive spores, particularly with regard to the perine and acrolamella. Several spore characters support a division of Marsilea into two groups. Spore character evolution is discussed in the context of developmental and possible functional aspects. The gelatinous perine layer acts as a flexible, floating organ that envelops the spores only for a short time and appears to be an adaptation of marsileaceous ferns to amphibious habitats. The gelatinous nature of the perine layer is likely the result of acidic polysaccharide components in the spore wall that have hydrogel (swelling and shrinking) properties. Megaspores floating at the water/air interface form a concave meniscus, at the center of which is the gelatinous acrolamella that encloses a “sperm lake.” This meniscus creates a vortex-like effect that serves as a trap for free-swimming sperm cells, propelling them into the sperm lake.