How Cable News Pundits Protect the Glass Ceiling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moments That Matter Executive Summary 2017 Corporate Social Responsibility Report (Covering 2016)

Moments that matter Executive Summary 2017 Corporate Social Responsibility Report (covering 2016) At Comcast NBCUniversal, we bring people closer to what matters. To the moments of purpose and passion that make our world a better place. About our commitment “Across all of our businesses “As a technology and broadband and platforms, we have a unique leader, it is our responsibility opportunity to connect people and obligation to do what to the moments that matter we can to help close the most to them.” digital divide.” BRIAN L. ROBERTS DAVID L. COHEN Chairman and CEO Senior Executive Vice President and Chief Diversity Officer From our place as one of the largest media, technology, and broadband companies in the world, we have the unique ability to help solve some of the most challenging social issues of our time. Our impact starts with our philanthropy and volunteerism, and it grows with our efforts to connect the unconnected and our ability to amplify the voices of today’s change- makers in our communities and within our own walls. That’s why we invest in digital inclusion, foster the brightest innovators and entrepreneurs, and spotlight young, diverse filmmakers. It’s why we hold up the microphone for community problem-solvers, and uphold and empower our own Comcast NBCUniversal family to make a lasting difference. Our influence and reach make it possible to create a positive impact every day. $500+ million In 2016, Comcast NBCUniversal provided more than $500 million in cash and in-kind contributions to local and national organizations that share our commitment to improving communities. -

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 100 PODCASTS by DOWNLOADS Podcasts Ranked by Average Weekly Downloads in the United States Reporting Period: March 16 - April 12, 2020

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 100 PODCASTS BY DOWNLOADS Podcasts Ranked by Average Weekly Downloads in the United States Reporting Period: March 16 - April 12, 2020 # OF NEW RANK PODCAST PODCAST NETWORK SALES REPRESENTATION EPISODES CHANGE 1 NPR News Now NPR National Public Media 672 0 2 Up First NPR National Public Media 30 h2 3 The Ben Shapiro Show Cumulus Media/Westwood One Cumulus Media/Westwood One 22 0 4 My Favorite Murder with Karen Kilgariff Stitcher Midroll 9 i2 and Georgia Hardstark 5 Planet Money NPR National Public Media 11 h3 6 NPR Politics NPR National Public Media 21 h1 7 Fresh Air NPR National Public Media 24 i1 8 Pod Save America RADIO.COM/Cadence13 Cadence 13 8 h1 9 Dateline NBC NBC News Wondery Brand Partnerships 13 i4 10 Indicator from Planet Money NPR National Public Media 20 h3 11 Hidden Brain NPR National Public Media 4 i1 12 Fox News Radio Newscast FOX News Podcasts FOX News Podcasts 672 h4 13 TED Radio Hour NPR National Public Media 5 h1 14 Office Ladies Stitcher Midroll 4 i3 15 How I Built This NPR National Public Media 6 0 16 Wait Wait... Don't Tell Me! NPR National Public Media 5 h5 17 The Dan Bongino Show Cumulus Media/Westwood One Cumulus Media/Westwood One 21 i5 18 Freakonomics Radio Stitcher Midroll 5 h1 19 The Rachel Maddow Show NBC News Wondery Brand Partnerships 21 h1 20 Unlocking Us with Brené Brown RADIO.COM/Cadence13 Cadence13 7 New 21 Conan O’Brien Needs A Friend Stitcher Midroll 4 i3 22 Oprah’s SuperSoul Conversations Stitcher Midroll 4 i5 23 VIEWS with David Dobrik and Jason RADIO.COM/Cadence13 Cadence13 -

The Misrepresented Road to Madame President: Media Coverage of Female Candidates for National Office

THE MISREPRESENTED ROAD TO MADAME PRESIDENT: MEDIA COVERAGE OF FEMALE CANDIDATES FOR NATIONAL OFFICE by Jessica Pinckney A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Government Baltimore, Maryland May, 2015 © 2015 Jessica Pinckney All Rights Reserved Abstract While women represent over fifty percent of the U.S. population, it is blatantly clear that they are not as equally represented in leadership positions in the government and in private institutions. Despite their representation throughout the nation, women only make up twenty percent of the House and Senate. That is far from a representative number and something that really hurts our society as a whole. While these inequalities exist, they are perpetuated by the world in which we live, where the media plays a heavy role in molding peoples’ opinions, both consciously and subconsciously. The way in which the media presents news about women is not always representative of the women themselves and influences public opinion a great deal, which can also affect women’s ability to rise to the top, thereby breaking the ultimate glass ceilings. This research looks at a number of cases in which female politicians ran for and/or were elected to political positions at the national level (President, Vice President, and Congress) and seeks to look at the progress, or lack thereof, in media’s portrayal of female candidates running for office. The overarching goal of the research is to simply show examples of biased and unbiased coverage and address the negative or positive ways in which that coverage influences the candidate. -

Representations and Discourse of Torture in Post 9/11 Television: an Ideological Critique of 24 and Battlestar Galactica

REPRESENTATIONS AND DISCOURSE OF TORTURE IN POST 9/11 TELEVISION: AN IDEOLOGICAL CRITIQUE OF 24 AND BATTLSTAR GALACTICA Michael J. Lewis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2008 Committee: Jeffrey Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin ii ABSTRACT Jeffrey Brown Advisor Through their representations of torture, 24 and Battlestar Galactica build on a wider political discourse. Although 24 began production on its first season several months before the terrorist attacks, the show has become a contested space where opinions about the war on terror and related political and military adventures are played out. The producers of Battlestar Galactica similarly use the space of television to raise questions and problematize issues of war. Together, these two television shows reference a long history of discussion of what role torture should play not just in times of war but also in a liberal democracy. This project seeks to understand the multiple ways that ideological discourses have played themselves out through representations of torture in these television programs. This project begins with a critique of the popular discourse of torture as it portrayed in the popular news media. Using an ideological critique and theories of televisual realism, I argue that complex representations of torture work to both challenge and reify dominant and hegemonic ideas about what torture is and what it does. This project also leverages post-structural analysis and critical gender theory as a way of understanding exactly what ideological messages the programs’ producers are trying to articulate. -

A NATIONAL CONFERENCE Define Justice

RY SA VER ANNI C’S 30th AR FACING RACE A NATIONAL CONFERENCE Define Justice. Make Change. November 15-17, 2012 BALTIMORE HILTON BALTIMORE, MD 30/.3/2%$ "9 4(% !00,)%$ 2%3%!2#( #%.4%2 s !2#/2' THE APPLIED RESEARCH CENTER’S (ARC) MISSION IS TO BUILD AWARENESS, SOLUTIONS, AND LEADERSHIP FOR RACIAL JUSTICE BY GENERATING TRANSFORMATIVE IDEAS, INFORMATION AND EXPERIENCES. ABOUT ARC The Applied Research Center (ARC) is a thirty-year-old, national racial justice organization. ARC envisions a vibrant world in which people of all races create, share and enjoy resources and relationships equitably, unleashing individual potential, embracing collective responsibility and generating global prosperity. We strive to be a leading values-driven social justice enterprise where the culture and commitment created by our multi-racial and diverse staff supports individual and organizational excellence and sustainability. ARC’s mission is to build awareness, solutions and leadership for racial justice by generating transformative ideas, information and experiences. We define racial justice as the systematic fair treatment of people of all races, resulting in equal opportunities and outcomes for all and we work to advance racial justice through media, research, and leadership development. s MEDIA: ARC is the publisher of Colorlines.com, an award-winning, daily news site where race matters. Colorlines brings a critical racial lens and analysis to breaking news stories, as well as in-depth investigations. In 2012, Colorlines’ Shattered Families investigation was awarded the Hillman Prize in Web Journalism and Colorlines partnered with The Nation on the Voting Rights Watch series. In addition to promoting racial justice through our own media, ARC staff is sought after as experts on current race issues, with regular media appearances on MSNBC, NPR, and other national and local broadcast, print, and online outlets. -

August Sunday Talk Shows Data

August Sunday Talk Shows Data August 1, 2010 21 men and 6 women NBC's Meet the Press with David Gregory: 5 men and 1 woman Admiral Michael Mullen (M) Mayor Michael Bloomberg (M) Alan Greenspan (M) Gov. Ed Rendell (M) Doris Kearns Goodwin (F) Mark Halperin (M) CBS's Face the Nation with Bob Schieffer: 4 men and 0 women Admiral Michael Mullen (M) Sen. Jon Kyl (M) Richard Haass (M) Thomas Saenz (M) ABC's This Week with Jake Tapper: 4 men and 2 women Sen. Nancy Pelosi (F) Robert Gates (M) George Will (M) Paul Krugman (M) Donna Brazile (F) Ahmed Rashid (M) CNN's State of the Union with Candy Crowley: 4 men and 0 women Sen. Carl Levin (M) Sen. Lindsey Graham (M) Dan Balz (M) Peter Baker (M) Fox News' Fox News Sunday with Chris Wallace: 4 men and 3 women Sarah Palin (F) Sen. Mitch McConnell (M) Rep. John Boehner (M) Bill Kristol (M) Ceci Connolly (F) Liz Cheney (F) Juan Williams (M) August 8, 2010 20 men and 7 women NBC's Meet the Press with David Gregory: 4 men and 2 women Carol Browner (F) Rep. John Boehner (M) Rep. Mike Pence (M) former Rep. Harold Ford (M) Andrea Mitchell (F) Todd S. Purdum (M) CBS's Face the Nation with Bob Schieffer: 4 men and 1 woman Admiral Thad Allen (M) David Boies (M) Tony Perkins (M) Dan Balz (M) Jan Crawford (F) ABC's This Week with Jake Tapper: 5 men and 1 woman General Ray Odierno (M) Gen. -

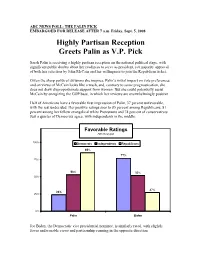

Highly Partisan Reception Greets Palin As V.P. Pick

ABC NEWS POLL: THE PALIN PICK EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE AFTER 7 a.m. Friday, Sept. 5, 2008 Highly Partisan Reception Greets Palin as V.P. Pick Sarah Palin is receiving a highly partisan reception on the national political stage, with significant public doubts about her readiness to serve as president, yet majority approval of both her selection by John McCain and her willingness to join the Republican ticket. Given the sharp political divisions she inspires, Palin’s initial impact on vote preferences and on views of McCain looks like a wash, and, contrary to some prognostication, she does not draw disproportionate support from women. But she could potentially assist McCain by energizing the GOP base, in which her reviews are overwhelmingly positive. Half of Americans have a favorable first impression of Palin, 37 percent unfavorable, with the rest undecided. Her positive ratings soar to 85 percent among Republicans, 81 percent among her fellow evangelical white Protestants and 74 percent of conservatives. Just a quarter of Democrats agree, with independents in the middle. Favorable Ratings ABC News poll 100% Democrats Independents Republicans 85% 77% 75% 53% 52% 50% 27% 24% 25% 0% Palin Biden Joe Biden, the Democratic vice presidential nominee, is similarly rated, with slightly fewer unfavorable views and partisanship running in the opposite direction. Palin: Biden: Favorable Unfavorable Favorable Unfavorable All 50% 37 54% 30 Democrats 24 63 77 9 Independents 53 34 52 31 Republicans 85 7 27 60 Men 54 37 55 35 Women 47 36 54 27 IMPACT – The public by a narrow 6-point margin, 25 percent to 19 percent, says Palin’s selection makes them more likely to support McCain, less than the 12-point positive impact of Biden on the Democratic ticket (22 percent more likely to support Barack Obama, 10 percent less so). -

The Usage of Partisan News and Its Impact on Compromise by Laura

The Usage of Partisan News and Its Impact on Compromise by Laura Evans B.A. in Political Science & Law and Society, Dec 1999, American University M.A. in Applied Politics, Dec 2000, American University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 18, 2014 Dissertation directed by John Sides Associate Professor of Political Science The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Laura Evans has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of March 24, 2014. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. The Usage of Partisan News and Its Impact on Compromise Laura Evans Dissertation Research Committee: John Sides, Associate Professor of Political Science, Dissertation Director Kimberly Gross, Associate Professor of Media and Public Affairs, Committee Member Eric Lawrence, Associate Professor of Political Science, Committee Member ii Abstract of Dissertation The Usage of Partisan News and Its Impact on Compromise In the last few years news media has undergone massive fragmentation, calling into question the existence and sustainability of mass media. This trend is compounded by a rise in politically slanted news alternatives. This work will seek to uncover what impact this new media environment, particularly the ability it has given people to selectively choose their news consumption, has on cross-cutting political exposure, ideology and willingness to compromise. I argue that the ability to selectively choose which news outlets and what articles a person will read will cause ideologues to choose those that seem to fit their political point of view. -

Handbook of Sports and Media

Job #: 106671 Author Name: Raney Title of Book: Handbook of Sports & Media ISBN #: 9780805851892 HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA LEA’S COMMUNICATION SERIES Jennings Bryant/Dolf Zillmann, General Editors Selected titles in Communication Theory and Methodology subseries (Jennings Bryant, series advisor) include: Berger • Planning Strategic Interaction: Attaining Goals Through Communicative Action Dennis/Wartella • American Communication Research: The Remembered History Greene • Message Production: Advances in Communication Theory Hayes • Statistical Methods for Communication Science Heath/Bryant • Human Communication Theory and Research: Concepts, Contexts, and Challenges, Second Edition Riffe/Lacy/Fico • Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research, Second Edition Salwen/Stacks • An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA Edited by Arthur A.Raney College of Communication Florida State University Jennings Bryant College of Communication & Information Sciences The University of Alabama LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS Senior Acquisitions Editor: Linda Bathgate Assistant Editor: Karin Wittig Bates Cover Design: Tomai Maridou Photo Credit: Mike Conway © 2006 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2009. To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk. Copyright © 2006 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook of sports and media/edited by Arthur A.Raney, Jennings Bryant. p. cm.–(LEA’s communication series) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

This Is What Occupy Wall Street Looks Like!

Published on Coffee Party (http://www.coffeepartyusa.com) Home > Blogs > Coffee Party Nation's blog > Printer-friendly PDF What does Occupy Wall Street look like? This is what Occupy Wall Street looks like! Mon, 10/24/2011 - 8:24pm — Coffee Party Nation Occupy Wall Street[1] by John Park On October 5th, when the Steering Committee of Korean Americans for Political Advancement (KAPA), which includes two Coffee Party members, joined the 20,000+ people supporting the Occupy Wall Street (OWS) march, a KAPA member was interviewed by a New York Times reporter and later had her photograph uploaded online under the title: ?What to Wear to a Protest?? This does not reflect what Occupy Wall Street looks like, but it does reflect the problem of why people don?t know. Beholden to revenue-generating forces, even well-respected news establishments aren?t above commercializing resistance or viewing current events through green-tinted lenses. With banks annoying people into becoming their customers with a deluge of well-funded advertisements about what is ?priceless? or ?what?s in your wallet,? and media outlets unafraid of losing their financial support from OWS because, frankly, there isn?t any, it?s easy to see why most people aren?t getting a fair portrayal of who the Occupiers and supporters really are. And the banks aren?t just purchasing the influence of politicians?they are purchasing influence among law enforcement. Large donations were made to NYPD, including the recent donation from J.P. Morgan of $4.6 million, have no doubt exacerbated the already aggressive posture of NYPD towards the protesters. -

Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election

Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Faris, Robert M., Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUGUST 2017 PARTISANSHIP, Robert Faris Hal Roberts PROPAGANDA, & Bruce Etling Nikki Bourassa DISINFORMATION Ethan Zuckerman Yochai Benkler Online Media & the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is the result of months of effort and has only come to be as a result of the generous input of many people from the Berkman Klein Center and beyond. Jonas Kaiser and Paola Villarreal expanded our thinking around methods and interpretation. Brendan Roach provided excellent research assistance. Rebekah Heacock Jones helped get this research off the ground, and Justin Clark helped bring it home. We are grateful to Gretchen Weber, David Talbot, and Daniel Dennis Jones for their assistance in the production and publication of this study. This paper has also benefited from contributions of many outside the Berkman Klein community. The entire Media Cloud team at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab has been essential to this research. -

Baker, James A.: Files Folder Title: Political Affairs January 1984-July 1984 (3) Box: 9

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Baker, James A.: Files Folder Title: Political Affairs January 1984-July 1984 (3) Box: 9 To see more digitized collections visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digital-library To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://reaganlibrary.gov/document-collection Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/citing National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ REAGAN-00SH'84 The President's Authorized Campaign Committee M E M 0 R A N D U M TO: Jim Baker, Mike Deaver, Dick Darman, Margaret Tutwiler, Mike McManus THROUGH: Ed Rollins FROM: Doug Watts DATE: June 6, 1984 RE: Television Advertising Recently, the idea was advanced that Reagan-Bush '84 should develop negative television advertising - utilizing derisive issue and personality oriented statements made by Democratic presidential candidates about one another - to be broadcast during the periods ten days before and after the Democratic Convention {July 16-20). The thought apparently was to highlight within an issue framework, not only the chaotic and contentious democratic contest, but to point out the insipid, petty and self-serving manner in which the debate has been conducted. The attack themes presumably were to be directed primarily at Mondale and Hart before the convention and at the nominee following the convention. The above described approach was discussed Thursday and Friday {5/31/84 & 6/1/84) during a meeting with myself, Ed Rollins, Lee Atwater and Jim Lake, and then myself and the Tuesday Team.