The Last Angel of History Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Among Us by Nina Runa Essendrop

1 . Among us By Nina Runa Essendrop A poetic and sensuous scenario about human loneliness and about the longing of the angels for the profound beauty which is found in every human life. 2 Preview Humans are ever present. They see the world in colors. They feel and they think and they walk on two feet. They touch the water and feel the cold softness of the surface. They gaze at the horizon and think deep thoughts about their existence. Humans feel the wind against their faces, they laugh and they cry and their pleading eyes seek for a meaning in the world around them. They breathe too fast and they forget to feel the ground under their feet or the invisible hand on their shoulder, which gently offers them comfort and peace. Angels exist among the humans. Invisible and untouchable they witness how humans live their lives. Their silent voices gently form mankind’s horizons, far away and so very very close that only children and dreamers will sense their presence. "Among us" is a poetic and sensuous scenario about a lonely human being, an angel who chooses the immediacy of mortal life, and an angel who continues to be the invisible guardian of mankind. It is a slow and thoughtful experience focussing on how beautiful, difficult and meaningful it is to be a human being. The scenario is played as a chamber larp and the players will be prepared for the play-style and tools through a workshop. The scenario is based on the film ”Wings of Desire” by Win Wender. -

The Second Try

The Second Try Jimmy Wolk Chapter I: The 12th Shinji Ikari, Third Children and designated pilot of Evangelion Unit-01, had just reached a new sync- ratio record. And as Rei Ayanami suspected, the former holder of this record, known as Asuka Langley Soryu, wasn't very pleased with this. So she didn't pay much attention to the rants of the Second Children, who made obviously ironical statements about the 'great, invincible Shinji' while holding herself; swaying in front of her locker. Instead, Rei finished changing from the plugsuit the pilots were supposed to wear during their time in the entry plugs of the EVAs or the test plugs, into her casual school uniform. As soon as she was done, she went silently for the door of the female pilots' changing room, whispered "Sayonara" and left. With the First Children gone, Asuka could finally release all the feelings that tensed up the last hours in a powerful... ...sigh. She still had problems to play this charade in front of everyone, and it seemed to only grow harder. She wasn't sure if she would be able to keep it up much longer at all. Not while these thoughts disturbed her mind; thoughts of all the things that happened... or will happen soon. Lost in her worries, she failed to notice someone entering the room, sneaking up to her and suddenly embracing her from behind; encircling her arms with his own. She tensed up noticeably as she felt the touch, even though (or maybe just because) she knew exactly who the stranger was. -

The Sunday Book of Poetry

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fe Wi ilkWMWM niiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii no THE GIFT OF Prof .Aubrey Tealdi iiiiuiiiiiiiiiiuiiiiiiiiiiiiMiiiiiuiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiuiHiiiiiiiiiiuiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii.il!!: tJU* A37f , k LONDON : R. CLAY, SON, AND TAYLOR, PRINTERS, BREAD STREET HILL. Fourth Thousand. THE SUNDAY BOOK OF POETRY SELECTED AND ARRANGED BY V,v ., .O" F^-A*! EX A N D E R AUTHOR OF "HYMNS FOR LITTLE CHILDREN," ETC. Jfambou srab Cambridge : MACMILLAN AND CO. 1865. A Taip in&e' when tonat v.... <lu: lie Ria sev ate Pi di . B IT- PREFACE The present volume will, it is hoped, be found to contain a selection of Sacred Poetry, of such a character as can be placed with profit and pleasure in the hands of intelligent children from eight to fourteen years of age, both on Sundays and at other times. It may be well for the Compiler to make some remarks upon the principles which have been adopted in the present selection. Dr. Johnson has said that " the word Sacred should never be applied but where some reference may be made to a higher Being, or where some duty is exacted, or implied." The Compiler be lieves she has selected few poems whose insertion may not be justified by this definition, though several perhaps may not be of such a nature as are popularly termed sacred. Those which appear under the division of the Incarnate Word, and of Praise, and Prayer, are of course in some cases directly hymns, and in all cases founded upon the great doctrines of the Christian faith, or upon the events of the Redeemer's life. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

Native Instruments Releases the Second Installment in the EVERYBODY DJ Video Series

Native Instruments releases the second installment in the EVERYBODY DJ video series Dance music pioneer A Guy Called Gerald discusses the cultural link between new technology and the evolution of electronic music Berlin, September 18, 2014 – Native Instruments today continues the EVERYBODY DJ video series with the second installment featuring electronic music legend A Guy Called Gerald. The video features Gerald describing how innovative technology plays an important role in defining DJ culture and how mobile apps like TRAKTOR DJ for iPad and iPhone are creating new performance possibilities and diversifying relationships to digital music. An icon in his own league, A Guy Called Gerald has been an instrumental figure in the development of techno, acid house, jungle, and drum and bass in the UK since the late 1980s. The video captures Gerald’s view on the close relationship between technology and electronic music – reflecting on previous audio limitations with vinyl, and how digital technology has changed how he listens to, DJs, and creates music. Filmed in London at the premier of RELEASE, a documentary on House Shuffling in Britain, the video shows Gerald as he explains why the physical manipulation of waveforms on apps like TRAKTOR DJ for iPad and iPhone has given rise to completely new ways of DJing. Gerald can be seen mixing, beat jumping, and loop slicing live with TRAKTOR DJ for iPad – a tool that has had a particular impact on his DJing. Still underway, the first video in the EVERYBODY DJ series introduced the MIX. WIN. BERLIN! competition where Native Instruments asks “What would you play?” Anyone can enter to win a VIP weekend in Berlin by recording and uploading a mix to Mixcloud using TRAKTOR DJ, and tagging it with the #whatwouldyouplay hashtag. -

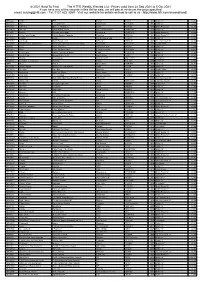

2021 Hard to Find the HTFR Weekly Wanted List

© 2021 Hard To Find The HTFR Weekly Wanted List - Prices valid from 28 Sep 2021 to 5 Oct 2021 If you have any of the records in this list for sale, we will pay at minimum the price specified email: [email protected] - Tel: 0121 622 3269 - Visit our website for details on how to sell to us - http://www.htfr.com/secondhand/ MR26666 100Hz EP3 Pacific FIC020 1999 British 12" £4.00 MR75274 16B Trail Of Dreams Stonehouse STR12008 1995 British 12" £2.00 MR18837 2 Funky 2 Brothers And Sisters Logic FUNKY2 1994 British Promo 12" £2.00 MR759025 3rd Core Mindless And Broken WEA International Inc. SAM00291 2000 British 12" £2.00 MR12656 4 Hero Cooking Up Ya Brain Reinforced RIVET1216 1992 British Promo 12" £2.00 MR14089 A Guy Called Gerald 28 Gun Badboy / Paranoia Columbia XPR1684 1992 British Promo 12" £8.00 MR169958 A Sides Punks Strictly Underground STUR74 1996 British 12" £4.00 MR353153 Aaron Carl Down (Resurrected) Wallshaker WMAC30 2009 American Import 12" £2.00 MR759966 Academy Of St. Martin-in-the-F Amadeus (Original Soundtrack Recording) Metronome 8251261ME 1984 Double Album £2.00 MR4926 Acen Close Your Eyes Production House PNT034 1992 British 12" £3.00 MR12863 Acen Trip Ii The Moon Part 3 Production House PNT042RX 1992 British 12" £3.00 MR16291 Age Of Love Age Of Love (Jam & Spoon) React 12REACT9 1992 British 12" £7.00 MR44954 Agent Orange Sounds Flakey To Me Agent Orange AO001 1992 British 12" £8.00 MR764680 Akasha Cinematique Wall Of Sound WALLLP016 1998 Vinyl Album £1.00 MR42023 Alan Braxe & Fred Falke Running Vulture VULT001 2000 French -

Retro Tendencies, Decay, and Haunted Media in Hybrid Electronic Music Adrien Ordonneau INSAM Journal of Contemporary Music, Art and Technology No

Retro Tendencies, Decay, and Haunted Media in Hybrid Electronic Music Adrien Ordonneau INSAM Journal of Contemporary Music, Art and Technology No. 3, Vol. II, December 2019, pp. 24–42. UDC 78.036:004 Adrien Ordonneau* Rennes 2 University Rennes, France RETRO TENDENCIES, DECAY, AND HAUNTED MEDIA IN HYBRID ELECTRONIC MUSIC Abstract: The consequences of new media and their manifestations in post-digital arts has deeply modified electronic music. Old and new sounds blend into each other to create a new aesthetic, defined in this article as hybrid electronic music. An analysis of this aesthetic helps us understand the impact of retro tendencies on the creative process. In order to have a sufficient amount of data, this article proposes a theoretical framework for the aesthetic which encompasses an analysis of the production’s material, how it is being used, live performances, and an emphasis on retro tendencies. The findings demonstrate the ambiguous and uncanny relationship electronic music can have with the past. One of the hypotheses of this article is the potential link between electronic music, future, and decay. Keywords: haunted, decay, organic, uncanny, regression, popular, alienation, body, paradox The future of humanity is constantly being questioned. From the biblical apocalypse to the big 2000 bug, numerous prophecies have foreseen chaos. I define “chaos” as an amalgam of numerous, confused, and disordered objects in an entangled state. Similarly, technological advance is continuously challenged in terms of its own evolution. In 1998, Nicholas Negroponte announced that “[T]he digital revolution is over”. Moore’s law is showing its limitations. Our fragile technological paradigm is threatening to stop, or worse, collapse. -

SANGAM, a CONFLUENCE Aditya Yogesh Desai, Masters of Fine Arts

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: SANGAM, A CONFLUENCE Aditya Yogesh Desai, Masters of Fine Arts, 2012 Thesis Directed by: Professor Howard Norman Department of English Sangam, Sanskrit for “confluence,” is a novel set across three storylines, all connected by a single ghazal poem, the evolution of which spans the lives and times of three men. In medieval India, Sufi poet Amir Khusrow arrives at the ruins of an ancient Hindu Temple, seeking inspiration and revival for his work; centuries later, at the turn of India’s independence from Britain, young lawyer Jayant finds his idealism tested in against the nation’s messy beginnings; in the present day, a young Indian-American disc jockey navigates the night club scene, hoping to become the modern music star. The novel is meant to mimic how music is sampled, re-appropriated, and remixed over time. In the same way songs are matched by a DJ for beats and melody, so too are the themes and emotional arcs of each man’s story line meant to echo one another, and resonate as a whole. SANGAM, A CONFLUENCE by Aditya Yogesh Desai Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Fine Arts 2012 Advisory Committee: Professor Howard Norman, Chair Professor Maud Casey Professor Gerald Gabriel Table of Contents Chapter 1 .................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2 ................................................................................................................................ -

Keyfinder V2 Dataset © Ibrahim Sha'ath 2014

KeyFinder v2 dataset © Ibrahim Sha'ath 2014 ARTIST TITLE KEY 10CC Dreadlock Holiday Gm 187 Lockdown Gunman (Natural Born Chillers Remix) Ebm 4hero Star Chasers (Masters At Work Main Mix) Am 50 Cent In Da Club C#m 808 State Pacifc State Ebm A Guy Called Gerald Voodoo Ray A A Tribe Called Quest Can I Kick It? (Boilerhouse Mix) Em A Tribe Called Quest Find A Way Ebm A Tribe Called Quest Vivrant Thing (feat Violator) Bbm A-Skillz Drop The Funk Em Aaliyah Are You That Somebody? Dm AC-DC Back In Black Em AC-DC You Shook Me All Night Long G Acid District Keep On Searching G#m Adam F Aromatherapy (Edit) Am Adam F Circles (Album Edit) Dm Adam F Dirty Harry's Revenge (feat Beenie Man and Siamese) G#m Adam F Metropolis Fm Adam F Smash Sumthin (feat Redman) Cm Adam F Stand Clear (feat M.O.P.) (Origin Unknown Remix) F#m Adam F Where's My (feat Lil' Mo) Fm Adam K & Soha Question Gm Adamski Killer (feat Seal) Bbm Adana Twins Anymore (Manik Remix) Ebm Afrika Bambaataa Mind Control (The Danmass Instrumental) Ebm Agent Sumo Mayhem Fm Air Sexy Boy Dm Aktarv8r Afterwrath Am Aktarv8r Shinkirou A Alexis Raphael Kitchens & Bedrooms Fm Algol Callisto's Warm Oceans Am Alison Limerick Where Love Lives (Original 7" Radio Edit) Em Alix Perez Forsaken (feat Peven Everett and Spectrasoul) Cm Alphabet Pony Atoms Em Alphabet Pony Clones Am Alter Ego Rocker Am Althea & Donna Uptown Top Ranking (2001 digital remaster) Am Alton Ellis Black Man's Pride F Aluna George Your Drums, Your Love (Duke Dumont Remix) G# Amerie 1 Thing Ebm Amira My Desire (Dreem Teem Remix) Fm Amirali -

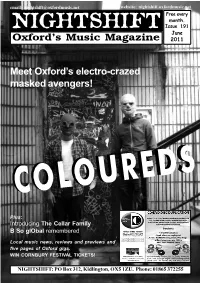

Issue 191.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 191 June Oxford’s Music Magazine 2011 Meet Oxford’s electro-crazed masked avengers! COLOUREDSCOLOUREDS Plus: Introducing The Cellar Family B So glObal remembered Local music news, reviews and previews and five pages of Oxford gigs. WIN CORNBURY FESTIVAL TICKETS! NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net COWLEY ROAD CARNIVAL However, we hope everyone will will be a South Park-only event understand that it is the right one this year after the organisers were to make in the financial unable to secure enough funding to circumstances.” cover the cost of staging the event For more info on Fiesta and on Cowley Road itself. Carnival, visit Carnival In South Park will go www.cowleyroadcarnival.co.uk ahead over the weekend of the 2nd- rd YOUNG KNIVES are among the latest set of acts to be confirmed for 3 July, with the Saturday night BBC OXFORD INTRODUCING Truck Festival. The local trio, who are currently on tour to promote event a fundraising fiesta headlined moves to a new day and time from th their new album, ‘Ornaments From The Silver Arcade’, and recently by Roots Manuva. this month. From May 29 the played an intimate set at Truck Store on Cowley Road as part of Carnival chairman John Hole dedicated local music show will go National Record Store Day, will join Gruff Rhys on the main stage on explained the decision to make this out on a Sunday at 9pm, moving the Saturday night. -

Sonic Warfare

SONIC WARFARE Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear Steve Goodman The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. For information about special quantity discounts, please e- mail special_sales@mitpress .mit .edu This book was set in Syntax and Minion by Graphic Composition, Inc. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Goodman, Steve. Sonic warfare : sound, aff ect, and the ecology of fear / Steve Goodman. p. cm. — (Technologies of lived abstraction) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN - - - - (hardcover : alk. paper) . Music—Acoustics and physics. Music—Social aspects. Music—Philosophy and aesthetics. I. Title. ML.G '.—dc 1998: A Conceptual Event 1 Some of these sonic worlds will secede from the mainstream worlds and some will be antagonistic towards it. —Black Audio Film Collective, The Last Angel of History () In an unconscious yet catalytic conceptual episode, the phrase sonic warfare fi rst wormed its way into memory sometime in the late s. The implantation had taken place during a video screening of the The Last Angel of History, produced by British artists, the Black Audio Film Collective. The video charted the coevo- lution of Afrofuturism: the interface between the literature of black science fi c- tion, from Samuel Delaney, Octavia Butler, and Ishmael Reed to Greg Tate and the history of Afro- diasporic electronic music, running from Sun Ra in jazz, Lee “Scratch” Perry in dub, and George Clinton in funk, right through to pioneers of Detroit techno (Juan Atkins, Derrick May, Carl Craig) and, from the U.K., jungle and drum’n’bass (A Guy Called Gerald, Goldie). -

Ethnoforgery and Outsider Afrofuturism Feature Article Trace Reddell University of Denver (US)

Ethnoforgery and Outsider Afrofuturism Feature Article Trace Reddell University of Denver (US) Abstract This essay detours from Afrofuturism proper into ethnological forgery and Outsider practices, foregrounding the issues of authenticity, authorship and identity which measure Afrofuturism’s ongoing relevance to technocultural conditions and the globally-scaled speculative imagination. The ethnological forgeries of the German rock group Can, the work of David Byrne and Brian Eno, and trumpeter Jon Hassell’s Fourth World volumes posit an “hybridity-at-the-origin” of Afrofuturism that deconstructs racial myths of identity and appropriation/exploitation. The self-reflective and critical nature of these projects foregrounds issues of origination through production strategies that combine ethnic instrumentation and techniques, voices sampled from radio and TV broadcast, and genre-mashing hybrids of rock and funk along with unconventional styles like ambient drone, minimalism, noise, free jazz, field recordings, and musique concrète. With original recordings and major statements of Afrofuturist theory in mind, I orchestrate a deliberately ill-fitting mixture of Slavoj Žižek’s critique of multiculturalism, Félix Guattari’s concept of “polyphonic subjectivity,” and Marcus Boon’s idea of shamanic “ethnopsychedelic montage” in order to argue for an Outsider Afrofuturism that works along the lines of an alternative modernity at the seam of subject identity and technocultural hybridization. In tune with the Fatherless sensibilities that first united black youth in Detroit (funk, techno) and the Bronx (hip-hop) with Germany’s post-WWII generation (Can’s krautrock, Kraftwerk’s electro), Outsider Afrofuturism opens up alternative routes toward understanding subjectivity and culture—through speculative sonic practices in particular—while maintaining social behaviors that reject multiculturalism’s artificial paternal origins, boundaries and lineages.