Last Angel of History Research, Writing, Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Among Us by Nina Runa Essendrop

1 . Among us By Nina Runa Essendrop A poetic and sensuous scenario about human loneliness and about the longing of the angels for the profound beauty which is found in every human life. 2 Preview Humans are ever present. They see the world in colors. They feel and they think and they walk on two feet. They touch the water and feel the cold softness of the surface. They gaze at the horizon and think deep thoughts about their existence. Humans feel the wind against their faces, they laugh and they cry and their pleading eyes seek for a meaning in the world around them. They breathe too fast and they forget to feel the ground under their feet or the invisible hand on their shoulder, which gently offers them comfort and peace. Angels exist among the humans. Invisible and untouchable they witness how humans live their lives. Their silent voices gently form mankind’s horizons, far away and so very very close that only children and dreamers will sense their presence. "Among us" is a poetic and sensuous scenario about a lonely human being, an angel who chooses the immediacy of mortal life, and an angel who continues to be the invisible guardian of mankind. It is a slow and thoughtful experience focussing on how beautiful, difficult and meaningful it is to be a human being. The scenario is played as a chamber larp and the players will be prepared for the play-style and tools through a workshop. The scenario is based on the film ”Wings of Desire” by Win Wender. -

The Second Try

The Second Try Jimmy Wolk Chapter I: The 12th Shinji Ikari, Third Children and designated pilot of Evangelion Unit-01, had just reached a new sync- ratio record. And as Rei Ayanami suspected, the former holder of this record, known as Asuka Langley Soryu, wasn't very pleased with this. So she didn't pay much attention to the rants of the Second Children, who made obviously ironical statements about the 'great, invincible Shinji' while holding herself; swaying in front of her locker. Instead, Rei finished changing from the plugsuit the pilots were supposed to wear during their time in the entry plugs of the EVAs or the test plugs, into her casual school uniform. As soon as she was done, she went silently for the door of the female pilots' changing room, whispered "Sayonara" and left. With the First Children gone, Asuka could finally release all the feelings that tensed up the last hours in a powerful... ...sigh. She still had problems to play this charade in front of everyone, and it seemed to only grow harder. She wasn't sure if she would be able to keep it up much longer at all. Not while these thoughts disturbed her mind; thoughts of all the things that happened... or will happen soon. Lost in her worries, she failed to notice someone entering the room, sneaking up to her and suddenly embracing her from behind; encircling her arms with his own. She tensed up noticeably as she felt the touch, even though (or maybe just because) she knew exactly who the stranger was. -

The Sunday Book of Poetry

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fe Wi ilkWMWM niiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii no THE GIFT OF Prof .Aubrey Tealdi iiiiuiiiiiiiiiiuiiiiiiiiiiiiMiiiiiuiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiuiHiiiiiiiiiiuiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii.il!!: tJU* A37f , k LONDON : R. CLAY, SON, AND TAYLOR, PRINTERS, BREAD STREET HILL. Fourth Thousand. THE SUNDAY BOOK OF POETRY SELECTED AND ARRANGED BY V,v ., .O" F^-A*! EX A N D E R AUTHOR OF "HYMNS FOR LITTLE CHILDREN," ETC. Jfambou srab Cambridge : MACMILLAN AND CO. 1865. A Taip in&e' when tonat v.... <lu: lie Ria sev ate Pi di . B IT- PREFACE The present volume will, it is hoped, be found to contain a selection of Sacred Poetry, of such a character as can be placed with profit and pleasure in the hands of intelligent children from eight to fourteen years of age, both on Sundays and at other times. It may be well for the Compiler to make some remarks upon the principles which have been adopted in the present selection. Dr. Johnson has said that " the word Sacred should never be applied but where some reference may be made to a higher Being, or where some duty is exacted, or implied." The Compiler be lieves she has selected few poems whose insertion may not be justified by this definition, though several perhaps may not be of such a nature as are popularly termed sacred. Those which appear under the division of the Incarnate Word, and of Praise, and Prayer, are of course in some cases directly hymns, and in all cases founded upon the great doctrines of the Christian faith, or upon the events of the Redeemer's life. -

2019-05-06 Catalog P

Pulp-related books and periodicals available from Mike Chomko for May and June 2019 Dianne and I had a wonderful time in Chicago, attending the Windy City Pulp & Paper Convention in April. It’s a fine show that you should try to attend. Upcoming conventions include Robert E. Howard Days in Cross Plains, Texas on June 7 – 8, and the Edgar Rice Burroughs Chain of Friendship, planned for the weekend of June 13 – 15. It will take place in Oakbrook, Illinois. Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like there will be a spring edition of Ray Walsh’s Classicon. Currently, William Patrick Maynard and I are writing about the programming that will be featured at PulpFest 2019. We’ll be posting about the panels and presentations through June 10. On June 17, we’ll write about this year’s author signings, something new we’re planning for the convention. Check things out at www.pulpfest.com. Laurie Powers biography of LOVE STORY MAGAZINE editor Daisy Bacon is currently scheduled for release around the end of 2019. I will be carrying this book. It’s entitled QUEEN OF THE PULPS. Please reserve your copy today. Recently, I was contacted about carrying the Armchair Fiction line of books. I’ve contacted the publisher and will certainly be able to stock their books. Founded in 2011, they are dedicated to the restoration of classic genre fiction. Their forté is early science fiction, but they also publish mystery, horror, and westerns. They have a strong line of lost race novels. Their books are illustrated with art from the pulps and such. -

The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 17 (Autumn 2018)

The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 17 (Autumn 2018) Contents ARTICLES Mother, Monstrous: Motherhood, Grief, and the Supernatural in Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s Médée Shauna Louise Caffrey 4 ‘Most foul, strange and unnatural’: Refractions of Modernity in Conor McPherson’s The Weir Matthew Fogarty 17 John Banville’s (Post)modern Reinvention of the Gothic Tale: Boundary, Extimacy, and Disparity in Eclipse (2000) Mehdi Ghassemi 38 The Ballerina Body-Horror: Spectatorship, Female Subjectivity and the Abject in Dario Argento’s Suspiria (1977) Charlotte Gough 51 In the Shadow of Cymraeg: Machen’s ‘The White People’ and Welsh Coding in the Use of Esoteric and Gothicised Languages Angela Elise Schoch/Davidson 70 BOOK REVIEWS: LITERARY AND CULTURAL CRITICISM Jessica Gildersleeve, Don’t Look Now Anthony Ballas 95 Plant Horror: Approaches to the Monstrous Vegetal in Fiction and Film, ed. by Dawn Keetley and Angela Tenga Maria Beville 99 Gustavo Subero, Gender and Sexuality in Latin American Horror Cinema: Embodiments of Evil Edmund Cueva 103 Ecogothic in Nineteenth-Century American Literature, ed. by Dawn Keetley and Matthew Wynn Sivils Sarah Cullen 108 Monsters in the Classroom: Essays on Teaching What Scares Us, ed. by Adam Golub and Heather Hayton Laura Davidel 112 Scottish Gothic: An Edinburgh Companion, ed. by Carol Margaret Davison and Monica Germanà James Machin 118 The Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies 17 (Autumn 2018) Catherine Spooner, Post-Millennial Gothic: Comedy, Romance, and the Rise of Happy Gothic Barry Murnane 121 Anna Watz, Angela Carter and Surrealism: ‘A Feminist Libertarian Aesthetic’ John Sears 128 S. T. Joshi, Varieties of the Weird Tale Phil Smith 131 BOOK REVIEWS: FICTION A Suggestion of Ghosts: Supernatural Fiction by Women 1854-1900, ed. -

Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic

‘Impossible Tales’: Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic Irene Bulla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Irene Bulla All rights reserved ABSTRACT ‘Impossible Tales’: Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic Irene Bulla This dissertation analyzes the ways in which monstrosity is articulated in fantastic literature, a genre or mode that is inherently devoted to the challenge of representing the unrepresentable. Through the readings of a number of nineteenth-century texts and the analysis of the fiction of two twentieth-century writers (H. P. Lovecraft and Tommaso Landolfi), I show how the intersection of the monstrous theme with the fantastic literary mode forces us to consider how a third term, that of language, intervenes in many guises in the negotiation of the relationship between humanity and monstrosity. I argue that fantastic texts engage with monstrosity as a linguistic problem, using it to explore the limits of discourse and constructing through it a specific language for the indescribable. The monster is framed as a bizarre, uninterpretable sign, whose disruptive presence in the text hints towards a critique of overconfident rational constructions of ‘reality’ and the self. The dissertation is divided into three main sections. The first reconstructs the critical debate surrounding fantastic literature – a decades-long effort of definition modeling the same tension staged by the literary fantastic; the second offers a focused reading of three short stories from the second half of the nineteenth century (“What Was It?,” 1859, by Fitz-James O’Brien, the second version of “Le Horla,” 1887, by Guy de Maupassant, and “The Damned Thing,” 1893, by Ambrose Bierce) in light of the organizing principle of apophasis; the last section investigates the notion of monstrous language in the fiction of H. -

Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture

AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISMAFROFUTURISM THE WORLD OF BLACK SCI-FI AND FANTASY CULTURE YTASHA L. WOMACK Chicago Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 3 5/22/13 3:53 PM AFROFUTURISM Afrofuturism_half title and title.indd 1 5/22/13 3:53 PM Copyright © 2013 by Ytasha L. Womack All rights reserved First edition Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism : the world of black sci-fi and fantasy culture / Ytasha L. Womack. — First edition. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61374-796-4 (trade paper) 1. Science fiction—Social aspects. 2. African Americans—Race identity. 3. Science fiction films—Influence. 4. Futurologists. 5. African diaspora— Social conditions. I. Title. PN3433.5.W66 2013 809.3’8762093529—dc23 2013025755 Cover art and design: “Ioe Ostara” by John Jennings Cover layout: Jonathan Hahn Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN Interior art: John Jennings and James Marshall (p. 187) Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 I dedicate this book to Dr. Johnnie Colemon, the first Afrofuturist to inspire my journey. I dedicate this book to the legions of thinkers and futurists who envision a loving world. CONTENTS Acknowledgments .................................................................. ix Introduction ............................................................................ 1 1 Evolution of a Space Cadet ................................................ 3 2 A Human Fairy Tale Named Black .................................. -

Paul Klee . Angelus Novus , 1920, Oil and Watercolor on Paper 31.8 X

PAUL KLEE. ANGELUS NOVUS , 1920, OIL AND WATERCO LO R ON PAPER , 31.8 X 24.2CM . ISRAEL MUSEUM , JERUSALEM (COURTESY OF CR E ATIVE COMMONS). What is the nature of history in John There are two important aspects to stay—presumably in the present painting, Akomfrah considers the Mothership Connection. Following Akomfrah’s 1995 documentary, The to this thesis that are relevant to (or perhaps even return to the story of the historical figure and this clue, the Data Thief, “[Surfs] Last Angel of History? One way to understanding the concept of history past)—to help mend the catastrophe blues legend, Robert Johnson. In across the internet of black culture, Akomfrah’s answer this question is to begin with in Akomfrah’s film: the location of before his feet. However, historical the very beginning of the film, the breaking into the vaults, breaking into the title. The Last Angel of History the storm and the angel’s desire materialism’s sense of history is narrator recites the famous story the rooms, and stealing fragments, Angel of is surely a reference to Walter to stay. Benjamin explains that oriented towards the future. That is of how Johnson learned to play the fragments from cyber-culture, Benjamin’s famous meditation on the storm’s origin is Paradise. In to say, each distinct historical event blues: “Robert Johnson sold his techno-culture, narrative-culture.”8 Paul Klee’s 1920 painting, Angelus Abrahamic religious traditions, builds on another toward a logical soul to the devil at the crossroads History Novus, in his own “Theses on the Paradise is the subject of various end based on material progress. -

Native Instruments Releases the Second Installment in the EVERYBODY DJ Video Series

Native Instruments releases the second installment in the EVERYBODY DJ video series Dance music pioneer A Guy Called Gerald discusses the cultural link between new technology and the evolution of electronic music Berlin, September 18, 2014 – Native Instruments today continues the EVERYBODY DJ video series with the second installment featuring electronic music legend A Guy Called Gerald. The video features Gerald describing how innovative technology plays an important role in defining DJ culture and how mobile apps like TRAKTOR DJ for iPad and iPhone are creating new performance possibilities and diversifying relationships to digital music. An icon in his own league, A Guy Called Gerald has been an instrumental figure in the development of techno, acid house, jungle, and drum and bass in the UK since the late 1980s. The video captures Gerald’s view on the close relationship between technology and electronic music – reflecting on previous audio limitations with vinyl, and how digital technology has changed how he listens to, DJs, and creates music. Filmed in London at the premier of RELEASE, a documentary on House Shuffling in Britain, the video shows Gerald as he explains why the physical manipulation of waveforms on apps like TRAKTOR DJ for iPad and iPhone has given rise to completely new ways of DJing. Gerald can be seen mixing, beat jumping, and loop slicing live with TRAKTOR DJ for iPad – a tool that has had a particular impact on his DJing. Still underway, the first video in the EVERYBODY DJ series introduced the MIX. WIN. BERLIN! competition where Native Instruments asks “What would you play?” Anyone can enter to win a VIP weekend in Berlin by recording and uploading a mix to Mixcloud using TRAKTOR DJ, and tagging it with the #whatwouldyouplay hashtag. -

Review and Herald for 1855

VIEt AD\nr4r1 GI...n[11UL AN]) SABBATH HERALD. ft no e is the Patience of the Sainte; Here arc they that keep the Commandments of God and the Penh of Jesue.' , Vo L . VII. ROCHESTER, N. Y., THIRD-DAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 1855. No. 6. to the disciples, says, "Go ye into all the world, natural eyes. There would then be no propriety for THE REVIEW AND HERALD and preach the gospel to every creature, and lo l God to say he would put his hand over Moses' face IS PUBLISHED I am with you alway, even unto the end of the while he passed by, (seemingly to prevent him from At South St. Paul-st., Stone's Block, world. Now, no one would contend that Christ seeing his face,) for he could not see him. Neither NO. 23, Third Floor. had been on the earth personally ever since the dis- do we conceive how an immaterial hand could ob- TERMS.—One Dollar for a Volume of ciples commenced to fulfill this commission. But struct the rays of light from passing to Moses' eyes. Numbers. 916 his Spirit has been on the earth; the Comforter that But if the position be true that God is immaterial, J. N. ANDREWS, }) Publishing lie promised to send. So in the same manner God and cannot be seen by the natural eye, the text R. F. COTTRELL, Committee. URIAH SMITH. manifests himself by his Spirit which is also the above is all superfluous. What sense is there in power through which he works. "But if the Spir- saying God put his hand over Moses' face, to prevent rirtancommunications, orders, and remittances should be addressed to ELD. -

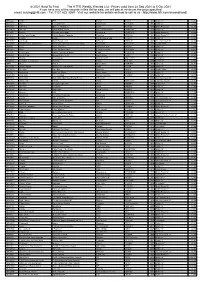

2021 Hard to Find the HTFR Weekly Wanted List

© 2021 Hard To Find The HTFR Weekly Wanted List - Prices valid from 28 Sep 2021 to 5 Oct 2021 If you have any of the records in this list for sale, we will pay at minimum the price specified email: [email protected] - Tel: 0121 622 3269 - Visit our website for details on how to sell to us - http://www.htfr.com/secondhand/ MR26666 100Hz EP3 Pacific FIC020 1999 British 12" £4.00 MR75274 16B Trail Of Dreams Stonehouse STR12008 1995 British 12" £2.00 MR18837 2 Funky 2 Brothers And Sisters Logic FUNKY2 1994 British Promo 12" £2.00 MR759025 3rd Core Mindless And Broken WEA International Inc. SAM00291 2000 British 12" £2.00 MR12656 4 Hero Cooking Up Ya Brain Reinforced RIVET1216 1992 British Promo 12" £2.00 MR14089 A Guy Called Gerald 28 Gun Badboy / Paranoia Columbia XPR1684 1992 British Promo 12" £8.00 MR169958 A Sides Punks Strictly Underground STUR74 1996 British 12" £4.00 MR353153 Aaron Carl Down (Resurrected) Wallshaker WMAC30 2009 American Import 12" £2.00 MR759966 Academy Of St. Martin-in-the-F Amadeus (Original Soundtrack Recording) Metronome 8251261ME 1984 Double Album £2.00 MR4926 Acen Close Your Eyes Production House PNT034 1992 British 12" £3.00 MR12863 Acen Trip Ii The Moon Part 3 Production House PNT042RX 1992 British 12" £3.00 MR16291 Age Of Love Age Of Love (Jam & Spoon) React 12REACT9 1992 British 12" £7.00 MR44954 Agent Orange Sounds Flakey To Me Agent Orange AO001 1992 British 12" £8.00 MR764680 Akasha Cinematique Wall Of Sound WALLLP016 1998 Vinyl Album £1.00 MR42023 Alan Braxe & Fred Falke Running Vulture VULT001 2000 French -

Popular Fiction 1814-1939: Selections from the Anthony Tino Collection

POPULAR FICTION, 1814-1939 SELECTIONS FROM THE ANTHONY TINO COLLECTION L.W. Currey, Inc. John W. Knott, Jr., Bookseller POPULAR FICTION, 1814-1939 SELECTIONS FROM THE THE ANTHONY TINO COLLECTION WINTER - SPRING 2017 TERMS OF SALE & PAYMENT: ALL ITEMS subject to prior sale, reservations accepted, items held seven days pending payment or credit card details. Prices are net to all with the exception of booksellers with have previous reciprocal arrangements or are members of the ABAA/ILAB. (1). Checks and money orders drawn on U.S. banks in U.S. dollars. (2). Paypal (3). Credit Card: Mastercard, VISA and American Express. For credit cards please provide: (1) the name of the cardholder exactly as it appears on your card, (2) the billing address of your card, (3) your card number, (4) the expiration date of your card and (5) for MC and Visa the three digit code on the rear, for Amex the for digit code on the front. SALES TAX: Appropriate sales tax for NY and MD added. SHIPPING: Shipment cost additional on all orders. All shipments via U.S. Postal service. UNITED STATES: Priority mail, $12.00 first item, $8.00 each additional or Media mail (book rate) at $4.00 for the first item, $2.00 each additional. (Heavy or oversized books may incur additional charges). CANADA: (1) Priority Mail International (boxed) $36.00, each additional item $8.00 (Rates based on a books approximately 2 lb., heavier books will be price adjusted) or (2) First Class International $16.00, each additional item $10.00. (This rate is good up to 4 lb., over that amount must be shipped Priority Mail International).