MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: CANADA Mapping Digital Media: Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Release – CHCH 2013 Upfront Announcements

Media Alert For Immediate Release June 11, 2013 60 YEARS STRONG! CHCH announces all that’s in store for Fall 2013 New shows and simulcasts this Fall cement CHCH’s position as a Top 5 station Mark Burnett’s latest creation SPIN OFF makes its world premiere on CHCH this Fall Approaching a significant milestone, CHCH gets ready to celebrate its 60th Anniversary! The return of a CHCH television classic – the new Tiny Talent Time hits the air in 2014! Parent company launches new division – Channel Zero Digital (Toronto, Canada) This morning at its 2013 Upfront Presentation, Channel Zero made a series of announcements and revealed the CHCH Fall 2013 Television Schedule. “2014 marks a significant year for CHCH. The station will celebrate 60 years on the air, and we’re heading into the new television season with plenty of momentum and a strong and proven simulcast schedule,” said Chris Fuoco, VP Sales & Marketing, Channel Zero. “CHCH has established itself as a top 5 station in Toronto and Ontario, and we’re excited about what our 60th year plans have in store for our viewers and advertisers.” CHCH Primetime this Fall New Shows CHCH has picked up exclusive rights to SPIN OFF from Executive Producer Mark Burnett (Survivor, Celebrity Apprentice, The Voice). “In a 30-minute game of trivia and chance SPIN OFF contestants win big or lose it all against their greatest adversary – The Wheel!” explained show host and Gemini-nominated Second City Alumnus Elvira Kurt during today’s announcements. SPIN OFF premieres this Fall and airs Wednesdays at 8pm. -

Siriusxm-Schedule.Pdf

on SCHEDULE - Eastern Standard Time - Effective: Sept. 6/2021 ET Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Saturday Sunday ATL ET CEN MTN PAC NEWS NEWS NEWS 6:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 3:00 Rewind The Doc Project The Next Chapter NEWS NEWS NEWS 7:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 4:00 Quirks & The Next Now or Spark Unreserved Play Me Day 6 Quarks Chapter Never NEWS What on The Cost of White Coat NEWS World 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 5:00 8:00 Pop Chat WireTap Earth Living Black Art Report Writers & Company The House 8:37 NEWS World 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 6:00 9:00 World Report The Current Report The House The Sunday Magazine 10:00 NEWS NEWS NEWS 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 7:00 Day 6 q NEWS NEWS NEWS 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 8:00 11:00 Because News The Doc Project Because The Cost of What on Front The Pop Chat News Living Earth Burner Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 12:00 The Cost of Living 12:00 11:00 10:00 9:00 Rewind Quirks & Quarks What on Earth NEWS NEWS NEWS 1:00 Pop Chat White Coat Black Art 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 10:00 The Next Quirks & Unreserved Tapestry Spark Chapter Quarks Laugh Out Loud The Debaters NEWS NEWS NEWS 2:00 Ideas in 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 11:00 Podcast Now or CBC the Spark Now or Never Tapestry Playlist Never Music Live Afternoon NEWS NEWS NEWS 3:00 CBC 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 12:00 Writers & The Story Marvin's Reclaimed Music The Next Chapter Writers & Company Company From Here Room Top 20 World This Hr The Cost of Because What on Under the NEWS NEWS 4:00 WireTap 5:00 4:00 3:00 2:00 1:00 Living News Earth Influence Unreserved Cross Country Check- NEWS NEWS Up 5:00 The Current -

The Honourable Christian Paradis, Canadian Minister of Industry and Minister of State to Ring the NASDAQ Stock Market Closing Bell

The Honourable Christian Paradis, Canadian Minister of Industry and Minister of State to Ring The NASDAQ Stock Market Closing Bell ADVISORY, Nov. 30, 2011 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- What: The Honourable Christian Paradis, Canadian Minister of Industry and Minister of State (Agriculture), will visit the NASDAQ MarketSite in New York City's Times Square to officially ring The NASDAQ Stock Market Closing Bell. Where: NASDAQ MarketSite — 4 Times Square — 43rd & Broadway — Broadcast Studio When: Thursday, December 1st, 2011 — 3:45 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. ET Contact: Richard Walker Director of Communications Office of the Honourable Christian Paradis Minister of Industry (613) 995-9001 NASDAQ MarketSite: Jen Knapp (212) 401-8916 [email protected] Feed Information: Fiber Line (Encompass Waterfront): 4463 Gal 3C/06C 95.05 degrees West 18 mhz Lower DL 3811 Vertical FEC 3/4 SR 13.235 DR 18.295411 MOD 4:2:0 DVBS QPSK Facebook and Twitter: For multimedia features such as exclusive content, photo postings, status updates and video of bell ceremonies please visit our Facebook page at: http://www.facebook.com/nasdaqomx For news tweets, please visit our Twitter page at: http://twitter.com/nasdaqomx Webcast: A live webcast of the NASDAQ Closing Bell will be available at: http://www.nasdaq.com/about/marketsitetowervideo.asx or http://social.nasdaqomx.com. Photos: To obtain a hi-resolution photograph of the Market Close, please go to http://www.nasdaq.com/reference/marketsite_events.stm and click on the market close of your choice. About Christian Paradis: Christian Paradis was named Minister of Industry and Minister of State (Agriculture) on May 18, 2011. -

Canada's Public Space

CBC/Radio-Canada: Canada’s Public Space Where we’re going At CBC/Radio-Canada, we have been transforming the way we engage with Canadians. In June 2014, we launched Strategy 2020: A Space for Us All, a plan to make the public broadcaster more local, more digital, and financially sustainable. We’ve come a long way since then, and Canadians are seeing the difference. Many are engaging with us, and with each other, in ways they could not have imagined a few years ago. Our connection with the people we serve can be more personal, more relevant, more vibrant. Our commitment to Canadians is that by 2020, CBC/Radio-Canada will be Canada’s public space where these conversations live. Digital is here Last October 19, Canadians showed us that their future is already digital. On that election night, almost 9 million Canadians followed the election results on our CBC.ca and Radio-Canada.ca digital sites. More precisely, they engaged with us and with each other, posting comments, tweeting our content, holding digital conversations. CBC/Radio-Canada already reaches more than 50% of all online millennials in Canada every month. We must move fast enough to stay relevant to them, while making sure we don’t leave behind those Canadians who depend on our traditional services. It’s a challenge every public broadcaster in the world is facing, and CBC/Radio-Canada is further ahead than many. Our Goal The goal of our strategy is to double our digital reach so that 18 million Canadians, one out of two, will be using our digital services each month by 2020. -

Cbc Radio One, Today

Stratégies gagnantes Auditoires et positionnement Effective strategies Audiences and positioning Barrera, Lilian; MacKinnon, Emily; Sauvé, Martin 6509619; 5944927; 6374185 [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Rapport remis au professeur Pierre C. Bélanger dans le cadre du cours CMN 4515 – Médias et radiodiffusion publique 14 juin 2014 TABLE OF CONTENT ABSTRACT ......................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 3 CBC RADIO ONE, TODAY ...................................................................... 4 Podcasting the CBC Radio One Channel ............................................... 6 The Mobile App for CBC Radio One ...................................................... 7 Engaging with Audiences, Attracting New Listeners ............................... 9 CBC RADIO ONE, TOMORROW ............................................................. 11 Tomorrow’s Audience: Millennials ...................................................... 11 Fishing for Generation Y ................................................................... 14 Strengthening Market-Share among the Middle-aged ............................ 16 Favouring CBC Radio One in Institutional Settings ................................ 19 CONCLUSION .................................................................................... 21 REFERENCES .................................................................................... -

Astral Media Affichage Affiche Ses Couleurs Et

MEDIA RELEASE Dozens of Additional Canadian Artists, Athletes, and Icons Announced for Historic STRONGER TOGETHER, TOUS ENSEMBLE Broadcast this Sunday – Justin Bieber, Mike Myers, Ryan Reynolds, Serge Ibaka, Avril Lavigne, Kiefer Sutherland, Geddy Lee, Dallas Green, Morgan Rielly, Dan & Eugene Levy, Catherine O’Hara & Annie Murphy, David Foster, Robbie Robertson, Charlotte Cardin, Burton Cummings, and Cirque du Soleil confirmed to appear in biggest multi-platform broadcast event in Canadian history – – Previously announced participants include Céline Dion, Michael Bublé, Bryan Adams, Shania Twain, Sarah McLachlan, Howie Mandel, Jann Arden, Barenaked Ladies, Rick Mercer, Alessia Cara, Russell Peters, and Connor McDavid – – All-star collection of more than two dozen artists join together in ensemble performance of timely and treasured classic to be released following broadcast – – StrongerTogetherCanada.ca and @strongercanada launch today – Tags: #StrongerTogether #TousEnsemble @strongercanada TORONTO (April 23, 2020) – More than four dozen big-name Canadians have signed on for the historic broadcast STRONGER TOGETHER, TOUS ENSEMBLE, it was announced today. Airing commercial-free Sunday, April 26 at 6:30 p.m. across all markets/7 p.m. NT and now on hundreds of platforms, Canadian artists, activists, actors, and athletes will share their stories of hope and inspiration in a national salute to frontline workers combatting COVID-19 during the 90-minute show. The unprecedented event, in support of Food Banks Canada, has become the biggest multi-platform broadcast in Canadian history, with 15 broadcasting groups led by Bell Media, CBC/Radio-Canada, Corus Entertainment, Groupe V Média, and Rogers Sports & Media presenting the star-studded show on hundreds of TV, radio, streaming, and on demand platforms (see broadcast details below). -

JOHN A. MACDONALD the Indispensable Politician

JOHN A. MACDONALD The Indispensable Politician by Alastair C.F. Gillespie With a Foreword by the Hon. Peter MacKay Board of Directors CHAIR Brian Flemming Rob Wildeboer International lawyer, writer, and policy advisor, Halifax Executive Chairman, Martinrea International Inc., Robert Fulford Vaughan Former Editor of Saturday Night magazine, columnist VICE CHAIR with the National Post, Ottawa Jacquelyn Thayer Scott Wayne Gudbranson Past President and Professor, CEO, Branham Group Inc., Ottawa Cape Breton University, Sydney Stanley Hartt MANAGING DIRECTOR Counsel, Norton Rose Fulbright LLP, Toronto Brian Lee Crowley, Ottawa Calvin Helin SECRETARY Aboriginal author and entrepreneur, Vancouver Lincoln Caylor Partner, Bennett Jones LLP, Toronto Peter John Nicholson Inaugural President, Council of Canadian Academies, TREASURER Annapolis Royal Martin MacKinnon CFO, Black Bull Resources Inc., Halifax Hon. Jim Peterson Former federal cabinet minister, Counsel at Fasken DIRECTORS Martineau, Toronto Pierre Casgrain Director and Corporate Secretary of Casgrain Maurice B. Tobin & Company Limited, Montreal The Tobin Foundation, Washington DC Erin Chutter Executive Chair, Global Energy Metals Corporation, Vancouver Research Advisory Board Laura Jones Janet Ajzenstat, Executive Vice-President of the Canadian Federation Professor Emeritus of Politics, McMaster University of Independent Business, Vancouver Brian Ferguson, Vaughn MacLellan Professor, Health Care Economics, University of Guelph DLA Piper (Canada) LLP, Toronto Jack Granatstein, Historian and former head of the Canadian War Museum Advisory Council Patrick James, Dornsife Dean’s Professor, University of Southern John Beck California President and CEO, Aecon Enterprises Inc., Toronto Rainer Knopff, Navjeet (Bob) Dhillon Professor Emeritus of Politics, University of Calgary President and CEO, Mainstreet Equity Corp., Calgary Larry Martin, Jim Dinning Prinicipal, Dr. -

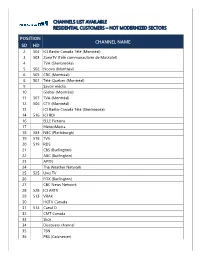

Channels List Available Residential

CHANNELS LIST AVAILABLE RESIDENTIAL CUSTOMERS – NOT MODERNIZED SECTORS POSITION CHANNEL NAME SD HD 2 504 ICI Radio-Canada Télé (Montréal) 3 503 ZoneTV (Télé communautaire de Maskatel) 4 TVA (Sherbrooke) 5 502 Noovo (Montréal) 6 505 CBC (Montréal) 8 501 Télé-Québec (Montréal) 9 Savoir média 10 Global (Montréal) 11 507 TVA (Montréal) 12 506 CTV (Montréal) 13 ICI Radio-Canada Télé (Sherbrooke) 14 516 ICI RDI 16 ELLE Fictions 17 MétéoMédia 18 583 NBC (Plattsburgh) 19 518 TV5 20 519 RDS 21 CBS (Burlington) 22 ABC (Burlington) 23 APTN 24 The Weather Network 25 525 Unis TV 26 FOX (Burlington) 27 CBC News Network 28 528 ICI ARTV 29 513 VRAK 30 HGTV Canada 31 514 Canal D 32 CMT Canada 33 Slice 34 Discovery channel 35 TSN 36 PBS (Colchester) 37 MAX 38 510 Canal Vie 39 508 LCN 40 Télétoon Français 41 Showcase 42 542 Télémag Québec 43 511 Historia 44 Évasion 45 515 Z télé 46 512 Séries Plus 47 CPAC Français 48 CPAC Anglais 50 BNN Bloomberg 52 552 ICI Explora 54 Assemblée Nationale du Québec 55 AMI-tv 56 AMI-télé 61 ICI Radio-Canada Télé (Québec) 64 TVA (Québec) 66 536 CASA 68 Citytv (Montréal) 75 PLANÈTE+ 78 MTV 79 Wild Pursuit Network 81 CBS (Seattle) 82 ABC (Seattle) 83 PBS (Seattle) 86 FOX (Seattle) 88 NBC (Seattle) 89 Télémagino 90 La Chaîne Disney 91 Yoopa 93 509 AddikTV 94 594 Investigation 95 Prise 2 97 MOI ET CIE 98 538 TVA Sports 99 RDS Info 100 539 RDS 2 101 YTV 102 CTV News Channel 103 Much Music 106 CTV Sci-Fi Channel 107 Vision TV 108 Teletoon Anglais 109 CTV Drama Channel 110 Fox Sports Racing 111 WGN (Chicago) 112 567 Sportsnet 360 -

Channel Guide Essentials

TM Optik TV Channel Guide Essentials Fort Grande Medicine Vancouver / Kelowna / Prince Dawson Victoria / Campbell Essential Channels Call Sign Edmonton Lloydminster Red Deer Calgary Lethbridge Kamloops Quesnel Cranbrook McMurray Prairie Hat Whistler Vernon George Creek Nanaimo River ABC Seattle KOMODT 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 131 AMI-audio* AMIPAUDIO 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 889 AMI-télé* AMITL 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 2288 AMI-tv* AMIW 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 APTN (West)* ATPNP 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 9125 — APTN HD* APTNHD 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 125 — BC Legislative TV* BCLEG — — — — — — — — 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 843 CBC Calgary* CBRTDT 100 100 100 CBC Edmonton* CBXTDT 100 100 — 100 100 CBC Lloydminster* CKSADT — — 100 — — — — — — — — — — — — — — CBC News Network CBNEWHD 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 800 CBC Vancouver* CBUTDT 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 100 CBS Seattle KIRODT 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 133 CFJC* CFJCDT — — — — — — — — — 115 106 — — — — — — CHAT* CHATDT — — — — — — — 122 — — — — — — — — — CHEK* CHEKDT — — — — — — — — 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 121 City Calgary* CKALDT 106 106 106 — City Edmonton* CKEMDT 106 106 106 106 106 — City Vancouver* CKVUDT 106 106 — 106 106 106 -

Independent Broadcaster Licence Renewals

February 15, 2018 Filed Electronically Mr. Chris Seidl Secretary General Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0N2 Dear Mr. Seidl: Re: Select broadcasting licences renewed further to Broadcasting Notice of Consultation CRTC 2017-183: Applications 2017-0821-5 (Family Channel), 2017-0822-3 (Family CHRGD), 2017- 0823-1 (Télémagino), 2017-0841-3 (Blue Ant Television General Partnership), 2017-0824-9 (CHCH-DT), 2017-0820-8 (Silver Screen Classics), 2017-0808-3 (Rewind), and 2017-0837-2 (Knowledge). The Writers Guild of Canada (WGC) is the national association representing approximately 2,200 professional screenwriters working in English-language film, television, radio, and digital media production in Canada. The WGC is actively involved in advocating for a strong and vibrant Canadian broadcasting system containing high-quality Canadian programming. Given the WGC’s nature and membership, our comments are limited to the applications of those broadcasters who generally commission programming that engages Canadian screenwriters, and in particular those who significantly invest in programs of national interest (PNI). The WGC conditionally supports the renewal of the above-noted services, subject to our comments below. Executive Summary ES.1 The Commission set out its general approach to Canadian programming expenditure (CPE) and PNI requirements in Broadcasting Regulatory Policy CRTC 2015-86, Let’s Talk TV: The way forward - Creating compelling and diverse Canadian programming (the Create Policy). In it, the Commission was clear that CPE was a central pillar of the regulatory policy framework for Canadian television broadcasting, and that the guiding principle for setting CPE levels for independent broadcasters would be historical spending levels. -

Competing in a Global Innovation Economy: the Current State of R&D

COMPETING IN A GLOBAL INNOVATION ECONOMY: THE CURRENT STATE OF R&D IN CANADA Expert Panel on the State of Science and Technology and Industrial Research and Development in Canada Science Advice in the Public Interest COMPETING IN A GLOBAL INNOVATION ECONOMY: THE CURRENT STATE OF R&D IN CANADA Expert Panel on the State of Science and Technology and Industrial Research and Development in Canada ii Competing in a Global Innovation Economy: The Current State of R&D in Canada THE COUNCIL OF CANADIAN ACADEMIES 180 Elgin Street, Suite 1401, Ottawa, ON, Canada K2P 2K3 Notice: The project that is the subject of this report was undertaken with the approval of the Board of Directors of the Council of Canadian Academies (CCA). Board members are drawn from the Royal Society of Canada (RSC), the Canadian Academy of Engineering (CAE), and the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences (CAHS), as well as from the general public. The members of the expert panel responsible for the report were selected by the CCA for their special competencies and with regard for appropriate balance. This report was prepared for the Government of Canada in response to a request from the Minister of Science. Any opinions, findings, or conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors, the Expert Panel on the State of Science and Technology and Industrial Research and Development in Canada, and do not necessarily represent the views of their organizations of affiliation or employment, or the sponsoring organization, Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Council of Canadian Academies. -

Canada's Antidumping and Safeguard Policies: Overt and Subtle Forms Of

Revised version forthcoming in The World Economy Canada’s Antidumping and Safeguard Policies: Overt and Subtle Forms of Discrimination Chad P. Bown† Brandeis University & The Brookings Institution This Draft: February 2007 (Original draft: April 2005) Abstract Like many countries in the international trading system, Canada repeatedly faces political pressure from industries seeking protection from import competition. I examine Canadian policymakers’ response to this pressure within the economic environment created by its participation in discriminatory trade agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). In particular, I exploit new sources of data on Canada’s use of potentially WTO-consistent import-restricting policies such as antidumping, global safeguards, and a China-specific safeguard. I illustrate subtle ways in which Canadian policymakers may be structuring the application of such policies so as to reinforce the discrimination inherent in Canada’s external trade policy because of the preferences granted to the United States and Mexico through NAFTA. JEL No. F13 Keywords: Canada, trade policy, antidumping, safeguards, MFN, WTO † Correspondence: Department of Economics and International Business School, MS 021, Brandeis University, PO Box 549110, Waltham, MA, 02454-9110 USA. tel: 781-736-4823, fax: 781-736-2269, email: [email protected], web: http://www.brandeis.edu/~cbown/. I gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Centre for International Governance Innovation. I thank Rachel McCulloch for comments