G.F Handel—Messiah Internationalism in Opera Was

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

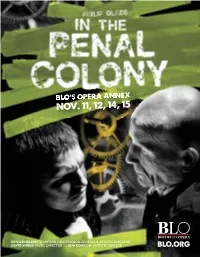

2015 in the Penal Colony Program

ESTHER NELSON, STANFORD CALDERWOOD GENERAL & ARTISTIC DIRECTOR DAVID ANGUS, MUSIC DIRECTOR | JOHN CONKLIN, ARTISTIC ADVISOR Rodolfo (Jesus Garcia) and Mimi (Kelly Kaduce) in Boston Lyric Opera’s 2015 production of La Bohème. This holiday season, share your love of opera with the ones you love. BLO off ers packages and gift certifi cates CHARLES ERICKSON T. to make your holiday shopping simple! T. CHARLES ERICKSON T. WELCOME TO THE SEVENTH IN OUR OPERA ANNEX SERIES, which is increasingly attracting national and international attention. Installing opera in non-conventional spaces has sparked a curiosity in the art. The challenges of these spaces are many and due to opera’s inherent demands: natural acoustics (since we do not amplify), adequate performance and production space, audience comfort and social space, location accessibility, parking, safety, and especially important in New England, adequate heat. Our In the Penal Colony comes amid questions and debate on the performance spaces and theatrical environment in Boston. For us, the questions include … why is Boston the only one of the top ten U.S. cities without a home suitable for opera? What are sustainable models to support new performance venues and/or preserve historic theaters? As you may have heard, BLO decided not to renew its agreement with the JesusJJesus GarciaGGarcia as RRoRodolfodldolffo Shubert Theatre after this Season. The reasons are many and complex, but suffi ce in La Bohème it to say that we made an important business and artistic decision. BLO is dedicated to spending signifi cantly more of our budget on direct artistic and production expenses and providing our patrons with a new level of service and comfort. -

A Critical Analysis of the Libretto in Handel's Messiah

Augustana College Augustana Digital Commons 2020 Festschrift: Georg Frideric Handel's "Messiah" Festschriften Fall 12-9-2020 Lost in Translation: A Critical Analysis of the Libretto in Handel's Messiah Jordan Lehto Augustana College, Rock Island Illinois Aaron Escamilla Augustana College, Rock Island Illinois Eden H. Nimietz Augustana College, Rock Island Illinois Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/muscfest2020 Part of the Composition Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Yiddish Language and Literature Commons Augustana Digital Commons Citation Lehto, Jordan; Escamilla, Aaron; and Nimietz, Eden H.. "Lost in Translation: A Critical Analysis of the Libretto in Handel's Messiah" (2020). 2020 Festschrift: Georg Frideric Handel's "Messiah". https://digitalcommons.augustana.edu/muscfest2020/2 This Student Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Festschriften at Augustana Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2020 Festschrift: Georg Frideric Handel's "Messiah" by an authorized administrator of Augustana Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lost in Translation: A Critical Analysis of the Libretto in Handel’s Messiah Aaron Escamilla Jordan Lehto Eden Nimietz Augustana College MUSC-311--Styles and Literature of Music I November 9, 2020 Escamilla, Lehto, Nimietz 2 Abstract Handel’s Messiah is renowned for its lush sound and richly developed message regarding the rejoicing of Christians and the celebration of religion through their faith in a divine savior. Not only is the full oratorio performed by countless ensembles every year, but many scholars have spent months, and even years, poring over its libretto. -

Handel Rinaldo Tuesday 13 March 2018 6.30Pm, Hall

Handel Rinaldo Tuesday 13 March 2018 6.30pm, Hall The English Concert Harry Bicket conductor/harpsichord Iestyn Davies Rinaldo Jane Archibald Armida Sasha Cooke Goffredo Joélle Harvey Almirena/Siren Luca Pisaroni Argante Jakub Józef Orli ´nski Eustazio Owen Willetts Araldo/Donna/Mago Richard Haughton Richard There will be two intervals of 20 minutes following Act 1 and Act 2 Part of Barbican Presents 2017–18 We appreciate that it’s not always possible to prevent coughing during a performance. But, for the sake of other audience members and the artists, if you feel the need to cough or sneeze, please stifle it with a handkerchief. Programme produced by Harriet Smith; printed by Trade Winds Colour Printers Ltd; advertising by Cabbell (tel 020 3603 7930) Please turn off watch alarms, phones, pagers etc during the performance. Taking photographs, capturing images or using recording devices during a performance is strictly prohibited. If anything limits your enjoyment please let us know The City of London during your visit. Additional feedback can be given Corporation is the founder and online, as well as via feedback forms or the pods principal funder of located around the foyers. the Barbican Centre Welcome Tonight we welcome back Harry Bicket as delighted by the extravagant magical and The English Concert for Rinaldo, the effects as by Handel’s endlessly inventive latest instalment in their Handel opera music. And no wonder – for Rinaldo brings series. Last season we were treated to a together love, vengeance, forgiveness, spine-tingling performance of Ariodante, battle scenes and a splendid sorceress with a stellar cast led by Alice Coote. -

The Time Is Now Thethe Timetime Isis Nownow Music Has the Power to Inspire, to Change Lives, to Illuminate Perspective, 20/21 SEASON and to Shift Our Vantage Point

20/21 SEASON The Time Is Now TheThe TimeTime IsIs NowNow Music has the power to inspire, to change lives, to illuminate perspective, 20/21 SEASON and to shift our vantage point. featuring FESTIVAL Your seats are waiting. Voices of Hope: Artists in Times of Oppression An exploration of humankind’s capacity for hope, courage, and resistance in the face of the unimaginable PERSPECTIVES Rhiannon Giddens “… an electrifying artist …” —Smithsonian PERSPECTIVES Yannick Nézet-Séguin “… the greatest generator of energy on the international podium …” —Financial Times PERSPECTIVES Jordi Savall “… a performer of genius but also a conductor, a scholar, a teacher, a concert impresario …” —The New Yorker DEBS COMPOSER’S CHAIR Andrew Norman “… the leading American composer of his generation ...” —Los Angeles Times Left: Youssou NDOUR On the cover: Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla carnegiehall.org/subscribe | 212-247-7800 Photos: NDOUR by Jack Vartoogian, Gražinytė-Tyla by Benjamin Ealovega. Box Office at 57th and Seventh Rafael Pulido Some of the most truly inspiring music CONTENTS you’ll hear this season—or any other season—at Carnegie Hall was written in response to oppressive forces that have 3 ORCHESTRAS ORCHESTRAS darkened the human experience throughout history. Perspectives: Voices of Hope: Artists in Times of Oppression takes audiences Yannick Nézet-Séguin on a journey unique among our festivals for the breadth of music 12 these courageous artists employed—from symphonies to jazz to Debs Composer’s popular songs and more. This music raises the question of why, 13 Chair: Andrew Norman no matter how horrific the circumstances, artists are nonetheless compelled to create art; and how, despite those circumstances, 28 Zankel Hall Center Stage the art they create can be so elevating. -

This Is Normal Text

AN EXAMINATION OF WORKS FOR SOPRANO: “LASCIA CH’IO PIANGA” FROM RINALDO, BY G.F. HANDEL; NUR WER DIE SEHNSUCHT KENNT, HEISS’ MICH NICHT REDEN, SO LASST MICH SCHEINEN, BY FRANZ SCHUBERT; AUF DEM STROM, BY FRANZ SCHUBERT; SI MES VERS AVAIENT DES AILES, L’ÉNAMOURÉE, A CHLORIS, BY REYNALDO HAHN; “ADIEU, NOTRE PETITE TABLE” FROM MANON, BY JULES MASSENET; HE’S GONE AWAY, THE NIGHTINGALE, BLACK IS THE COLOR OF MY TRUE LOVE’S HAIR, ADAPTED AND ARRANGED BY CLIFFORD SHAW; “IN QUELLE TRINE MORBIDE” FROM MANON LESCAUT, BY GIACOMO PUCCINI by ELIZABETH ANN RODINA B.M., KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY, 2006 A REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2008 Approved by: Major Professor Dr. Jennifer Edwards Copyright ELIZABETH ANN RODINA 2008 Abstract This report consists of extended program notes and translations for programmed songs and arias presented in recital by Elizabeth Ann Rodina on April 22, 2008 at 7:30 p.m. in All Faith’s Chapel on the Kansas State University campus. Included on the recital were works by George Frideric Handel, Franz Schubert, Reynaldo Hahn, Jules Massenet, Clifford Shaw, and Giacomo Puccini. The program notes include biographical information about the composers and a textual and musical analysis of their works. Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ vi List of Tables .............................................................................................................................. -

Così Fan Tutte Cast Biography

Così fan tutte Cast Biography (Cahir, Ireland) Jennifer Davis is an alumna of the Jette Parker Young Artist Programme and has appeared at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden as Adina in L’Elisir d’Amore; Erste Dame in Die Zauberflöte; Ifigenia in Oreste; Arbate in Mitridate, re di Ponto; and Ines in Il Trovatore, among other roles. Following her sensational 2018 role debut as Elsa von Brabant in a new production of Lohengrin conducted by Andris Nelsons at the Royal Opera House, Davis has been propelled to international attention, winning praise for her gleaming, silvery tone, and dramatic characterisation of remarkable immediacy. (Sacramento, California) American Mezzo-soprano Irene Roberts continues to enjoy international acclaim as a singer of exceptional versatility and vocal suppleness. Following her “stunning and dramatically compelling” (SF Classical Voice) performances as Carmen at the San Francisco Opera in June, Roberts begins the 2016/2017 season in San Francisco as Bao Chai in the world premiere of Bright Sheng’s Dream of the Red Chamber. Currently in her second season with the Deutsche Oper Berlin, her upcoming assignments include four role debuts, beginning in November with her debut as Urbain in David Alden’s new production of Les Huguenots led by Michele Mariotti. She performs in her first Ring cycle in 2017 singing Waltraute in Die Walküre and the Second Norn in Götterdämmerung under the baton of Music Director Donald Runnicles, who also conducts her role debut as Hänsel in Hänsel und Gretel. Additional roles for Roberts this season include Rosina in Il barbiere di Siviglia, Fenena in Nabucco, Siebel in Faust, and the title role of Carmen at Deutsche Oper Berlin. -

Handel's Messiah

Handel’s Messiah THE COMBINED VOICES OF ABERDEEN BACH CHOIR & ABERDEEN CHORAL SOCIETY Conductor: Peter Parfitt Aberdeen Sinfonietta Leader: Bryan Dargie Handel’s Messiah Soprano: Judith Howarth Counter-Tenor: Nicholas Spanos Tenor: Nicholas Mulroy Bass: Dominic Barberi Sunday 15 December 2019 at 7.00pm The Music Hall Aberdeen www.aberdeenbachchoir.com Charity Number: SC008609 www.aberdeenchoral.org.uk Charity number: SCO05414 PB 1 Handel’s Messiah Handel’s Messiah And is it true? And is it true, this most tremendous tale of all? A baby in an ox’s stall? The maker of the stars and sea, become a child, on Earth, for me? Sir John Betjeman O Virgin of virgins, how shall this be? For neither before Thee was any like unto Thee, nor shall there be any after. Daughters of Jerusalem, why marvel ye at me? The thing which ye behold is a divine mystery. Antiphon for Christmas Eve MESSIAH Messiah is a biblical oratorio by George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) for SATB soloists, SATB chorus, orchestra and continuo. It was written during a three-week period in August/September 1741, and given its first performance in Dublin, on April 13th 1742 at the New Music Hall in Fishamble Street. The first London performance was a year later in Covent Garden at Easter in 1743. Originally intended as an Easter offering, Messiah these days is as bound up with Christmas as tinsel and mince pies. It is one of only two oratorios by Handel where the entire text is taken from the bible, the other being Israel in Egypt, written in 1739. -

DISTRICT AUDITIONS THURSDAY, JANUARY 21, 2021 the 2020 National Council Finalists Photo: Fay Fox / Met Opera

NATIONAL COUNCIL 2020–21 SEASON ARKANSAS DISTRICT AUDITIONS THURSDAY, JANUARY 21, 2021 The 2020 National Council Finalists photo: fay fox / met opera CAMILLE LABARRE NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS chairman The Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions program cultivates young opera CAROL E. DOMINA singers and assists in the development of their careers. The Auditions are held annually president in 39 districts and 12 regions of the United States, Canada, and Mexico—all administered MELISSA WEGNER by dedicated National Council members and volunteers. Winners of the region auditions executive director advance to compete in the national semifinals. National finalists are then selected and BRADY WALSH compete in the Grand Finals Concert. During the 2020–21 season, the auditions are being administrator held virtually via livestream. Singers compete for prize money and receive feedback from LISETTE OROPESA judges at all levels of the competition. national advisor Many of the world’s greatest singers, among them Lawrence Brownlee, Anthony Roth Costanzo, Renée Fleming, Lisette Oropesa, Eric Owens, and Frederica von Stade, have won National Semifinals the Auditions. More than 100 former auditioners appear appear on the Met roster each season. Sunday, May 9, 2021 The National Council is grateful to its donors for prizes at the national level and to the Tobin Grand Finals Concert Endowment for the Mrs. Edgar Tobin Award, given to each first-place region winner. Sunday, May 16, 2021 Support for this program is generously provided by the Charles H. Dyson National Council The Semifinals and Grand Finals are Audition Program Endowment Fund at the Metropolitan Opera. currently scheduled to take place at the Met. -

BRIDGING the GAP Transitioning Vocalists from Academia to Career DMA Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requiremen

BRIDGING THE GAP Transitioning Vocalists from Academia to Career DMA Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Laura Michele Portune Cordell, B.A., M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2011 Committee: Robin Rice, Advisor Joseph Duchi Jere Forsythe Copyright by Laura Michele Portune Cordell 2011 Abstract Each year, promising students graduate from universities with degree in hand and sights set on a career in the arts but without the necessary information to achieve this goal. In a demanding, competitive field such as vocal performance, additional preparation and knowledge can make the difference between success and missed opportunities. Bridging the Gap is intended to provide information, teach necessary skills, and act as a resource for talented students transitioning into the professional world. It draws from information learned in academia and integrates it with information necessary for a career in the music industry. By accumulating past experience, advice from professionals in the field, and common expectations, students can use this information to better prepare themselves and gain an edge for a professional career in the arts. Although intended specifically for vocal performance majors in classical voice, many of the topics in this document are applicable to other instruments or fields in the realm of music. This information can serve as a graduate level class text on preparatory career information for students entering a professional career in voice, or can be useful to an individual looking to further his/her own development. -

Handel's Orlando

INDEPENDENT OPERA presents Handel’s Orlando Saturday 21 June 2008, 7pm Wigmore Hall Welcome Messages from Independent Opera It gives me great pleasure to welcome Independent Opera to INDEPENDENT OPERA at Sadler’s Wells was created in 2005 Wigmore Hall. I salute this valuable young organisation and all to provide a London performance platform for talented young it has achieved over such a short timescale. directors, designers, singers and others involved in the staging and performance of opera. We are delighted to partner with Independent Opera for the Wigmore Hall / Independent Opera Voice Fellowship and Building on the success of our first two productions, I applaud the pioneering work of Independent Opera’s INDEPENDENT OPERA Artist Support was launched in 2007. extensive fellowship programme as well as its commitment to This is a comprehensive programme of fellowships and a wide range of repertoire. scholarships designed to help promising young artists in the period immediately after their formal education ends. It funds I hope that you enjoy tonight’s performance of Orlando. singing lessons, coaching sessions and other activities that will help them make their way professionally. Our partnership with Wigmore Hall is particularly rewarding and provides a fellowship for a singer intent on pursuing a career in both opera and song. We welcome enquiries from individuals interested in sponsoring a fellowship. More information about Artist Support can be found at the back of this programme. John Gilhooly Director We hope you enjoy this evening’s performance of musical Wigmore Hall extracts from our 2006 production of Orlando. Anna Gustafson Director of Operations & Chief Executive, Artist Support INDEPENDENT OPERA at Sadler’s Wells Honorary Patrons It is with great pleasure that we present this performance DENT O EN PE Laurence Cummings EP R of Orlando at Wigmore Hall tonight.