Global Mental Health and Schizophrenia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Mental Health

global mental health POLICY AND SYSTEMS REVIEW Reducing the stigma of mental illness H. Stuart* Centre for Health Services and Policy Research, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada Global Mental Health (2016), 3, e17, page 1 of 14. doi:10.1017/gmh.2016.11 This paper presents a narrative review of anti-stigma programming using examples from different countries to under- stand and describe current best practices in the field. Results highlight the importance of targeting the behavioural out- comes of the stigmatization process (discrimination and social inequity), which is consistent with rights-based or social justice models that emphasize social and economic equity for people with disabilities (such as equitable access to ser- vices, education, work, etc.). They also call into question large public education approaches in favour of more targeted contact-based interventions. Finally, to add to the research base on best practices, anti-stigma programs are encouraged to create alliances with university researchers in order to critically evaluate their activities and build better, evidence informed practices. Received 26 May 2015; Revised 8 March 2016; Accepted 27 March 2016 Key words: Mental illness, stigma, stigma reduction. Introduction Despite growing recognition of the burden asso- ciated with mental illnesses, and the availability of The public health importance of mental disorders has cost-effective treatments, they are not yet afforded the been highlighted by the Global Burden of Disease same policy or program priority as comparably dis- study, which catapulted mental health promotion abling physical conditions. The most recent World and prevention onto the global public health stage. In Health Organization Mental Health Atlas clearly dem- 1990, five of the top ten leading causes of disability onstrates the inadequacies of mental health treatment worldwide were from mental illnesses, accounting for infrastructure worldwide. -

Advancing Mental Health As a Global Health Priority

1 Public Health Reviews, Vol. 35, No 1 Towards a Healthier 2020: Advancing Mental Health as a Global Health Priority Kathleen M. Pike, PhD,1 Ezra Susser, MD, DrPH,1 Sandro Galea, MD, DrPH,1 Harold Pincus, MD1 ABSTRACT Mental and behavioral disorders account for approximately 7.4 percent of the global burden of disease and represent the leading cause of disability worldwide. Intricately connected to educational achievement, overall health outcomes, and economic prosperity, mental and behavioral disorders have nonetheless largely been disregarded within the global health agenda. Recent efforts that more fully quantify the burden of mental and behavioral disorders, coupled with accumulating data of evidence-based approaches that successfully treat these disorders, even in low resource communities, serve as a cornerstone for envisioning a new era that prioritizes and integrates mental health in global health and development. A healthier 2020 depends on global collaboration, improved classification systems, expanded research networks that inform policy and practice globally, and innovative strategies to build capacity in terms of workforce and health care delivery systems. This work will require vigilance to combat ongoing stigma and vision to anticipate global demographic trends of an increasingly urban and ageing population. Such efforts have the potential to transform the lives of hundreds of millions of people around the globe. Key Words: Mental health, global health, behavioral disorders, disease burden, policy Recommended Citation: Pike KM, Susser E, Galea S, Pincus H. Towards a healthier 2020: advancing mental health as a global health priority. Public Health Reviews. 2013;35: epub ahead of print. 1 Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons, and Department of Epidemiology, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, USA. -

Mental Health for Global Prosperity: We Cannot Afford to Ignore the Impact of Mental Health on the Global Economy

Policy brief January 2019 Mental health for global prosperity: We cannot afford to ignore the impact of mental health on the global economy. Summary: It is #TimeToAct Mental ill-health lowers quality of life, depletes personal and family finances, feeds into the cycle of poverty, and has a potentially devastating impact on the global economy. Every year, 12 billion working days are lost due to mental illness. Between 2010-2030, this will cost $16 USD trillion in lost economic output— more than cancer, diabetes, and respiratory diseases combined. Cost-effective solutions exist, even for low-resource settings, but funding has not been made available to implement them. While mental illness is responsible for 13% of the global burden of disease, countries spend an average of less than 2% of their health budgets on mental health, and less than 1% of international aid for health goes toward mental health. As a result, we are missing out on the 4-fold return on investment in care for common mental illnesses like depression. If we do not act urgently to improve mental health—by promoting good mental health, preventing mental illness, and providing adequate mental health care— we put our personal well-being, businesses and economies at risk. Key Recommendations • Governments must deliver on commitments under the WHO Mental Health Action Plan, Sustainable Development Goals and Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. • Employers should include mental health in their organizational strategies, proactively identifying risks to mental wellbeing in the workplace and providing necessary support to those who need it. • Funders should increase aid for mental health prevention, promotion and care with a focus on implementation and scale-up to maximize potential return on investment. -

Alcohol Use and Mental Health in Developing Countries

Alcohol Use and Mental Health in Developing Countries VIKRAM PATEL, PHD This paper provides an overview of mental health and alcohol use in developing countries. The review shows that mental disorders are common and pose a significant burden on the health of developing nations. There are close associations between poor mental health and other public health and social development priorities. Although the overall use of alcohol at the population level is relatively low, with high abstention rate, drinking patterns among those who do drink are often hazardous. The consumption of alcohol is heavily gendered and is characterized by a high proportion of hazardous drinking among men. Hazardous drinkers do not only consume large amounts of alcohol, but also do so in high-risk patterns, such as drinking alone and bingeing. Hazardous drinking is associated with depressive and anxiety disorders as well as suicide and domestic violence. The limited evidence base suggests that moderate or casual drinking is not associ- ated with social or health hazards; any likely benefits of moderate drinking for mental health have not been studied in developing countries. The implications of this evidence base for future research and policy are discussed. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:S87–S92. Ó 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. KEY WORDS: Mental Health, Developing Countries, Alcohol Abuse, Comorbidity. INTRODUCTION MENTAL HEALTH IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES This paper assesses evidence of mental health harm and ben- At any given time, about 10% of the adult population glob- efits associated with drinking alcohol in the context of de- ally and about one in three adults attending a primary health veloping countries. -

Piloting Self-Help Groups for Alcohol Use Disorders in Saint Vincent

ORIGINAL RESEARCH Piloting Self-Help Groups for Alcohol Use Disorders in Saint Vincent/Grenadines Antonia Chen, MS, Ynolde Smart, RN, SCRM, PHN, Amrie Morris-Patterson, MBBS, DM, and Craig L. Katz, MD ABSTRACT Background: Although alcohol consumption is recognized as a global problem, little research to date explores treatment options for alcohol use disorders in developing nations. Given the scarce mental health resources available in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, community self-help programming for alcohol use disorders could potentially provide an important complement to the existing mental health services. Objective: The aim of this study was to gather baseline data on knowledge and attitudes toward alcohol consumption among community members, and subsequently, to pilot self-help rehabilitation programs for alcohol use disorders, while determining factors that affect the feasibility and sustainability of such programs. Methods: Focus groups were conducted in 3 communities to discuss community perceptions of alcohol use and the feasibility of self-help programs. Focus group findings guided the development and implementation of the self-help groups. A post- intervention focus group was held to determine the effectiveness and community-wide effect of the self-help programs. Findings: Focus group participants agreed that alcohol consumption was a problem in Saint Vincent, leading to underage drinking and violence. Suggestions to encourage self-help meeting attendance included organizing group activities and providing visuals to illustrate alcohol’s effects on health. Self-help group members were surveyed about their group experience. Of the 35 members surveyed, 77% said the group was very helpful, and 91% indicated that they would attend again. -

Global Mental Health

global mental health ETIOLOGY REVIEW Prevalence and correlates of alcohol use in a central Nepal district: secondary analysis of a population- based cross-sectional study S. D. Rathod1, N. P. Luitel2* and M. J. D. Jordans3,4 1 Department of Population Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK 2 Research Department, Transcultural Psychosocial Organization Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal 3 Centre for Global Mental Health, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, King’s College London, London, UK 4 Research and Development Department, HealthNet TPO Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Global Mental Health (2018), 5, e37, page 1 of 11. doi:10.1017/gmh.2018.28 Background. As reported from studies conducted in Nepal, between 15% and 57% of adults had ever consumed alcohol and between 1.5% and 25% of adults have alcohol use disorders (AUD). Few studies in Nepal have identified the corre- lates of consumption or described the help-seeking patterns and stigma among those affected with AUD. Methods. Interviewers administered the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) as part of population- based surveys of adults in Chitwan District between 2013 and 2017. We conducted a secondary analysis to identify socio- demographic and health-related correlates of recent alcohol consumption using the χ2 test, to identify correlates of total AUDIT scores among men who drink using negative binomial regression, and to describe the treatment-seeking and stigma beliefs of men with AUD. Results. Over half (53.7%, 95% CI 50.4–57.0) of men (n = 1130) recently consumed alcohol, and there were associations between being a drinker with age, religion, caste, education, occupation and tobacco use. -

Input to WHO Global Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020 Zero Draft 10 October 2012

Input to WHO Global Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020 Zero Draft 10 October 2012 Summary: 1. Alzheimer’s disease and dementia are a target action area for WHO and Member States. 2. There is a lack of awareness about Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias worldwide. 3. Stigma is a barrier to find solutions. 4. Like with other mental and neurological disorders, there is a huge treatment gap for dementia. We estimate that in high income countries 20-50% of people with dementia are diagnosed, in lower and middle-income countries only 10%. 5. There are practical actions that are ready for adoption now to support persons with dementia and their families, including some validated in lower and middle income countries. 2 i) Introduction and Reference Points Dementia as a major NCD was recognised in the UN High Level Political Declaration on NCD’s, in September 2011. And further noting resolution EB130.R6 “Noting that the Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting of the United Nations General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases recognizes that mental and neurological disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease, are an important cause of morbidity and contribute to the global burden of noncommunicable diseases, and therefore it is necessary to provide equitable access to effective health programmes and interventions including for the whole population, from an early age; Recognizing the importance of gender-based approaches, solidarity and mutual support for social development, of the realization of the human -

Grand Challenges in Global Mental Health

COMMENT NANOTECHNOLOGY Materials SUMMER BOOKS Reviewers CONSERVATION Concern EQUALITY Action needed to should not be regulated on and editors suggest about alien species is stop science prizes going size alone p.31 reading for your holiday p.32 scientific and practical p.36 primarily to men p.37 chizophrenia, depression, epilepsy, dementia, alcohol dependence and other mental, neurological and sub- Sstance-use (MNS) disorders constitute 13% of the global burden of disease (Table 1), surpassing both cardiovascular disease and cancer1. Depression is the third leading contributor to the global disease burden, and alcohol and illicit drug use account for more than 5% (ref. 2). Every seven seconds, someone develops dementia3, costing the world up to US$609 billion in 2009 (ref. 4). H. TIMMERMANS/GLOBAL INITIATIVE ON PSYCHIATRY INITIATIVE H. TIMMERMANS/GLOBAL By 2020, an estimated 1.5 million people will die each year by suicide, and between 15 and 30 million will make the attempt5. The absence of cures, and the dearth of preventive interventions for MNS disor- ders, in part reflects a limited understanding of the brain and its molecular and cellular mechanisms. Where there are effective treat- ments, they are frequently not available to those in greatest need. In 83% of low-income countries, there are no anti-Parkinsonian treatments in primary care; in 25% there are no anti-epileptic drugs6. Unequal distri- bution of human resources — between and within countries — further weakens access: the World Health Organization’s European region has 200 times as many psychiatrists as in Africa7. Across all countries, investment in fundamental research into preventing and treating MNS disorders is disproportionately low relative to the disease burden8. -

Globalising Mental Health Or Pathologising the Global South? Mapping the Ethics, Theory and Practice of Global Mental Health

Disability and the Global South, 2014 OPEN ACCESS Vol.1, No. 2, 188-202 ISSN 2050-7364 www.dgsjournal.org Globalising Mental Health or Pathologising the Global South? Mapping the Ethics, Theory and Practice of Global Mental Health China Millsa* and Suman Fernandob aDepartment of Education, University of Sheffield, UK; bFaculty of Social Science and Humanities, London Metropolitan University, UK. Corresponding Author – Email: [email protected] Embodied in the very concept of Global Mental Health (an area that is emerging as both a field of study and a global movement), mental health is conceptualised as being ‘global’; mental disorders are constructed as having ‘a physical basis in the brain….they can affect everyone, everywhere’ and are understood to be ‘truly universal’ (WHO, 2001a:x, 22). The construction of ‘mental disorder’ as universal is used to draw attention to inequalities in access to mental health care and treatment globally – the ‘treatment gap’ - and to push to scale up mental health services in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) based on those in high-income countries (HICs). This push arises from two separate, yet interrelated, arenas; the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Movement for Global Mental Health (MGMH) (www.globalmentalhealth.org). Such a view - reducing complex matters of living, behaving and thinking to ‘mental’ health and disorder developed in a particular socio-cultural context - is strongly contested by groups of service users and survivors of psychiatry, or those who identify as psychosocially disabled, in the global North and South; by academics and professionals in the field of transcultural psychiatry; and by members of the Critical Psychiatry Network (CPN) (http://www.criticalpsychiatry.net/) (see Fernando, 2014; and Mills, 2014). -

Mental Health Atlas 2014 Provides Up-To-Date Information on the State of Mental Health Services and Systems in Countries Across the World

WHO’s Mental Health Atlas series has already established itself as the single most comprehensive and most widely used source of information on the global mental health situation. WHO’s mental health Atlas 2014 provides up-to-date information on the state of mental health services and systems in countries across the world. It covers critical areas of mental health system development, including governance and financing, human resources, service availability and delivery, promotion and prevention, and surveillance. These data serve as a baseline for targets agreed by 194 member states of WHO in the Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020. MENTAL HEALTH ATLAS For more information, please contact: Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse World Health Organization Avenue Appia 20 CH-1211 Geneva 27 Switzerland Email: [email protected] http://www.who.int/mental_health/ evidence/atlasmnh/ ISBN 978 92 4 156501 1 MENTAL HEALTH ATLAS 2014 MENTAL HEALTH ATLAS 2014 WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data: The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion Mental health atlas 2014. whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area 1.Mental Health Services - statistics. 2.Mental Health Services - or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers atlases. 3.Health Policy - trends. 4.Health Personnel - statistics. or boundaries. Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent 5.Global Health. I.World Health Organization. approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. ISBN 978 92 4 156501 1 (NLM classification: WM 17) The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended © World Health Organization 2015 by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

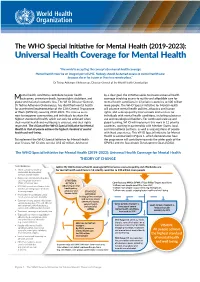

(2019-2023): Universal Health Coverage for Mental Health

The WHO Special Initiative for Mental Health (2019-2023): Universal Health Coverage for Mental Health “The world is accepting the concept of universal health coverage. Mental health must be an integral part of UHC. Nobody should be denied access to mental health care because she or he is poor or lives in a remote place.” Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the World Health Organization ental health conditions contribute to poor health by a clear goal, the initiative seeks to ensure universal health Moutcomes, premature death, human rights violations, and coverage involving access to quality and affordable care for global and national economic loss. The WHO Director-General, mental health conditions in 12 priority countries to 100 million Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has identified mental health more people. The WHO Special Initiative for Mental Health for accelerated implementation of the 13th General Programme will advance mental health policies, advocacy and human of Work (GPW13), covering 2019-2023. The time to act is rights, and scale up quality interventions and services for now to empower communities and individuals to attain the individuals with mental health conditions, including substance highest standard of health, which can only be achieved when use and neurological disorders. For continued scale up and their mental health and well-being is ensured, and their rights global learning, WHO will implement this work in 12 priority respected. The vision of the WHO Special Initiative for Mental countries, working in partnership with Member States, local, Health is that all people achieve the highest standard of mental and international partners, as well as organizations of people health and well-being. -

“Investing in Mental Health”

Investing in MENTAL HEALTH This publication was produced by the Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence, Noncommunicable Diseases and Mental Health, World Health Organization, Geneva. For further information and feedback, please contact: Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence, Avenue Appia 20, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 791 21 11, fax: +41 22 791 41 60, e-mail: [email protected], website: www.who.int/mental_health WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data World Health Organization. Investing in mental health. 1.Mental disorders - economics 2.Mental disorders - therapy 3.Mental health services - economics 4.Mental health services - economics 5.Cost of illness 6.Investments I.Title. ISBN 92 4 156257 9 (NLM classification: WM 30) © World Health Organization 2003 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from Marketing and Dissemination, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel: +41 22 791 2476; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to Publications, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; email: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatso- ever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement.